HIST 105: Western Civilization I

advertisement

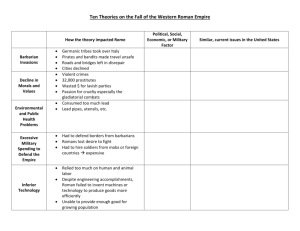

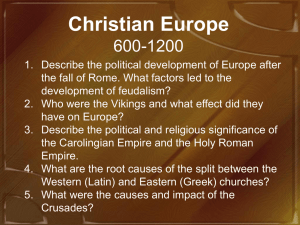

HIST 20: World History, I The European Middle Ages, I: Fragmentation, Centralization, and the Church (Notes) I. Background: “Two Births” Here’s a re-cap of the events surrounding the collapse of the Western Roman Empire: o In an attempt to stop the decline of the empire and address the crises of the third century, Diocletian (284-305) divided the Roman Empire into two sections, east and west, each headed by a “partner” under the rule of the emperor. Constantine then shifted the center of the empire to the east, to the new city of Constantinople, which he declared the “new Rome” in 330. With the shift in capital came a shift in the wealth, administrative order, and the overall cohesion of the western part of the empire. o At the same time, the borders of the empire (particularly in the west) were under “attack” by “barbarian” tribes, most of which wanted to enjoy the benefits of the empire, and who coexisted (almost) peacefully with Rome. Nevertheless, the empire could not meet demands of the “barbarians”, especially when significant numbers of tribes were pushed further west by the Huns. In view of the empire’s seeming unwillingness to accommodate/protect them, the Visigoths revolted, ultimately defeating the Roman army in the Battle of Adrianople (378) and sacking Rome in 410. The sack was made possible, then, by the empire’s overextension: its defenses were physically weakened, the people were overtaxed, famine and pestilence overran the empire, and political chaos reigned. o In the late 4th and early 5th centuries, there were further invasions in the west, and in 455 Rome was sacked again, this time by the Vandals. The western half of the empire was unable to recuperate from this second sack, and in 467, when Romulus Augustus is deposed by Odovacar, the west “falls”. o Although later emperors attempted to reunite the empire, particularly Justinian in 527-565, the west had devolved into a series of independent pockets of power, unified solely by the universality and organization of Christianity, as we shall see. Justinian’s failed attempts to reunification mark the final break between east and west, and the rise of the Eastern Roman Empire as the Byzantine Empire. o You must keep in mind that the military triumph of the Germanic tribes was not necessarily the end of the empire in cultural terms. Although much changed with the introduction of Germanic law and political organization, the bases for European realities remained Latin, Roman law, ancient philosophy and, most importantly, Christianity as it was first defined within the empire. Justinian’s efforts to re-unite the empire ultimately failed in the 600s. A major cause of the failure of Byzantium (as the Eastern Roman Empire, which survived until 1453, came to be known) came from the rise of a new religion, Islam, whose rapid spread overtaxed the Empire’s resources. The Muslim advance was only stopped in 732 by the forces of Frankish king Charles Martel (more on him below). There is an additional development that I should introduce here, the process of deurbanization (the moving out of cities) in the west. This was a process that began already under the Empire, in the 400s. Roman elites began to move to the countryside and formed large landed estates for a variety of reasons, one the most important being economic: the fiscal burden of the Roman state rose greatly during the period of the late Empire and, during that time of increasing chaos, the possession of land emerged as one of the most secure investments. The process of deurbanization would continue over the next several centuries. It had several major results: 1. cities in what had been the Western Empire shrunk in size 2. the elite of the region became transformed from an urban into a rural elite. In brief, by the 600s, the west, which had always been always less urbanized than the east, became predominately rural. Indeed, for centuries afterwards, on average, around 90% of the population would live in the country, and only 9% in cities. The decline of cities, which had been central to the functioning of the Roman Empire, also meant that central administration largely disappeared. Because of these various processes, then, by the mid-700s, the people of what had been the Western Roman Empire, were politically and socially different from the east. More importantly, as their use of the term “Saracen” (Easterner) to refer to Muslims indicates, they mentally saw themselves as distinct and disconnected from the lands and peoples of the eastern Mediterranean. This was a huge development. This cultural conception of difference marks the destruction of what had been, under the Romans, a united whole. The West, with that capital “w,” and the idea of the European continent as a place and people