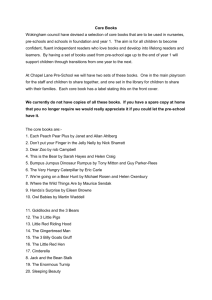

3. list of objectives

advertisement