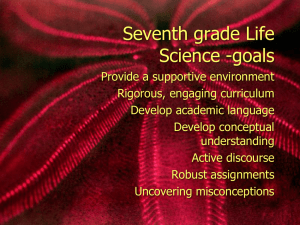

online curriculum development

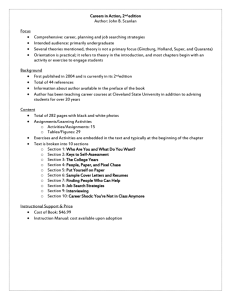

advertisement