unlike Africa, Asia, or the East, had been born. We have, as well, a second “birth” – that of a new historical period. We have finally left the ancient world, and have entered the medieval era, or the Middle Ages, a thousand year period, lasting from approximately 500 through around 1500. The Middle Ages were heavily influenced by three inherited cultural traditions: those of ancient Greece and Rome, the barbarians, and Christianity. It is important to note that for a long time the term “Middle Ages” was used in a pejorative (negative) sense, as a period of darkness and barbarity between the world of Rome and the time of the Renaissance, a time we will talk about Tuesday. This prejudice obscures the continuities from the Roman period and the real advancements medieval people made. However, people of the time also saw themselves as living in the Middle Ages, but they meant the term in a Christian sense, as the period between Jesus Christ’s ascension into heaven forty days after the resurrection, and the Apocalypse, when Christ would return to judge the living and the dead, and the world would be destroyed. II. The Church and Medieval Christianity As we saw, during the 400s, the Church in the west began developing in ways different from the Church in the east: 1. The Church in the west after it became legitimate began to evolve along secular, Roman, lines (Bishops as leaders of dioceses, etc.) 2. Remember, because there was only one Patriarch in the west, the Church there was much more unified than in the east 3. Also, recall that in the 450s, it was the Patriarch, not the Emperor, who prevented the Huns from sacking Rome. The Church gained an important secular as well as spiritual role. 4. After the collapse of imperial authority in 476, the Church began to fill the resulting administrative vacuum. Since the Church had been structured to mirror the imperial bureaucracy, and many of its members were originally Roman bureaucrats, the Church became a main center of order in the west. For example, Church courts became the main source of secular as well as spiritual justice for centuries. 5. For the next thousand years, the main bond joining together the peoples of the west was the Christian religion. In a sign of this identification, the people of the west began to call their region “Christendom.” A. The Rise of the Papacy One crucial development, which us brings us back to the sense of east versus west, is that, during the early Middle Ages, the united Christian Church also divided along these geographical lines. In short, during this period, the Papacy in Rome emerged as the supreme spiritual authority (versus merely being merely the seat of one of five patriarchs). This was a long-term development: 1. To repeat, following the collapse of the western Empire, the Church in the west was in a position of greater independence. 2. As we saw, early on, the Church engaged in a political alliance which gave secular power behind its spiritual authority. This was the conversion of Clovis, King of the Franks, in c. 496. This alliance would bear great fruit two and a half centuries later. 3. One implication of the rise of Islam (632-732) was the regained independence of the Patriarch of Rome from the direct control of the Emperors in Constantinople. 4. A major moment in the rise of the Papacy came in the 750s. In 754 Patriarch Stephen became the first Roman patriarch to leave the Italian peninsula, to meet with Peppin, King of the Franks, grandson of Charles Martel, the King who had defeated the Muslims in 732. Peppin was seeking Church sanction to his recent takeover of the Frankish throne. Stephen needed protection against a violent tribe, the Lombards, who had recently invaded Italy. Stephen reconsecrated Peppin, anointed him with holy oil, gave Peppin his blessing to rule in perpetuity and granted the King the title of “patrician of the Romans. What was a major change was the fact that the Patriarch, not the Emperor, was granting an imperial title. 5. In 756, Peppin came into northern Italy and destroyed the Lombards. Once more, a huge event with deep implications, occurred. One territory the Lombards had taken over was a region of north-eastern Italy known as the Excharate of Ravenna. Under the Byzantine reconquest, this was the administrative capital of the peninsula. After Peppin had taken over Ravenna, one would have expected him to return it to its official ruler, the Emperor. However, the Frankish king granted it instead to Stephen. The Patriarch gladly accepted the donation. This had two important implications: 1) the Patriarchs became secular rulers in Italy (they ruled a swath of land across Italy known as the Papal States); 2) Stephen’s actions were a clear defiance of the supreme authority of the Emperors in Constantinople. It was after this that the Patriarchs began to call themselves Popes, and claimed equal, and implied greater, spiritual authority with the Emperor. 