Campbell soup mini-case

advertisement

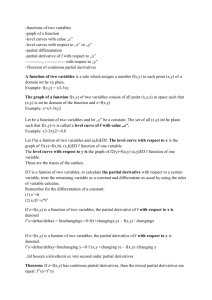

Campbell Soup mini-case (Derivatives) Companies are exposed to different types of market risks. These risks arise because the profitability of business operations is sensitive to fluctuations in several factors such as commodity prices, foreign currency exchange rates, and interest rates. Market forces determine these factors. For example, a gold mining company can control the volume and, at least partially, the cost of gold it produces. However, its profitability depends on the spot price of gold, a price it can neither control nor reliably forecast. This exposes a gold mining company to commodity price risk. As another example, a U.S. equipment manufacturer can contract to supply machinery to a foreign buyer in its local currency. If the dollar strengthens against the local currency before the buyer makes payment, the U.S. manufacturer loses. This exposes the U.S. manufacturer to foreign currency risk. As still another example, a real estate financier can offer a fixed-rate mortgage to a homebuyer. If interest rates increase, the financier may find it difficult to fund the mortgage in a profitable manner. This exposes the real estate financier to interest rate risk. To lessen these market risks, companies enter into hedging transactions, or hedges for short. Hedges are contracts that seek to insulate companies from market risks. A hedge is similar in concept to an insurance policy, where the company enters into a contract that ensures a certain payoff regardless of market forces. A hedge is possible because different parties are affected in different ways by market risks. For example, while a gold mining company is concerned with a drop in gold prices, a jewelry maker is concerned with an increase in gold prices. This means a gold miner and a jewelry maker are potentially interested in a contract to sell (buy) gold at a future date for a fixed price. This is called a forward contract, and often is transacted in a commodities market. Financial instruments such as futures, options, and swaps are commonly used as hedges. These financial instruments are called derivative financial instruments, or simply derivatives. A derivative is a financial instrument whose value is derived from the value of another asset, class of assets, or economic variable such as a stock, bond, commodity price, interest rate, or currency exchange rate. However, a derivative contracted as a hedge can expose companies to considerable risk. This is either because it is difficult to find a derivative that entirely hedges the risk exposure or because the parties to the derivative contract fail to understand the potential risks from the instrument. Companies also use derivatives to speculate. Counterparties that bear risk in a derivative contract are called speculators. Accounting for Derivatives All derivatives, irrespective of their nature or purpose, are recorded at fair value on the balance sheet. This is an important requirement that increasingly affects balance sheets of companies, both because of the growing magnitude of derivatives and their volatile nature. However, unlike fair value accounting for investment securities, where only assets and not corresponding liabilities are marked to market, the accounting for derivatives affects both sides of transactions (wherever applicable) by marking to market. This means if a derivative is an effective hedge, the effects of changes in fair values usually should cancel out and have a minimal effect on financial statements. Unrealized gains and losses on fair value hedges (fixed-for-floating interest rate swaps, futures contracts or options to hedge the fair value of a security, and the hedge of a fixed future commitment to sell a commodity as a specified price) as well as on the related asset or liability are recorded in income and affect current profitability. As long as the hedge is effective, this accounting does not affect the financial statements in a material manner as balance sheet and income statement effects are largely offsetting. Alternatively, unrealized gains and losses arising from cash flow hedges (floating-forfixed interest rate swaps, and hedges of forecasted sales of commodities are reported as part of other comprehensive income (e.g., as a component of stockholders’ equity and not in current income) until the effective date of the transaction, after which they are transferred to income and are offset by the effect of the transaction itself. For example, a company might want to lock in the value of investment securities it owns by selling put options. Gains and losses on the options are deferred in other comprehensive income until the security is sold, at which time the accumulated gain or loss on the option is transferred into income and offsets the gain or loss on the security sold. Finally, unrealized gains and losses on speculative hedges are reported immediately income. Objectives for Using Derivatives The first aim in analysis of derivatives is to learn a company’s objectives for use of derivatives. Most companies allegedly use derivatives for hedging. Still, some companies use derivatives for trading and/or speculative purposes. Sometimes, these trading or speculative activities arise as part of risk management services offered by the company. For example, Enron’s Wholesale Operations and Services division offers price risk management services for energy-related commodities such as natural gas and crude oil with a variety of financial instruments. Also, some managers use derivatives to speculate about movements in underlying market variables. Identifying a company’s objectives for use of derivatives is important because risk associated with derivatives is much higher for speculation than for hedging. In the case of hedging, risk does not arise through strategic choice. Instead it arises from problems with the hedging instrument, either because the hedge is imperfect or because of unforeseen events. In the case of speculation, a