21 capital structure - Waikato Management School

advertisement

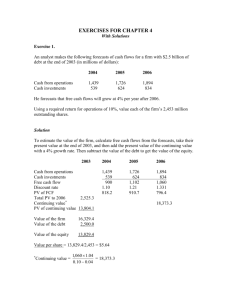

- . 21 CAPITAL STRUCTURE Introduction Capital Structure Research Modigliani-Miller - Proposition I M & M - Proposition II M & M and Taxes (M & M ‘Corrected’) Debt and Taxes Review of Miller and Modigliani Relaxing Other Assumptions Pecking Order Theory Creative Financial Instruments Debt is Better Summary Introduction The question of what is an ‘optimal’ capital structure for a firm continues to be at the core of research in the finance area. If there is a correct relationship between debt and equity then it would benefit a company to implement it. This chapter considers research in finance and reviews some research milestones. These landmarks indicate the direction of thinking in the area of capital structure. While there have been some consequential research conclusions, theories on capital structure are still evolving. The search for an ‘optimal’ capital structure must be seen within the context of that research, since what is ‘correct’ changes over time, changes between firms and can have different meaning for different people. Capital Structure Research Finance theories on the subject of capital structure have followed two broad approaches since they began in 1958. The initial work by Miller and Modigliani was a mathematical theory which they subsequently adapted to better reconcile it with the ‘real world’. With the focusing of attention on capital structure by Miller - . 424 Financial Management and Decision Making and Modigliani, further research followed. Much of this later work followed an alternative approach to research which was one of observing the finance world and drawing conclusions from what was happening. The approach of Miller and Modigliani was largely deductive, whereby particular predictions are made from theory. The second approach is essentially inductive and positivist whereby theory is derived from numbers of observations. In practice, research and knowledge gathering is a mixture of these two approaches, the emphasis shifting depending on the nature of the problem and the view of the researcher. Jensen, one of the later researchers, suggests that we are entering a new era of thinking on capital structure. Between Miller and Modigliani and Jensen, several important milestones have been passed. Pecking order theory, the introduction of new financial instruments and agency theory are a few of the more important developments. Modigliani-Miller - Proposition I The work of Miller and Modigliani resulted in the assertion that: “The market value of any firm is independent of its capital structure and is given by capitalizing its expected return at the rate appropriate to its [risk] class.” (Modigliani, F. & Miller, M.H., 1958, p. 268) This has become known as M & M Proposition I. They arrived at this conclusion by making several assumptions about the financial world and then mathematically proving that capital structure did not affect the value of the firm. Their assumptions (both implicit and explicit) were: - Capital markets are frictionless, i.e. there are no transaction costs. Individuals can lend and borrow at the same risk-free rate. There are no costs to bankruptcy. There are only two sources of finance for a firm, debt and equity. All firms are in the same risk class. There are no taxes (this assumption was later discarded). All cash flows are perpetuities, without growth. Corporate insiders have no more information about the firm than the outsiders. Managers always act to maximise shareholders wealth. While many of these assumptions may appear unrealistic they, and the resulting conclusion, set the direction for future developments in this area. An example may best show how M & M reached their conclusion. Example Two firms, A and B, are identical except for their capital structure. Both firms are the same size, both in the same line of business, and both generate the same revenue and operating profits. Firm A is financed totally by equity. Firm B, on the other - . Chapter 21: Capital Structure 425 hand, has 60% equity and 40% debt. If firm B is more valuable than firm A, then there must be value to their capital structure. If both firms have the same value, then their capital structure must be irrelevant. Assume that both firms have: - total assets of $200m, - revenue of $100m, - production and operating costs of $80m - the risk free interest rates is 10%. Their Income Statements would then be: ($m) Revenue Less production and operating costs Earnings before interest Interest on debt (Note: Firm B has debt of 40%, or $80 of $200) Net Income A 100 80 20 0 B 100 80 20 8 20 12 It would cost $200m to own all the assets of A and this investment would be entirely in equity. To own all of firm B, it would also cost a total of $200m but would take two different forms. Only $120m of the investment would be in the form of equity and $80m would be in the form of debt. If value is measured by the total cash coming out of the company into the hands of the owners, then it is necessary to see if both A and B generate the same cash to their owners. Firm A generates $20m. Firm B only pays out $12m to the owners from their