Resource and Study Guide

advertisement

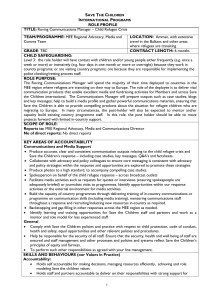

Resource and Study Guide The Play and its Context • Introduction The Suppliants p. 2 The Suppliants p. 5 Reinvented • Plot Summary p. 7 • Character Profiles p. 9 • The Playwright p.14 • Production History p.18 In the Classroom • Using the Guide p.19 • Theatre and Acting Classes p.20 • English Classes p.20 About this Production Big Love contains adult themes and language. • Who’s Who p.21 • From the Director p.23 • Scenic Design p. 25 • Costume Design p. 26 • Pre and Post Show p.27 Questions and Activities 2 Introduction Ancient Influences: The Suppliant Women Big Love is inspired, in part byThe Suppliant Women or The Suppliants. Written in approximately 492 BC by Aeschylus the play is considered to be the first extant drama in Western European literature. It is the first part of a tragic trilogy, the second and third plays are lost. The action of the play revolves around the rejection by the 50 daughters of Danaus to proposals of marriage proffered by the 50 sons of Danaus’ brother, Aegyptus. The sisters flee to the island of Argos to seek protection 3 of the gods and the king, Pelasgus. The fifty girls supplicate their distant relation, Pelasgus, who vows to defend the girls. (Their threat of mass suicide at the holy altar, an appalling act of defamation helps him to see the light.) The sons of Aegyptus threaten war against Argos and are rebuffed by Pelasgus and The Suppliant Women ends in a tense standoff. From a reconstruction of available sources, Aeschylus’ two other plays in the trilogy were most likely titled The Egyptians and The Daughters of Danaus. In The Egyptians Pelasgus is defeated by the brothers and Danaus assumes the throne. Danaus agrees to allow his daughters to be married to the conquerors. However, he secretly commands them to kill their husbands on their wedding night. All obey except one; Hypermnestra saves her husband, Lynceus because she is truly in love with him. In part three of the trilogy, The Daughter of Danaus or The Danaids the moral, legal, and political fallout of Hypermnestra’s actions are the focus. She is put on trial for breaking her oath and the goddess of love, Aphrodite defends her and eventually acquits her by pointing out the universal power of love and sex and the courage of Hypermnestra to stand up against her sisters and follow her heart. The desire for peace, marriage, and procreation is restored at the end of this trilogy, with the underlying 4 theme of female terror of male aggression still reverberating. Production of The Suppliants at the Epidaurus Theatre, Greece, 1994 5 Charles Mee Shatters The Suppliant Women Big Love at the University of Florida (2004) In her article about her father’s work, “Shattered and Fucked up and Full of Wreckage” Erin Mee describes Mee’s plays as “blueprints for events. For spectacles. For festivals.” (83). Mee frequently begins with a familiar story, often from Greek classic tragedies. As Mee himself states, “There is no such thing as an original play.” (www.charlesmee.org) He provides evidence ranging from the Greek playwrights (whose plots were taken from earlier poems and myths) to Shakespeare who liberally borrowed and often took verbatim from many sources including the Greeks in many of his plays. While The Suppliants provide the framework 6 for the action of Big Love, it is barely recognizable when compared side by side to the source material. Mee uses the Greeks as a launching point and pastes together plays like a collage with multiple sources from popular culture. He is the ultimate American postmodern or “anti-modern” playwright. The vestiges of Greek classic drama are evident in the songs, dances, and movement pieces that are integrated into Big Love, Mee’s ode to the Greek parodos, the songs and dances that the chorus performed in classic Greek performances. Big Love is a comedy about rape (Cummings, 78) that manages to juxtapose wild, wacky humor and violent, bitter pathos side-by-side to create a world with its own set of laws. Mee takes the setting of The Suppliants from Argos to present day Italy. Danaus, the father of the fifty sisters is not seen in the play. The sisters are on their own and even the father substitute in the character of Piero, whom they ask for assistance, eventually sells them out to the fifty cousins. The cousins are Greek-American and Aphrodite, the judge is replaced by a wise Italian “mama.” The action of the play mirrors the action of the trilogy and ends with Bella, the classic Italian mama finding Lydia (Hypermnestra) not guilty and declaring that “Love trumps all.” Mee keeps the framework of the trilogy by Aeschylus while creating an 7 original, outlandish play that reinvents this classic tragedy into a post-modern tragic-comedy. Plot Summary Big Love is set on the coast of present day Italy. The action begins with the arrival at an Italian villa of eight of fifty Greek sisters who have