Strategic Assessment During Business Risk Audits: The Halo Effect

advertisement

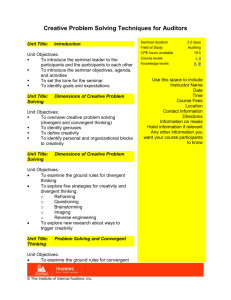

Strategic Assessment During Business Risk Audits: The Halo Effect on Auditor Judgment about Fluctuations in Accounts Ed O’Donnell [ed.odonnell@asu.edu] Joseph J. Schultz, Jr. [Joe.Schultz@asu.edu] W. P. Carey School of Business Arizona State University P.O. Box 873606 Tempe, AZ 85287 June, 2004 We appreciate the suggestions provided by Christine Earley, Steve Glover, Steve Kaplan, Robert Knechel, Lisa Koonce, Natalia Kotchetova, Kurt Pany, Mark Peecher, Steve Salterio, Jeff Wilks, Arnold Wright, and participants in research workshops at Arizona State University, Boston College, the University of Connecticut, Louisiana State University, the University of Waterloo, and the Midyear Meeting of the AAA Auditing Section. This research was supported by a grant from the Small Grant Program at Arizona State University, W. P. Carey School of Business. Strategic Assessment During Business Risk Audits: The Halo Effect on Auditor Judgment about Fluctuations in Accounts ABSTRACT Many auditors are using a business risk methodology where they perform strategic assessment to evaluate the viability of their client’s business model as a preliminary procedure for assessing auditing risks. This study examines whether the holistic perspective that auditors acquire during strategic assessment influences the extent to which they adjust risk assessments when they encounter patterns of changes in accounts that are inconsistent with information about client operations. Based on halo theory from the performance evaluation literature, we hypothesized that auditors who (1) performed (did not perform) strategic assessment and (2) developed favorable (unfavorable) viability assessments during strategic assessment, would be less (more) likely to adjust account- level risk assessments for inconsistent fluctuations. Data from two laboratory experiments using experienced auditors supported both hypotheses. Findings suggest that the halo effect from strategic assessment influences judgment by altering auditor tolerance for inconsistent fluctuations. We found no evidence that strategic assessment diminished the level of effort or attention that auditors devoted to analyzing changes in accounts, or altered their expectations about the size of interperiod expectations in accounts. Strategic Assessment During Business Risk Audits: The Halo Effect on Auditor Judgment about Fluctuations in Accounts I. INTRODUCTION In an attempt to improve their understanding of client business risk, many assurance services firms have developed a new approach to auditing financial statements, one that increases auditor attention to the risks associated with their clients’ business strategy (Lemon, Tatum, and Turley 2000). Auditors who use this business risk approach assess the strategic viability of their client’s business model to develop a holistic understanding of the business processes (Bell et al. 1997). During strategic assessment, auditors focus on the big picture – they learn about their client’s competitive position and identify specific conditions that threaten their client’s ability to create customer value (Eilifsen, Knechel, and Wallage. 2001). Proponents believe that the holistic perspective auditors develop during strategic assessment provides a superior mental model, one that can help them recognize audit risks better than the mental model provided by the transaction-analysis perspective that auditors have traditionally used (Bell, Peecher, and Solomon 2002). Developing a holistic perspective on client business processes has been recommended by the Auditing Standards Board as an important procedure for assessing audit risk (AICPA 2002). Interviews conducted during this study revealed that each of the big- four audit firms requires their auditors to perform strategic assessment early in an audit engagement and document risks that threaten their client’s business model. Although using strategic assessment to develop a holistic perspective on client business operations is becoming a widely-used auditing procedure, decision- making research on strategic assessment is sparse. Studies that examine how strategic assessment influences auditor judgment are just beginning to emerge (see Ballou and Heitger 2004 for a review). This study examines how performing strategic assessment influences auditor judgment about the leve l of misstatement risk associated with patterns of interperiod fluctuations in account balances. While we agree that strategic assessment could enhance auditor judgment with regard to conditions that influence a variety of business risks, we are concerned that this holistic perspective may make it difficult for auditors to recognize risk-related conditions that manifest in accounting details. Studies on performance evaluation have shown that developing an evaluative judgment based on holistic characteristic s has a “halo effect” on subsequent judgments about detailed performance attributes. The halo associated with a favorable (unfavorable) holistic impression decreases (increases) the extent to which performance evaluations are influenced by detailed performance attributes. In other words, people tend to evaluate evidence about detailed attributes of performance to be consistent with their opinion about holistic attributes of the ratee, even when those holistic attributes have little or no direct bearing on the dimensions of performance being evaluated. If the holistic perspective that auditors develop during strategic assessment produces a similar halo effect, then auditors who assess the strategic viability of their client’s business model at a high level may not react appropriately to unfavorable evidence that manifests in details about their clients’ financial performance. Our research question is whether strategic assessment can have a halo effect on auditor judgment about patterns of changes in accounts that increase the risk of financial misstatement. We examined this research question using data from two laboratory experiments where experienced auditors developed holistic judgments about strategic viability and performed 2 analytical procedures to assess misstatement risk for selected financial statement accounts. There were three significant findings. First, performing strategic assessment influenced auditor judgment about misstatement risk associated with fluctuations in accounts. Second, auditors who developed favorable viability judgments during strategic assessment (positive halo) were less likely to increase risk assessments for patterns of inconsistent fluctuations in accounts than auditors who developed unfavorable viability judgments (negative halo). Third, the halo effect from strategic assessment appears to have influenced auditor judgment by altering their tolerance for differences between actual and expected changes in accounts. There is no evidence that strategic assessment altered either the amount by which auditors expected account balances to fluctuate or the amount of effort and attention they devoted to analyzing changes in account balances. These results should not be construed as an indictment of the potential for strategic assessment to improve audit effectiveness. The holistic perspective provided by strategic assessment could enhance auditor judgment across a range of auditing decisions that were beyond the scope of this study (see Ballou and Heitger 2004 for a discussion). The issue for audit practice is not whether to perform strategic assessment, but how to structure the task so that the halo effect is less likely to produce undesirable consequences. In light of our findings, assurance services firms may want to review their procedures for performing strategic assessment to ensure that they are reaping the benefits of a holistic perspective without diminishing the likelihood that their auditors will evaluate evidence from accounting details appropriately. Our findings also motivate research that examines how alternative task structures can be used to optimize the benefits of strategic assessment. 