MLA Sample Essay

advertisement

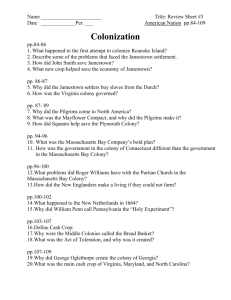

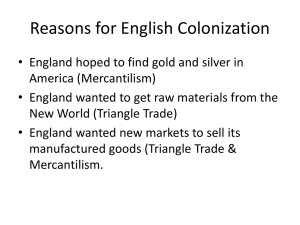

Batchelor 1 Kevin Batchelor Yirush History 145A 4 March 2004 Comparing Early Colonial Success in Jamestown and Puritan New England When compared to the Jamestown Colony, the relatively immediate success of Puritan colonists in New England, though a result of many factors, can be attributed primarily to the fact that their society revolved around their religious beliefs. The Virginia swampland was characterized by an unforgiving and disease harboring climate, but did provide fertile soil ideal for cultivation of crops. In the 1630s, a little over two decades after the Jamestown colony was begun in Virginia, Puritans from England set up new colonies further north along the Atlantic coast of North America in New England. They, too, faced climatic problems. The land in New England was much less fertile than in Virginia; rock laden and densely forested, it was not well suited for farming. The climate was harsh; winter was much colder than Virginia and the summer was relatively dry. Disease, however, was much less prevalent, the colony not being constructed on a malarial swamp. Colonists in New England and in Virginia all faced difficult lives. Each colony had to find a way to overcome the assortment of hardships they would encounter. The social, political, and economic structures of each community played the largest role in the ability of the colonists to overcome those barriers to success. In the end, colonies in both regions were successful, but the Puritans had a much easier time establishing their community primarily because of the social structure provided for in the tenants of Puritanism. The English colonists who initially settled Jamestown, Virginia came for one major reason: money. While conversion of Native Americans to Christianity was certainly an Batchelor 2 important task in the eyes of some settlers, the opportunity to make money was, for most, the primary incentive for coming to the New World (Perry 25). The Spanish and Portuguese returned from the New World with substantial wealth, mostly in the form of gold and gems, but also spices and exotic fruits and vegetables not available in Europe. The English, naturally, wanted to share in the riches which seemed readily available in the New World. The earliest English expeditions to the New World were composed of aristocrats and well to do English gentlemen. These men were little interested in the necessities of survival. The hard work of planting crops and constructing shelters and defense systems, certainly tasks which should have taken priority over treasure hunting, were inadequately addressed; the men, instead, did little but try to “dig gold, wash gold, refine gold, [and] loade gold” (Smith 37). Of course, the lack of gold in Virginia made this an utterly unsuccessful course of action. The secondary motivation for early settlement, the conversion of Native Americans, proved infeasible (Miller 39). By 1610 any notions of converting of Native American’s were gone. The colonists were struggling simply to survive and religious concerns had all but vanished from the colonists minds (Andrews 270). Though the Jamestown colonists were struggling, long term survival was not of critical to most of the earliest English settlers in the New World. Most of those who came in search of riches planned to stay only a brief period of time. The gentlemen expeditioners wanted to quickly extract what fortunes they could and return home to England to enjoy the benefits of their newfound wealth in the “civilized world”. This lack of commitment to permanent colonization presented a problem: rather than work to establish a sustainable community the men did only what they felt was necessary to survive, thus the disease ridden settlement of Jamestown began to collapse almost from its inception. Virginia’s hot, humid climate, though ideal for Batchelor 3 growing some crops, was not ideal for unprepared, unseasoned settlers, unwilling to labor in the fields (Morgan 158). Jamestown’s proximity to malarial swampland only added to the struggle to avoid illness which quickly overcame colonists suffering from malnutrition. During, the winter of 1609, often referred to as “the starving time,” only a year and a half removed from the first settlers’ arrival, more than 80% of the colonists died from disease, starvation, or Native American attacks (Kupperman 24-25). As dramatic as those numbers are, perhaps more amazing is the fact that until John Smith took control of the colony nobody seemed to care to find a solution to the problem. Even the men who were dying were indifferent; rather than get out of bed and struggle for their lives many simply laid down and waited for the inevitable release of death (Kupperman 29). The winter of 1609, however, may have provided the Jamestown colony with the key to its survival. Out of “the starving time” arose a leader who was willing to enforce the rigid discipline