6. Three hundred years later, in 1054, the split between eastern and western Christianity became official in what is known as the “Great Schism.” This split endures to this day. B. The Nature of Medieval Christianity Let us step back from the narrative for a second, and discuss medieval Christianity in a more thematic manner. Medieval Christianity can be called an institutionalized belief system, in than religious practices and beliefs were intrinsically bound to the institution which administered them. Remember, the institution emerged from the early movement conducted by Jesus’s followers—it derived its spiritual authority from this connection to Jesus The institution of the Church was an integral part of Christian belief—this structure, over 1500 years old, was seen as necessary for salvation— The Church claimed to be the “living word” of God—in that the Bible is not the only source of knowledge about faith—God continues to reveal himself to man through the Church which, guided by the Holy Spirit, acts as the interpreter between God and man—hence the Church came to be at the top of the social hierarchy (as we shall discuss in the PowerPoint lecture). Three Aspects of the Church c. (around) 1500: 1. Social Role: • The Church played a huge role in European society c. 1500—remember the Church was a supra-national institution, in that it bound Europe into a common culture— think “Christendom.” • By 1500 the institution of the Church was enmeshed in almost every aspect of daily life, down to the most mundane level • Some Examples: a. In the Middle Ages, TIME organized around Christian beliefs—the idea was that no time stood apart from God: The week was geared towards Sunday—a day dedicated to God and rest; the year revolved around the life of Jesus—the holiest part of the year being the period right before Christmas in the winter (Jesus’s birth) to right after Easter in the Spring (Jesus’s resurrection) b. The Medieval Church was in charge of social welfare—for example, feeding the poor, sheltering the homeless, caring for the sick—these things NOT done by secular governments c. These actions aided by Church teachings on Good Works (see below) 2. Beliefs and Practices: Beliefs: The Church argued that in order to achieve salvation, Christians had to practice an “active faith”—you could not get to heaven just by faith alone—Satan understood faith—this was called “dead faith”—instead one had to play an active part in one’s own salvation—express faith through concrete actions 2 major actions called for: 1. Participation in Holy Rituals mediated by the Church: a. The most important and most common—weekly Mass on Sunday— ritual reenactment of Jesus’s sacrifice—most important part of Mass = communion, Eucharist—when God, through the priest changes bread and wine into the actual body and blood of Jesus—transubstantiation b. The Seven Sacraments—baptism, penance, communion (Eucharist), matrimony, holy orders, anointing of the sick—ritually mark major moments of life—all are mediated through the priesthood—the 2 most important and the only ones repeated = penance and communion 2. Performance of “Good Works”: Included giving money to the Church—giving alms to the poor (Social Welfare); visiting the sick—In Brief = doing good deeds for others was “active faith”—ensuring own salvation Practices: • Marked by great diversity— the Church’s message was adaptable; it made itself fit the needs of different groups in society • Greatest Example: The Cult of The Saints— saints are dead Christians who are in heaven and, therefore, close to God— it was believed that the dead were still part of the Christian community and therefore one could communicate with them through prayer— different saints became the “patrons” of different bodies within society—saint Nicolas, for example, was the patron saint of thieves • An IMPORTANT CHARACTERISTIC OF PRACTICE was its extensive use of images and material relics to convey religious teachings. Remember, this is an ILLITERATE SOCIETY—this emphasis on the visual in particular, and the senses in general, remains an important element of Catholic culture 3. Structure • Hierarchical: The Pope o This is the name given to the bishop of Rome III. o He continues role of Saint Peter (i.e. he is selected by God to lead His Church) o That means that papal actions are supposed to be motivated by the Holy Spirit and, therefore, infallible (never wrong) The Clergy o divided into 2 types: o Secular Clergy—“those in the world” • Bishops are those members in spiritual charge of a diocese (a distinct territory) • Priests are those in charge of local parishes (where most people interact with the Church) o Regular Clergy—“Those who follow a set of Rules” (monks and nuns) • monastic orders NOT limited by territorial limits •There are lots of different types of orders—some remove themselves from active life, others don’t • monasteries and convents widespread throughout Europe Empire Reborn: The Rise and Fall of the Carolingians Now let us return to our political narrative. In theory, up to the reign of Justinian the whole empire was unified under the eastern emperor. Germanic rulers (generally known as kings) were supposedly viceroys working under the authority of the emperor, who remained in Constantinople. In practice, however, this was not the case. Germanic kings had, for the most part, two things which kept them apart from real imperial unification: 1. Westerners did not want the return of Roman taxation, Roman justice, and imperial interference in their affairs. 