3 The remainder of this study is organized into three sections. Section two describes the theoretical framework that provided a foundation for our study and presents the research hypotheses that inspired our experimental design. Section three explains our research method by (a) describing the task, (b) presenting the results, and (c) discussing the findings for each of our two experiments. The last section summarizes our results across both experiments, acknowledges the limitations of this study, and discusses issues that should be addressed by future research. II. THEORY AND HYPOTHESES Auditors tailor the testing procedures they use during assurance engagements to reduce the likelihood of failing to detect misstated accounts. To target their testing procedures more effectively, auditors attempt to identify financial statement accounts that have a greater risk of misstatement as the result of intentional or unintentional errors. Auditors who use the business risk approach gather preliminary evidence about misstatement risk primarily from two auditing procedures, strategic assessment and analytical procedures, then use this knowledge to design a program of substantive tests (Bell et al. 1997). This study examines how evidence gathered during those two tasks interacts to influence auditor judgment about the risk of misstatement in individual accounts – how knowledge acquired during strategic assessment influences judgment about account- level misstatement risk during analytical procedures. In this section, we describe these two auditing procedures, explain how strategic assessment could produce a halo that influences auditor judgment during analytical procedures, and present our research hypotheses. 4 Auditing Context Strategic assessment provides auditors with a holistic perspective on their clients’ business model (Bell et al. 1997). During strategic assessment auditors learn about the business processes their clients use to bring products and services to market, and they assess business risks that threaten the organization’s ability to execute those processes effectively. For example, the audit methodology used by the firm that provided participants for this study directs their auditors to perform strategic assessment in three sequential phases. First, auditors document client business operations (or update this documentation for continuing clients). Documentation includes, among other things, descriptions of (a) strategic business objectives, (b) the core business processes used to achieve those objectives, (c) internal and external business drivers that constrain those business processes, and (d) strategic management processes the client uses to monitor and control this business model. Second, auditors perform a risk analysis to document strategic business risks and identify significant classes of transactions that could be threatened by those business risks. Third, they perform a process analysis by (a) linking the business risks and significant classes of transactions documented during the second phase to specific business processes documented during the first phase, (b) evaluating the factors that are critical to the success of each process, (c) identifying key performance indicators, and (d) using those metrics to analyze business process performance and assess how well the client is achieving its strategic business objectives. Strategic analysis focuses on business processes and market conditions. The objective of strategic assessment is to understand conditions that influence business risks and evaluate the likelihood that business processes will not work as intended. Auditors turn their attention toward accounting transactions and financial performance when they undertake analytical procedures. 5 The objective of analytical procedures is to assess audit risk for financial statement accounts and evaluate the likelihood that individual account s might be materially misstated. Auditors begin analytical procedures by learning about client operating activities and procedures used to account for business transactions. During analytical procedures, auditors analyze interperiod fluctuations in account balances and search for patterns of changes that are inconsistent with their understanding of client procedures and operations. When auditors believe that fluctuations are consistent with their understanding of client operations, they usually follow a standard program for testing individual account balances, and they may even decrease testing from levels established in prior years. By contrast, when auditors believe that fluctuations are inconsistent, they usually increase misstatement risk for the account and expand subsequent tests. As a result, factors that influence auditor judgment about inconsistent fluctuations in accounts can have a direct impact on the likelihood that they will detect financial misstatements. Throughout this paper, we use the term “inconsistent fluctuations” to describe changes in account balances that are not consistent with other information about client business operations. For example, a significant increase in accounts receivable from last year to this year would be inconsistent with information that sales and accounts receivable turnover are not significantly different from last year. The question that motivated this study is whether the holistic knowledge that auditors develop during strategic assessment influences their evaluative judgment about diagnostic evidence during analytical procedures, when that holistic knowledge is not directly associated with the diagnostic evidence. Acquiring knowledge about the viability of a business model provides a basis for evaluating ability to sustain competitive advantage. This holistic perspective provides direct evidence about conditions that could influence misstatement risk at the entity 6 level. However, while knowledge about the viability of a business model could influence judgment about overall misstatement risk, this holistic perspective has no direct implications for assessing misstatement risk at the account level by evaluating patterns of changes in accounts. Determining whether fluctuations in related accounts are consistent or inconsistent requires knowledge about client operations and current-period conditions and holistic knowledge about strategic viability has no direct diagnostic value. Research has shown that auditors who acquire global or holistic knowledge that is directly associated with a diagnostic task tend to search for and evaluate detailed evidence differently (Peecher 1996) and reach different conclusions after analyzing detailed evidence (Turner 2001). Phillips (1999) found that auditors who evaluated evidence related to accounts that had been classified as low (high) risk were less (more) sensitive to detailed evidence of aggressive financial reporting. Wilks (2002) found that, during a going-concern evaluation, auditors who knew the opinion of the engagement partner before the task began tended to distort their evaluation of detailed evidence to conform with that knowledge. These studies were based on theoretical frameworks that explain the association between diagnostic judgments based on detailed evidence and holistic knowledge that has a direct bearing on the judgment task. Our study examines the association between diagnostic judgments based on detailed evidence and holistic knowledge that has an indirect bearing on the judgment task. This association has not been examined in the audit judgment literature. To develop research hypotheses, we borrowed and transferred a theory from cognitive psychology about how the evaluation of performance attributes is influenced by a halo associated with holistic knowledge that has no direct bearing on ability to perform the task. 7 Halo Theory Performance evaluation research has shown that, when people develop an overall evaluative judgment about an individual, these holistic impressions influence subsequent performance evaluations, even when performance is rated on the basis of criteria that are not associated with attributes that created the holistic impressions. For example, when the rater believes that the ratee is graceful and engaging in social settings, the rater is likely to develop a more favorable subjective evaluation of the ratee’s performance on technical task criteria. Even though social skills have no bearing on the ability to perform the task in question, the rater’s holistic impression of the ratee creates a halo that influences the rater’s evaluation of detailed performance criteria. The halo effect was first suggested by Thorndyke (1920) who found that, when using a set of diagnostic features to evaluate individual performance, people have a predisposition for “suffusing ratings of [diagnostic] features with a halo belonging to the individual as a whole.” In other words, opinions that develop during the process of forming