fled (by yacht) their wedding ceremony to their Greek-American cousins. The sisters meet Piero, the wealthy owner of the villa and supplicate themselves to him asking for asylum. They claim international refugee status and seek Piero’s protection 8 Production of Big Love from their arranged marriages to their cousins. The brothers eventually pursue them to Piero’s villa via helicopter. While one brother, Nikos is truly puzzled by his betrothed, Lydia’s flight, another is outraged. Constantine is ready to take what is his, as he states, “I’ll have my bride. If I have to have her arms tied behind her back and dragged to me. I’ll have her back.” With the arrival of the brothers and Piero’s compliance to their demand to be married immediately, the girls decide to take action. All of the sisters make a pact to murder their husbands on their wedding night. With that knowledge the girls prepare for the wedding with the help of some houseguests of Piero as well as his feckless nephew, Giuliano, who longs for his own wedding and bedecks himself in hopes of being able to participate in the day’s big event. Wedding gifts arrive and a cake is ordered as the tension escalates. With the marriage ceremony completed, the celebration begins with toasts and a first dance. During this the grooms are all murdered except for Nikos, Lydia’s husband. The couple is discovered by the sisters and Lydia is put on trial for “treason.” Bella acts as judge and after hearing both sides of the story, she acquits Lydia. The celebration continues and the sisters bid farewell to Lydia and Nikos, 9 who depart to an uncertain future, leaving the sisters face their own future alone. Character Profiles Ferdinand Hodler The Sisters Lydia - A young woman in her 20’s who is unsure of her relationship with Nikos, the man her father has arranged for her to marry. Although suspicious of the situation, she lets her heart guide her. 10 “Sometimes people don’t want to fall in love. Because when you love someone it's too late to set conditions.” Thyona - An unhappy, angry, man-hating young woman who leads her sisters in revolting against their arranged marriages. “Men. You think you can do whatever you want with me, think again. you think that I’m so delicate? you think you have to care for me? You throw me to the ground you think I break? you think I can’t get up again?” Olympia – Lydia and Thyona’s younger sister, a self absorbed, materialistic young woman who is more concerned about designer wedding gowns than about the man she is marrying. “Nothing seems to be working out I don’t see why at least on my wedding day I can’t have things exactly the way I want them!” Chloe, Neysa, Thea, Adara, Penelope 11 The Brothers Nikos – In love with Lydia, a talkative, sensitive man who is reasonable and although confused, just wants to do the right thing. “And I think sometimes I scare people because of it they think I’m so, like determined just barging ahead – not really a sensitive person, whereas, in truth, I am.” Constantine – the oldest brother, a male chauvinist who asserts his power through aggression and violence, engaged to Thyona. “there’s no such thing as good guys and bad guys only guys and they kill people” Oed - the quiet brother who passively goes along with the others but holds back his feelings of rage, engaged to Olympia. “they know the pain, they don’t want to talk about it” 12 Lex, Paris, Ajax, Pavlos, Dion The Hosts Giuliani - Piero’s gay nephew who sympathizes with the plight of the sisters and attempts to help them out. “And I’ve often thought, oh, well, maybe he really did love me maybe that was my chance and I ran away from it because I didn’t know it at the time.” Piero – the benevolent yet self-seeking Italian mama’s boy. He is coerced into dealing with the unpleasant situation forced upon him by the sisters but manages to resolve the issues with a craftiness and . . . a glass of chianti. “In the world I come from it's not always all or nothing. Men learn to compromise all the time. After all we have to go on living in the same world together.” Bella – Mother of Piero, her oldest son out of 13 boys and her favorite. A wise old woman who knows about “big love.” 13 “This is why: love trumps all. Love is the highest law.” The Guests Eleanor – an English woman who delights in the prospect of a big wedding. “Do we have a real happiness in being together, talking, or just doing nothing together? Do we have a feeling of paired unity?” Leo – Eleanor’s paramour, a slightly used Italian gigolo who is intoxicated with life’s pleasures as well as too many martinis. “When you are young, you think nothing of it. But the older you get the more you think: oh, god, let me have more pleasures!” The Playwright Charles L. Mee (b. 1938 in Evanston, IL) The defining moment of Charles Mee’s life came at the age of fourteen, when what he had described as a vibrant youth was interrupted by a case of polio in the summer of 1953 that would leave