Rippenschaber der jungpaläolithischen Fundstelle Meiendorf

advertisement

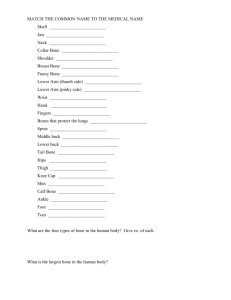

„Prehistoric Europe, where are your osseous Wet-Scrape Tanning Tools?“ Archaeology and Functional Analysis of Bone Edge Tools © Markus Klek, 2009 “Auf der Suche nach dem Naß-Schaber” Archäologie und Funktionale Analyse von Knochenwerkzeug mit längsstehender Arbeitskante Introduction: Regarding my yearlong interest in prehistoric tanning technologies, I am researching European prehistoric worked bone assemblages for artifacts associated with the working of animal skins. Generally, the subject of hide working has been largely neglected in experimental archeology and the literature is full of incomplete, misleading and unspecific assumptions regarding the subject, mostly due to inadequate knowledge of the technical processes involved and the lack of sufficient practical experience. There are some noteworthy exceptions to the rule like the works of Anne Scheer (Scheer 1995...), Patricia Legrand (legrand....) and.... With this paper, my special focus is on tools with a sharp and distinct working edge along the long axis of the bone. Assumedly such artifacts were held horizontally with both hands in order to clean skins pinned to a wooden beam. My own research of ethnographic data from North American, as well as extensive experimentation with historic Native American replicas show that such artifacts present an ideal type of tool for wet- scraping the hides of deer and other small to medium sized ungulates in order to produce leather. In fact edge tools (also called ‘beamer’ or simply ‘scraper’ in this article) represent the predominant type of tool for such work in North America (outside the arctic) as pointed out in the research of Matt Richards (Richards 2004, 2). These artifacts could be fashioned from complete bones of large ungulates such as ribs, metatarsi, ulna and radius or from bone shards set in a wooden handle.(Literature...) Apart from the predominant application in North America, beaming tools made of bone or metal were in use through the millennia, as among historic Eurasian subarctic tribes (Klokkernes 2007, 51; Bogoras 1909, 216-219), the ancient Scythes (Sembach 1984, 259) or the Romans (Rahme 1995, 2) for example. The two handed beamer has even survived until today in the form of the “shaving knife” still widely used in modern tanneries. Therefore it is remarkable that such edge tools are very rare in the archaeological record of Central Europe. From the late Paleolithic to the Neolithic, edge tools seem to pose a rare find. This article tries to create awareness for this type of artifact by presenting a number of such assumed hide working tools in the context of their functional analysis based on experiments with reproductions and my long term practical experience with such edge tools. Tanning Terminology: In the context of this article we are mostly concerned with the production of leather, that is tanned animal skin with the hair removed as opposed to fur in which case the hair is retained. Before tanning is accomplished an animal skin needs to be cleaned of hair, epidermis and some cases the papillary layer on one side as well as of fat, flesh and subcutaneous layer on the other side. Such work can be carried out when the skin has been dried prior to scraping, so called dryscraping; or when the skin is in a soaked or wet state, so called wet-scraping. Dry- scraping is generally accomplished with sharp tools, in a prehistoric context most likely out of stone such as flint. Wet-scraping on the other hand is associated with bone edge tools. Dry-scraping is mostly practiced on large hides or when the hair is to be retained, while wetscraping works best for the production of leather using the skins of small to medium sized ungulates. Variations of course do occur and a combination of both techniques is also possible. In the case of wet-scraping the skin to be cleaned is draped over a beam of wood and the material to be removed is scraped away with the beamer held horizontally in both hands. Bone offers the ideal prerequisites for such an undertaking. It can not be made too sharp to accidentally cut the skin, while still being able to hold a distinct edge necessary for removing unwanted tissue. It is readily available, does not take a lot of work to shape into an effective tool and is easy to resharpen. In fact certain ribs of some animals can be used directly A number of beaming tools manufactured and used by the author: Left, Image 1: top, close up of the working edge of a replicated Plains Indian bison rib scraper, extensively used. Left bottom two, Meiendorf beamers broken during use. No1 and No2. Right, Image 2: top two, bison rib scrapers, bottom one same as image 1. Right center, red deer rib, ready for use without modification Right bottom two, Meiendorf scraper broken during use without any initial modification at all, as the nature of the bone offers enough of an edge for scraping skins (see image 2, center). In the archeological context such “spontanious” or “ad hoc” artifacts (Schlenker 2008, 34; Choyke 2007, 58; Steppan...; Stratouli?) would initially make for minimal signs of manufacture or use-wear on the bone which might not be readily recognizable to the untrained eye (Literature...). Even more so when dealing with badly preserved or strongly fragmented finds, which are then hard to classify and rarely make their way into any publications. Example no. 1: Elephant bone beamers of homo erectus? The exceptional site of Bilzingsleben (Germany) offers a large assemblage of osseous remains from the Middle Paleolithic. At this location, more than 300 000 years ago, homo erectus has produced a number of bone tools of which one type can be regarded as beaming tools. 