ACTIVE LECTURING

advertisement

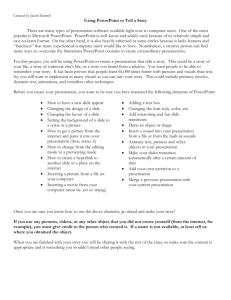

ACTIVE LECTURING The Potential of PowerPoint There are many reasons why PowerPoint is becoming more widely used in college classrooms. Students frequently ask professors to prepare their lecture notes using PowerPoint, and as more and more classrooms become wired, it’s easy to use presentation technologies in them. There are both positive and negative aspects to using PowerPoint in the classroom. First, the positives. PowerPoint is easy for professors to update, saving them time and energy. It’s neat and clean, and it allows for "portability" of materials. Professors can take slides from one lecture, update them, include them in another lecture, and share them with colleagues or students. It also provides a platform for incorporating a variety of different kinds of multi-media file-types: images, video, audio, and animations. There are also drawbacks to using PowerPoint as a teaching tool. PowerPoint, when used incorrectly, can encourage student (and teacher) passivity by discouraging interaction between them. Professors often overload slides with information, forcing them to move through the material too quickly while overwhelming students with details. This can sometimes discourage students and lead them to stop listening to the lecture altogether. So, we're left with the obvious: PowerPoint is only a tool. It will not, in and of itself, improve student learning. It’s the way that professors use PowerPoint that can encourage student learning. By strategically employing it to create opportunities for active learning, lecturers can capitalize on PowerPoint's strength as a presentation platform to engage students in the learning process. To that end, we’re going to be talking about a variety of active learning strategies that you can use to help students learn more from your lectures. Preparing to use PowerPoint in the Classroom You can use PowerPoint to improve students' learning before you even get into the classroom. First, you should think carefully about what part of your lecture you want to make available for students either before or after class. Many faculty choose to do this and others choose not to for a variety of reasons. Some faculty are afraid that handing students copies of their presentations will discourage them from coming to class. And in some cases this might happen, particularly when the expectation is that the lecture itself provides no added benefit—ie, is simply a rehashing of what's on the PowerPoint slides. Students' learning can be improved, however, by avoiding handouts that simply duplicate your in-class presentation and providing instead a skeletal outline of the lecture content or a list of questions to be discussed in class. In the latter case, students will be compelled to come to the lecture because you and they will be filling in the information together during class. If the handout is made available prior to class, students will be able to preview the content of the session's lecture ahead of time so that they can come prepared for the way ideas relate both to one another and to things that they already know. You can also encourage student learning in handouts by leaving blank slides, slides that ask questions, or slides that ask students to fill in information at various points. For example, at certain points in a handout you may have students come up with a question of their own or respond to one that you provide. In this way, students are encouraged to engage the material at a high level as they prepare for your class or review afterwards. You’ll likely have better attendance and notice that students come to class prepared to absorb and to discuss the information that you’re presenting. In addition to providing (and provoking) questions, which can enliven your lectures, PowerPoint can actually improve note-taking abilities. This might seem counter-intuitive at first, because if you hand students a print out of your slideshow the material is already copied for them. It's important to remember, though, that in this case students will have accurate information. Students won’t miscopy equation sets or misspell foreign names. You can also guide and focus students' note taking on what you consider to be higher order skills. Rather than becoming stenographers, feeling compelled to write down every word, students can be asked to note and work with information in an active way. They can synthesize material and spend less time reciting, in written form, the content of the lecture. For further information on creating and using PowerPoint handouts effectively, see the section on effective handouts. The Beginning of a Lecture Lectures have beginnings, middles, and ends. Each of these parts has different goals that you should try to meet. Let’s start with the goals for the beginning of a lecture. First of all, you should try to gain students’ attention and motivate them to learn. PowerPoint can be used very effectively to this end. You can put up an image that relates to the day’s concepts, you can play music, or have a short video clip to draw their attention or stimulate discussion. At this stage the point is simply to bring students into the sphere of your topic. Secondly, an important goal of the beginning of a lecture is to tell students what they will learn in the day’s session. You state your objectives. Presentation technology allows you to easily enumerate your main points and what you expect students to gain from the session. Students learn by connecting what they know to new concepts, so this is extremely important. There are a