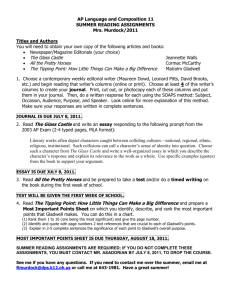

WENDY KOPP AND MALCOLM GLADWELL: “Teach for America

advertisement