12% of all retrieved bone implements belong to this type. They were all produced from the upper arm or thigh bone of elephant. These bones were split longitudinally, the spongiosa was removed and one of the resulting long edges was carefully retouched with a hammer stone, producing a sharpened and straight working edge. Scratch marks indicate that the tool was held with both hands and used at a right angle to the edge. Most working edges show strong use polish. The tools measure from 25 to 80 cm in length (Mania 1990, 159). All of the above features could to point towards a wet-scrape beaming tool. Mania also speculates on its use in preparing hides. Except that the size of these implements appears to make them rather unwieldy and bulky tools. It is hard to imagine how one can be able to handle a 60 or 80cm long and maybe 12-15 cm wide tool, scraping hides on a beam, not to mention the weight that such a bone would have (compare measurements in chart below). Due to the transmission of force, beaming tools work best when the handle is close to the beam. Especially with bone scrapers, sometimes a lot of force needs to be applied and a bulky, large and heavy tool is not an advantage. Especially when one keeps in mind that homo erectus was on average probably one head shorter than modern man (average 165cm, Hoffmann 1999, 116). Maybe longer pieces were raw products to be cut short in order to make more serviceable tools. Experiments: Due to the lack of elephant bones or bones of comparable size and morphology, I was not able to replicate and test these artifacts. Example no. 2: Rib Edge Scrapers from the Late Paleolithic site of Meiendorf ?: The site of Meiendorf (Germany) has been excavated by Alfred Rust in the 1930‘s. The people of the so called „Hamburger Kultur“ were predominantly reindeer hunters and flourished around 13 000 –10 000 BC. Among the organic artifacts only the ribs of large mammals, in this case reindeer and horse, seem to have been modified into tools. Rust identified 8 such artifacts, which he called „rib knifes“ ( Rippenmesser) or “fur knifes” (Fellmesser), without specifying what led him to such identification. He differentiates between two types of rib tools. The second type (type 2) of which one unfinished and six broken pieces are available for study, is the one we are dealing with in this article. Due to the fact that no complete tool remains, it is uncertain if these artifacts actually had the morphology typical for beaming tools. But the fact that fragments with proximal as well as distal ends are among the finds suggests that this might be the case. Furthermore, the jagged edges seem to indicate that the tool was initially much longer and broke during use. Rust describes them as follows: “Considerable parts of the compacta and underlying spongiosa were removed, usually from the outer side of the rib bow. One half to two thirds were thus removed and the resulting, prominent edge was sharpened with silex knifes. The two ends of the ribs were left unworked for the last five to ten centimeters...it appears that these tools were used extensively. Regarding the possible way of manufacture he writes: “...all pieces are showing a jagged and irregular separation line. Especially the unfinished piece nicely demonstrates this process of production....clearly small holes produced by a pointed stone (?) are distinguishable. Thus the whole extend of the compacta to be removed was destroyed...” (Rust 1937, 106-107 and Fig. 47). The inventories excavated by Rust have survived the ravages of the war and are today housed in the Archäologische Landesmuseum Schleswig Hosteins at Schloß Gottorf. In order to find out about possible modern research on the bone artifacts, I have contacted the director of the Archaeological Central Archives (Archäologisches Zentralmagazin) Mrs. Dr. Ulbricht as well as the archaeozoologist Dr. Ulrich Schmölcke, but no such data seems to be available. Thus it remains unclear if Rusts observations regarding manufacture and use hold up to modern scientific scrutiny or if more ribs with less obvious signs of use are among the inventories. Likewise, measurements of the originals are not available. Further research on these artifacts would be of great use. Thanks to Mr. Schmölcke I received information about one other rib scraper (Excample No. 3). But it is uncertain if there are more such artifacts among inventories from other Hamburger Culture sites in Northern Germany, England or the Netherlands. Thomas Terberger who examined the assemblages from late glacial Endingen (Example No.3) stated, that he was not familiar with anymore such tools from Northern Germany (Lit....). Left, Image 3: (Fig 46 after Rust 1937): on the left, complete Type 1 tool from Meiendorf and three fragments of Type 2. Right, Image 4: (fig 47 after Rust 1937): three more fragments of Type 2. Experiments: I have experimented extensively with different ribs as beaming tools. The mode of production suggested by Rust has been applied to three ribs of red deer and one of bison. Three horse ribs, as well as two ribs of adult moose and 5 of domestic cattle were also taken into consideration, but all had to be abandoned from the onset due to their extremely thin compacta which would prove unable to stand the pressure exerted during scraping (This only shows, that the individual ribs available were not usable , not that ribs of the mentioned species in general are not suitable for producing beaming tools). Reindeer ribs of the required size were not available, thus red deer was chosen because of the comparable body size of the two species (No1. Measured 29,2 cm long, and 20mm wide in the center of tool and 8 mm thick in the center of tool, proximal epiphysis missing. No2. 