a holistic perspective can create a residual halo that influences the way that people subsequently evaluate performance indicators. People who develop a positive holistic impression tend to evaluate detailed performance attributes more positively as well, and vice- versa. According to halo theory, developing a holistic perspective inspires evaluative judgment driven by global attributes rather than evaluative judgment that focuses on detailed performance indicators (Slovic et al. 2002). Evaluative judgments that produce a halo subconsciously increase the diagnostic value afforded to holistic information about overall characteristics of the ratee, and diminish the diagnosticity of analytic information about specific attributes of ratee performance (Balzer and Slusky 1992). A halo effect influences judgment by decreasing the 8 extent to which detailed performance attributes influence a diagnosis, not by decreasing attention to detailed performance attributes (Lance, LaPointe, and Fisicaro 1994). Halo effects are particularly prevalent when information is evaluated through a top-down task structure, that is, when the rater acquires holistic information before evaluating detailed performance criteria (Murphy, Jako, and Anhalt 1993). People generally interpret detailed diagnostic information to be consistent with holistic preconceptions that develop as a result of opinions they form before the decision is made (Russo, Medvec, and Meloy 1996). They have a tendency to confirm initial evaluative judgments in order to reduce the cognitive dissonance that results from integrating decision cues that are inconsistent with preconceived opinions (Devine, Hirt, and Gehrke 1990). For example, Finucane et al. (2000) found that the holistic impression people formed about the attractiveness of decision alternatives created a halo that reduced the relevance they attributed to analytic information about risk. Research on financial analysis has also shown that acquiring holistic knowledge reduces the salience of risks evidenced by more detailed accounting information (Moreno, Kida, and Smith 2002). Research Hypotheses The holistic opinions auditors form while assessing the viability of a client’s business model influence subsequent judgment about directly-related issues, like client retention risks (Johnstone 2000) and business process risks (Ballou, Earley, and Rich 2004). Halo theory suggests that the holistic perspective auditors develop dur ing strategic assessment will influence judgment about issues that are not directly related to the viability of the business model. If so, auditors who perform strategic assessment should come to different conclusions about the 9 misstatement risk associated with inconsistent fluctuations than auditors who do not perform strategic assessment. Developing a holistic perspective reduces the relevance that people attribute to detailed diagnostic information (Balzer and Slusky 1992). If a holistic perspective diminishes the relevance of detailed evidence, then auditors who perform strategic assessment should place less relevance on inconsistent fluctuations in account balances during analytical procedures than auditors who do not perform strategic assessment. According to halo theory, auditors are likely to place more emphasis on their holistic perspective and less emphasis on accounting details. These associations give rise to our first research hypothesis, which we present in the alternative form as follows: H1: Auditors who perform strategic assessment before they perform analytical procedures will be less likely to adjust their risk assessments for inconsistent fluctuations than auditors who do not perform strategic assessment before analytical procedures. Because people tend to rely on holistic evaluative judgments, the valence of their holistic judgment (positive versus negative) influences the valence of their judgment about detailed performance criteria (Slovic et al. 2002; Lance et al. 1994). People who deve lop favorable holistic opinions are likely to develop more favorable judgments about detailed performance criteria than people who develop unfavorable holistic opinions (Finucane et al. 2000; Murphy et al. 1993). In other words, a developing a holistic perspective creates a halo that influences whether judgments about performance criteria will be favorable or unfavorable. In the context of analytical procedures, halo theory predicts that auditors who develop favorable opinions about the viability of a business model during strategic assessment are likely to view patterns of changes in account balances in a more favorable light than auditors who 10 develop unfavorable opinions about the viability of a business model. As a result, auditors who believe that strategic viability is strong should assess the risk associated with inconsistent fluctuations at lower levels than auditors who believe that strategic viability is weak. These associations give rise to our second research hypothesis, which we present in the alternative form as follows: H2: The viability judgments that auditors develop during strategic assessment will be negatively correlated with the misstatement risk assessments they develop for inconsistent fluctuations during analytical procedures. Hypothesis one predicts that, with regard to misstatement risk, auditors who perform strategic assessment will be less concerned about an inconsistent fluctuation than auditors who do not perform strategic assessment. Hypothesis two predicts that, when auditors perform strategic assessment, they will base diagnostic judgments more on holistic knowledge and less on evidence provided by patterns of fluctuations in accounts. These hypotheses predict that the halo from strategic assessment will diminish the diagnostic relevance afforded to patterns of changes in accounts during analytical procedures and, as a result, auditors will be more tolerant of inconsistent fluctuations when they evaluate account level misstatement risk. However, the effects predicted by our first two hypotheses could also be explained by two other conditions, which must be addressed to provide a rigorous test of halo theory. First, auditors who rely on the evaluative judgments that they develop during strategic assessment may devote less attention to analyzing accounting details. If so, they may be more likely to overlook inconsistent fluctuations. An association between developing a holistic perspective and the level of effort and attention devoted to analyzing detailed performance attributes would not be consistent with halo theory (Lance et al. 1994; Balzer and Slusky 1992). 11 However, an association between viability judgments and the level of effort and attention that auditors devote to analyzing changes in accounts during analytical procedures could account for a decrease in account- level risk assessments among auditors who performed strategic assessment. Second, auditors who develop favorable evaluative judgments during strategic assessment may develop different expectations about changes in account balances than auditors who do not. During analytical procedures, the primary diagnostic for determining inconsistent fluctuations is the difference between the account balance that the auditor expects and the account balance that the auditor observes. If the fluctuations that auditors expect are closer to fluctuations that they actually observe, then the likelihood that a fluctuation will be construed as inconsistent should diminish. We are aware of no study that has examined these issues and, as a result, we have no basis for predicting whether these alternative explanations could account for the effects that we have attributed to halo theory. Therefore, we present null hypotheses to guide our evaluation of these alternative explanations. As the level of attention and cognitive effort that people devote to analyzing decision information increases, their ability to remember that information improves (Birnberg and Shields 1984). For example, Phillips (1999) distinguished levels of attention and cognitive effort based on auditors’ ability to remember the account information that they examined while they assessed misstatement risk. If the evaluative judgment that auditors develop during strategic assessment influences the level of attention and effort that they subsequently devote to analyzing accounting details, then auditors who believe that strategic viability is strong should not remember 12 accounting details as well as auditors who believe that