operations. But being the owner of firm B means that not only is the equity owned, but so is the debt. Therefore, the owners of firm B also received the interest income of $8m, for a total income of $20m. If these income streams coming from firms A and B continue as perpetuities, it is clear that both A and B have the same value. This result seems so straightforward. Nevertheless, this simple result has some profound implications. Remember that one of the assumptions was that all individuals and corporations could lend or borrow at the same risk free rate. Assume that an investor, Sue, wants to invest in company A and she only has $12m. Sue knows that financial leverage (i.e. the existence of debt) increases the return on her investment if the firm is operating above the breakeven point. (See chapter on Leverage as Risk.) Sue is therefore unhappy about the capital structure of firm A. Sue could go to the bank on her own account and borrow money. She could add this borrowed money to her own money to make a total investment in company A. The result would be the same as if she had invested in just the equity of company B with her original equity. If she had used her $12m to hold equity in B, she would have owned 12/120, or 10% of the equity of B. This ownership would have entitled her to receive 10% of - . 426 Financial Management and Decision Making the Net Income, or $1.2m. On the other hand, to own 10% of firm A would require more than her $12m since the total equity of firm A is $200m. In fact, Sue would have to borrow $8m in order to own 10% of A. If she did, she would be entitled to 10% of the Net Income of A, $2m but she would then have to pay interest on her personal debt totalling $.8m ($8m borrowed times 10% interest), leaving her with $1.2m in net income. Thus, the investor creates her own financial leverage, she does not need the company to do it for her. Likewise, if Sue wanted to invest in company B, but would rather not have any financial leverage, she could undo the leverage by lending some of her money at the risk free rate. This ability of the individual to create or undo financial leverage implies that any capital structure that a firm may choose can be adjusted by the investors themselves. If investors can pick their own preferred capital structure, why should a firm believe it can increase investor wealth by settling on any one particular debt to equity ratio? Given the assumptions of M & M, the capital structure of a firm does not matter. M & M - Proposition II Proposition I focused on the value of the firm. Proposition II focuses on the expected return on equity of a company with various capital structures. M & M’s Proposition II is that the expected return on equity increases linearly as the amount of debt increases - provided that the debt remains risk free. But if increased debt levels increase the cost of debt, this also causes the rate of increase in the expected return on equity to decline. This is shown in Exhibit 21.1. Exhibit 21.1 Expected Rate of Return Expected Return on Equity (including changes to the expected return on equity due to changes in the expected return on debt) Return on Assets Expected Return on Debt Risk Free Debt Risky Debt Amount of Debt - . Chapter 21: Capital Structure 427 Since the sum of the returns to debt and equity must equal the total return generated by the assets of a company, it is possible to write the return on assets as follows: E(ra) = E(rd) x (% of Debt) + E(re) x (% of Equity) where E(ra) is the expected return on assets E(rd) is the expected return on debt E(re) is the expected return on equity Note: E(ra) is the cost of capital for the company (see Chapter 17) Rewritten, this equation becomes: E(ra) = [E(rd) ( D / (D+ E))] + [E(re) ( E / (D+ E))] and solving this equation for E(re): E(re) = E(ra) + D / E ( E(ra) - E(rd) ) Thus, proposition II shows mathematically that the expected return on equity increases as the amount of financial leverage increases, unless the expected return on debt rises. This rise in the expected return on debt will only happen when the debt holders feel they have lent more than can be justified at the risk free rate. The implications of this proposition affect the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) (see chapter on Cost of Capital). If the return on equity rises as the amount of debt rises, then it is in the best interest of the equity holders to have a large amount of debt. From the point of view of the company, large amounts of debt reduce the WACC, another positive development. Thus, it may seem that considerable debt is better than less debt. However, traditionalists reviewing the working financial world argue that equity holders are not lacking in common sense. They note that equity holders will require a larger return on their equity investment when the cost of a company’s borrowing begins to exceed the risk-free rate. Equity holders know that there is more risk when the company has more financial leverage and they demand to be paid for this risk. Equity holders also require a higher return because companies who provide a service of creating high amounts of financial leverage (i.e. high debt/equity ratios) trade at a premium to their ‘true’market price. Thus, the theoretical world of M & M is adjusted by real world observations. It is clear that there is a point at which the cost of capital (weighted average cost of the debt and the equity) is lowest. That point is before equity holders and debt holders both start requiring additional return for the increased amount of debt carried by the company. This is shown in Exhibit 21.2. - . 