30,5 cm long, 20 mm wide, 9mm thick; No. 3. 30,5 cm long, 20 mm wide, 10 mm thick) A piece of flint approximately the size of a tennis ball, was modified by direct percussion to form a sharp point, by which the compacta of the deer ribs were shattered. For that purpose the ribs were placed on a log to serve as an anvil. As the compacta is rather thin this did not require much force. On the contrary, special attention had to be paid to the lower edge which was supposed to form the working edge in order not to fragment it. After this was accomplished, the working edge was prepared with a flint blade in order to smooth it out and give it a clean and sharp edge. In order to produce a usable tool approximately 30 Minutes were required. On two ribs the compacta was removed from the outside of the rib bow, on the third from the inside. During work, the tool was held in such a way, that the angle between the working edge and the hide is about 90 degrees. Due to the natural curve of the bone, the outer rib bow faces upward and the inner bow downward, to guarantee for comfortable handling (see image 6). In scraping hides of deer (capreolus capreolus) these tools prove to be very effective and need to be resharpened only 2-4 times per skin. Over time the resharpening of the edge also wore away and smoothed out what Rust called :”the jagged and irregular separation line”. But this might only be due to my specific way of sharpening the tool and was maybe practiced differently by the Meiendorf people. Furthermore, repeated sharpening will lead to an increasingly curved or concave edge. This wear pattern will intensify over time and is a trademark of all beamers used over an extended period (compare bison rib, image 2 and Example 5). The Meiendorf replicas are rather fragile tools due to the thin compacta of the ribs and the fact that a large amount of compacta was removed from the onset. Tool No1 and 2 eventually broke. The first when trying to put a leather cushioning on the handles. While holding the tool on one end and pulling tight the leather thong which was wrapped around the other end, the tool was under increased tension and broke in half. No2 broke after some use while scraping a skin. Looking at the images in Rusts publication (fig 46 and 47), the original artifacts feature similar fractures. The removal of the compacta clearly produces a weak spot for this type of beamer. Thus the idea arose to produce a tool from a stronger or thicker rib, or one with a thicker compacta. Therefore a bison rib was used. The above mentioned hammer stone proved too light, thus a larger one, which could be wielded with more force in order to pierce the compacta was applied. Nevertheless it proved impossible to aim the blows of the hammer stone in such a way as to shatter the compacta on one side of the rib but not on the underlying side which was to form the working edge. Consequently the nature of the bison rib proved rather unpractical for the production of a Meiendorf scraper in the way Rust suggested. Left, Image 5: experimental manufacture of a Meiendorf beamer as suggested by Rust Right, Image 6: Working with a rib beamer to remove hair off a deer hide Conclusions from the experiments: Experiments show that rib scrapers can be very effective, but the size and stability of the individual bone is crucial for the life span of the tool. Species, sex, age and location within the sternum are factors influencing the morphology of ribs and thus their qualification for the production of beamers. The cranial or caudal ribs of the sternum are generally too short, too thin or of an unfavorable cross section for two handed beamers. Therefore, the ribs in the center of the sternum appear to be the choice selection. The question to remain open is why parts of the compacta were initially destroyed to form the tool. These ribs would have made very practical tools without such modification and thus remain more durable (compare Example 3). My long term use of such simple beamers show that the continued resharpening of the working edge initially wears out the compacta opposite the working edge, exposing the spongiosa and ultimately the tool acquires a similar morphology as the Meiendorf scrapers (see bison rib on image 1 and 2). Could it be that Rust’s observations regarding manufacture were wrong? Example No.3: A Rib beamer from the “Giant deer-site” of Endingen ? The late paleolithic site of Endingen (North East Germany) which might be associated with the Hamburger Kultur (Terberger 1996, 28) provides us with one complete worked horse rib. This specimen is the 34 cm long right rib from the middle of the sternum, probably the sixth rib (Street 1996, 33; Terberger 1996, 20). The implement is worked along 