strategic viability is weak. These possibilities lead to the following null hypothesis: H3: There will be no association between the viability assessments that auditors develop during strategic assessment and their ability to remember fluctuations in accounts that they examined during analytical procedures. During analytical procedures, auditors develop expectations about the amount by which accounts should fluctuate between periods based on what they have learned about client operations, then analyze actual changes in account balances to identify fluctuations that are not consistent with their expectations (Libby 1985). The probability that any change in account balance will be considered inconsistent depends on the auditor’s expectations about how much that account should have changed (Koonce 1993). If the evaluative judgments that auditors develop during strategic assessment influence the amount by which they expect accounts to change, then auditors who believe that strategic viability is strong should develop different account balance expectations than auditors who believe that strategic viability is weak. These possibilities lead to the following null hypothesis: H4: There will be no association between the viability judgments that auditors develop during strategic assessment and the expectations that they develop about interperiod changes in account balances. III. METHOD We tested these research hypotheses using data from two laboratory experiments. The first experiment provided evidence for testing hypotheses one and two. The second experiment facilitated a test of hypothesis two under different circumstances and provided evidence for 13 testing hypotheses 3 and 4. The experiments were conducted during two separate national training sessions for senior- level auditors who all worked for the same big- four firm. All participants were classified as seniors. Some had been promoted to senior right before the training session and had little or no experience supervising field work, others had been incharge auditors for as long as four years. Groups of about 30 participants completed the experimental exercise in their classrooms during a one-hour period that had been set aside for conducting research. Each classroom was supervised by a research proctor who distributed and collected the experimental instruments and monitored participant behavior while they completed the task. Both experiments were conducted in three phases. Participants received a package containing three envelopes, labeled phases one, two, and three, and completed the phases in sequence. After completing each phase, participants sealed the materials in the envelope for that phase so that they could not refer to that information during subsequent phases. Research proctors monitored participants’ compliance with these instructions. The same strategic auditing case was used for both experiments with slight changes in the accounting metrics and client operating information. Case materials were patterned after the Loblaw Companies, Ltd. case for a chain of grocery stores (Greenwood and Salterio 2002) and account balances were adapted from the annual report for Safeway, Inc. The controller for a regional grocery chain (similar to the one described in the case) provided metrics for key performance indicators and reviewed the materials for realism. Information about client operations was grouped by strategic business processes in the same format as the audit support software that participants used in the field. The comparative account balance information that participants used for analytical procedures was presented in 14 four columns, which included balances for this year and last year, and the amount and percent of change between years. Information for key performance indicators included the same four columns of information plus the industry best-practices standard. In an attempt to increase auditor sensitivity to unusual improvements in performance, all cases indicated that the company was currently negotiating a merger with a larger competitor. In experiment one, some of the cases included an inconsistent-fluctuation manipulation while others did not. All cases stated that unit sales prices, sales mix, and product costs had not significantly changed from last year to this year, which suggests that fluctuations in cost of sales should be proportional to fluctuations in sales. In the case with no inconsistent fluctuation, sales and cost of sales increased by approximately the same amount (5.2% and 4.9%, respectively). However, in the case that included the inconsistent fluctuation, the increase in sales and cost of sales was disproportional (5.2% and 0.9%, respectively). This seeded condition resulted in an increase in gross profit that was inconsistent with information about unit sales prices, sales mix, and product costs. We patterned our seeded condition after the inconsistent fluctuation created by Bedard and Biggs (1991) that involved misallocation of overhead costs for a manufacturing client. For the grocer described in our case, this pattern of changes in two related accounts (sales and cost of sales) could, among other things, signal a misstatement that resulted from misallocation of distribution costs. Experiment One The first experiment employed a two-by-two, between-subjects design. The presence or absence of the inconsistent fluctuation was one of the crossed factors. The other was whether or 15 not participants performed strategic assessment before they performed analytical procedures. Misstatement risk assessments for cost of sales was used as the dependent variable. Including cases that did and did not contain inconsistent fluctuations provided a basis for (a) validating that the inconsistent- fluctuation manipulation increased misstatement risk and (b) evaluating how the requirement to perform strategic assessment influenced auditor risk assessments for a case that did and did not contain an inconsistent fluctuation. Evidence that the inconsistent fluctuation manipulation and the requirement to perform strategic assessment interact indicates that auditors who performed strategic assessment reacted differently to the inconsistent fluctuation than auditors who did not perform strategic assessment. Procedure Participants began phase one by answering questions about their auditing experience. Next, they read information about the audit engagement, control risk assessments, the client’s industry, business operations, and history with the firm, and key business processes. They reviewed a current-year balance sheet and income statement, then provided a baseline misstatement risk assessment for inventory, sales, cost of sales, and store expenses on a scale from one (low) to seven (high). These pre-task risk assessments provided a metric that was used to control for between-subject differences in misstatement risk expectations that existed prior to the experimental manipulations. After providing pre-task risk assessments, participants who did not perform strategic assessment began phase two. Participants who performed strategic assessment were provided with two paragraphs of information that described the client’s business strategy and explained how the client was attempting to execute the strategy. They were also provided with five key performance indicators that served as benchmarks for gauging how well the strategy was being 16 accomplished. The five key performance indicators were taken from information about client operations that was provided to all participants when they assessed misstatement risk during phase two. Using a scale from one (low) to seven (high), participants assessed the likelihood that the company would be able to execute its strategy successfully. During phase two, all participants analyzed information about client operations and provided post-task risk assessments for inventory, sales, cost of sales, and store expenses on a scale from one (low) to seven (high). Partic ipants were asked to assess misstatement risk across four accounts to help disguise the seeded- inconsistency manipulation and reduce demand effects. During phase three participants completed a debriefing questionnaire and were asked to provide their e- mail address if they wanted a summary of the results. Responses to the debriefing questionnaire were used to check the validity of the case materials. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of experimental tasks for this experiment. insert figure 1 here Results A total of 90 auditors with an average of 2.9 years of auditing experience (standard deviation = 1.3) participated in the first experiment. Research proctors reported that most participants took about 45 minutes to complete the exercise and all finished within one hour. Descriptive statistics for all measured variables are presented in table 1. insert table 1 here 17 Hypothesis Tests We used analysis of covariance to calculate metrics for our tests; post-task risk assessments for cost of sales was the dependent variable; our two crossed factors were the independent variables; pre-task risk assessments for cost of sales was the covariate. Results of our analysis are presented in table 2. insert table 2 here Before testing hypothesis 1, we verified that the inconsistent fluctuation we seeded as one of our manipulations actually increased risk assessments for cost of sales. As shown in panel A of table 2, the inconsistent fluctuation had a significant influence on misstatement risk assessments (f = 4.88; p < .05). The mean post-task risk assessments for cost of sales were 3.9 for cases with no seeded inconsistency compared with 4.5 for the case with the seeded inconsistency. It appears that our inconsistent fluctuation manipulation was successful. Hypothesis one predicts that auditors who perform strategic assessment will be less likely to adjust their risk assessments for inconsistent fluctuations than auditors who do not perform strategic assessment. We tested this prediction with planned comparisons for differences between adjusted cell means. As shown in panel B of table 2, for auditors who did not perform strategic assessment, the average risk assessment of 5.0 for the case with the inconsistent fluctuation is significantly (p < .05) greater than the average risk assessment of 3.9 for the case without the inconsistent fluctuation. However, there is no significant difference in cost of sales risk assessments related to the inconsistent fluctuation for auditors who performed strategic assessment. Auditors who performed strategic assessment did not adjusted their risk assessments for the inconsistent fluctuation but auditors who did not perform strategic assessment 18 significantly increased their risk assessments in the presence of a the inconsistent fluctuation. H1 is supported. Hypothesis two predicts that, for auditors who perform strategic assessment, misstatement risk assessments for the inconsistent fluctuation will decrease as the viability judgments that they developed during strategic assessment increase. We tested this prediction, using data from the 48 auditors who performed strategic assessment, by regressing post-task cost of sales risk assessments on viability judgments, a dummy variable for the inconsistent fluctuation, and pre-task cost of sales risk assessments (the covariate). Results are presented in table 3. insert table 3 here Consistent with H1, the insignificant parameter estimate for the inconsistent fluctuation manipulation suggests that auditors who performed strategic (all of the participants in this sample partition) did not adjust their risk assessments for the inconsistent fluctuation. The negative, significant (p < .01) parameter estimate for strategic viability judgments suggests that misstatement risk assessments increased as strategic viability judgments decreased. H2 is supported. Additional Analyses The auditors who participated in this study worked for a firm that requires them to perform strategic assessment before they analyze account- level misstatement risk. One explanation for our findings could be that participants who did not perform strategic assessment were more skeptical because they did not follow their normal routine. As a result, the unfamiliar 19 task structure might have inspired a more rigorous analysis. We used data from the debriefing questionnaire to evaluate this possibility. After participants completed their risk assessments, they responded to two questions about the case materials that they had evaluated. They were asked to rate the similarity between the format used to present information in this exercise and the format used by the their firm’s audit support software on a scale from one (not similar) to seven (very similar). Average ratings for participants who performed strategic assessment were 3.5 compared with 3.6 for participants who did not perform strategic assessment. Participants were also asked to rate how well the information they examined during this exercise helped them to understand the business processes their client uses to create customer value on a scale from one (not well) to seven (very well). Average ratings for participants who performed strategic assessment were 3.8 compared with 4.0 for participants who did not perform strategic assessment. T-tests indicate that performing strategic assessment had no significant influence on either of these ratings, which suggests that familiarity with the task structure did not influence the results. Another explanation for our findings is that auditors who were required to perform strategic assessment were more fatigued when they performed analytical procedures and did not put forth as much effort as auditors who were not required to perform strategic assessment first. Participants completed the experimental task in less than an hour, immediately after returning from a lunch break. It is unlikely that experienced auditors who perform this type of analysis on a regular basis were particularly fatigued after analyzing one page of information and the five key performance indicators that were provided for strategic assessment. However, our experimental design provided data for assessing this possibility. 20 Auditors who were did not perform strategic assessment before analytical procedures were required to perform that analysis during phase three, before they completed the debriefing questionnaire, but after they had completed analytical procedures during phase two. During strategic assessment, all auditors were required to document the rationale for their viability assessments. There was no significant difference between the number of words used for that documentation by auditors who performed strategic assessment before analytical procedures (mean = 38 words; standard deviation = 28 words) and auditors who performed strategic assessment after analytical procedures (mean = 34 words; standard deviation = 17 words). There was also no significant difference in the average viability ratings between these two groups. These findings provide no evidence that fatigue confounded our results. Discussion Our findings suggest that halo theory can explain the association between strategic assessment and auditor judgment about fluctuations in accounts. However, these results suggest that a widely- used auditing procedure, which is becoming institutionalized in practice, may have undesirable side effe cts. We are reluctant to report findings of that nature without replicating our results. Furthermore, the generalizability of our findings is limited by two external validity issues. First, we have no evidence that our inconsistent fluctuation would be a concern on an actual audit engagement. The senior-level auditors who participated believed that our inconsistent fluctuation increased misstatement risk for cost of sales. However, we do not know whether the same concern would be expressed by more experienced auditors, like firm partners who ultimately must sign the audit opinion. If not, then our findings have limited implications for audit practice. 21 Second, we have no evidence that differences in participants’ post-task cost of sales risk judgments would translate into differences in audit effort. The results from our first experiment indicate that performing strategic assessment can influence account-level risk assessments. However, there is no evidence that differences in these risk assessments reflect differences in auditor judgment about the level of testing necessary for substantiating account balances. If differences in these risk assessments do not correspond to differences in anticipated levels of audit effort, then the findings of this study will be of little significance to practicing auditors. Our second experiment provided evidence for addressing both of these validity issues and allowed us to replicate our findings with regard to the halo effect under different conditions. Experiment two also generated data for testing H3 and H4, which provides a basis for evaluating the mechanism by which the halo effect influences auditor judgment. Experiment Two In the second experiment, participants assessed misstatement risk over two consecutive years for the same client. For both years, participants were told to assume that strategic assessment had already been performed by the engagement partner and they were provided with a summary of his conclusions about the viability of the client’s business model. Next, they were provided with information about core business processes and fluctuations in accounts, and asked to assess misstatement risk for inventory, sales, cost of sales, and store expenses. All participants were provided with the same information about changes in accounts and they were all provided with information from the engagement partner’s strategic assessment before they performed analytical procedures. 