Raymond Burke 1 Factors in the Conquistadors Victory over the Inca

advertisement

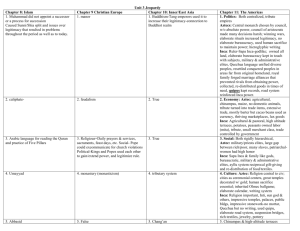

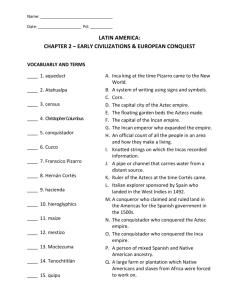

Raymond Burke 1 Factors in the Conquistadors Victory over the Inca It was a moment that defined history when Pizarro arrived on the coast of Peru in 1532. The Spanish Conquistadors, vastly outnumbered, won an astounding victory. But even with advanced weapons and horses, how could this have happened? The numerically superior Inca with their strategic fortresses and home advantage in rough, mountainous terrain should have been victorious. How did it all go wrong? Pizarro had 62 horsemen and 106 infantrymen. With shining armour, weapons such as cannons and arquebuses (a matchlock weapon), iron axes (iron not known in the Americas), trumpeters and horses, the Conquistadors had the upper hand in technological hardware. Shock factors also included the colour of the Spaniards’ white skin and that of their black slaves (Bernand 1988: 19 & 132). The arquebus, when fired, sounded like thunder which the Inca revered, and was demonstrated many a time to the Indians to scare them and to show off its ability to kill at distance (Innes 1969: 218). ‘For, after God, we owed the victory to the horses’. The importance of the horse has never been underestimated in the conquest of Peru. They were considered more important than slaves as indicated by the horses’ higher place on inventory lists (Cunningham-Graham 1949: 11 & 23). Along with steel armour and helmets, the Conquistador horsemen also wore the jack, a quilted, leather covered (sometimes iron-plated) coat (Quick 1973: 243), which provided light, flexible protection. Horses were also a psychological factor. The Inca thought that the Spanish were too weak to walk up the mountains so they rode horses. They did not expect an attack from such weakened men. But the Inca delay in attacking the Spanish while in the mountains allowed the Spanish to acclimatize to the precipitous conditions. The horses also had small bells attached to them to create more noise, panic and fear when they charged (Gheerbrant 1961: 329 & 342). On landing at Peru, Pizarro was able to secure the services of Indian informants, spies and auxiliaries for his force. He was informed of the Inca civil war and that the Inca Emperor, Atahualpa, the victor was camped only 350 miles away in Cajamarca, 12 days march away, up 9000 feet (Innes 1969: 232). The Inca, at their height, ruled over 8 million people, in a heterogeneous Empire, where people resented the harsh rule of the Inca (Bernand 1988: 21-2). These peoples welcomed the Spanish to free them from Atahualpa’s rule (Rostworowski de Diez Canseco 1999: 91 & 96). The Inca army probably had more than 200, 000 men armed with bow and arrows, clubs, spears and slings, protected by padded shirts, or strong tunics of cotton (Bernand 1988: 19 & 130), no match for the arquebuses. Some of the elite carried the flint or obsidian-bladed ‘macana’, a 2handed, hardwood sword, along with a long-handled battle-axe, a halberd like weapon with a sharp point on one end and a sharp blade on the other (Gheerbrant 1961: 186-7). This army could operate for months and range over hundreds of miles, though there were only a few elite, full-time, professional soldiers among the vast, unskilled commoner army (Kicza 1996: 345). The Inca had a support system consisting of roads, storehouses, and a chain of formidable fortresses and garrisons along the Andes with lightly loaded men and llama with provisions. By the time of the Conquest, the Inca had coordinated logistics, stores and supplies to protect themselves (D'Altroy 1992), but none of their weapons, sheer numbers or territorial advantages prevented the massacre to come. Raymond Burke 2 It has often been stated that the Inca Viracocha (the 8th Emperor) foresaw the coming of the Spaniards, but did not reveal this to the public for fear of causing panic. The Viracochas, as the later Spanish would be called, would be recognised by their beards (un-growable by the Indians) and by their long robes (Gheerbrant 1961: 132 & 147). But when Huayna Capac (the 12th Emperor) lay on his death-bed, he revealed the coming of the Spaniards, the return of the Viracochas (Gheerbrant 1961: 147), which is why Atahualpa ordered his men not to fight nor offend the Spanish. But the people did not fight against the Spanish so that the conquistadors could defeat the illegitimate heir and tyrant, Atahualpa (Gheerbrant 1961: 132 & 342). But as this story is related by the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, a