Departmental Self Review

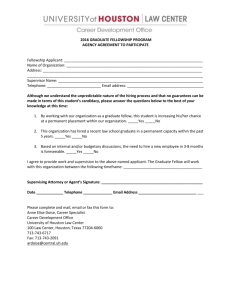

advertisement