him disabled for the rest of his life. During one of his long stays in the hospital, Mee was given a copy of Plato's Symposium, an experience he identifies as a turning point in his 14 Mee on writing a play: “I like plays that are not too neat, too finished, too presentable. My own plays are broken, jagged, filled with sharp edges, filled with things that take sudden turns, careen into each other, smash up, veer off in sickening turns. That feels good to me. It feels like my life. And then I like to put this chaotic stuff – with some struggle remaining – into a classic form, a Greek form, or a beautiful dance theatre piece, or some other effort at civilization.” (from A Nearly Life, 214)A A chapter from Normal Mee’s biography Nearly Normal Life. http://www.twbookmark.com/book s/91/0316558362/chapter_excerpt9 373.html ` 15 Notes on a Manifesto by Charles L. Mee If Aristotle was right that human beings are social animals that we create ourselves in our relationships to others, and if theatre is the art form that deals above all others in human relationships, then theatre is the art form, par excellence, in which we discover what it is to be human and what it is possible for humans to be. Whatever else it may do, a play embodies a playwright's beliefs about how it is to be alive today, and what it is to be a human being so that what a play is about, what people say and how things look onstage, and, even more deeply than that, how a play is structured, contain a vision of what it is to have a life on earth. If things happen suddenly and inexplicably, it's because a playwright believes that's how life is. if things unfold gradually and logically, that's an idea about how the world works. if characters are motivated by psychological impulses that were planted early in a character's life in her childhood home, it's because a playwright believes that's what causes people to do things they do the way they do them. Or, if a character is motivated by other things, in addition, or even primarily motivated by other things by the cumulative impact of culture and history, by politics and economics, by gender and genetics and rational thought and whim, informed by books and by the National Enquirer, given to responses that are tragic and hilarious, conscious and unconscious, ignorant and informed at the same time it's because the playwright believes this complex of things is what makes human history happen. Most of the plays I grew up seeing didn't feel like my life. They were such well-made things, so nicely crafted, so perfectly functioning in their plots and actions and endings, 16 so clear and clearly understood, so rational in their structures, in their psychological explanations of the causes of things. And my life hadn't been like that. When I had polio as a boy, my life changed in an instant and forever. my life was not shaped by Freudian psychology; it was shaped by a virus. and it was no longer well made. it seemed far more complex a project than any of the plays I was seeing. And so, in my own work, I've stepped somewhat outside the traditions of American theatre in which I grew up to find a kind of dramaturgy that feels like my life. And I've been inspired a lot by the Greeks. I love the Greeks because their plays so often begin with matricide and fratricide, with a man murdering his nephews and serving the boys to their father for dinner. That is to say, the Greeks take no easy problems, no little misunderstanding that is going to be resolved before the final commercial break at the top of the hour, no tragedy that will be resolved with good will, acceptance of a childhood hurt, and a little bit of healing. They take deep anguish and hatred and disability and rage and homicidal mania and confusion and aspiration and a longing for the purest beauty and they say: Here is not an easy problem; take all this and make a civilization of it. And the forms in which they cast their theatre were not simple. Unlike Western theatre since Ibsen, which has been essentially a theatre of staged texts, the Greeks employed spectacle, music, and dance or physical movement, into which text was placed as one of the elements of theatre. The complexity and richness of form reflected a complexity and richness of understanding of human character and human history. 