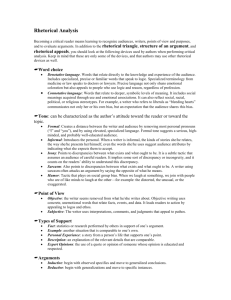

terms for rhetorical analysis

advertisement

Fealy 1 TERMS FOR RHETORICAL ANALYSIS Rhetoric – the art of using language effectively or persuasively. Rhetorical situation consists of the writer, the occasion, the purpose and audience, the genre and the context. Context – the larger social or cultural context and the ongoing conversation on the topic. Reading the articles one should pay attention to the larger sense of culture, politics, and history in which the article appears; potential bias or point of view; place of publication; how the ongoing conversation affects what you think; how your own cultural, political, ethnic, or personal Rhetorical Analysis – an examination of how well the components of an argument work together to persuade or move an audience. Rhetorical Trinity: Writer, Audience, Context are the corners of a triangle with text in the middle. The focus of rhetorical analysis are the questions about WHO is claiming WHAT and the PURPOSE of the claim. Enthymeme – a statement that links a claim to a supporting reason. In classical rhetoric, an enthymeme is a syllogism (a vehicle of deductive reasoning) with one term understood but not stated: Socrates is mortal because he is a human being. (The understood term is All human beings are mortal) Aristotle used the term ENTHYMEME to describe a very ordinary kind of sentence that includes both a claim and a reason: Enthymeme = Claim + Reason In the absence of hard facts, claims may be supported with other kinds of compelling reasons. The formal study of principles of reasoning is called LOGIC – a syllogism – a vehicle of deductive reasoning ETHOS – the self-image a writer creates to establish trustworthiness, authority, and credibility with the reader PATHOS – a strategy in which a writer tries to generate specific emotions (fear, envy, anger, pity) in an audience to dispose it to accept a claim LOGOS – a strategy in which the writer uses facts, evidence, and a chain of logical reasoning to make audience accept a claim. STASIS THEORY Another way of categorizing arguments is to consider their status or stasis – the kinds of issues they address. This categorization system is called Stasis Theory – in ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, rhetoricians defined a series of questions by which to examine legal cases. The questions would be posed in sequence, because each depended on the question preceding it: Did something happen? What is its nature? What is its quality? What actions should be taken? Figurative language: Tropes And Schemes - Figures have traditionally been classified into two main types: TROPES, which involve a change in the ordinary signification or meaning of a word or phrase; and SCHEMES, which involve a special arrangement of words. Fealy 2 TROPES: Metaphors: A metaphor makes an implicit comparison between dissimilar ideas or things without using like or as Similes: A simile is an explicit comparison between two essentially different ideas or things that uses the word like or as to link them. Analogies: Analogies usually involve explaining one idea or concept by comparing it to something else. An analogy is typically a complex or extended comparison. Personification: the writer attributes human qualities to ideas or objects. (Blond October) Signifying: used in African American English, in which a speaker cleverly and often humorously needles the listener.( p. 383). In simple words it is to brag for no practical purpose. The use of overstatement for special effect. Hyperbole - a figure of speech which is an exaggeration. "I nearly died laughing," Understatement - to represent as less than is the case. To state or present with restraint especially for effect ("I am just going outside and may be some time." - Captain Lawrence Oates, Antarctic explorer, before walking out into a blizzard to face certain death, 1912) Rhetorical question - A question asked merely for effect with no answer expected. "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" says the persona of Shakespeare's 18th sonnet. Antonomasia - Shorthand substitution of a descriptive word or phrase for a proper name can pack arguments into just one phrase: "the little corporal" for Napoleon. Sarcasm: a sharp and often satirical or ironic utterance designed to cut or give pain Irony is an implied discrepancy between what is said and what is meant. 