Working Paper

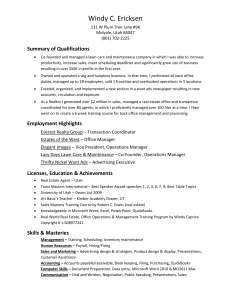

advertisement