17 The Greeks and Shakespeare and Brecht understood human character within a rich context of history and culture. This is my model. In 1906/07, Picasso stumbled upon cubism as a possible form. Immediately, he made three pencil sketches of a man, of a newspaper and a couple of other items on a table, and of Sacre Coeur that is, of the three classic subjects of art: portraiture, still life, and landscape. And he proved, to his satisfaction, therefore, that cubism "worked." My ambition is to do the same for a new form of theatre, composed of music and movements as well as text like the theatre of the Greeks and of American musical comedy and of Shakespeare and Brecht and of Anne Bogart and Robert Woodruff and of Robert Le Page and Simon McBurney and of Sasha Waltz and Jan Lauwers and Alain Platel and of Pina Bausch and Ivo van Hove and of others working in Europe today and of the theatre traditions in most of the world forever. -Charles L. Mee, 2002 18 Production History Big Love premiered at the Humana Festival of New American Plays at the Actors' Theatre of Louisville in 2000 (photo above) directed by Les Waters, and, in 2001, at the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven, CT, Berkeley Rep in California, the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, and the Next Wave Festival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. 2001. Big Love directed by Brian Kulick and produced at ACT in Seattle and by Darron West and produced by the Rude Mechanicals in Austin, Texas. 2001. Big Love directed by Betty Bernhard at the University of Calicut, School of Drama, India. In Malayalam. 2002. Big Love directed by Howard Shalwitz at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Washington, DC and directed by Mel Shapiro for Pacific Resident Theatre, Venice, CA and directed by Meg Gibson at the Salt Lake Acting Company, Salt Lake City, Utah. 2003. Big Love directed by Richard Hamburger at the Dallas Theatre Center, directed by Jiri Zizka at the Wilma Theatre, Philadelphia, PA, directed by Sarah Jane Hardy at Theatre Vertigo, Portland, OR. 2004. Big Love directed by Jeff Griffin at Early Stages, New York. 2005. Big Love directed by Mo Ryan and Jeanine Thompson at the Red Herring Theatre Ensemble, Colombus, OH and directed by Michael Fields at the Redwood Curtain, Eureka, CA. 19 In the Classroom Using the Guide This guide will help classroom teachers at both the high school and college levels. The information is useful for university theatre classes including acting, introduction to theatre, history of the theatre, playwrighting and script analysis. For teachers of high school theatre and English classes information is included that introduces or integrates the experience of the production into class content. Below is a list of sources that may be useful to you and were used in preparing this study guide. Complete text for Big Love and other plays by Charles Mee http://www.charlesmee.org./html/big_love.htm Bogart, Anne and Tina Landau. The Viewpoints Book. New York: TCG, 2005. Cummings, Scott. Remaking American Theatre: Charles Mee, Anne Bogart and the SITI Company. New York: Cambridge UP, 2006. 20 Dixon, Michael Bigelow and Joel A. Smith, eds. Anne Bogart: Viewpoints. Lyme: Smith and Kraus, 1995. Mee, Charles L. A Nearly Normal Life. New York: Little, Brown, 1999. Mee, Charles L. History Plays. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1998. Oates, Whitney J. and Eugene O’Neill, Jr., eds. The Complete Greek Drama. New York: Random, 1938. English and Theatre Classes For the high school and university acting class Big Love and Charles Mee’s other plays are excellent sources for monologues for audition and class work. Go to http://www.charlesmee.org./html/plays.html for complete texts of all of his plays. While he often applies a poetic structure, his language is modern and the characters complex. For English classes there are a variety of questions and activities at the end of the guide to explore and compare Mee’s source material Aeschylus’ The Suppliants to Big Love. 21 Who’s Who in BIG LOVE Lydia played by Cecily Ryan Thyona played by Sarah Adams Olympia played by Lizzie O’Hara Piero played by Jay Baglia Giuliano played by Josh Jack Carl Bella played by Amy Lizardo Nikos played by Omar Munoz Constantine played by Josh Marx Oed played by Chris Gaorian Eleanor played by Monique Warren Leo played by Wesley Hofman Penelope played by Christina Rodriquz Neysa played by Caitlin Dissinger 22 Adara played by Sarah Luna Chloe played by Joey Sandin Thea played by Kat Tan Lex played by Chris Carter Dion played by Havish Ravipati Paris played by Philip Nguyen Pavlos played by Sean Gilvary Ajax played by Eric Medeiros 23 Director’s Notes I don’t know when I first heard about playwright Charles Mee but I was intrigued with his radical notion of allowing anyone to rewrite or remake his plays. I visited his web site and there for the taking were full text versions of his plays, available to download FOR FREE! But then I started to read his plays and the above became a footnote to this story. His writing and approach to theatre was revolutionary and thrilling to me. It also helped that he had a close professional relationship to, for me, one of the most daring and imaginative directors in American theatre today, Anne Bogart. His was a voice from a world that I desired to create on stage. The intriguing use of music, language, and movement in Big Love results in a giddy yet solemn, hilarious yet shocking, cerebral yet poignant play that defies categories and slashes through audience expectations. I wondered what life experiences