17 cm on both sides of the inner bow to form a sharp edge. The morphology of the artifact, its length as well as the angle, position and length of the working edge identify it as an ideal wet-scraping tool. The working edge runs along the center of the inner bow of the rib and leaves 7-8 cm on the distal and proximal ends as handles. Likewise the level of usewear on the edge, namely that the spongiosa is not yet exposed, would identify this implement as a rather ‘young’ artefact which might have been used to clean maybe 2-4 skins before it was discarded or lost. Terberger and Street postulate its “exact equivalents” to Rusts Type 1 “Rippenmesser” from Meiendorf and theorize on its possible use to clean animal skins. Nevertheless a closer examination reveals that the Meiendorf artifact is only approximately 22 cm long (Rust 1937, plate 46) and thus rather too short for a scraper to be held on both ends like a beamer (compare chart below). Furthermore there is one similar fragment among the osseous remains from the Hamburgian layers of the Stellmore site, which is only 16 cm long (Rust 1994, 131 and plate 29). Therefore Rusts “Rippenmesser” of Type 1 might rather be a one handed tool used in a knife or sickle type of way and thus be a tool completely different from the Endinger rib. Experiments: As of now I was not able to obtain a suitable horse rib to replicate the Endinger bone tool. Example No.4: Neolithic bone beamers from Hungary Text complete with images at http://www.palaeotechnik.de/knochenwerkzeug.html In cooperation with Alice Choyke of the Central European University, Budapest. Typological and Archeological Facts: From the late Neolithic to the Chalcolithic, so they were in use at least for 1000 years. Appear in considerable numbers in late Neolithic sites of the Great Hungarian Plain. They are almost exclusively made from metatarsal of cattle or red deer, the species depends mostly on availability. Tools are characterized by continuously renewed and sharp edged facets along the whole length of the diaphysis, sometimes on one, two, three or all four sides. For the sharpening flint tools were used. Eventually the compacta gets too thin in the center and the tool breaks. Facets are created on the dorsal/plantar surfaces first and then, more rarely on the medial, lateral sides. Choyke suspects the curved facet is first established from one end of the diaphysis to the other (never extending onto the epiphysis) and then renewed as the two parallel edges get dulled. The tool seems to have been pulled with a hand on either epiphysis. It is very rare to find these tools complete, thus different stages of production/use can not be studied. They are used up very intensively. From analogy with similar objects from ethnographic and historical contexts these tools might have been used to clean hides pinned to tree trunks and are thus termed “beamers”. Experimental Manufacture and Use of Beaming Tools: Tool 1: Raw material: Metatarsus of red deer. 27cm long, diameter at center of diaphysis 2,0 by 2,1 cm. Intention: Recreating a tool with prehistoric methods from the initial shaping to its first stage of usability. Observing use wear through prolonged use and continued resharpening. Manufacture: Creating facet on dorsal and plantar sides, with a flint/silex with steep angled working edge, 45-90 degree; (resharpening flint by retouching working edge is not very proficient. Better take a new flake after edge is dulled). Alternatively, the rough work to create the initial facets can be achieved by grinding against a course rock or sandstone. (Some deep cuts are visible on certain beamers, maybe from initial grinding on rough surface?) and then doing the fine tuning with a flint. This way proved to be the faster approach. A facet can be created in about 15 minutes. These first working edges have very steep angles slightly larger than 90 degree, due to natural shape of bone. They are straight on one side and slightly curved on the other. Thus they only show promising keenness towards proximal end of tool, where the profile of the diaphysis is more square. Use: The tool was tried on deer skins. The hides had been salted and were rehydrated before scraping by soaking in a creek for 24 hours. For scraping a rather narrow upright wooden beam of 6 cm diameter was used. The tool proved to be able to remove hair, grain layer and also fat, flesh and membrane on both sides of the hide, but was rather ineffective due to the shape of the working edges, especially towards the distal end where the epiphysis is more rounded. Therefore two more facets were created, on the other sides of the bone, thus the tool received four working edges. The profile of the diaphysis now being rectangular. The resulting edges could be used more successfully. This shows, that in order to create an effective tool for wet scraping of hides at least two neighboring facets need to be created, sharing one clean cut working edge. During use the tool is held in such a way that only the edge is in contact with the skin, not the whole facet. It proved most convenient to use one working edge until it had dulled and then move on to the next, until all four had been used rotationally and become dulled from scraping. Sharpening of one edge can be achieved by scraping of one or both facets and requires approximately 10-20 seconds. Due to the natural shape of the epiphysis, certain positions during