22 All participants received the same information for the first year but we manipulated the strategic assessment information they received for the second year to be either favorable or unfavorable. We chose to manipulate rather than elicit viability assessments for experiment two. During the first experiment, participants had an opportunity to develop their own viability assessments by actually performing a limited strategic assessment. However, as shown in table 1, the viability assessments that participants provided ranged from 1 to 6 (on a seven-point scale) with a standard deviation of 1.1. In other words, even though participants all received the same information for strategic assessment during experiment one, their conclusions about the viability of their client’s business model were extremely heterogeneous. We decided to manipulate viability assessments during experiment two to create a more stable variable. We created favorable and unfavorable strategic viability conditions as follows. For the first year, all participants were told that (a) the client had changed their strategy during the year, (b) sales revenue and market share had not significantly changed, (c) net income had remained relatively stable, and (d) the engagement partner had concluded it was still too early to develop any meaningful assessment about the viability of the new strategy. For the second year, participants assigned to the favorable-viability-assessment condition were told that the engagement partner believed the new strategy may achieve the results that the client intended. Their case indicated that sales growth for the second year was 3.2% while the average sales growth in the client’s market was only 1.9%. Net income had increased by 1.8% and the client had increased its market share. Participants assigned to the unfavorable- viabilityassessment condition were told that the engagement partner believed the new strategy may not achieve the results that the client had hoped for. The ir case indicated that sales growth during the 23 second year was only 3.2% while the average sales growth in the client’s market was 4.5% and, although net income had increased by 1.8%, the client had lost market share. Procedure During phase one, participants were provided with information about (a) overall engagement risk, (b) strategic business risks (including information about strategic assessment), (c) business process analyses, and (d) control risk assessments. This information was patterned after the documentation provided by the audit support software that they use in the field. Next, they were provided with comparative account balances and key performance indicators for the first year and the previous year (including the amount and percent of change) and asked to assess misstatement risk for inventory, sales, cost of sales, and store expenses. Participants used a 100point scale where 0 indicated very low risk and 100 indicated very high risk. Next, participants were told to assume that they had returned to audit the same client for the following year, that the audit for the previous year had gone smoothly, that there had been no proposed adjusting entries, and that the client had received an unqualified opinion. They were provided with information about strategic assessment (either favorable or unfavorable). They were told that there had been no significant changes in business processes or management personnel, and that unit sales prices, sales mix, and product costs had remained stable. However, the case also indicated that engagement risk had increased from 25 to 35 (on a 100-point scale) because the client was currently engaged in merger negotiations, and that control risk had increased from 20 to 25 (on a 100-point scale) because the client had implemented a significant upgrade to its supply chain management software. We included these conditions to increase participants’ focus on risk factors during analytical procedures. 24 After reading information about the second year, participants were directed to indicate whether they expected balances for inventory, sales, cost of sales, and store expenses to decrease, not change, or increase and document their expectations on a scale from one (decrease significantly) to seven (increase significantly). This requirement was used by McDaniel and Kinney (1995) to increase auditor attention to fluctuations in account balances during analytical procedures. We included this requirement to (a) increase the likelihood that participants would notice the inconsistent fluctuation and (b) provide metrics for evaluating whether strategic assessment influences auditor expectations about changes in account balances. After documenting their expectations, participants sealed phase-one materials in an envelope and began phase two. During phase two, participants were provided with second- year balances for the metrics they analyzed during phase one and asked to provide misstatement risk assessments for inventory, sales, cost of sales, and store expenses using the same 100-point scale. Next, for each of those four accounts, participants were asked to indicate whether they expected the amount of time spent gathering and evaluating evidence to substantiate the account balance to decrease, not change, or increase compared to year one. If they expected the amount of time to change, participants were also asked to indicate the percent of increase or decrease in audit effort. During phase three participants answered debriefing questions, completed a surprise recognition task, and were given an opportunity to provide their e- mail address if they wanted a summary of the results. The surprise recognition task provided data for differentiating levels of attention and cognitive effort across the experimental conditions. In multiple-choice format, participants were asked to recall the change in inventory, sales, cost of sales, and store expenses from the first year to the second year. They were provided with the same five answer choices for 25 each question, of which four represented the actual fluctuations in accounts (inventory was 1.8%, sales was 3.2%, cost of sales was 0.9%, store expenses was 2.7%, and the fifth answer choice was 3.0%). Results A total of 46 auditors with an average of 2.6 years of auditing experience (standard deviation = 1.0) participated in the second experiment. Research proctors reported that most participants took about 25 minutes to complete the exercise and all finished within 40 minutes. Descriptive statistics are presented in Panel A of Table 2. Before testing our hypotheses, we evaluated the validity of our experimental materials in three ways. First, we checked our manipulation of the halo from strategic assessment. During the debriefing questionnaire participants were asked to rate their perception of the likelihood that their client’s business strategy would succeed on a scale from one (not likely) to seven (very likely). Mean success ratings for participants who received the unfavorable viability assessment were 3.0 while mean success ratings for participants who received the favorable viability assessment were 4.4 (t = 4.13, p < .01). It appears that our manipulation worked as we intended. Second, we evaluated whether participants’ misstatement risk assessments influenced their expectations about the level of audit effort that would be needed to substantiate an account balance. There is a significant (p < .05) positive Spearman correlation between change in risk assessment and anticipated audit effort for each of the four accounts that participants analyzed, which suggests that auditors who assessed risk at higher levels also believed they would have to spend more time gathering evidence to test that account. This finding provides evidence that the risk assessments we used as dependent variables for testing our hypotheses are a reasonable proxy for auditor concern about the likelihood of financial misstatement. 