The Underground Railroad Meets the Mississippi

advertisement

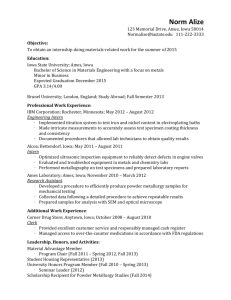

The Iowa Underground Railroad and “Old” John Brown: Iowa’s Role in the Antislavery Movement In the 1850s, the United States was in the midst of a period of economic expansion. New industries appeared throughout the North. Agriculture grew, as farmers began to settle the rich lands of the Upper Midwest, and the “Cotton Kingdom” expanded into Arkansas and Texas. All of this growth was accelerated by a transportation revolution that saw an expansion of steamship lines and railroad companies. Unfortunately, as the nation expanded economically and geographically, the growing controversy over slavery threatened to tear it apart politically. As the United States entered the 1850s, the remaining unsettled regions of the TransAppalachian West were rapidly filling. In the North, railroads reached across the Mississippi, connecting the rich farmlands of Iowa and the rest of the Midwest with the growing and increasingly industrialized urban areas of the Northeast. To a lesser extent, east-west lines also appeared in the South. More often, southern rail lines were relatively short, connecting agricultural regions with the great rivers that still constituted the main commercial arteries of the South. Along these rivers, staple crops, especially cotton, were transported to coastal ports for shipment to faraway markets in England and New England. By the 1850s, the North and the South had developed separate economies. In the North, industry and commercial agriculture were the twin pillars of economic prosperity. In the South, cotton was king. As the North and the South developed separate economies, they also developed separate societies. At the heart of the matter was slavery. The southern economic system depended on it. Slaves were more valuable to southern planters than even the land itself. As the South became dependent on cotton and slavery, a growing antislavery movement began to gain momentum in the North. Inspired by editors like William Lloyd Garrison and ministers like 1 Lyman Beecher and Theodore Weld, the movement grew from a few small societies in Pennsylvania and New England in the 1820s to a regional movement that spread throughout the North and Midwest by the 1830s. The American Antislavery Society was founded in 1832. By 1835, there were approximately 400 chapters; by 1838, there were 1,350 chapters with more than 250,000 members. By the mid-1840s, there was even a thriving antislavery society in Johnson County on the distant Iowa frontier. The “underground railroad” was an important offshoot of the antislavery movement. The “underground railroad” was an organized system for helping escaped slaves from the southern states to reach freedom in the North or in Canada in the years before the Civil War. The name may have come from an incident in 1831 when a slave named Tice David ran away from a Kentucky plantation. His master followed him to the banks of the Ohio River, but lost track of him when he dived into the water and swam across to Ripley, Ohio. Returning home emptyhanded, Tice’s owner told everyone that the slave “must have escaped on an underground road.” Steam railroads were a new and exciting means of travel in 1831. Maybe that’s why the “underground road” became an “underground railroad.” Those who kept safe houses for runaways were called “station agents.” Others who guided fugitive slaves from one place to another became “conductors.” The fugitive slaves themselves were referred to as “passengers.” In the 1800s, only a very small percentage of Iowa’s population was African-American. However, when Iowa entered the Union in 1846, the state quickly allied itself with the “free” states in the escalating tensions of the pre-Civil War years. Many Iowans were fierce abolitionists who helped establish several branches of the Underground Railroad in the state. Various religious groups, including Quakers, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Methodists, were involved as conductors in the Underground Railroad movement. John Todd of Tabor, 2 James C. Jordan of Des Moines, Josiah B. Grinnell of Grinnell, Anna and John Cook of Earlham, John Williamson, a free African American living near Council Bluffs, and many others offered “safe havens” to runaway slaves. Although they realized that they were breaking the laws established by the Fugitive Slave Act, abolitionists felt they were following “God’s law” by helping freedom seekers (runaway slaves). In Iowa City, two prominent antislavery men, Dr. Jesse Bowen and William Penn Clarke, a prominent newspaper editor and lawyer, aided the famous abolitionist fighter, John Brown, in his efforts to supply pro-free state forces in the Kansas Territory with rifles, ammunition, and supplies. Amidst the growing tensions of the 1850s, the new state of Iowa experienced remarkable growth. In late December 1855, the Mississippi-Missouri Railroad Company completed a line from Davenport to Iowa City. The arrival of the railroad spurred economic growth and helped to offset the loss of the capital city to Des Moines in 1857. By the eve of the Civil War (1861), Iowa City’s population had reached approximately 4,000. As settlement in Iowa increased, the Iowa branches of the Underground Railroad became somewhat better organized. Most traversed the southern half of the state from the Missouri River in the West to the Mississippi River in the East. Along the way, these main branches connected with other routes coming north out of Missouri. Along these routes, hundreds of fugitive slaves made their way to freedom. It is impossible to know the exact number who may have escaped, either through Iowa or nationwide. However, one historian estimates the number of successful escapes at around 35,000. There were 4 million slaves in the South before 1860. The Underground Railroad was a serious annoyance to slaveholders, but it didn’t make much of a difference in the number of slaves held. 3 John Brown was a famous conductor on the Underground Railroad. From 1856 to 