Should the Colonies Declare Independence

advertisement

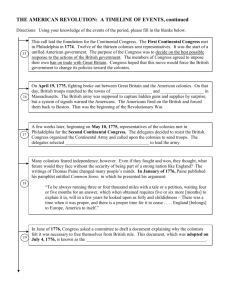

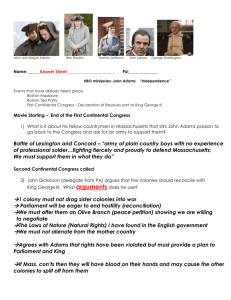

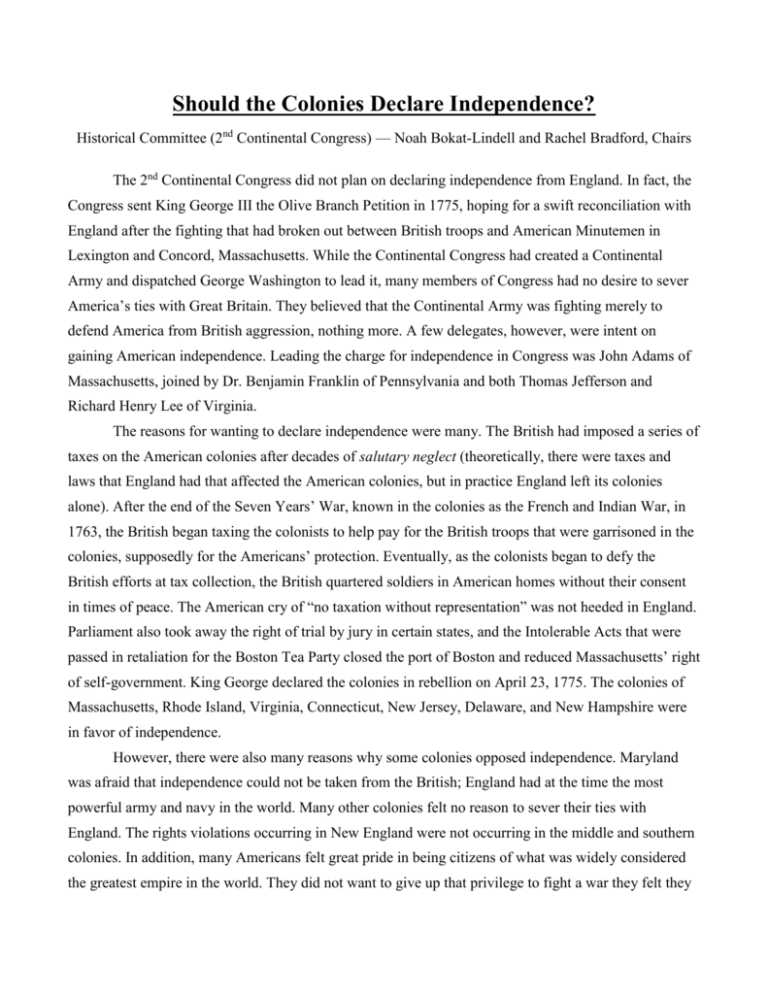

Should the Colonies Declare Independence? Historical Committee (2nd Continental Congress) –– Noah Bokat-Lindell and Rachel Bradford, Chairs The 2nd Continental Congress did not plan on declaring independence from England. In fact, the Congress sent King George III the Olive Branch Petition in 1775, hoping for a swift reconciliation with England after the fighting that had broken out between British troops and American Minutemen in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. While the Continental Congress had created a Continental Army and dispatched George Washington to lead it, many members of Congress had no desire to sever America’s ties with Great Britain. They believed that the Continental Army was fighting merely to defend America from British aggression, nothing more. A few delegates, however, were intent on gaining American independence. Leading the charge for independence in Congress was John Adams of Massachusetts, joined by Dr. Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and both Thomas Jefferson and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. The reasons for wanting to declare independence were many. The British had imposed a series of taxes on the American colonies after decades of salutary neglect (theoretically, there were taxes and laws that England had that affected the American colonies, but in practice England left its colonies alone). After the end of the Seven Years’ War, known in the colonies as the French and Indian War, in 1763, the British began taxing the colonists to help pay for the British troops that were garrisoned in the colonies, supposedly for the Americans’ protection. Eventually, as the colonists began to defy the British efforts at tax collection, the British quartered soldiers in American homes without their consent in times of peace. The American cry of “no taxation without representation” was not heeded in England. Parliament also took away the right of trial by jury in certain states, and the Intolerable Acts that were passed in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party closed the port of Boston and reduced Massachusetts’ right of self-government. King George declared the colonies in rebellion on April 23, 1775. The colonies of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Virginia, Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware, and New Hampshire were in favor of independence. However, there were also many reasons why some colonies opposed independence. Maryland was afraid that independence could not be taken from the British; England had at the time the most powerful army and navy in the world. Many other colonies felt no reason to sever their ties with England. The rights violations occurring in New England were not occurring in the middle and southern colonies. In addition, many Americans felt great pride in being citizens of what was widely considered the greatest empire in the world. They did not want to give up that privilege to fight a war they felt they could not win. Also, many of the delegates to the Continental Congress were wealthy aristocrats who did not want to see their property taken threatened by the chaos that they believed would result from revolution. The southern states did not want to rush to war, but rather wanted to wait longer and attempt a reconciliation with England. But perhaps the most important reason for opposing independence was the fact that no colony had ever broken off from its mother country before. It was a new concept that those unhappy with their current form of government could revolt and form a new one. There was great fear, well justified, that the colonists would be committing treason by declaring independence. If they were to lose, the delegates of the Congress would more than likely be hanged as traitors. The fiery lead Pennsylvania delegate, John Dickinson, led the fight against independence. Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and certain delegates from other colonies also opposed independence. New York, having received no instructions from its legislature in regards to independence, abstained on any votes dealing with the issue. The Continental Congress decided that any resolution regarding independence needed to be approved unanimously, without any colony voting against it. On July 2, 1776, the 2nd Continental Congress approved Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence. But it could have turned out quite differently. We will be simulating that tenuous debate over independence in the 2nd Continental Congress, free to choose a different path from the actual historical outcome. Will we declare independence from England, or will we stay tethered to our mother country and attempt to negotiate a peace? It’s up to you. A Resolution on Independence Whereas these colonies have been abused by King George III and his Parliament for over a decade; Whereas Parliament has taxed these fair colonies without the consent of its people, who are not represented in the British Parliament; Whereas the right to trial by jury has, in many cases, been denied the people of these colonies; Whereas British troops have been quartered in our homes without our consent in times of peace; Whereas King George and his Parliament have attempted to deny the people of these colonies of its unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; Whereas a people have a right to overthrow a government that does not protect its natural rights and institute a new government in its place; Whereas it would be necessary for the colonies, upon declaring independence, to seek the support of powerful allies such as Spain or France; Whereas a new form of government must of necessity be created to manage the new country that shall be created once the independence of these United Colonies is agreed to by this Congress; Resolved by the Congress of the United Colonies, 1. That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved. 2. That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances. 3. That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.