428 Financial Management and Decision Making Exhibit 21.2 Rates of Return Re (traditional) Re (MM) Ra (MM) Ra (traditional) Rd Ramin D/E = Debt/Equity M & M and Taxes (M & M ‘Corrected’) When the assumption of no taxes in the original model is relaxed (and the other assumptions remain in place) M & M (1963) adjust their view of the ‘optimal’ capital structure. The existence of corporate taxes in the real world results in added value to the firm that has debt. This added value due to the existence of taxes is called a tax shield. Example Using the earlier example of firms A and B and introducing a corporate tax rate of 40%, the concept of a tax shield can be illustrated. Recall that firm A was totally equity financed and firm B had 40% debt. Starting with the Net Income figure as calculated earlier, this results in: ($m) Net Income (before tax) Less tax at 40% Profit after Tax A 20 8 12 B 12.0 4.8 7.2 A 12 0 12 B 7.2 8.0 15.2 and the total cash flow to the owners now becomes: ($m) Total return on equity Plus Interest income Total Cash to Owners Thus, the existence of taxes combined with the ability to reduce taxable income by the amount of interest expense results in increased cash flowing out of the company - . Chapter 21: Capital Structure 429 with more debt. This implies that having debt results in a higher value to the owners. Debt and Taxes In 1977, Miller looked more closely at the issue of taxes. He suggested that the important result is not solely how much money flows out of the company, but how much the owners retain after being taxed on cash received from the company. Example Assume that no tax is paid at the personal level on income received as a result of owning equity but that tax is paid on interest income at the same rate as company tax (40% in our example). Under these conditions, there is no difference between owning firm A or B as follows: ($m) Total Cash to Owners Less personal tax on interest income at 40% Total personal net income A 12 B 15.2 0 12 3.2 12.0 If the personal tax rate is higher than the corporate rate, it is clear that income at the personal level due to equity is more favourable than income from holding debt. On the other hand, if the personal tax rate is lower than the corporate rate, it would be better if personal income was derived by holding debt in lieu of equity. This further consideration of the tax issues involved in maximising shareholders’ wealth leads to an examination of the ‘clientele’effect. Some shareholders prefer a capital structure with more equity while others prefer one with more debt. The choice depends on the tax structure of the shareholders. It is also possible that owners will have to pay tax on their equity income, further complicating the analysis. Therefore, each individual investor will assess which particular capital structure best suits their needs making it impossible to formulate a general rule for an ‘optimal’ structure. (Dividend policy is also partially influenced by a clientele effect.) Review of Miller and Modigliani M & M set the direction for research in the area of capital structure. Their approach was a deductive one, having a range of assumptions about the world which permitted their mathematical analysis to reach a clear conclusion. Their conclusion was that capital structure did not affect the value of the firm, so it did not matter - any capital structure was as good as any other. - . 430 Financial Management and Decision Making One of the more important implications of their analysis was that any individual could create or undo financial leverage at a personal portfolio level. This was seen as added confirmation that the capital structure did not matter. After ther initial work, M & M relaxed one of their assumptions acknowledging that there are corporate taxes. Furthermore, they noted that in the world of tax, interest expense reduced taxable income, thus creating a tax shield. The tax shield increased the present value of the cash flowing out of the firm. At this point in their analysis, the conclusion was that it was better to have debt than to be all equity financed. When M & M looked at the return to the equity owners of the firm, they noticed that the return increased as the amount of debt increased, provided that the cost of debt remained at the risk free rate. This confirmed their view that the existence of debt in the capital structure of the firm was better for the equity holders. Miller then examined the personal wealth of the owners of the firm after they paid personal tax (keeping all other assumptions in place). If the owner’s tax rate was 0% on income from equity (i.e. net income from the company) and the same tax rate on interest income as the company tax rate, then the net cash flow to the owners would be the same regardless of the capital structure of