the colony needed to survive. In 1609 John Smith implemented what was, essentially, a system of military government in Jamestown. The codification of Smith’s system under Thomas Dale in 1611 provided the social structure necessary for the perpetuation of the colony. Dale’s Laws strictly scripted the day to day activities of the colonists. Regulations were implemented to ensure that sanitary living conditions were maintained: people were no longer permitted to dump wash basins into the street, trash had to be removed from outside doorways, and houses had to be kept in states of good repair and tidiness (Dale 41). All of these measures reduced the incidence of disease among the colonists. Economic codes regulated the colonists trade with the Native Americans, prevented negligence in the tending of land, and forced people be prepared to work a designated number of hours every day (Dale 41-42). Dale’s Laws also instituted a strict religious policy within the colony; all citizens were required to attend Church twice daily. This reinforced the Batchelor 4 strict regiment upon which the colony would need to rely for its survival. It made the law something passed down from God not just the work of man. God, who was seen as responsible for not only events which occurred within the colony, but also for the very existence of that colony and the land upon which it was built, was a much more powerful deterrent than any court system (Dale 39-40). Despite the success of Dale’s Laws in improving the quality of life in Jamestown, the regulations could not yet generate population stability in the colony. Nonetheless, the strict codes laid the groundwork necessary for eventual success. Still, it was not until the 1640s and 50s that the Jamestown Colony began to survive without a constant influx of new men. The first Puritan settlers arrived in New England in the 1630s, just as Jamestown was beginning to make the transition from a treasure hunters’ camp into a viable permanent colony. Fleeing England to start a religious settlement, the Puritans intended from the outset to form a permanent colony in the New World. While the Puritans saw corruption everywhere in the Anglican Church, they did not wish to separate themselves from that church; instead, they wanted New England to serve as a model for reforms within the Church of England (Winthrop 62-63). Many Puritans decided to risk the stability of their lives in England for something new in New England. They believed a new colony in the New World would give them the opportunity to live in a manner which was in compliance with what they thought was God’s will. Puritans looked to the New World to provide a refuge from the sins of those around them (Ames 70-78). The Puritans found that New England was not an easy place in which to create their Puritan refuge. Certainly the climate was much less deadly than in Virginia, but while that saved lives, it also made growing crops difficult. The densely forested and rocky soil required Batchelor 5 extensive work to prepare for planting. Even after clearing the trees and underbrush, tilling the land proved a major chore simply because of the sheer number of rocks which had to be removed (Middleton 76). Of course, the struggles of colonists in Virginia proved useful for the Puritans; having read reports of the difficulties of survival in the New World they were able to better prepare themselves for survival when deciding what supplies to bring from England. Additionally, the close proximity of the successful Plymouth Colony provided the Puritan settlers in New England with a support system. Nonetheless, John Winthrop’s “City on a Hill” was built on the toil of committed laborers (Winthrop 68). Whatever the advantages of the New England environment, workers had to clear and plant fields for farming, construct buildings and roads, and then maintain what they had built. The Puritans approached this process with a certain zeal which was infrequent, if not unheard of, in Virginia even under the watchful eyes of John Smith and Thomas Dale. This particular attitude towards work (which would, in a fairly short period of time improve Puritan lives well beyond the lives of those in Virginia) can only be attributed to the social ideals of Puritan society. A demographic comparison of the Virginia and New England colonists proves quite enlightening. Jamestown was primarily composed of men coming to America looking to earn money; New England was a religious colony populated by families. The male to female ratio was nearly balanced in New England even at the earliest stages of colonization (Norton 598). In New England, it seems, women and children in the streets replaced the litter which, untended, had piled up in Jamestown. The presence of women and children undoubtedly provided some motivation for men to maintain higher standards of living in New England than in Jamestown. After all, it was shameful enough for a man to fail to live up to the standards of Puritan society, but it