26 Third, we validated our inconsistent fluctuation manipulation with an expert panel. We asked audit partners with four of the former big- five firms (all had at least eight years experience as an audit partner) to complete the case exercise that included the favorable viability assessment (but did not require them to document expectations). All four increased misstatement risk for cost of sales during the second year (two increased by 15 and two increased by 10) and the average increase for cost of sales was larger than the average increase for the other three accounts (average increases in risk from the first year to the second year were 1.6 for sales, 8.8 for store expenses, 10.0 for inventory, and 12.5 for cost of sales). All four audit partners also expected audit effort for cost of sales to increase during the second year (anticipated increases were 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%). This evidence verifies that auditors with substantial expertise believed the inconsistent fluctuation would be a cause for concern. Hypothesis Tests Hypothesis two predicts that auditors who developed favorable viability judgments from strategic assessment would rate misstatement risk at lower levels than auditors who developed unfavorable viability judgments. We calculated the amount by which misstatement risk for cost of sales (rated on a scale from 1 to 100) changed from year one to year two, then used this within-subjects change score to replicate our test of H2. The average increase in risk assessments for auditors who received the favorable viability judgment from strategic assessment was 1.0 compared with 13.3 for auditors who received the unfavorable viability judgment (t = 2.73; p < .01). We also used the risk assessments from year one and year two to perform a repeatedmeasures analysis of variance. The results were the same. H2 is supported once again. Hypothesis three addresses the level of attention and effort that auditors devoted to evaluating changes in account balances during analytical procedures, using ability to remember 27 as a proxy. We used data gathered during the surprise recognition task to examine participants’ ability to remember the change in each of the four accounts that they analyzed during the task. Of the 48 auditors who participated in this study, 35 (73%) remembered the change in sales, 23 (48%) remembered the change in cost of sales, 25 (52%) remembered the change in inventory, and 22 (46%) remembered the change in store expenses. Chi square tests indicate that there was no significant difference (at the p < .10 level) in the proportion of participants who remembered correctly between the two viability assessment conditions. These findings suggest that favorable viability judgments did not alter the amount of attention and cognitive effort auditors devoted to analyzing fluctuations in accounts. There is no evidence for rejecting the null hypothesis H3. Hypothesis four addresses differences in auditor expectations about the size of interperiod fluctuations in account balances. Recall that participants documented their expectations about changes in inventory, cost of sales, and store expenses after they received information about strategic assessment for the second year but before they were provided with information about actual changes in account balances. Participants used a seven-point scale where one represented “decrease significantly” and seven represented “increase significantly”. On average, participants who received the favorable viability judgment rated their expectations about the change in cost of sales at 4.5 and auditors who received unfavorable viability judgments rated their expectations at 4.6 (p > .10). These findings suggest that favorable viability assessments had no influence on auditor expectations about the size of interperiod fluctuations in accounts. There is no evidence for rejecting the null hypothesis H4. Discussion Results from experiment two provide additional evidence in support of halo theory. Although auditors who received favorable (unfavorable) viability assessments rated 28 misstatement risk at lower (higher) levels, there is no evidence that favorable viability assessments influenced either (1) the cognitive effort and attention that auditors devoted to analyzing to changes in account balances during analytical procedures or (2) auditor expectations about how much account balances should cha nge between years. As a result, this experiment provides evidence that, consistent with halo theory, viability judgments from strategic assessment influence auditor judgment about patterns of changes in accounts by altering their tolerance for unexpected fluctuations. IV. SUMMARY This study examined whether auditors who acquire holistic information about the strategic viability of their client’s business model before they analyze fluctuations in accounting metrics might assess the risk of misstatement in individual accounts differently from auditors who do not acquire that holistic perspective. Based on findings from performance evaluation research, we hypothesized that risk assessments rendered by auditors who developed a holistic perspective on client operations would be influenced by a halo effect that increased their tolerance for patterns of changes in related accounts that should increase misstatement risk. This theoretical framework suggests that strategic assessment will influence judgment because it increases emphasis on holistic information and reduces emphasis on detailed performance measures. Our results suggest that misstatement risk assessments were less sensitive to an inconsistent fluctuation in account balances (1) when auditors performed strategic assessment before they performed analytical procedures and (2) when they developed a favorable opinion 29 about the viability of their client’s business model during strategic assessment rather than an unfavorable opinion. These results must be interpreted with care. Although the auditors who participated in this study were provided with an opportunity to acquire a holistic perspective on client operations, they did not perform strategic analysis with the degree of rigor that would be applied in the field. In practice, auditors review business processes and evaluate business risks in more depth, a process that would allow them to develop a more comprehensive mental model. Creating a more complete mental model could make the effects of strategic assessment even stronger. On the other hand, a more complete mental model might have altered the way that participants searched for and evaluated evidence, and increased their sensitivity to the inconsistent fluctuation that we seeded to the case materials. Another significant difference between audit practice and our experimental setting is the level of expertise that was brought to bear on the risk assessment process. In this study, seniorlevel auditors performed analyses and made the type of decisions they are responsible for in the field. However, in practice, their conclusions are scrutinized by managers and partners who are more likely to recognize patterns of account balances that represent inconsistent fluctuations (Bonner and Lewis, 1990). In the field, the level of expertise that the audit team as a whole can apply to analytical procedures and risk assessment may compensate for the shortcomings in judgment exhibited by the seniors who participated in our study. Both audit practice and the audit judgment literature could benefit from research that examines how alternative task structures influence the interaction between strategic assessment and analytical procedures. Research has shown that changing the way information is organized and presented during diagnostic auditing tasks can alter judgment (Ricchiute 1992) and help 30 auditors recognize risk factors (O’Donnell and Schultz 2003). Altering task structures to direct auditor attention toward specific information can increase the extent to which that information influences audit judgment tasks (Knapp and Knapp 2001). Perhaps the audit methodologies developed to accommodate the business risk approach need some fine tuning to increase the salience of evidence that manifests in detailed accounting information. For example, a lack of aud itor sensitivity to accounting details was apparently a factor in the audit failure at WorldCom, a debacle that involved a firm that pioneered the use of strategic assessment. WorldCom’s auditors failed to interpret a 3.8 billion dollar increase in transmission equipment and decrease in routine maintenance costs as a pattern of fluctuations in account balances that signaled material financial misstatement (Glater and Eichenwald 2002). Research on the business risk approach in general and strategic assessment in particular could help audit practitioners develop more effective holistic perspectives. 