work are more uncomfortable for the hands than others, as the tool needs to be gripped tight and force be excerted in order to remove unwanted tissue from the skin. After prolonged work of about an hour, the palms of the hands start to get sore and red. This is typical for the use of most bone scrapers, where the handles are formed by unmodified parts of the bone. My experience with such tools is that they gain enormously from creating comfortable handles by wrapping with leather or other cushioning material. It would thus be interesting to examine the original artifacts in that regard to see if evidence of such treatment of the epiphysis is detectable. Long term use of this tool will show how the working edges will develop through repeated resharpening. An account of the hides scraped will give an indication of how long such a tool was in use before it broke. Tool 2: Raw material: Metatarsus of contemporary domestic cattle. 23,5 cm long, diameter at center of diaphysis3,6 by 3,4 cm. Realizing that modern middle European cattle are not comparable to Neolithic animals. Intention: Recreating a tool toward the end of its life, where the facets and working edges are curved and the compacta is worn through in the center. The beamer was shaped using modern steel tools because removal of large amounts of bone were necessary. This sill proved to be a lot of work. Final touches and resharpening were done with flint. Use: This tool also worked well on a narrow 6 cm diameter beam (Bone tools in general require narrower beams than metal scrapers. This becomes even more relevant when the working edges become more curved due to prolonged use of the tool). Conclusions from Experiments: So called “beamers” can make effective, long lasting wet scraping tool for cleaning skins up to red deer size. Nevertheless, judging from the provided photos, some of the original artifacts do not seem to meet the necessary requirements to make a tool effective for scraping medium to large size animals. Maybe they were used especially for small fur bearers on very narrow beams or they were used for something else, like peeling bark of small diameter wood. Thus it appears necessary to look at all the artifacts currently classified as “beamers” more closely as they might actually fall into different categories intended for different uses. Experiments do not clarify why metatarsus were used almost exclusively and not metacarpus. Both narrow and long bones (red deer) as well as shorter and stouter tools (cattle) make usable scrapers. Choice of bone material thus most likely follows the general terms of availability. Furthermore, judging from my experience with comparable edge tools, these beamers are less effective than bone scrapers which feature working edges of much less than 90 degrees, such as rib scrapers because overall resharpening time is longer and edge needs to be kept sharper than on lower degree tools to be effective. The chart below will give an overview over the artifacts mentioned in the text. A few more bone tools used extensively by the author are added (e,h,i) to give a more complete idea of the range of measurements for beaming tools. Likewise measurements of modern two handed metal beamers by three different authors are given (j-l) as comparison. Measurements for the total length of the tool can be given accurately, whereas data for the modified or sharp edge is approximate due to the fact that the transition is often gradual. Generally during work only approximately 1-3 cm of the working edge are actually in touch with the skin. This is depending on the diameter of the beam and the curve of the working edge. Artefact Total length: direct distance from epiphysis to epiphysis In cm Length of modified/sharp edge a. Meiendorf Tool1(red deer rib) b. Meiendorf Tool2 (red deer rib) c. Endingen, horse rib 29,2 12 30,5 12.5 34 17 d. Meiendorf Tool3 (red deer rib) e. Bison rib, image 1 and 2, Native American f. Hungarian beamer Tool1 Metatarsus g. Hungarian beamer Tool2 metatarsus h. Ulna radiaus red deer, Native American i. Metatarsus red deer, Native American j. Modern steell scraper Edholm k. Modern steel scraper, Klek l. Modern steel scraper, Richards 30,5 12.5 30,8 17 27 15.5 23,5 17 25,2 12,5 25 14 35-65 14-35 34-40 14-23 30-47 No data In cm Outlook: This is an ongoing research project and after completion of the paper new material has already come to light or requires further research, such as mention of rib tools sharpened in a sickle fashion in a “slawic context”, citing personal communication with U. Schoknecht from Waren, Germany (Terberger 1996, 20 u. 30). Or edge tools from neolithic contexts of Switzerlannd and Germany made from pelvic bones, ribs or scapula (Steppan 2003; Schibler 1981). Anybody wishing to help shed further light on this issue by pointing out literature or offer support and cooperation is wellcome! Please contact the author at: markusklek@yahoo.com References cited can be accessed at http//:www.palaeotechnick.de/links....... Acknowledgements: I wish to thank Dr. Alice Choyke for providing the necessary data on the beamers from Hungary, for her enthusiasm for the project and for connecting me with others. Thank you to Dr. Mathias Seiffert and Dr. Karlheinz Steppan for reviewing the text and pointing me towards further material. Thank you also to Christian Küchelmann for transforming the file into a pdf and posting it on the WBRG website.