2. Many Germanic tribes, although they had converted early on to Christianity, converted to a particular kind of Christianity known as Arianism. Very roughly, Arians were followers of a priest names Arius, who held that Jesus was only a human being endowed with divine powers, and not “God the Son,” one with and identical to both the Father and the Holy Spirit. They were atill considered Christian because they embraced Jesus as a divine prophet, and thus as the only way to God. However, the issue is that the empire followed instead the official, Roman kind of Christianity that embraced Christ’s divinity. Their religious differences translated into yet another reason to reject imperial reunification. There were two “Western” (read non-Roman) attempts to recreate an empire. Both were by kings of the Germanic tribe of the Franks, which originally settled into the area f modern-day Belgium (northwest of France), but ultimately came to rule over what is today Holland, Belgium, France, Switzerland, and Germany. 1. The first attempt was by King Clovis (c. 466-511). Clovis was a warrior chieftain, who unifies many of the Frankish tribes. He created the first ruling family of the Franks, the Merovingians. During his reign, Clovis was able to also defeat the Burgundian and Visigothic tribes, and subsumed them under the Kingdom of the Franks. Clovis attempted to centralize his power by creating “pacts” of mutual service between himself and lesser warriors who could, nevertheless, help him pacify his territory. In fact, Clovis was the first to implement the system known as feudalism (about which, more below). However, Clovis’s plan back-fired, because the men who were supposed to help him organize and rule (known as counts) instead took more and more power upon themselves. By the 7th century, the Merovingian kings were kings in name only. Instead, real power has held by the “mayor of the palace,” the court representative and spokesperson of the counts. 2. It is through their role as mayors that another family was able to grasp power for themselves. With the help of the Patriarch of Rome (nowadays known as the Pope), the Carolingians rose to power in 751. The Carolingians pledged to convert all peoples from the Arian heresy to Roman Christianity, and the pope pledged to back the new kings, particularly by officially claiming that the Carolingians had been chosen by God to defend Christianity. It has been said that it was during the reign of Charlemagne (742-814) that the transition from classical to early medieval civilization was completed. He came to the throne of the Frankish kingdom in 771 and it was during his reign that a new civilization -- a European civilization -- came into existence. If anything characterizes Charlemagne's rule it was stability. His reign was based on harmony which developed between three elements: the Roman past, the Germanic way of life, and Christianity. Charlemagne devoted his entire reign to blending these three elements into one kingdom and thus secured the foundation upon which European society would develop. Charlemagne implemented two policies: a) The first policy was one of expansion. Charlemagne's goal was to unite all Germanic people into one kingdom. b) The second policy was religious in that Charlemagne wanted to convert all of the Frankish kingdom, and those lands he conquered, to Christianity. In fact, in this he was helped by the pope, who crowned him “Holy Roman Emperor” in 800. This marked a definite break (at least in theory), both for politics and for the Church, from imperial influence. These two policies meant that Charlemagne's reign was marked by almost continual warfare. 3. In terms of administering his empire, Charlemagne divided his kingdom into several hundred counties or administrative units. At the head of these units were the counts, who remained as local magnates and retained the right to their own armies. The counts had three main duties: a) to maintain local armies loyal to the king, b) to collect taxes (tributes and dues), c) to administer justice. 