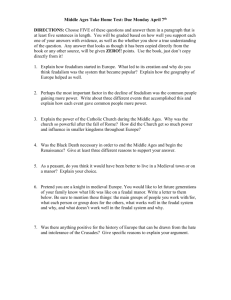

12. European Feudal Society

advertisement

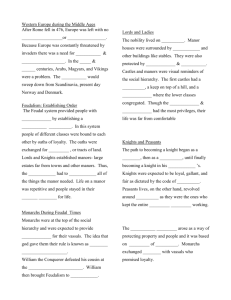

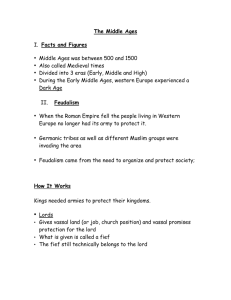

European Feudal Society In the instability created by the collapse of both the Roman Empire and of Charlemagne’s Empire, the one stabilizing force in Europe was feudalism. Feudalism provided the crucial bridge from near-anarchy to the formation of modern nation-states, and its impact on all aspects of society was felt long into the modern era. This lesson will deal with the time period from roughly 900 to 1200 when feudalism was prevalent across Europe. Feudalism is notoriously hard to define, so watch the italics carefully. With collapsed governments and Christendom on the brink of annihilation by outside forces, feudalism was a local effort to avoid anarchy. These outside forces included Vikings and Magyars as we have seen, but also Muslims. All of these were considered pagans by Christian Europe and therefore all the more frightening. Europe was surrounded by hostile invaders. Some areas were merely depopulated. Many areas were completely impoverished. Monasteries, religious institutions that were the last holdouts of scholarship and learning, were plundered and destroyed. But then Europeans stopped the invasions. Only Normandy and Hungary were permanently lost, and the Norsemen of Normandy and the Magyars of Hungary were converted to Christianity. The Muslims were pushed back from their original line of advance and eventually pushed off the continent. Feudalism helped Europe accomplish all this and set the stage for much more. Europeans were successful in stopping these invasions for many reasons. These new invaders were not as numerous as the Huns and Germans that took out Roman authority. The Church was also increasingly militant as evidenced by the Crusades of which you will learn more, later. Another key reason is our second definition because feudalism was the emergence of local defenses. Local leaders rose to the task first in France, where they were called Counts, and as they led the resistance they gave rise to a third definition—feudalism was a new system of government. The Counts who led the resistance ruled France unless they chose to unite behind some person who claimed to be a king. The professional fighting men, the knights, were controlled by the various Counts, and these interlocking connections were the government. Invasions pummeled Europe into local self-reliance. This isolation stifled the economy of Europe; therefore, feudalism was a result of the breakdown of economic ties, or the death of trade. Feudalism’s answer was to create completely self-sufficient communal farming villages or manors on land owned by feudal leaders like Counts. A Count, or “Lord of the Manor,” organized the labor of the peasants in his district and charged them various fees for services they could not otherwise secure. Some peasants fell into debt as a result of Europe’s crippled economy and were tied to the land as serfs. In return for a place to live, both free peasants and serfs served as infantrymen in medieval battles fought by the Counts. Feudalism and the manor system provided enough stability to check the population decline and actually allowed an increase in population just in time for Europe to weather the effects of wars, Crusades, and the Black Death. This societal revival depended on an increase of agricultural productivity that was achieved by the manor system. Better tools, better organization of labor, and better farming techniques resulted from the efforts of lords of manors to organize the peasants into tightly integrated communal farming villages. After feudalism had taken root in the 9th and 10th centuries, the manor system followed and actually outlasted the feudal system, continuing to the 15th century. Arable land on a manor, the land that could be cultivated, was divided into large fields worked by all the peasants on the manor, and a system of crop rotation was invented to increase the yield by letting certain lands periodically lie fallow to preserve the fertility of the soil. The manor system thus created self-sufficient estates held either by a Count or later by prominent Church leaders as part of their salaries. Each lord maintained a Church for his village and thus employed a priest. While feudalism was the political and military system, the manor system organized the rest of society, especially the economy. Each lord of a manor administered his land and organized “public” works on his private estate like the construction and maintenance of roads. Since the manor system outlasted feudalism in Europe, once nations returned these hereditary land holdings were the origins of European aristocracies. Despite the fact that the property of Europe fell largely into the hands of relatively few families, the people of Europe were saved from starvation and violent death for centuries. This simple lifestyle only ended with the emergence of towns, moneyed economies, monarchies, and nations again. You can sense a fifth definition coming, and you are right—feudalism was a way of life. Coupled with the manor system feudalism was an economy and a government and a society all wrapped into one. Europe thus discovered the bare minimum requirements of civilized government. At bottom, a civilization must provide two commodities for its people that they cannot provide for themselves—justice and protection. The dark side of this principle is the fact that in times of chaos, whoever provides justice and protection will be the government. In chaos, people will even submit to tyranny (or become serfs) in order to secure peace (justice and protection). Why did feudalism spread to all of Europe? Feudalism provided justice and protection tailor-made for its times. Justice, by the way, is the settling of internal disputes within a realm by a disinterested umpire. Protection is the settling of external disputes with a “big stick,” or a military. Feudalism perfectly supplied justice and protection when civilization teetered on the brink of anarchy. Feudalism was the break-up of political authority. For over three centuries there were no empires, nor even countries, in Europe. Therefore feudalism was public power in private hands. Justice and protection were provided by individuals, and all of this system therefore depended on the fact