had informed this unique playwright and his work. I read his autobiography, A Nearly Normal Life and only then did his plays seem to make perfect sense. An athletic, vital teenager Mee was changed forever by a bout of polio in the summer of 1953. More than 50 years later Mee still struggles with both selves in one body: the intact 14 year old football player and the almost 70 year old disabled man, he writes, “For myself, to this day I have 24 never had a dream in which I walked with crutches; I’ve never had a dream in which I was disabled in any way; in my dreams my body is intact as it was when I was fourteen.” In his plays he brings his shattered physical existence to deconstruct classic Greek texts because it simply feels right to him, “ The Greeks took no easy problems. They put on the stage a world of unspeakable anguish, of matricide and fratricide and patricide, and then they refused to blink. They looked into the abyss of human life and human nature with open eyes and understood that the thing to do is to feel life as it is, in all its anguish as well as its aspirations, its missed opportunities and its savored beauties, never to falsify it, never to pretty it up; but rather to look at it bravely, unflinchingly.” (215) He knows what looking into the abyss is and Mee’s work takes a reckless yet unflinching look at the world, often through the lens of the Greeks and bewildered yet enthralled we, his audience are transported. Big Love is classic Mee, a riotous world of extremes and startling twists and turns that at the core is a diatribe on marriage and relationships between men and women but also about those achingly stunning moments in human existence that are not often seen on stage. In his work Mee often revisits the topic of marriage (perhaps having been married three times.) However, this is hardly a tragedy but rather a full-blown, what I term “violent comedy,” a new dramatic genre. The “well-crafted” dramatic structure is dismantled and in its place is a play that becomes a vehicle 25 for Mee’s own experience of life, loss, and love through a variety of performance forms, an ode to the ancients and yet extraordinarily modern, youthful, and physical. As a director Mee requires that you be a collaborator in the creation of the performance, a co-conspirator if you will. As Erin Mee, the playwright’s daughter and a director herself states, “He sets up a situation that requires the director, in turn, to elaborate on what he has written. Therefore, as a director I can’t simply illustrate what my father has done; I have to meet the text with other elements – dance, music, painting. I’m not just allowed to bring my ideas to the production; I’m expected to do so.” Mee demands no adherence to the text but gives a director a blueprint to build a performance, a chance to work with abandon and to rip into his play creating a new play. To paraphrase Mee “that feels good to me.” Kathleen Normington March 2007 26 Scenic Design 27 Costume Design 28 Pre-Show Questions and Activities 1. Brainstorm a list of ideas, images, emotions, colors, objects, or experiences that the title of the play reveals? 2. Compare this passage from Aeschylus’ The Suppliants with this passage from Mee’s Big Love. What do the two scenes share? Can you identify the characters of the Chorus and the King from The Suppliants in the scene from Big Love? How does the Greek god, Zeus figure in both scenes? Compare the mood created by each playwright. Compare the idea of state in The Suppliants with family in Big Love. From The Suppliants Chorus: The King of Argos: Justice, the daughter of right-dealing Zeus, Justice, the queen of suppliants, look down, That this our plight no ill may loose Upon your town! This word, even from the young, let age and wisdom learn: If thou to suppliants show grace, Thou shalt not lack Heaven’s grace in turn, So long as virtue’s gifts on heavenly shrines have place. Not at my private hearth ye sit and sue; And if the city bear a common stain, Be it the common toil to cleanse the same: 29 Chorus: King of Argos: Chorus: King of Argos: Chorus: King of Argos: Therefore no pledge, no promise will I give, Ere counsel with the commonwealth be held. Nay, but the source of sway, the city’s self, art thou, A power unjudged! Thine, only thine, To rule the right of hearth and shrine! Before thy throne and scepter all men bow! Thou, in all causes lord, beware the curse divine! May that curse fall upon mine enemies! I cannot aid you without risk of scathe, Nor scorn your prayers – unmerciful it were. Perplexed, distraught I stand, and fear alike The twofold chance, to do or not to do. Have heed of him who looketh from on high, The guard of woeful mortals, whosoe’er Unto their fellows cry, And find no pity, find no justice there. Abiding in his wrath, the suppliants’ lord Doth smite, unmoved by cries, unbent by prayful word. But if Aegyptus’ children grasp you here, Claiming, their country’s right, to hold