4. To insure that this system worked effectively, Charlemagne sent out messengers (missi domini), one from the church and one lay person, to check on local affairs and report directly to him. Charlemagne also traveled freely throughout his kingdom in order to make direct contact with his people. This was in accordance with the German tradition of maintaining loyalty. He could also supervise his always troublesome nobility and maintain the loyalty of his subjects. IV. Although the Carolingian Empire attained great territorial expansion (although not as great as its Roman predecessor), nevertheless the empire ultimately crumbled. There are three main reasons for the dissolution of Charlemagne’s empire: 1. The empire was “ungovernable.” By that I mean that there was simply too much regionalism, and counts took more and more advantage of their position of power. Also, the missi dominici (the messengers) were ultimately unsuccessful at keeping an eye on the counts and limiting their power. 2. Charlemagne was succeeded by his son, Louis the Pius (814-841), who in turn was succeeded by his sons. Rather than choosing among his heirs, Louis divided the empire among his heirs. The Treaty of Verdun (843) ultimately divided the empire into three sections. The division only served to weaken central power and make the pope stronger and more influential than the emperor had been. 3. There were renewed invasions from new “barbarian” tribes, including the Muslims, who invaded Sicily in 827 and 895. Muslim invasions disrupted trade between the Franks and Italy. Additionally, the Vikings came from Denmark, Sweden and Norway and invaded the Empire in the 8th and 9th centuries. The Danes attacked England, and northern Gaul. The Swedes attacked areas in central and eastern Europe and Norwegians attacked England, Scotland and Ireland and by the 10th century, had found their way to Greenland. The third group of invaders were the Magyars who came from modern-day Hungary. Their raids were so terrible that European peasants would burn their fields and destroy their villages rather than give them over. All these invasions came to an end by the 10th and 11th centuries for the simple reason that these tribes were converted to Christianity. And it would be the complex institution known as feudalism which would offer Europeans protection from these invasions, based as it was on security, protection and mutual obligations. From Political Fragmentation to Centralization As central authority disappeared into chaos, under the feudal system, local elites began to assert greater autonomy and authority. This led to a transformation of administrative offices into positions of inherited dynastic rule. Over the 9th and 10th centuries, duchies, counties, and many other small polities emerged as independent states. This was especially true in central Europe. Kings still existed and were recognized as such, but they were politically weak, equal in power to the great lords of their realms. The 900s saw conflict over the crowns in the eastern and western regions formally united under Charlemagne. In 987, in the west, the conflict over the crown of the western Frankish kingdom was resolved in favor of the Count of Paris. He came to the throne at a time when much royal power had been lost, and therefore he was not regarded as a threat. However, he began a program of centralization that over the centuries would result in the creation of the kingdom of France. More important at the time were the developments in central Europe. Recall that during the first half of the 900s, the land had been ravished by the Magyars. In 955, the nobles of the German lands united under the leadership of Otto, Duke of Saxony (ruled 936- V. 973). That year, Otto defeated the Magyars and pushed them back into Hungary. After his victory, Otto was proclaimed Emperor on the battlefield by the nobles. He would be formally crowned by the Pope in 962, reestablishing the Holy Roman Empire, which would last until 1806. Otto used ecclesiastical authority to consolidate his power, personally establishing bishoprics under his control throughout his lands, particularly in the east. Throughout the last years of his reign Otto engaged in a series of wars to restore Imperial power over parts of northern Italy, the Rhineland, and Bavaria. A major moment occurred in 972, when Otto returned territories in southern Italy to the control of the Byzantine emperor. In return, he received recognition of imperial power, formalizing the political division of east6 and west. This agreement was sealed be the marriage of Otto’s son to the daughter of the Byzantine emperor. Emperors, Popes, and the Crusades At the time of the reestablishment of the Holy Roman Empire, emperors dominated the popes, as seen in Otto’s ability to establish his own bishopric with minimal papal interference. Otto and his successors saw themselves as the heirs of Charlemagne, the secular defenders of Christianity, and therefore as deserving a leading voice in religious affairs. For example, Otto