variety of different strategies for getting students to stimulate their prior knowledge of a topic before you progress to new material. You can start with an opening question. Prepare a PowerPoint slide that simply says “Opening Question,” and then present your question. You can do a variety of things with this. You can have students write about the question or think quietly. You can do a "think-pair-share" activity in which students think for a few moments about the question, pair up with a partner to discuss the question briefly, and then come back to share their thoughts with the larger group. This also helps you assess students’ knowledge of the particular topic and might help you then shift the focus of your lecture to what students actually need. There are many different activities you can use in this manner. An example is brainstorming. Again, have students select a partner, show a slide that presents a question or statement, and ask students to think of as many things as they can that relate to this particular topic. They should write down their results, either as lists, concept maps, or in a narrative format. In this way, you’re getting students to think about the material and you’re getting them ready for what comes in the middle part of the lecture. The "Meat" of the Lecture The mid-point of the lecture is where you present your content. This is also the point in which most faculty go roaring forward. One of your strategies for the middle point of the lecture should be to pause every twelve or fifteen minutes for students to process the information actively. Research has shown that people can’t attend to lectures for longer than about twelve or fifteen minutes. If you lecture for longer than this students begin to lose focus and their minds will wander. It's in these lulls that you want to shake students from their oncoming stupor! This is when trying some kind of active learning technique would give you your greatest chance of success. Many instructors are relucatant to try active learning strategies during a lecture for a variety of reasons. Some don't think active learning strategies can work in large classes, but this in fact is not the case. Active learning strategies don’t need to be difficult to manage or take a lot of time. They can be one or two-minute activities, done alone or in pairs, that break up a lecture at twelve or fifteen minute intervals. Some of the strategies that we are going to talk about can be adapted very nicely to this particular timeline. One of the advantages of PowerPoint is that you can build active learning strategies into your slideshow that remind you to stop and take a breath at various points during the lecture. If you don’t have these activities built into your lecture, it’s very easy to just keep moving forward. Let’s talk about some of the strategies that you can use in the mid-point of a lecture. First, as we have already noted, you can use a think-share-pair strategy based on questions that you develop or that students themselves develop. An interesting strategy that you can use during the mid-point of a lecture is the “stump your partner” strategy. Ask students to turn to a neighbor and come up with a question that they feel is difficult. They should try to stump their partner. You can then collect some of these questions either verbally or on 3 x 5 inch note cards and re-purpose them in other lectures, in practice exams, or on a mid-term. This gives students a greater investment in the course content and what they produce. And it’s also fun. You can also do a "note check" during the mid-point of a lecture. Again, introduce the activity on a PowerPoint slide. Ask students to turn to a partner and compare notes, focusing specifically on what the most important points of the preceding content are and what they are most confused about. You can collect this information verbally or on note cards and use it in a variety of ways. For further examples of active learning techniques you can use with PowerPoint see the section on active learning. Wrapping it Up The end of a lecture should be like the end of a good story. It should summarize the information, provide closure, and ask students to connect the information to themselves, their own values, and its application to the world. You can achieve this in a variety of ways. First of all you can ask students what the muddiest point of the day was. Type out "muddiest point?" on a slide and ask students to write about this. You can then collect the information either verbally or on 3 x 5 inch note cards. You might also have a slide that asks students for any "final questions." In this way, you encourage students to process the material and communicate with you about it. Finally you can ask students to answer two or three very brief questions. We call this a classroom assessment technique. In a sense what you are doing is asking students if they understood what you consider to be the most important parts of the day's material. You can collect this either verbally or in writing, and it will help you assess whether or not you’ve met your teaching goals. If not, you can cover some of the material at the start of the next day's lecture or create assignments that will help students process it. In addition to assessing your students, you're really demonstrating to them that you genuinely care about their learning and that they are achieving what they set out to by enrolling in your course. For further information about using PowerPoint for classroom assessment, see the section of this tutorial titled formative assessment. © Bill Rozaitis and Paul Baepler, 2005