company is making a strategic choice to bear the risk of market movements. Some companies take on such risk because they are in a position to diversify the risk (in a similar manner as an insurance company). More often, managers speculate because of “informed hunches” about market movements. We must realize that many companies (implicitly) speculate even when they suggest derivatives are used for hedging. One reason for this is when a company hedges specific exposures it does not always hedge overall company risk (see discussion below). Risk Exposure and Effectiveness of Hedging Strategies Once an analyst concludes a company is using derivatives for hedging, the analyst must evaluate the underlying risks for a company, the company’s risk management strategy, the activities of a company to hedge its risks, and the effectiveness of its hedging operations. Unfortunately, disclosures currently mandated under SFAS 133 do not always provide meaningful information to conduct a thorough analysis. For example, Campbell Soup utilizes fixed-to-variable swaps to achieve a targeted percentage of variable rate debt and takes on interest rate risk in the process. The company does not, however, provide information to describe the method by which it arrives at this targeted percentage, nor does it describe the level of interest-rate risk that it is undertaking in the process. Likewise, the company does not provide information of the degree of foreign exchange exposure and the extent to which this has been mitigated by the use of crosscurrency swaps and forward contracts. SFAS 133 was principally designed to provide readers with current values of derivative instruments and the effect of changes in these values on reported profitability. Oftentimes, however, the fair market values are immaterial and the notional amounts do not provide information necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of the company’s hedging activities. Companies are not required to quantify, for example, the extent to which exposures have been mitigated via hedging activities which would, if disclosed, provide investors and creditors with a greater understanding of the effectiveness of the hedging strategy. Transaction-Specific versus Company-wide Risk Exposure Companies hedge specific exposures to transactions, commitments, assets, and/or liabilities. While hedging specific exposures usually reduces overall risk exposure of the company to an underlying economic variable, companies rarely use derivatives with an aim to hedge overall company-wide risk exposure. Moreover, accounting rules disallow hedge accounting unless the hedge is specifically linked to an identifiable asset, liability, transaction, or commitment. This raises a broader question: what is the ultimate purpose of hedging? If the purpose of hedging is to reduce overall business risk by reducing the sensitivity of a company’s cash flows (or net asset values) to a specific risk factor, then does hedging individual risk exposures achieve this? It probably does, but not necessarily. The relevant analysis question is whether rational managers enter into derivative contracts that increase overall company-wide risk. In some cases the answer is yes. Such actions can arise because of the size and complexity of modern businesses and the difficulty of achieving goal congruence across different divisions of a company. For example, the treasury department of a company might be responsible for controlling financing cash flows and then enter into interest rate swaps to reduce volatility of interest payments even though these interest payments could be negatively correlated with the company’s operating cash flows. Similarly, the American and European divisions of a company might hedge currency risk exposures with conflicting aims because each division is attempting to manage its specific risk exposure without considering overall company-wide risk. An analyst must evaluate overall company-wide effects of derivatives and be aware that hedging specific risk exposures does not necessarily ensure hedging of company-wide risk. Inclusion in Operating or Nonoperating Income Another analysis issue is whether to view unrealized (and realized) gains and losses on derivative instruments as part of operating or nonoperating income. To the extent derivatives are hedging instruments, then unrealized and realized gains and losses should not be included in operating income. Also, the fair value of such derivatives should be excluded from operating assets. This classification is clear for derivative instruments that hedge interest rate movements since the underlying exposure (usually interest expense or interest income) is itself a nonoperating item. For hedging of other types of risks, such as foreign currency and commodity price risks, it is less clear. That is, one classifies gains and losses (and fair values) from derivatives as nonoperating when: (1) hedging activities are not a central part of a company’s operations and (2) including effects of hedging in operating income conceals the underlying volatility in operating income or cash flows. However, when a company offers risk management services as a central part of its operations (as many financial institutions do), we must view all speculative gains and losses (and fair values) as part of operating income (and operating assets or liabilities). This mini-case is designed to give you a greater understanding of the use of derivatives. I use the Campbell Soup Company to illustrate the practical use of derivatives. Please review the financial statements of Campbell Soup. Focus on the discussion of derivatives in the MD&A (Market Risk Sensitivity – pages 34-36) as well as in note 18. Please answer the following questions: 1. Describe, specifically, what Campbell Soup is trying to accomplish with its interest rate exposure derivatives. 2. Describe, specifically, how Campbell Soup mitigates its foreign exchange risk. 3. What effects do derivatives have on its balance sheet and income statement?