half breed of noble descent, it is tainted by his Roman Catholic beliefs and his justification for the Spanish Conquest. Huayna Capac had created the new city of Quito (in modern Ecuador), and ruled with his favourite son, the illegitimate Atahualpa while giving Huascar, the rightful heir, Cuzco, which Huascar was hated. When small pox, from Mexico, took Huayna Capac’s life in 1527, a civil war ensued, in which Huascar was defeated and held captive in Cuzco (Jenkins 1997: 387). After defeating his half-brother, Atahualpa retired to Cajamarca, when he heard of the Conquistadors’ approach (Jenkins 1997: 387). Atahualpa only regarded the Spanish as raiders and wanted to capture them (Kicza 1996: 346). Delaying his victory march onto the Imperial capital of Cuzco, Atahualpa ignored warnings from spies, wanting to see the Conquistadors. In contrasting signals, he sent warnings and veiled threats of his own to the advancing invaders in the form of gutted, straw-filled ducks hinting at the fate of the Spaniards and also clay models of his fortresses. But he also sent gifts of camelids, guides and food (Rostworowski de Diez Canseco 1999: 126-7). At that time, as Pizarro and his men made their way to meet with Atahualpa in his stronghold in Cajamarca, strong defensible mountain passes were left open, allowing easy access with little fear of a lethal ambush. No resistance or challenge was mounted (Bernand 1988: 138-9). At the Conquistadors’ arrival, emissaries from both sides agreed a meeting the next day in central Cajamarca. Here, Pizarro strategically placed men and horses on three sides of the village square within various buildings with one group in the open with a cannon (Rostworowski de Diez Canseco 1999: 129). There is much confusion over what started the massacre at Cajamarca, whether Atahualpa rejected and threw down the bible offered to him by the Spanish priest or whether the priest panicked and gave a predetermined signal to attack. Atahualpa had an army of 30, 000, the majority of which he kept outside the city, his accompanying guard only armed with small battle-axes (Jenkins 1997: 288). After the bible incident, Pizarro advanced and captured Atahualpa, his men killing around 6000 Incas out of the 30, 000 (Kicza 1996: 346) with over 3000 Inca captured alive compared to the conquistadors slight wound to a horse (Bernand 1988: 132-3). While imprisoned, Atahualpa somehow ordered Huascar’s assassination in Cuzco. Kept alive for ransom and to control the population, Atahualpa was finally executed in 1533 after converting to Christianity; garrotted rather than burned at the stake, an un-Incan death (Innes 1969: 300). Pizarro then marched on Cuzco. After sacking Cuzco, Pizarro installed his own Emperor, Manco Inca (another of Huayna Capac’s sons). Pizarro’s forces then defeated the other Inca armies, put down Manco Inca’s 1535 rebellion and by 1537 all resistance was quashed (Gheerbrant, 1961). Pizarro lost only 20 men from the beginning of the Conquest (Kicza 1996: 346). Raymond Burke 3 The Inca Empire had been around a hundred years old, but not consolidated enough to withstand an attack from a small zealous Conquistador force. Inca underestimation of the Conquistadors, delay in attacking, confusion and complacency were more debilitating than their technological inferiority. There is no doubt that Conquistador technological superiority was dominant with advantages in both physical and psychological factors, and their timely arrival during the civil war also aided in their quest. Pizarro’s victory is a lesson in history that still stands for these times. References: Bernand, C. 1988. The Incas -Empire of Blood And Gold. London: Thames and Hudson. Cunningham-Graham, R.B.1949. The Horses of the Conquest. Norman, Oklahoma: Oklahoma University Press. D'Altroy, T.N. 1992. Provincial Power in The Inka Empire. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. Gheerbrant, A.1961. The Incas -The Royal Commentaries Of The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. New York: The Orion Press. Innes, H. 1969. The Conquistadors. London: Collins. Jenkins, D. 1997. Peru -The Rough Guide. London: Penguin Books, 288 & 387. Kicza, J.E. 1996. Pizarro and the Conquest of the Incas. In: Fagan, B.M. (ed) The Oxford Companion To Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 345-6. Quick, J.1973. Dictionary of Weapons and Military Terms. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc. Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, M. 1999. History of the Inca Realm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.