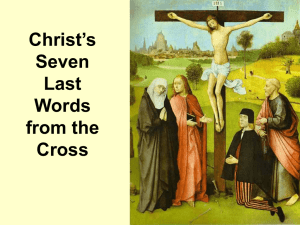

New testament accounts.

advertisement