31 Figure 1 Flow of Tasks for Experiment One Strategic Assessment Document pre-task misstatement risk assessments No Strategic Assessment Document pre-task misstatement risk assessments Phase 1 Phase 2 Perform strategic assessment and document viability judgments * * * Perform analytical procedures and document misstatement risk Perform analytical procedures and document misstatement risk * * * Perform strategic assessment and document viability judgments Complete debriefing questionnaire Complete debriefing questionnaire Phase 3 32 Table 1 Descriptive Statistics for Experiment One n Mean SD Min Max Pre-task misstatement risk for cost of sales from 1 (low) to 7 (high) 90 4.1 1.3 1.0 7.0 Post-task misstatement risk for cost of sales from 1 (low) to 7 (high) 90 4.1 1.5 1.0 7.0 Strategic viability rating of client’s business model from 1 (low) to 7 (high) * 48 4.0 1.1 1.0 6.0 Years of auditing experience 90 2.9 1.3 0.8 10.1 * Only the 48 auditors who performed strategic assessment rated the viability of the client’s business model 33 Table 2 The Influence of Strategic Assessment on Risk Assessments for Cost of Sales Panel A: Analysis of Covariance Dependent Variable = Post-task misstatement risk for cost of sales df Sum of Squares F-Statistic 4 85 74.12 152.09 10.36 *** Strategic assessment Inconsistent fluctuation Interaction 1 1 1 6.28 8.74 4.30 3.51 * 4.88 ** 2.41 Pre-task misstatement risk for cost of sales 1 43.83 24.49 *** Model Error Panel B: Adjusted Cell Means Strategic Assessment No Strategic Assessment Condition Mean No Inconsistent Fluctuation 3.8 n = 24 Inconsistent Fluctuation 4.0 n = 24 3.9 n = 22 5.0 n = 20 3.9 4.5 t = 0.23 t = 2.39 ** * p < .10; ** p < .05; 34 *** p < .01 Condition Mean 3.9 t = 0.52 4.5 t = 2.57 ** t = 2.21 ** t = 1.87 * Table 3 The Influence of Strategic Viability Judgments on Risk Assessments for Cost of Sales OLS Regression: n = 48; R-Square = 0.36; F-Statistic = 8.31 *** Dependent Variable = Post-task misstatement risk for cost of sales Intercept Inconsistent fluctuation Strategic viability judgment Pre-task misstatement risk for cost of sales * p < .10; Estimate Standard Error T-Statistic 4.18 0.04 - 0.54 0.46 0.83 0.36 0.15 0.13 5.00 *** 0.12 3.58 *** 3.42 *** ** p < .05; 35 *** p < .01 Table 4 Descriptive Statistics for Experiment Two Mean SD Min Max Cost of sales misstatement risk for first year from 1 (low) to 100 (high) 37.9 16.4 2.0 80.0 Cost of sales misstatement risk for second year from 1 (low) to 100 (high) 45.1 17.2 3.0 90.0 Expected percent of increase <decrease> in time needed to test cost of sales in second year 14.6% 12.9% - 5.0% 50.0% 2.7 1.1 0.8 8.0 Years of auditing experience 36 REFERENCES American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). 2002. Understanding the Entity and Its Environment and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement. Exposure draft for proposed statements on auditing standards issued by the Auditing Standards Board on December 2, 2002. New York: AICPA. Ballou, B., C. Earley, and J. Rich. 2003. The impact of strategic positioning information on auditor judgments about business process performance. Working Paper, University of Connecticut. Ballou, B. and D. Heitger. 2004. Judgment and decision- making research in a dynamic auditing environment. Working paper, Auburn University. Balzer, W. and L. Slusky. 1992. Halo and performance appraisal research: A critical examination. Journal of Applied Psychology 77: 975–985. Birnberg, J. and M. Shields. 1984. The role of attention and memory in accounting decisions. Accounting Organizations and Society 9.3-4: 365-83; Bedard, J. and S. Biggs. 1991. Pattern recognition, hypothesis generation and auditor performance in an analytical task. The Accounting Review (July): 622-42. Bell, T., F. Marrs, I. Solomon, and H. Thomas. 1997. Auditing Organizations Through a Strategic-Systems Lens. KPMG Peat Marwick, LLP. Bell, T., M. Peecher, and I. Solomon. 2002. The strategic-systems approach to auditing. In Cases in Strategic-Systems Auditing, edited by T. Bell and I. Solomon. KPMG, LLP: 1-34. Bonner, S. and B. Lewis. (1990). Determinants of auditor expertise. Journal of Accounting Research (Supplement): 1-20. Devine, P., E. Hirt, and E. Gehrke. 1990. Diagnostic and confirmation strategies in trait hypothesis testing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58.6: 952-63. Eilifsen, A., R. Knechel, and P. Wallage. 2001. Application of the business risk audit model: A field study. Accounting Horizons 15.3: 193-208. Finucane, M., A. Alhakami, P. Slovic, and S. Johnson. 2000. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 13.1: 1-17. Glater, J. and K. Eichenwald. 2002. Turmoil at WorldCom: The accounting. New York Times (June 28). Greenwood, R. and S. Salterio. 2002. Loblaw Companies, Ltd. In Cases in Strategic-Systems Auditing, edited by T. Bell and I. Solomon. KPMG, LLP: 165-210. 37 Johnstone, K. 2000. Client-acceptance decisions: Simultaneous effects of client business risk, audit risk, auditor business risk, and risk adaptation. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 19.1: 1-26. Knapp, C. and M. Knapp. 2001. The effects of experience and explicit fraud risk assessment in detecting fraud with analytical procedures. Accounting, Organizations and Society 26.1: 25-37. Koonce, L. 1993. A cognitive characterization of audit analytical review. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory (Supplement): 57-76. Lance, C. J. LaPointe, and S. Fisicaro. 1994. Tests of three causal models of halo rater error. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Performance 57: 83-96. Lemon, M., K. Tatum, and W. Turley. 2000. Developments in the Audit Methodologies of Large Accounting Firms. London, UK: ABG Professional Information. Libby, R. 1985, Availability and the generation of hypotheses in analytical review, Journal of Accounting Research, 648-67. McDaniel, L. and W. Kinney. 1995. Expectation-formation guidance in the auditor’s review of interim financial information. Journal of Accounting Research 33.1: 59-76. Moreno, K., T. Kida, and J. Smith. 2002. The impact of affective reactions on risk decision making in accounting contexts. Journal of Accounting Research 40.5: 1331-1349. Murphy, K., R. Jako, and R. Anhalt. 1993. Nature and consequences of halo error: A critical analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 78.2: 218-25. O’Donnell, E. and J. Schultz. 2003. The influence of business-process- focused audit support software on analytical procedures judgments. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory 22.2 (September): 265-80. Peecher, M. 1996. The influence of auditors’ justification processes on their decisions: A cognitive model and experimental evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 34.1 (Spring): 125-40. Phillips, F. 1999. Auditor attention to and judgments of aggressive financial reporting. Journal of Accounting Research 37.1: 167-90. Ricchiute, D. 1992. Working-paper order effects and auditors’ going-concern decisions. The Accounting Review 67.1: 46-58. Russo, J. V. Medvec, and M. Meloy. 1996. The distortion of information during decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 66.1 (April): 102-10. 38 Slovic, P., M. Finucane, E. Peters, and D. MacGregor. 2002. Rational actors or rational fools: Implications of the affect heuristic for behavioral economics. Journal of SocioEconomics 31: 329-42. Thorndyke, E. 1920. A constant error in psychological ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology 4: 25-29. Turner, C. 2001. Accountability demands and the auditor’s evidence search strategy: The influence of reviewer preferences and the nature of the response (belief vs. action). Journal of Accounting Research 39.3 (December): 683-706. Wilks, T. 2002. Predecisional distortion of evidence as a consequence of real-time audit review. The Accounting Review 77.1 (January): 51-71. 39