Collapse of Communism

advertisement

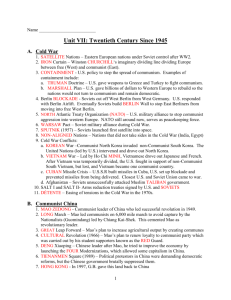

Collapse of Communism Article Outline Introduction; Causes of the Collapse of Communism; Gorbachev, Perestroika, and Glasnost; Events of 1989; The End of the USSR; The Aftermath I INTRODUCTION Collapse of Communism, the disintegration of Communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) between 1989 and 1991. II CAUSES OF THE COLLAPSE OF COMMUNISM The basic causes were economic stagnation, the rise of nationalist resistance to the ideology of communism, attempts to increase democracy, and changes in the international political environment. These factors were all interlinked and the Soviet leadership failed to devise a sequence of reforms that would enable it to sustain its rule. By the 1980s the Communist regimes were all coming close to economic stagnation, in part caused by enormous defence expenditures. The “Star Wars” initiative proposed by the United States president Ronald Reagan in 1983 threatened to provoke an arms race that would impose even greater burdens on people who had experienced improvements in their standard of living and wanted more. There had been earlier attempts in Eastern Europe at reforming the Communist system from within (1956 in Hungary (see Hungarian Revolution) and 1968 in Czechoslovakia (see Prague Spring), but these had been repressed by Soviet leaders who feared losing the buffer zone between the Soviet Union and the West that had been established after World War II. What had changed by the mid-1980s was the emergence in 1985 of Mikhail Gorbachev, representing a new political generation, as general-secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). III GORBACHEV, PERESTROİKA, AND GLASNOST Initially Gorbachev’s first priority was reviving economic dynamism at home through greater discipline, but little was achieved. Consequently, he launched what he claimed was a “scientific” programme of economic restructuring (perestroika). This aimed at reducing the bureaucratic economic planning machine with greater reliance on the forces of the free market. When this ran into resistance from bureaucrats, he tried to mobilize pressure from below through greater transparency (glasnost), by increasing the powers of elected local soviets, and appealing to grass-roots support. What he wanted was a modern, civilized, democratic, prosperous, “European”, form of socialism. However, as the dislocation of the economy increased, the regime granted increasing opportunities for people to complain and protest. They took full advantage. At the same time Gorbachev also tried to reduce the burden of military spending by reaching arms control agreements with the West. Here he had greater success and as reforms stalled at home, provoking increasing turmoil, he concentrated increasingly on foreign policy. He pulled Soviet forces out of Afghanistan, where they had been embroiled in a war since 1979, and then negotiated the historic SALT agreements with the US on the limitation and reduction of nuclear weapons, but this then constrained rather than widened his freedom to manoeuvre at home. IV EVENTS OF 1989 The pace of events quickened in 1989. In Poland at the beginning of the year round-table talks between the government and the independent trade union movement Solidarity led to a commitment to free elections in August, won by Solidarity. In the spring massive daily demonstrations in Tiananmen Square, in the Chinese capital Beijing, aroused hopes of wider change in the Communist world (though the protests were violently suppressed by the Chinese army at the beginning of June). Also during the spring Hungary began removing the worn-out barbed wire along its frontier with Austria. During the summer increasing numbers of East Germans travelled east to Hungary, circumventing the Berlin Wall, then wandered across from Hungary into Austria while others sought refuge in West German embassies in several East European countries. The local authorities did little to obstruct them, increasing the sense of a historic opportunity opening up. Protests gathered momentum more or less spontaneously. The old leadership in the German Democratic Republic appealed to Moscow for support, but the younger Gorbachev refused to contemplate a “Chinese solution” (as the East German leader Erich Honecker had put it,implying mass shootings). He knew that this would have ruined détente with the West and with that his plans for reform in the Soviet Union and throughout the Communist bloc. The nerve of the old leaders in Eastern Europe began to crack. Gorbachev wanted new, like-minded reformist leaders. Honecker was quickly replaced by a reformer, Egon Krenz, but this failed to quell the protests. Mass demonstrations began, nervously at first, but then with increasing confidence when it became clear that they no longer faced brutal repression. They spread to the rest of Eastern Europe and one regime after another fell. On November 9 the East German regime effectively admitted defeat and opened the Berlin Wall. As people flooded across the divide, the East German government