declared that no pope should ever be consecrated without first swearing allegiance to the emperor. However, the Holy Roman Emperors found it impossible to maintain supreme authority, as the German nobles chaffed at strong central authority. Within a century of Otto, popes moved to reassert authority over the emperors. In 1059, Pope Nicholas II declared that future popes would not be imposed by the emperors, but instead elected by a select group of bishops know as cardinals, who would be chosen by the popes. In 1075, Pope Gregory VII (1073-1085) issued a papal document (bull), known as Dicatus Papae, which advanced the doctrine of Papal Supremacy. Gregory claimed that the Church under the popes had supreme legislative and judicial authority over ALL of Christendom. This document also asserted the right to depose any and all princes. Also, Gregory announced that only the pope could appoint Church officials. As a sign of his independence, Gregory issued this bull without notifying the Holy Roman Emperor of his intentions. This led to what is known as the Investiture Conflict, at its most basic a struggle for power over Christendom between emperors and popes. The conflict was over who had the right to appoint, or invest, bishops. This was significant because bishops had great secular as well as spiritual authority and controlled great amounts of money and land. Their loyalty could be an effective tool of political power. The conflict lasted for a long time. The decentralized nature of feudalism in Germany ultimately worked against the emperors. By the end of the 1000s, the papacy had emerged victorious. This was symbolized in 1077, when the pope excommunicated the Holy Roman Emperor, thereby exiling him from the Christian community and salvation, and forced him to beg forgiveness by making a pilgrimage on foot to the pope’s mountain retreat at Canossa, the last several miles on his hands and knees. This would be the height of papal power during the Middle Ages. Imperial authority began a long decline. In 1356, the popes issued what was known as the Golden Bull, which established an elective emperorship, transferring power within the empire from the emperors to the nobles. In the late 11th century, the popes used their heightened authority to solve one of the central problems of the feudal system. This was the problem of violence. Central authority had little power to stop conflicts between individuals who had gained local power and, more importantly, offensive and defensive military capabilities (knights and castles). The popes used two main methods to accomplish this goal. They used the moral authority of the Church to limit the endemic warfare. For example, they banned certain military technology, such as the crossbow, and in the 11th century, elaborated the doctrine known as the Truce of God, which suspended all warfare from Wednesday evenings through Monday morning, as well as during all holy festivals. More importantly, and more effectively, the popes moved to export the violence. This led to the military expeditions to the eastern Mediterranean which we know as the Crusades. The Crusades mark the first time since the days of the Romans in which peoples from the west traveled and mounted military offensives in the east, signaling western Europe’s revival. The crusading era lasted from 1096 to 1272. There were 8 main crusades, each averaging 1-4 years in length. The first Crusade (1096-1099) was the only successful expedition. It was preached by Pope Urban II in 1095, and its goal was the “liberation” of Jerusalem. In return for their service, the pope granted crusaders absolution for the penance due for their sins, in this life or the next, a grant known as a papal indulgence. The popes also gave the warriors freedom to keep any booty they seized. In 1099, Jerusalem was taken and, once again, instead of returning lands originally under the authority of Constantinople, the westerners established their own rule. It is important to know that this effort only succeeded because of disorder in the Muslim world. Needless to say, the attack led to unity within Islam, under the rule of a charismatic king known as Suleiman the Magnificent. Very quickly, the Crusaders came under pressure and, by 1187, Jerusalem was retaken. The remaining crusading kingdoms would linger for under a century more. Three big points about the Crusades: 1. The expeditions to the Holy Land were not the only Crusades. Efforts were launched against non-orthodox Christians in southern France, and against pagans in eastern Europe. 2. The Crusades reflected how much the west had revived since 476. 