you theirs As next of kin, who dares to counter this? Plead ye your country’s laws, if plead ye may, That upon you they lay no lawful hand. Let me not fall, O nevermore, A prey into the young men’s hand; Rather than wed who I abhor, By pilot-stars I flee this land; O king, take justice to thy side, And with the righteous powers decide! Hard is the cause – make me not judge thereof Already I have vowed it, to do nought Save after counsel with my people ta’en, King thou I be; that ne’er in after time, If ill fate chance, my people then may say – In aid of strangers thou the State hast slain. From Big Love Lydia: Really we were mostly hoping to ask you to just: take us in. 30 Piero: Take you in? Lydia: Your nephew Giuliano says you have some connections. Piero: Oh? Lydia: And that you can help us. Piero: Well, of course, this is a country where people know one another and, Giuliano is right, sometimes these connections can be useful. If, for example, You were a member of my family, certainly I would just take you in. But (he shrugs) I don’t know you. Lydia: Piero: Oh. But. We are related. I mean, you know: in some way. Our people came from Greece to Sicily a long time ago and to Siracusa and from Siracusa to Taormina and to the Golfo di Saint’ Eufemia and from there up the coast of Italy to where we are now. So we are probably members of the same family you and I. Descended from Zeus, you mean. Olympia: Yes. We’re all sort of goddesses in a way. Thea: Yes, we are! Piero: Indeed. It’s very enticing to recover a family connection to Zeus. And, where is your father, meanwhile? Is he not able to take care of you? Our father signed a wedding contract to give us away. Lydia: 31 Piero: To your cousins from Greece. Thyona: From America. They went from Greece to America, and now they’re rich and they think they can come back and take whatever they want. And the courts in your county: they would enforce such a contract? Piero: Lydia: It’s an old contract. It seems they will. We have nothing against men – Olympia: Not all of us. Neysa: That’s right, Thyona. Lydia: But what these men have in mind is not usual. Thyona: Or else all too usual. [silence] Piero: Thyona: You know, as it happens, I have some houseguests here for the weekend and I would be delighted if you would all join us for dinner, stay the night if you like until you get your bearings but really as for the difficulties you find yourselves in disagreeable as they are and as much as I would like to help this is not my business. Olympia: Whose business is it if not yours? You’re a human being. And a relative. Piero: A relative? 32 Penelope: Thyona: A close relative. This is a crisis. Piero: And yet . . . You know, I am not the Red Cross. Thyona: And so? Piero: So, to be frank, I can’t take in every refugee who comes into my garden. Olympia: Why not? Piero: Because the next thing I know I would have a refugee camp Here in my house. I’d have a house full of Kosovars and Ibo and Tootsies boat people from China and godknows whatall. What do I know? I don’t know what sort of fellows they are. I should put myself, perhaps my life on the line – Knowing nothing – and also the life the life of my nephew my brother next door my brother’s sons. I put their lives on the line for what? 3. Read the Plot Description and decide on a potential sequence of actions. Working in groups give a title to each action and create a series of tableaux to illustrate each action. If you can, add music to each tableau to help illustrate and illuminate each action. Post Show Questions 33 1. What moments in the production were surprising? What were shocking? Why? Can you identify the reason that these moments were memorable? 2. Which character could you relate to in the play? Why was that particular character interesting to you? 3. Imagine and then discuss what happens to the characters after the play ends. Create Big Love: The Sequel. What happens to Olympia, Thyona, and the other sisters? Do they eventually get married? Do you think they return to Greece? 4. What will married life be like for Lydia and Nikos? Do you think they live “happily ever after?” What clues does the play/production provide to support your opinion? 5. Is the ending of Big Love one of hope or despair? What elements of the production help you decide this? 6. One of the play’s themes is the power struggle between the genders. How is this revealed in the play and are there some surprising points of view? 34 7. The classic Greek theatre used the convention of the parados which was the entering song and dance of the chorus. In the parados of The Suppliants the chorus of the fifty sisters enters the sacred grove near Argos and pray to Zeus for help in escaping from their lustful, violent cousins. How does Mee replicate that moment in Big Love? 8. The stasimon are the songs and dances that are interspersed with episodes or scenes in classic Greek drama. Identify how Mee uses this theatrical device in Big Love.