began talks with West Germany over reunification. The same day saw the fall of the longserving Bulgarian Communist leader, Todor Zhivkov. Later in the month the new reformist Communist leadership in Hungary lost a referendum over the powers of the president. The Czechoslovak Communist leadership was forced to resign after several days of peaceful protests beginning on November 17 (the “Velvet Revolution”). The cycle ended on December 22 with the downfall of Nicolae Ceauşescu in Romania, who was executed with his wife three days later. Within a space of four months communism in Eastern Europe had collapsed. The veteran civil rights protester and playwright Václav Havel, who had been jailed by the Communist regime in early 1989, was elected president of Czechoslovakia by acclamation of parliament at the end of December. The unemployed former shipyard worker from Gdañsk, Lech Wałęsa, became president of Poland the following year. The impact of these events had further repercussions. The draught of democracy began to blow into Yugoslavia which, though not part of the Communist bloc since 1948, had been suffering from a decade-long, apparently insurmountable, economic crisis. Communist leaders in Croatia and Slovenia called for democratic elections, thereby worsening their already fractious relations with Serbia. As each republic within Yugoslavia sought to maximize its autonomy and prosperity, the country descended within 18 months into the most violent conflict in Europe since World War II, in which perhaps a quarter of a million people died (see Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian War). Albania, which had also been outside the Soviet bloc, collapsed into anarchy, as the warlords of regional clans fought among themselves. V THE END OF THE USSR In the Soviet Union the loss of Eastern Europe emboldened both Gorbachev’s conservative opponents and his more radical challengers. Now nationalism began to dominate political debate in a country that had over 100 officially registered nationalities. Minorities demanded ever-greater autonomy, and were urged on by Gorbachev’s rival, Boris Yeltsin, who after being elected president of Russia in 1991 urged the localities to “seize as much sovereignty as you can handle”. Nationalist protests were especially vociferous in the Baltic States and the Caucasus. Some were led by local Communist leaders, but Gorbachev was neither prepared to expel opponents from the CPSU, nor to allow alternative parties to be formed. In turn, Russians became exasperated by the “ingratitude” of all the minorities for the sacrifices that the Russians had made to allow their economic development. However, Gorbachev was impeded from savage repression because the Baltic States had the highest standards of living in the country and so represented a kind of model for perestroika in the rest of the USSR. Also, the West had never recognized Soviet occupation of the Baltic States (a consequence of the NaziSoviet Pact), so a crackdown would have led to a diplomatic rupture. Faced with these conflicting pressures, Gorbachev sought a constitutional solution. He proposed a new Union Treaty that would grant localities much greater freedom from the centre. This was due to become law in late August 1991. Conservatives, however, believed that this would lead to the collapse of the Soviet Union and mounted a preemptive coup while Gorbachev was on holiday by the Black Sea. Yet they, too, lacked the nerve for brutal repression of the popular protests that followed, led by Yeltsin in front of the world’s cameras and supported by the West. Vital military and security forces refused to obey orders. The coup crumbled within a few days, but although Gorbachev was restored, these events had fatally weakened his prestige. On December 8 Yeltsin met the president of Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk, and the president of Belarus, Stanislau Shushkevich, in Minsk and they declared the end of the Soviet Union and its replacement by a Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The former Central Asian republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan were not invited but they subsequently forced their way into the CIS as “founding members”, along with Armenia, Moldova, and Azerbaijan (Georgia joined in 1993). VI THE AFTERMATH The end of the Cold War transformed world politics as well as the regimes themselves. All of them were plunged into the turmoil of democratic and economic change for which they were completely unprepared. Some states, such as Poland, were notably successful. Others, such as the former Yugoslavia, Georgia, and Tajikistan, were wracked by civil war, while Russia became embroiled in a debilitating conflict in Chechnya. Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia, albeit peacefully. All suffered economically at first, and most took nearly a decade to return to levels of economic activity that were roughly equivalent to pre-collapse levels. Partly for that reason some former Communists later won open elections, which would have been inconceivable before 1989 but which was also a sign of the success of the democratic transition and of the validity of the Communists’ claims to have become democrats. Other states, such as Belarus and the states of Central Asia, changed as little as possible. The collapse of Communism as the ruling ideology opened the way for nationalism to replace it. Territorial disputes erupted over boundaries both inside and between states. Pressure from outside, for example from the European Union and NATO, helped to restrain the excesses, but not always successfully, as the carnage in the former Yugoslavia demonstrated. The collapse of the Communist states also challenged communist parties outside Eastern Europe: the French Communist Party continued its decline, but the Italian Communist Party managed to rebrand itself as the Party of the Democratic Left and even led a centre-left coalition government for the first time in the mid-1990s. For most of the 1990s the Chinese Communist Party nervously sought to avoid the fate of the CPSU, while the regime in Cuba was forced to open up to unwanted and hasty economic changes as Soviet aid was withdrawn. Nor was communism the only ideology put in question. Socialism, too, was eclipsed. Various socialist and labour leaders cast around for a “third way” that might reconcile capitalism and socialism. More generally, the end of Communism was taken by people like the American analyst Francis Fukuyama to mark the “end of history” and the final victory of Western liberal capitalism. Eastern Europe once again became an integral part of a wider Europe. In Russia, too, some politicians talked of “a common European home”. NATO had to reinvent itself as conflict in Europe receded into the realm of the almost unthinkable, especially after countries in Eastern Europe and the Baltic States were offered membership. The European Union later entered into negotiations to expand to 25 members and beyond, most of the newcomers being former Communist states. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) was established to try to resolve conflicts arising from the collapse of the Communist states, but its remit reached Vladivostok. “Europe” had never before seemed to stretch to the borders of China and the Pacific. The end of the Cold War removed the great power competition that had exacerbated conflicts in the Third World in previous decades, especially in Africa. Former clients of the Soviet Union had to come to terms with the West. On the other hand it unglued some international disputes that had previously been frozen by nuclear stalemate. India and Pakistan both openly started developing nuclear weapons, thus setting up their own, much more fragile nuclear standoff. In the Middle East peace seemed as elusive as ever. International affairs appeared less predictable and more dangerous. Some commentators, such as Samuel P. Huntington even speculated about a possible future “clash of civilizations” on a global scale. It had been a truly historic two years. communism communism, fundamentally, a system of social organization in which property (especially real property and the means of production) is held in common. In modern usage, the term Communism (written with a capital C) is applied to the movement that aims to overthrow the capitalist order by revolutionary means and to establish a classless society in which all goods will be socially owned. The theories of the movement come from Karl Marx, as modified by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, leader of the successful Communist revolution in Russia. Communism, in this sense, is to be distinguished from socialism, which (as the term is commonly understood) seeks similar ends but by evolution rather than revolution. The Communist Manifesto The year 1848 was also marked by the appearance of The Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx andFriedrich Engels, the primary exposition of the socioeconomic doctrine that came to be known as Marxism. It postulated the inevitability of a communist society, which would result when economic forces (the determinants of history) caused the class war; in this struggle the exploited industrial proletariat would overthrow the capitalists and establish the new classless order of social ownership. Marxian theories and programs soon came to dominate left-wing thought. Although the German group (founded in 1847) for which The Communist Manifesto was written was called the Communist League, the Marxist movement went forward under the name of socialism; its 19th-century history is treated in the article under that heading and under Socialist parties, in European history. Cold War Years In World War II the USSR became an ally of the Western capitalist nations after Germany attacked it in 1941. As part of its cooperation with the Allies, the USSR brought about (1943) the dissolution of the Comintern. Hopes for continued cooperation, intrinsic in the formation of the United Nations, were dashed, however, by a widening rift between the Soviet bloc and the Western democracies, especially the United States, after the war. Communism had been vastly