the firm. In this case, Miller reasoned, the capital structure is irrelevant. However, owners of firms may well have tax rates different to that of the firm itself and thus Miller asserted that the ‘proper’ capital structure for a firm depended upon the tax rates being paid by the firm and by the owners. In other words, capital structure decisions must consider the client (owners). Some owners may prefer more debt in the corporation, others may prefer more equity. Therefore, each possible capital structure could attract a client (owner). Instead of saying that capital structure does not matter, Miller suggests that it does, but since there are so many owners with various tax rates and firms with various tax rates, most capital structures would attract a client(s). When M & M looked at the actual capital structures of the corporations in the market place, they found a wide range of debt/equity ratios. The concept of ‘irrelevance’ appeared to suit what was happening in the real world. When they corrected their model and suggested that debt created a tax shield and thus increased the value of a firm, they were suggesting, indirectly, that managers of firms with little debt were not serving their shareholders properly. Nevertheless, the large variance in debt to equity ratios did not change. In 1977 Miller returned to a theory of capital structure which could explain this wide range of debt/equity ratios that existed in the market place. Several studies have examined the value added to firms when they increase their leverage. On balance, there is only weak confirmation that increased debt increases value. (Copeland, T.E. & Weston, J.F., 1988 review many of these studies.) Relaxing Other Assumptions Each of the other assumptions of M & M’s original model have been examined by various studies. The existence of transaction costs (friction) and differences - . Chapter 21: Capital Structure 431 between the cost of lending or borrowing tend to make little difference to the analysis of capital structure. Relaxing the assumption that there are no costs associated with bankruptcy has resulted in considerable study. As a firm gathers too much debt, it becomes possible for the equity holders to profit at the expense of the debt holders. This has led the debt holders to put restrictions - including a maximum amount of debt permitted - into their loan agreements. Thus, there seems to be an upper limit to the amount of acceptable debt. The assumption that only debt and equity are available to finance firms is now being challenged by the creative marketing skills of the finance industry. Assuming that corporate insiders and outsiders have the same information is also now being challenged and a ‘pecking order’theory of capital structure has emerged. Jensen challenged the assumption that managers always maximize shareholders’ wealth. This conflict led to Jensen’s view that ‘agency theory’ must also be considered. This theory is leading to a new view of capital structure. Pecking Order Theory In 1984, Myers suggested another view of why firms have a particular capital structure. By examining what is happening in firms, a ‘pecking order’ of capital structure has been formulated. This theory suggests that a firm’s capital structure is more a by-product of the pecking order rather than a specifically targeted relationship between debt and equity. When firms need finance, they adhere to the following pecking order to get the money: 1. First they use internally generated funds, i.e. retained earnings. 2. They adjust their target dividend payout to accommodate their investment opportunity without causing sudden changes in the dividend flow. 3. If external finance is required, firms prefer (in order of preference): - debt - hybrids between debt and equity (such as convertible bonds) - equity as a last resort. This means that capital structure is only the result of the financing needs of a firm. If a company is profitable, it does not need to raise funds externally. If it has been profitable for a long time, it is probable that it will have a low debt/equity ratio. On the other hand, if a firm is growing fast and has exhausted all internal sources of finance, it will issue new debt before issuing new equity. Thus, it is likely to have higher financial leverage. This is a dynamic theory of capital structure and there is no attempt to establish and maintain a specific debt/equity ratio; rather, managers take the line of least resistance in raising funds. It is easier to use company money than to borrow - . 