that feudalism was defined by the LordVassal relationship. What is a Lord-Vassal relationship? Let us demonstrate: Pause for a ceremony. Wasn’t that nice? The fief alluded to in the ceremony was a reference to a portion of land entrusted to the vassal by the Count who owned, by virtue of governing it, a giant estate called a—guess what—county. The Count had a castle from which to administer justice and protection, and his office was a private, hereditary possession to be exploited for his own benefit. The right to govern became associated with the ownership of the land, and both were hereditary. The Counts could give away either the right to the land or the right to govern or both to his many vassals who would control their various portions of land (fiefs) for the Count and only indirectly for themselves. Some vassals lived with the Lord (or Count) and ran his personal estate and were therefore called viscounts. Others merely gave homage to a Lord to receive his protection when they owned land but couldn’t protect it themselves. Many vassals had their own vassals beneath them, and to their vassals they were known as Lord even if they themselves had a Lord (or sometimes two). Confused yet? Let’s go back. The basic relationship gave vassals land, or a fief. Fief is the Old High German word for cattle or property. The Medieval Latin word for property was feudum, hence our words feudalism or feudal. In return, vassals (the Celtic word for servant) had to give aid to their Lord in war (providing protection) and help him oversee the life of his subjects (administering justice). This arrangement is feudalism in its most basic form. Things really got complicated when some vassals late in the medieval period pledged loyalty to more than one Count in order to get more land, and then those Counts went to war against each other. . . Therefore, two more definitions are in order—feudalism was a system of interlocking personal relationships, and feudalism was an individual desire for wealth and power that exploited a collective need for security. Remember, feudalism arrived in France first then spread to the rest of Europe. Russia adopted it, and Japan spontaneously resorted to the same system in similar circumstances. The Magyars admired it and converted to Christianity in order to get it. If you forced me to express a definition of this complex system in one sentence, it might read like this: In the face of invasions and the collapse of government and trade, feudalism was the emergence of local defenses that gave rise to a new political situation and to a new way of life based on the Lord-Vassal relationship where public power existed in the private hands of ambitious warriors. Still not clear? If you imagine a social structure shaped like a pyramid you will understand feudalism. At the top of the pyramid sat a Count. He had several vassals beneath him to which he gave land, and each of them had several vassals beneath them to which they gave land and so on until all the Count’s land was subdivided into tracts roughly 1,200-1,800 acres which made up the private estates of the lowest level of vassals. Each tract of land this size was called a manor. For perspective, a manor was two or three times the size of the largest farm in Anderson County (which belongs to my Uncle to whom I was indentured as a serf for around ten years of my life). If you lined up all the Counts of France, or any other region of medieval Europe, you would see a whole slew of pyramids beneath them that constituted the social, political, military, and economic organization of medieval society. Remember that the base of each pyramid rested upon the backs of serfs. As to government, vassals had to administer courts as well as witness the acts of their Lords in higher courts. The pyramid of vassals ran smaller and smaller districts down to their management of the lives of the serfs and peasants on their own manors and those of the members of their own households. Military power was based on personal relationships that controlled the new military tactics in place by the 8th century. Military engagements required large numbers of heavily armed and armored cavalrymen, the most powerful warriors on the continent who were called, of course, knights. Each Lord, all the way down to the last tier of vassals, surrounded himself with knights loyal to him alone. This loyalty was created by the fact that landless freemen could not afford to outfit themselves with the specially-bred heavy horses, the armor, or the swords. Only the wealthy Lords could afford to provide the horses, with innovations like the stirrup, and swords, which cost the equivalent of $20,000 to $30,000 in today’s money. The knights, thus equipped, became the most effective element in land warfare, and they were loyal to their master and to him alone. Their master’s oath of loyalty might draw them into his Lord’s wars all the way up to mustering an entire region’s military might based on our definition of feudalism—personal relationships with marriage-like vows binding men to military service. Europe therefore received protection. Justice was provided by traveling courts administered by a Lord and requiring the attendance of all his subjects from vassals to knights and other freemen to the serfs from the various fiefs. All of feudal society was therefore governed by the personal relationships which gave the French (or other) Lords political and military power. If an individual claimed to be a King of France, the Great Counts bargained with him for new offices and lands when he asked them to assemble their forces for battle. The Great Counts recognized a king’s nominal superiority especially to prove their ownership of new lands, but by the 10th century they were just as likely to turn on the king and depose him. France was really ruled by the Great Counts. To be a Great Count you had to have land (lots of it), vassals (lots of them with vassals of their own), and castles. The vassals submitted to this arrangement saying, “No Lord, no land,” but most vassals secretly hoped to get castles. Despite the kiss and the pledge most vassals hoped to become independent like their Counts, and remember the final definition of feudalism— the individual desire for wealth and power harnessed aspiring men to meet the need for collective security. Feudalism worked in France and spread to all of Europe.