strengthened by the winning of many new nations into the zone of Soviet influence and strength in Eastern Europe. Governments strictly modeled on the Soviet Communist plan were installed in the “satellite” states—Albania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, and East Germany. A Communist government was also created under Marshal Tito in Yugoslavia, but Tito's independent policies led to the expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Cominform, which had replaced the Comintern, and Titoism was labeled deviationist. By 1950 the Chinese Communists held all of China except Taiwan, thus controlling the most populous nation in the world. A Communist administration was also installed in North Korea, and fighting between the People's Republic of Korea (Communist) and the southern Republic of Korea exploded in the Korean War (1950–53), fought between Communist and United Nations troops. Other areas where rising Communist strength provoked dissension and in some cases actual fighting include Malaya, Laos, many nations of the Middle East and Africa, and, especially, Vietnam, where the United States intervened to aid the South Vietnamese regime against Communist guerrillas and North Vietnam. In many of these poor countries, Communists attempted, with varying degrees of success, to unite with nationalist and socialist forces against Western imperialism. After the death of Stalin in 1953 some relaxation of Soviet Communist strictures seemed to occur, and at the 20th party congress (1956) Premier Nikita Khruschchev denounced the methods of Stalin and called for a return to the principles of Lenin, thus presaging some change in Communist methods, although none in fundamental ideology. A resurgence of nationalist feeling within the Soviet bloc—as was vividly demonstrated by the bloodily suppressed Hungarian uprising of 1956—ultimately had to be acknowledged by the USSR. However, while the USSR began to allow some limited freedom of action to the countries of Eastern Europe, the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 demonstrated its determination to prevent serious challenges to its domination. Ideological differences between China and the USSR became increasingly apparent in the 1960s and 70s, with China portraying itself as a leader of the underdeveloped world against the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, both the USSR and China sought better relations with the United States in the 1970s. The Collapse of Communism In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became leader of the Soviet Union and relaxed Communist strictures with the reform policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring). The Soviet Union did not intervene as the Soviet-bloc nations of Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary all abandoned dictatorial Communist rule by 1990. In 1991, driven by nationalistic ferver in many of the republics and a collapsing economy, the Soviet Union dissolved and Gorbachev resigned as president. Mikhail Gorbachev By the beginning of the 21st cent. traditional Communist party dictatorships held power only in China, Cuba, Laos, North Korea, and Vietnam. China, Laos, Vietnam, and, to a lesser degree, Cuba have reduced state control of the economy in order to stimulate growth. Although economic reform has been allowed in these countries, their Communist parties have proved unwilling to submit to popular democratic movements; in 1989 the Chinese government brutally crushed student demonstrations in Beijing's Tiananmen Square. Communist parties, or their descendent parties, remain politically important in many Eastern European nations and in Russia and many of the other nations that emerged from the former Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union will produce 50 million tons of pig iron, 60 million tons of steel, 500 million tons of coal, and 60 million tons of oil we will be guaranteed against any misfortune. Stalin, Speech in February 19461 The contradiction which became apparent in the 1950s, between the development of the production forces and the growing needs of society on the one hand, and the increasingly obsolete productive relations of the old system of economic management on the other hand, became sharper with every year. The conservative structure of the economy and the tendencies for extensive investment, together with the backward system of economic management gradually turned into a brake and an obstacle to the economic and social development of the country. Abel Aganbegyan, The Economic Challenge of Perestroika, p. 49 The world economy is a single organism, and no state, whatever its social system or economic status, can normally develop outside it. This places on the agenda the need to devise a fundamentally new machinery for the functioning of the world economy, a new structure of the international division of labor. At the same time, the growth of the world economy reveals the contradictions and limits inherent in the traditional type of industrialization. Mikhail Gorbachev, Address to the United Nations, 19882 We will