was utterly reprehensible for him to neglect the needs of his family (Cox). Batchelor 6 The focus of Puritan society was clearly on the endurance of the community not the economic success of the individual. New England Society itself, according to John Winthrop, was based on that very principle. He argued that the commonwealth was formed by the consent of its members. Winthrop believed, therefore, that those members must all have an active interest in each other’s well being. Furthermore, he reemphasized the importance of the family within the community by clearly defining the parallel between the two. The “family is a little common wealth,” Winthrop stated, “and a common wealth is a greate family” (Winthrop 68). This connection would have reinforced the importance of building a strong community in the minds of Puritan settlers. Outside of social life, citizens were expected to live under the guidance of very exacting economic standards. Even if a craftsmen or trader fell upon hardship he was expected to suffer losses rather than increase his prices and harm the community. John Cotton reported several guidelines along which businessmen were expected to operate. He deemed it unjust for a man to buy cheap goods and sell them at high price. Even if a traders goods were “lost by casualty of sea, or, etc...it is a lost cast himself by providence, and he may not ease himself of it by casting it upon another” man (Cotton 108). These ideas, as detailed by Cotton, moved the society away from the quest for profit and toward mutually beneficial relationships between citizens. Social mores, economic policy, family relations, and government were all tightly bound to the Church. The structure of Puritan society was defined by its religion. The Puritan notion of the community was defined by the ideal Christian society. The laws established within the New England colonies strongly reflected the Mosaic Laws (Aristocracy in Massachusetts and Virginia 280). The rigidity of those laws constructed the relatively strict society in which Puritans lived. Enforcement of those laws, though through a court system, was managed by the Puritan Church. Batchelor 7 The church had ultimate authority within Puritan society. The desire to remain an upstanding citizen of both the church and the community and avoid the social stigma of failing to live up to societies standards would have been a driving force for new colonists to exert the effort necessary to succeed as individuals and as a community. This helped maintain the long term stability of the colony. While the problems facing colonists in Virginia and New England were different, they were not completely dissimilar. Both groups had to deal with problems which arose from the land on which they were settled. New Englanders had to clear large tracts of rocky woodland while Virginians had to build and live on swamps. While in Virginia malarial swampland posed a health hazard. The climate in New England was much harsher, especially during the winter. Eventually both societies flourished, but the Puritan colonists had much more immediate success. While some of this can be attributed to the overall healthier environment in New England, clearly the decisions made by Jamestown colonists about what activities demanded their labor had a major impact. Most of these decisions seem to have been based on the desire for money. The Puritans came to the New World with entirely different motivations. Rather than make money, they wanted to establish a community. Understanding the concept of a Puritan community is the key to understanding their immediate success in the New World. Early Virginia settlers were all trying, basically, to gain wealth independently. The tenants of the Puritan Church forced the New England colonists to work together as an integrated community; this allowed them to succeed immediately in the New World. Essentially, Puritanism immediately laid the groundwork for colonial success in New England while that same structure took several decades to develop in Virginia. Batchelor 8 Works Cited Andrews, K.R., et al. ed. The Westward Enterprise: English Activities in Ireland, the Atlantic and America 1480-1650. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1978. “Aristocracy in Massachusetts and Virginia.” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine (Apr. 1918) Cox, Amy. “History 145A Lecture: February 27, 2004" Green, Jack P. ed., Settlements to Society: 1584-1763. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1975. Middleton, Richard. Colonial America: A History, 1565-1776. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1992. Miller, Perry. “Religion and Society in the Early Literature: The Religious Impulse in the Founding of Virginia.” The William and Mary Quarterly. (Jan. 1949) Morgan, Edmund S., American Slavery, American Freedom, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1975. Norton, Mary Beth. “The Evolution of White Women’s Experience.” American Historical Review. (1984)