Rhetorical Analysis

advertisement

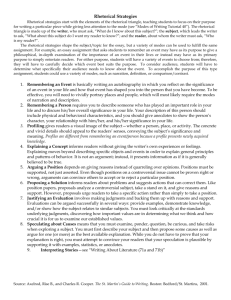

Rhetorical Analysis Becoming a critical reader means learning to recognize audiences, writers, points of view and purposes, and to evaluate arguments. In addition to the rhetorical triangle, structure of an argument, and rhetorical appeals, you should look at the following devices used by authors when performing critical analysis. Keep in mind that these are only some of the devices, and that authors may use other rhetorical devices as well. Word choice Denotative language. Words that relate directly to the knowledge and experience of the audience. Includes specialized, precise or familiar words that speak to logic. Specialized terminology from medicine or law speaks to doctors or lawyers. Precise language not only shuns emotional coloration but also appeals to people who use logic and reason, regardless of profession. Connotative language: Words that relate to deeper, symbolic levels of meaning. It includes social meanings acquired through use and emotional associations. It can also reflect social, racial, political, or religious stereotypes. For example, a writer who refers to liberals as “bleeding hearts” communicates not only her or his own bias, but an expectation that the audience shares this bias. Tone: can be characterized as the author’s attitude toward the reader or toward the topic. Formal: Creates a distance between the writer and audience by removing most personal pronouns (“I” and “you”), and by using elevated, specialized language. Formal tone suggests a serious, highminded, and probably well-educated audience. Informal: Introduces the personal. When a writer is informal, the kinds of stories she/he relates, the way she/he presents her/himself, even the words she/he uses suggest audience attributes by indicating what she expects them to accept. Irony: Points to discrepancies between what exists and what ought to be. It is a subtle tactic that assumes an audience of careful readers. It implies some sort of discrepancy or incongruity, and it counts on the readers’ ability to understand this discrepancy. Sarcasm: Also points to discrepancies between what exists and what ought to be. A writer using sarcasm often attacks an argument by saying the opposite of what he means. Humor: Tactic that plays on social group bias. When we laugh at something, we join with people who are of like minds to laugh at the other—for example: the distorted, the unusual, or the exaggerated. Point of View Objective: the writer seems removed from what he/she writes about. Objective writing uses concrete, unemotional words that relate facts, events, and data. It leads readers to action by appealing to logos and ethos. Subjective: The writer uses interpretations, comments, and judgments that appeal to pathos. Types of Support Fact: statistics or research performed by others in support of one’s argument. Example: another situation that is comparable to one’s own. Personal Experience: a story from a person’s life that supports one’s point. Description: an explanation of the relevant details that are comparable. Expert Opinions: the use of a quote or opinion of someone whose opinion is educated and respected. Arguments Inductive: begin with observed specifics and move to generalized conclusions. Deductive: begin with generalizations and move to specific instances.