realize one day that we are in fact the only country on Earth that tries to enter the twenty-first century with the obsolete ideology of the nineteenth century. Boris Yeltsin, Memoirs, 1990, p. 2453 The collapse of Communism: Where did Marxism fail? In the collapse of communism, one may ask, "Where did Marxism fail?" Let print the definition of communism. According to "The World Book Dictionary Thorndike Barnhart, it is a system in which most or all property is owned by the state and is supposed to be shared by all. Communism comes from a philosophy based on the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the 1800's and seeks the overthrow of non communist societies in behalf of the labouring class, usually as the result of a series of struggle of class conflict. Now, let try to print the meaning of Marxism. According to "The World Book Dictionary Thorndike Barnhart, it is the political and economic theories of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. They interpreted history as a continuing economic class struggle and believed that the eventual result would be the Establishment of a classless society and communal ownership of all natural and industrial resources. Marxism failed because: 1. Karl Marx's communist manifesto is complex and hard to understand by the workers, in which is his primary force in carrying his class struggle. Karl Marx was a known philosopher during his time and when he wrote this communist manifesto and was introduced to the working class it could have been hard for them to match his level of understanding, hence the worker's political attachment to the communist manifesto was weak and in the process loosen up. Since communism is plainly theoretical and capitalism is a one political and economic system in place, Karl Marx's working class evidently was in a path of division. There were those that had no choice but to patronise and subscribe to capitalism, leaving the rest of the working class to be loyal and true believers to the principles as laid down by Karl Marx, but the remaining force wasn't enough to meet the demand by the theoretical presentation of class struggle for the working class to sustain any of their victories initially won. Until now the difficulty in understanding the core of communist manifesto evidently is a contributing factor in serving its own weakness to rally in uniting the worker's of the world to carry out the socialist's revolution in overthrowing the class system. The concept of class struggle is just so vague, it is just not an easy one for a worker to have it easily understood as Karl Marx easily does. The communist manifesto must have failed to communicate effectively with the working class as Karl Marx would politically desire to wish for. 2. Karl Marx laid down the face of the political and economic future, which is the primitive communal going from one stage to another until communism is achieved. To me, short after Karl Marx has laid down his theory that the working class will overthrow the class system and establish a communist classless society, is a gross mistake for Karl Marx , for I believe that no one and no one and that includes Karl Marx can and should lay down any political and economic face of the future. The future cannot be tailor made. The formations of any future political and economic situations are only shaped from an accessible visible time and or as it come on hand, coming from the different players involved. No one sees the future, so therefore no one can write it down, however Karl Marx wrote it down the downfall of capitalism, the establishment of socialism then the formation of a classless society under communism. No one formulates and lays down the political and economic path for people to toe and expect it to actually materialise accordingly. For one to do that would lead to a gross violation of individual's historical involvement in shaping up the unknown political and economic face of Man's future. No one would want to toe a path leading to a ready laid down future. 3. Marxism was published. In the process this became a reading book. As of today, in the observation of the Internet climate, Karl Marx's works and writings have become common products in a free enterprise market that suits capitalist's exploitation. To me the moment a thought, theory and principle with its political and economic purpose which aims in shaping up and laying down a face of a far away future, is published, there is this greater chance of a self defeat in the whole process of its own struggle. When Marxism, as a theory was published, its followers and believers simply became dogmatic in pursuing the victory of class struggle. The society is a constant moving relationship between capital and labour. The application of pure Marxism could prove a gross mistake for it failed to adjust accordingly with the continuing face and fast phase of global wide aspects of industries. Marxism is out of date. Marxism is obsolete. Consider these: Which one are you? If you happen to stay with the past you are just a plain "Catcher". If you happen to stay with the present time you are just a plain "Copier". But if you stay focus with the future there is a strong chance and possibility that you could produce the "Prime and Original Thoughts". The fall of Communism 20 years since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc The year 1989 turned out to be the most significant year in European history since World War II. Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania and East Germany became free to determine their own futures after years of Communist rule. The twelve months that shook Europe were preceded by decades of totalitarianism and periodic struggles for independence, which prior to 1989 always ended in tragedy - the Soviet army intervention in Hungary in 1956, the Warsaw Pact army invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and the introduction of the martial law in Poland in 1981. The 1989 collapse of the Communist Bloc stems from the Polish Round Table Talks (February-April 1989), at which the government negotiated with the then-banned trade union Solidarity for the first time in an attempt to diffuse growing social unrest. This resulted in the first partially free elections in a Communist country on 4 June and a new government headed by a non-communist prime minister and including opposition members. The collapse of Communism in Hungary took a similar path, with the transition to democracy taking place via negotiations with reform activists. Hungary further weakened the Communist bloc by opening its border with Austria, allowing thousands of East Germans to escape to the West. In October 1989 German Democratic Republic celebrated its 40th anniversary and just a few weeks later, on 9th November the Berlin Wall fell. As well as marking the beginning of German reunification, this event is seen as by many as the symbolic end of Communism in Europe. Bulgarian leader Todor Zhivkov was ousted the day after the wall fell, and even though his place was taken by a Communist movement veteran, this event gave impetus to the country’s pro-democracy movement. On 17th November protests in Prague began, bringing the Czech opposition to power the following month. The bloodiest events took place in Romania. In the second half of December the people of Timişoara and later Bucharest began to protest against the hated dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu. At first the protests were severely suppressed, but the army eventually refused to fire on civilians and turned against Ceauşescu. His execution on Christmas Day marked the end of Communism in Romania. The events of 1989 were just a start of the changes facing the countries of Central and Eastern Europe countries in the transition away from Communism. The biggest issues were the lack of technological development and the economic crises caused by decades of a centrally planned economy. Finding themselves at the sharp end of these economic problems, the populations began to waver in their support for reform, making it possible for former Communists to take back the reins in some countries. A great deal has changed in Europe in the 20 years since Communism collapsed. The independence of former Soviet Bloc countries was a catalyst for the development of European relations and triggered the dissolution of Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in the years that followed. The accession of Central and Eastern Europe countries to the European Union has boosted their economic development. The societies themselves have become increasingly willing to participate in creating the European community. Yet just 20 years ago today’s European free market and civil liberties were just a dream for the countries of the Communist Bloc. Annus Mirabilis: The Collapse of Communism in Soviet Bloc The Annus Mirabilis of people in the Soviet Bloc must be 1989. They were liberated from oppressive communist regimes as they collapsed one by one. One needs to consider several internal and external factors which played roles in leading communism toward its end. Internal factors included the presence of anti-communist resistance, the desire to join Europe and the absence of obstacles to transition toward democracy and market economy. Anti-communist resistances had been most vivid in Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia. They were not willing to be communist states; instead, communism in there was imposed by Soviet occupation forces. Hungary even had its own reasonably free and fair elections in 1945 before Hungarian Communist party used salami tactic and fake votes to seize power in 1947. Hungarians showed their detestation to communism in their 1956 revolution while Czechs did the same twelve years later in what was called Prague Spring. Both of these events incited Soviet brutal responses. Polish workers in Lenin shipyard in Gdansk took a softer way to fight for their rights by creating independent free trade union, Solidarity, which brought Lech Walesa to prominence. The fact that communism was even opposed by workers, the backbone of its economy system, in those countries created wound which Soviet could never recover