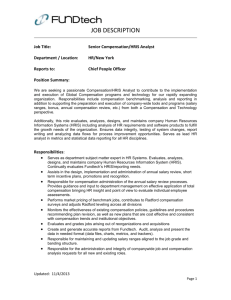

Human Resource Information Systems and the performance of the

advertisement