1. Verbal irony is when an author says one thing and means something else. 2. Dramatic irony is when an audience perceives something that a character in the literature does not know. 3. Irony of situation is a discrepancy between the expected result and actual results. SCHEMES Schemes are figures that depend on word order: Parallelism: The laws of our land are said to be “by the people, of the people, and for the people.” Antithesis – the use of parallel structures to mark contrast or opposition: “That’s one step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” (Neil Armstrong) “Marriage has no pains, but celibacy has no pleasures.” (Samuel Johnson) Inverted word order when parts of the sentence are not in the usual subject-verb-object order: “Hard to see, the dark side is.” (Yoda) Back and forth rocked the boat. Out of the volcano billowed smoke. Overhead shone the sun. Anaphora, or effective repetition: For everything there is a season . . . a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up what is planted.–Bible, Ecclesiastes. To die, to sleep; to sleep: perchance to dream.–Shakespeare, Hamlet. One of the most famous examples of anaphora in Shakespeare occurs in Act II, Scene I, Lines 40-68. Reversed structure: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for the country.” J.F.K. (inaugural address, 1961) When you are asked to do a "rhetorical analysis" of a text, you are being asked to apply your critical reading skills to break down the "whole" of the text into the sum of its "parts." You try to determine what the writer is trying to achieve, and what writing strategies he/she is using to try to achieve it. Reading critically also means analyzing and understanding how the work has achieved its effect. Fealy 3 While the three cornerstones around the text are the writer, audience, and context, we can also apply Stasis Theory (Did something happen? What is its nature? What is its quality? What actions should be taken?) and Enthymemes (unspoken beliefs, values, and assumptions) to analyze rhetorical strategies. The questions below will help you explore various rhetorical strategies and focus on elements that strengthen or weaken the argument. However, rhetorical analysis purpose is not to describe techniques and strategies; instead, show how the key devices in an argument actually make it succeed or fail. Show readers where and why an argument makes sense and where it falls apart by quoting from the text, explaining your reasoning, and providing evidence from other texts. The hardest part of rhetorical analysis is keep your distance as it doesn’t matter whether you agree or disagree with an argument and focus only on how well/poorly the argument works. Thus, your claim should address the rhetorical effectiveness of the argument itself, NOT the opinion or position it takes and should indicate important relationships between various rhetorical components, NOT just list them. Hence, you’re not simply announcing the evidence, but analyze its significance and appropriatness. Questions for Rhetorical Analysis Who is the writer/organization? Any bias? What is the major claim? Who is the audience? What is the purpose – To explain? To inform? To anger? Persuade? Amuse? Motivate? Explore? Sadden? Ridicule? Anger? Is there more than one purpose? Does the purpose shift at all throughout the text? What is the context - the larger social or cultural context and the ongoing conversation on the topic? Reading the articles one should pay attention to the larger sense of culture, politics, and history in which the article appears; potential bias or point of view; place of publication; how the ongoing conversation affects what you think; how your own cultural, political, ethnic, or personal background affects what you believe. What appeals does the argument use – emotional, logical, ethical? What evidence does the writer use – facts, experts’ testimony, personal experience? What claims are advanced in the argument – fact, definition, cause-and-effect, value, policy? How is the argument presented? What is its organization and structure? What is the logic of its order? How does this structure create and/or constrain the text’s meaning? How does it shape the text and its argument? How does the language, style or tone of the argument work to persuade an audience? The basics of style are word choice, figurative language (similes, metaphors), sentence structure, and paragraphing. How does the writer use qualifiers? (To qualify their thoughts writers use such qualifiers, for example, as sometimes, often, presumably, unless, almost) Does the writer use irony, humor, or sarcasm to be persuasive? Does the writer use a very formal tone, a highly technical vocabulary, or an impersonal voice to signal that an argument is for experts only? Does the writer present his/her claim fairly addressing the opposition and providing counter arguments for their major claims? What values and believes does the text promote and how they shape the argument and limit or expand the rhetorical strategies available to the writer?