from. Geza Jeszensky, former Prime Minister of Hungary, argued that the most effective weapon of the West in the Cold War was prosperity and its consumer goods. Entering 1980s, countries affiliated with Soviet Bloc already experienced declining output, huge foreign debt and foods shortage. In short, socialism was in crisis. It was to prove that communism contained seeds of its own destruction and brought nothing but misery that Hungary and Poland led other communist states in 1980s to press for the end of communism and rejoin economicallypromising Western Europe. Furthermore, transition toward democracy and market economy basically did not face serious challenge from both society and the members of Communist Party. Janos Kornai, leading researcher of political economy of communism, mentioned that peaceful transition differentiated democratization in Central Eastern Europe from it in other places. It was mainly because there was no clash of ideas between society and party officials since both of favored them the transition. People in communist states were tired of living an impoverished live under oppressive dictatorship and they knew exactly that people living hundreds of kilometers westward were having luxurious and joyous life. Implementation of democracy may let them have voices over policies that influencing them and introduction of market economy, which also featured privatization, was expected to break up hegemonic state power and build new middle class. Meanwhile, party officials themselves were very interested to engineer the collapse of communism. As Poznanski argued, party officials knew exactly well that they could convert their political power to economy power through privatization by becoming the owner of exstate owned enterprises themselves. As a bonus, they could avoid the imprisonment for siding with the will of the people. As evidenced vividly in Russia in 1990s, ex-party officials bought those enterprises with outrageously cheap prices and corrupted massive amount of money in the process itself, ultimately proving that moral decay was the inevitable legacy of communism. Talking about the collapse of communism, one shall not forget the role played by external factors, such as the elevation of Cardinal Karol Wojtyla to papacy and the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev to power in Soviet Union. Polish has always been religious. Persecution of churches in communist states failed to blockade the influence of Catholic churches to the society. Karol Wojtyla was the first Polish to be elected as Pope and his several visits to Poland brought bliss and reunited the people against communism. However, while Wojtyla’s role was limited to Polish society, Mikhail Gorbachev was the real actor, regardless of his intention, who led the communism to its end. Soviet Union was in the exorbitant arms race with Ronald Reagan’s America. It also started to face problem in controlling its oversized periphery, ranging from Cuba, Nicaragua and Afghanistan to Angola, countries which economically contributed nothing but diminishing budget to Soviet Union. He believed in the virtue of communism and wanted to reform badly performing existing system. However, his policies of Glasnost, Perestroika and releasing of political prisoners proved to be disastrous for communist regimes. He even floated Brezhnev doctrine, which was basically the same with Western domino theory, by implicitly said no to military intervention and allowed other communist countries to pursue their own way. He eliminated some parts and made the later-founded Janos Kornai’s theory of classical socialist system not coherent anymore. Kornai argued that communism would only work if there were state ideology, one party dictatorship, state ownership and bureaucratic coordination of allocations of resources. Nevertheless, he became the role model of non-Soviet communists who eventually started implementing same reformist agenda like him. It was too much for Czechs, Romanians and Bulgarians to see how Hungary and Poland could move further and further away from communism. Brezhnev doctrine proved to be right, communist regimes fell one by one in tremendous speed. Gorbachev might never foresee that the outcome of his reformist policies would be catastrophic for the regimes. If there is someone to blame for the collapse of communism, he is that person. In one occasion, Henry Kissinger told Vladimir Putin that he did not understand why Gorbachev abandoned Eastern Europe and Putin, though surprised to hear such things from former American Secretary of State, was pretty much agree with him and believed Soviet could have avoided all the problems should it did not exist Eastern Europe hastily. I would rather say that Soviet’s exit from Eastern Europe was mere result of Gorbachev’s Glasnost and Perestroika policies. What was, thus, the reason to continuously and blindly pursue the bound-to-be-failed communism if your leader himself started diverting from it? This kind of confusion altogether with other factors mentioned briefly above culminated in the downfall of communism