3. The Crusades were a multi-national effort. The crusaders were all volunteers from all over Europe. The popes were dependent on others to answer the call and mount/finance the expeditions. The Crusades appealed most tto younger sons of noble families, who saw a chance to gain land and reputations. The Crusades declined for several reasons besides the growing strength of the Muslim world. First, motivations of personal greed began to overwhelm spiritual concerns, which caused doubts about the holiness of the enterprise. Second, crusades were expensive. The papacy never paid at all, and rulers became less willing to spend great amounts of money and go into debt. Also, nobles became less willing to leave their property behind for long period, and risk the loss of all they owned back home. Third, internal political rivalries weakened the effort. The Crusades did export feudal violence, VI. but never solved it. The various kingdoms established by the crusaders ended up fighting against each other as much as against the Muslims. Indeed, there were times when Christians allied themselves with Muslims against their fellow Christians. The Crusades had several important results: 1. The Crusades worsened relations between the Christina and Muslims worlds, Indeed, soon after the Crusades, the Muslims counterattacked, pushing into Europe itself, destroying the Byzantine Empire by 1453. 2. The Crusades also annihilated any possibility of reconciliation between eastern and western Christendom. The Fourth Crusade (1203-1204) saw the western crusaders sack and take over Constantinople. 3. The idealism of the Crusades encouraged the spread of chivalry. 4. The efforts reopened the eastern Mediterranean to western European trade. New products and old ideas flooded into Europe. This trade increasingly came under the control of Italians, specially the city of Venice. Thanks this trade, the Italian peninsula became immensely wealthy. 5. The Crusades led, ironically, to a decline of papal authority. Popes became increasingly dependent on secular rulers for money and troops, specially the king of France, who provided the greatest number of crusaders. This dependency on the French was strengthened by continuing papal conflict with the Holy Roman Emperors. By the beginning of the 13th century, French kings dominated the papacy, so much so that for 70 years, beginning in 1305, the popes left Rome, establishing themselves in the papal city of Avignon, located in southern France. By the 1400s papal prestige had declined so much that 3 men each claimed to be pope. This episode is known as the Second Great Schism. Plague, War, and the end of the Middle Ages The 1300s were a grim period in European history, during which the continent experienced a series of disaster which, cumulatively, destroyed the medieval system. By the 1310s, because of its over-population, Europe experienced a series of largescale famines. A much worse disaster occurred in 1347-9, when a highly virulent disease, originating in Asia and following trade routes, swept across Europe, beginning in Italy and moving northward. This disease, the Bubonic Plague, is also known as the lack Death. It was highly contagious, and most people died within a week of contraction. It received its colorful name because its most common symptom was the growth of black, pus-filled lesions, or buboes, in the armpits or groin. When the first wave of plague had past, by 1351, on average more than one third of the population of Europe had perished. This rate was worse in certain areas, particularly cities, some of which lost over 75% of their people. One of the major results of the Black Death was the destruction of serfdom. Due to the decimation of the labor force, survivors were in high demand and so could begin to negotiate to a level impossible earlier. This meant change and instability, two things anathema to the medieval society of orders. For these reasons the century immediately following the Black Death has been called the “Golden Age of the Peasantry.” At the same time, a long-term series of wars erupted in France over the issue of subinfeudation we mentioned above. Because of various dynastic marriages between ruling European families, by the 1320s the kings of England had a credible claim to the throne of France. Needless to say, the French refused to accept this and invented legal means to prevent absorption into England. In 1337, the king of England raised an army and invaded France. This began a series of wars which lasted until 1453. By 1400, the war had devolved into a series of bloody raids across the French countryside, which destroyed the French economy and weakened central authority. Indeed, the French monarchs lost most of the major battles of the wars. However, thanks in part to their always greater potential in terms of men and materials in comparison with England, as well as their timely use of gunpowder, the French were able to turn the tide and ultimately win the war. By the mid-1400s the northern part of Europe was exhausted, having been ravished by a century of war and disease. Thus the order which the feudal system had created was irrevocably broken.