1859, Brown visited Iowa City and the Quaker settlements of Cedar County, including Pedee, Springdale, and West Liberty, several times. Brown often visited prominent men in Iowa City, including Dr. Jesse Bowen and William Penn Clarke. Brown frequently received donations to aid his efforts to make Kansas a free state. On his journeys through Iowa, Brown often brought fugitive slaves with him. Most of these escaped slaves came from Missouri. During his 1858 and 1859 visits to Johnson and Cedar Counties, Brown began to train a band of abolitionist firebrands for a planned attack on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown hoped to use weapons from the arsenal to arm slaves in what he hoped would be a large-scale rebellion. Brown also recruited several local citizens for his “army,” including Edwin and Barclay Coppock, George B. Gill, and Stewart Taylor. The Coppock brothers and Taylor accompanied Brown to Harpers Ferry, along with another Iowan, Jeremiah G. Anderson of Kossuth. Brown returned to Iowa City for the last time in February 1859, accompanied by 12 runaway slaves, having already passed through several Iowa “stations” on the Underground Railroad, including Tabor, Des Moines, and Grinnell. Several local antislavery men, including Hiram Price and William Penn Clarke, developed an elaborate scheme to assist Brown in securing a boxcar on a train owned by the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad. In late February, a small crowd of supporters cheered the escape of Brown, his men, and the fugitive slaves, as they left the depot in West Liberty and headed for Chicago. Brown’s departure came none too soon, as a group of local anti-abolitionists, including George Boatham, were organizing an effort to apprehend Brown and gain the $3,000 reward offered for his capture. 4 Later in 1859, a local group of Brown supporters, including John Painter of Springdale, shipped 196 Sharp’s rifles and 196 Sharp’s revolvers by rail (once again on the Mississippi and Missouri line) to Harpers Ferry. This cargo was transported in crates labeled “carpenters’ tools.” Some of these “tools” were used in Brown’s famous and failed attack on October 16, 1859. John Brown gained eternal fame at Harpers Ferry. He seized the federal arsenal, killing seven people (including a free black), and injuring ten more. He intended to arm slaves with weapons from the arsenal, but the attack failed. Within 36 hours, Brown and sixteen of his men were either killed or captured by local farmers, militiamen, and United States Marines led by Army Col. Robert E. Lee. Brown’s subsequent trial for treason by the state of Virginia and his execution by hanging captured the nation’s attention. Many in the North hailed him as a heroic martyr, while throughout the South, he was vilified as an evil terrorist. The praise Brown received throughout the North is an indicator of the growing strength of antislavery sentiment in that region. As abolitionists became more assertive, southerners became more defensive. Southerners defended and even praised slavery in numerous articles in regional journals like DeBow’s Review. Following the Mexican War, the United States faced a series of escalating disputes over the question of the extension of slavery into the western territories. The Whig Party foundered over the issue and was replaced, in the North, by the Republican Party, whose central principle was opposition to any further extension of slavery. During the 1850s, the bonds of unity between the North and the South began to dissolve. Religious denominations split over the question of slavery. In particular, John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and the wave of support he received from many in the North alarmed southerners and made many question the wisdom of remaining in the Union. Finally, the Democratic Party 5 broke apart in 1860, opening the way for the election of Abraham Lincoln, the secession of 11 slave states, and the beginning of a tragic civil war. 6 BIBLIOGRAPHY Brinkley, Alan. American History: A Survey. Boston, Massachusetts: McGraw-Hill, 1999. Berrier, G. Galin. “The Underground Railroad in Iowa,” in Outside In: African American History in Iowa. Des Moines, Iowa: State Historical Society of Iowa, 2000. History of Johnson County, Iowa: 1836-1882. Portland, Indiana: Modern Pre-Binding Corporation, 1883. The Palimpsest, Vol. II, No. 5 (May 1921). The Palimpsest, Vol. VII, No. 3 (March 1926). Rohrbough, Malcom. The Trans-Appalachian Frontier – People, Societies, and Institutions, 1775-1850. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. Thompson, William H. Transportation in Iowa: A Historical Summary. Iowa Department of Transportation, 1989. 7 Maps and Photos for Iowa Underground Railroad Exhibit Maps: “Iowa Routes on the National Underground Railroad” (Data for this map was provided by John Zeller, a historian for the Iowa Freedom Trail Program and the State Historical Society of Iowa.) “Iowa’s Underground Railroad Network” (from “The Iowa Underground Railroad,” by Curt Harnack in The Iowan, June-July 1956, pages 20-21) Photos: (Note: All photos taken before 1923 are part of the public domain. I believe the same is true for all photos and illustrations shown on National Park Service websites, unless otherwise indicated.) 1 – John Brown in 1859 (source – Wikipedia) 2 – Josiah B. Grinnell (source – Wikipedia) 3 – Todd House in Tabor, Iowa (National Park Service) 4 – Hitchcock House in Lewis, Iowa (National Park Service) 5 – Henderson Lewelling House in Salem, Iowa (National Park Service) 6 – Jordan House in West Des Moines, Iowa (National Park Service) 7 – Photo of Iowa State Senator James C. Jordan (National Park Service) 8 – U. S. Marines storming John Brown’s “fort” at Harpers Ferry (National Park Service) 9 - Black visitors at Harpers Ferry in 1896 (National Park Service) 10 – John Brown’s Fort in 1995 (National Park Service) Websites: The Underground Railroad in Iowa (www.iowan.com/underground_railroad_jf2005.cfm) Harpers Ferry National Park (www.nps.gov/hafe/photosmultiamedia) 8 9