432 Financial Management and Decision Making money. It is easier to deal with a lender than to comply with all of the requirements of issuing new equity. Perhaps it is just a matter of avoiding the friction of transaction costs which leads managers to behave this way. Others suggest that this behaviour is because it makes management easier, requiring less of their time and energy to work down the pecking order than to maintain a specific capital structure. Support is growing for this theory. Creative Financial Instruments The clear line between debt and equity has been blurred with the use of innovative financial instruments. This blurring means that traditional classifications of either debt or equity are no longer as meaningful. Some of these instruments include: - Convertible Bonds: this is a combination of two securities, a straight debt issue and a right to convert this debt into shares of equity. - Call provisions on debt: this part of the debt contract permits the firm to redeem the debt prior to the maturity date. - Preferred Stock: these are typically voting shares carrying with them a coupon rate of payment on a face value. These instruments receive income as if they were debts of the firm, but their holders cannot force bankruptcy, and they have voting rights. - Lines of Credit: firms often arrange a line of credit from a bank (or a syndicate of banks) which permits them to use these funds as they are needed. This could put, for example, $1 billion of debt at the firm’s disposal, but it is only used if needed. These instruments along with the traditional off Balance Sheet items, for example, leases, interlocking holdings, and contingent liabilities, make the problem of establishing the actual capital structure of a firm extremely difficult. Debt is Better A period of significant change in the capital structure of many major firms began in the late 1980s. These changes have come on the back of large waves of mergers and acquisitions (M & As), leveraged buy outs (LBOs), and management buy outs (MBOs). These changes in ownership of firms have, for the most part, been paid for with borrowed money. This borrowed money has then ended up on the balance sheets of the firm. Debt/asset ratios have risen as high as 85% (from a previous average of about 50%). With the extremely high levels of financial leverage the financial risk of running these firms has also increased. Kaplan documents many of these changes. He studied all public company buyouts with a minimum purchase price of $US50m in - . Chapter 21: Capital Structure 433 the USA from 1979 to 1985. Not only do these firms add large amounts of debt, but they generate large profits for the ‘active investors’ that buy the companies. Kaplan found that the salaries of the LBO business unit managers were 20 times more sensitive to performance than those in the typical public company. He also found that if the company is resold to the public again, total shareholder value increases 100% above the risk adjusted market returns over the same period. These large profits in the hands of the few LBO (and MBO) managers and owners have generated a lot of publicity. Not surprisingly, there is jealousy among those not making the profits, and resentment among those managers losing their jobs. Much of the criticism centres on the high debt levels remaining in the firm. The critics argue that so much debt in so many companies could lead to the collapse of several companies if a recession should occur since a recession would reduce the cash flow necessary to service the high amounts of debt. If it were not for the tax deductibility of interest expense, these buyouts would not be using so much debt and, the critics maintain, such large amounts of debt can only be bad because of all the risks associated with debt. Jensen sees this evolution toward high debt levels as the beginning of the end of the public corporation as we know it. This development, he asserts, is a good thing. Some of the reasons for positively viewing this move to extremely high debt levels include: 1. More tax is paid to the government through these transactions, not less. 2. Increased borrowing forces the management of the company to part with the cash it generates via interest expense payments. 3. Large amounts of debt will force a company to restructure itself as soon as problems develop, not permit the company to squander its wealth while remaining in a poor business situation. 4. The market place is better than the management of any company at allocating capital among competing businesses and then monitoring performance. 5. Debt forces managers to disgorge cash rather than waste or hoard it. Interest on debt is more reliable as a cash flow than dividend payments. Jensen is essentially questioning the final assumption of M & M. His ‘agency theory’ suggests that management does not work for the best interests of the shareholders, but is more interested in protecting management jobs and perks. The high debt levels forced upon companies by LBOs free up hoards of cash and permit the ‘active investors’to decide where that cash should then be invested. Therefore, Jensen believes that a new organisational form, which he calls an ‘LBO Association’ is a more efficient and effective form of business organisation and he views the change as being the most profound change to business organisation since World War II. - . 