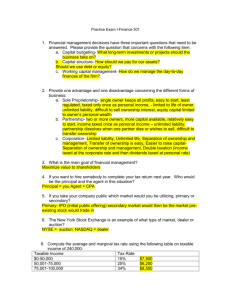

Review of the Debt and Equity Tax Rules

advertisement