434 Financial Management and Decision Making Summary The search for a theory to explain the capital structure of businesses continues. It is one of the major focal points in the field of finance. By understanding the search for an ‘optimal’capital structure it is possible to understand part of the foundations of finance theory, the nature of financial research, and the current view on the evolutionary nature of businesses. Modigliani and Miller developed a model of capital structure based on deductive and mathematical reasoning and concluded that capital structure was irrelevant to the value of the business. Although higher levels of debt did affect the return on equity, they argued that this was due to the increased financial risk borne by the equity holders. Subsequent studies have looked at how businesses actually arrive at their capital structure and this has produced the ‘pecking order’ theory, that businesses take the path of least resistance in finding funds for investment. Thus, capital structure is a by-product of the historical and current profitability of the business. In addition, new creative financial instruments have made the actual process of defining a firm’s capital structure more and more difficult. The merger and buy-out activity of the 1980s has forced researchers to look closely at the final assumption made by Modigliani and Miller, that managers always act to maximise shareholder’s wealth. Kaplan and Jensen suggest that this it not so since there are insufficient incentives. Jensen believes that the market place solves this by taking publicly owned firms away from public ownership and running them as private ‘LBO Associations’. This process uses large amounts of debt implying that the market place considers the best capital structure to be a highly geared one. Several sound reasons for the use of debt led Jensen to assert that this dynamic change in the structure of public corporations is indeed good (i.e. better at maximising the wealth of the owners) and will therefore continue. We are witnessing a new phase in business structures and the search for the optimal capital structure continues. Glossary of Key Terms LBO (MBO) Leveraged buy out and management buy out refer to highly levered purchases of organisations. M & M Propositions Proposition I: That the value of any firm is independent of its capital structure and is given by capitalising its expected return at the appropriate rate for its risk class. Proposition II: That the expected return on equity increases linearly as the amount of debt increases provided that debt remains risk free. However, if the cost of debt increases, the rate of increase in the expected return on equity declines. - . Chapter 21: Capital Structure 435 M & M Corrected: That the existence of corporate taxes in the real world results in added value to the firm that has debt. Pecking Order An order of preference for finance from internally generated funds through to equity as a last resort. Selected Readings Copeland, T.E. & Weston J.F., Financial Theory and Corporate Policy, Addison-Wesley, 1988, pp 497-536. Jensen, M.C., Kaplan, R. & Stiglin, L., ‘Effects of LBOs on Tax Revenues of the U.S. Treasury’, Tax Notes, February 6, 1989 Jensen, M.C., ‘Eclipse of the Public Corporation’, Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct 1989, pp 61-74. Jensen, M.C. & Murphy, K.J., ‘Performance Pay and Top Management Incentives’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol 98 No 2, April 1990, pp 225-264. Kaplan, S., ‘Sources of Value in Management Buyouts’, as reported in ‘Eclipse of the Public Corporation’, Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct 1989, pp 61-74. Miller, M.H., ‘Debt and Taxes’, Journal of Finance, 32, May 1977, pp 261-276. Modigliani, F. & Miller M.H., ‘The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance, and the Theory of Investment’, American Economic Review, June 1958, pp 261-297. Modigliani, F. & Miller, M.H., ‘Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital’, American Economic Review, June 1963, pp 433-443. Myers, S.C., ‘The Capital Structure Puzzle’, Journal of Finance, July 1984, pp 575-592. Myers, S.C. & Majluf, N., ‘Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have Information That Investors Do Not Have’, Journal of Financial Economics, June 1984, pp 187-221. - . 436 Financial Management and Decision Making Questions 21.1 What effect does the personal tax rate have on the following? a. Net return to equity holders of a levered firm. b. Net return to debt holders of a levered firm. c. The value of the firm. 21.2 Company A and B are identical, except Company A is all equity financed and Company B has 30% debt and 70% equity. You have $100 of your own money to invest. Required: a. How can you invest in Company B to give you the same risk exposure as if you invest in Company A? b. How can you invest in Company A to give you the same risk exposure as if you invest in Company B? c. If the corporate tax rate is 30% and your personal tax rate is 20%, which firm best suits your needs? Why? d. If both the corporate and personal tax rates are 35%, which firm best suits your needs? Why? 21.3 What accounting difficulties would prevent you from really knowing the capital structure of a firm you may invest in? 21.4 ‘Creative Financial Marketing’affects corporate structure. How? 21.5 ‘Agency Theory’ explains the relationship between management and owners. development of agency theory as presented in this chapter. 21.6 How could high levels of debt: a. Increase corporate productivity? b. Force companies to release cash hordes? c. Hasten corporate restructuring? d. Increase shareholder wealth? e. Change the role of share markets? Discuss the