THE CARBON-CARBON DOUBLE BOND

advertisement

NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION, THE CARBON-CARBON

DOUBLE BOND AND THE CHEMISTRY OF ALKENES

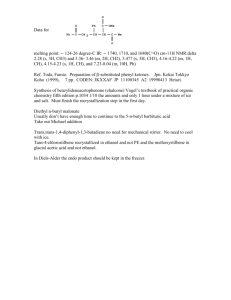

Text references: McMurry (5th Edition) Chapters 6, 7 and 11.

Some Important Definitions:

BASE: Any species that can 'accept' (i.e. form a bond with) a proton.

Since a proton has no electrons the base must be able to provide both

electrons for the proton-base bond. Therefore the atom in the base

which acts as the actual basic site must bear a lone pair of electrons.

The ease with which a base accepts a proton is referred to as its

basicity.

B : + H+

[ B:H ] +

NUCLEOPHILE: ('nucleus-loving') an electron-rich species with a

tendency to 'attack' (i.e. donate an electron pair to) an electron-poor site

in another molecule (called an ELECTROPHILE). The nucleophilic

site in many - though not all - nucleophiles will be an atom bearing a

lone pair of electrons.

The rapidity with which a nucleophile reacts with a given type of

electrophile is referred to as its nucleophilicity towards that kind of

electrophile. Good nucleophiles (high nucleophilicity) react rapidly

while poor nucleophiles (low nucleophilicity) react slowly.

Notice that a molecule behaving as a base (i.e. donating an electron pair

to a proton) is simply a special category of nucleophilic behaviour

where the electrophile is a proton.

Therefore a base is also usually (though not always) a nucleophile in

the more general sense. Strong bases are usually (though not always)

also strong nucleophiles and vice-versa.

Alkyl halides, RX, and related compounds are a group of very

important electrophiles in organic chemistry:

X

This carbon atom

is electrophilic

C

+

When alkyl halides react with nucleophiles two different kinds of

reaction can occur:

(1) Nucleophilic substitution:

X

C

+

Nu

+ Nu:-

C

+ X-

(2) Elimination:

X

C

- HX

C

H

-

:Nu

C

C

+ NuH + X-

Alkene

Here the nucleophile behaves as a base and removes a proton from a

carbon atom adjacent to the carbon bearing the halogen. The

consequence of the reaction is that the elements of a small molecule

(H+, X- = HX) are split out or eliminated from the alkyl halide and a

new compound with a carbon-carbon double bond is formed.

Nucleophilic substitution reactions:

Depending on the compounds involved nucleophilic substitution

reactions can involve one of two different kinds of stereochemical

change:

Consider the following reaction:

H

C6 H5

C

Br

CN

H

-

CH3

C

CN

C6 H5

CH3

(R)-1-Bromo-1-phenylethane

(S)-1-Cyano-1-phenylethane

The stereochemical configuration at the electrophilic carbon in the

starting material has changed from R- in the starting material to S- in

the product - the nucleophilic substitution occurs with an inversion of

configuration known, after its original discoverer, as the Walden

Inversion.

The kinetic behaviour of this reaction is also of significance. The rate

depends on both the concentration of the alkyl halide and on the

concentration of the nucleophile - i.e. the reaction follows a second

order rate law:

Rate = k x [RX] x [Nucleophile]

Second-order kinetics tell us that the reaction is bimolecular - i.e. two

molecules - the alkyl halide and the nucleophile - are involved in the

slowest (i.e. rate-determining) step of the nucleophilic substitution

reaction.

A mechanism accounting for the stereochemistry and kinetic

behaviour of this class of nucleophilic substitution reactions was put

forward in 1937 by Hughes and Ingold.

Hughes and Ingold labelled the process SN2 to indicate that it was a

substitution, involved a nucleophile and was bimolecular.

The crucial feature of the SN2 mechanism is that the nucleophile attacks

the electrophilic carbon from the rear of the group - called the leaving

group - which will be displaced. There is no intermediate - just a

single step in which the nucleophile forms a bond to carbon while the

leaving group departs:

H

N

C: Ph

C

Br

(R)-1-Bromo-1-phenylethane

Br

Transition state

CH3

N

C

H

C

Ph

CH3

H

N

C

C

Ph

CH3

+ Br-

(S)-1-Cyano-1-phenylethane

H

Nu-:

C

Ph

X

sp3

CH3

sp2

X

H

Nu

C

Ph

CH3

sp3

H

Nu

C

Ph

CH3

+ X-

As the nucleophile approaches it

repels the electrons in the bonds at

the central carbon forcing them

back in the direction of the

departing leaving group.

In the transition state the

hybridisation at carbon has

changed from tetrahedral sp3 to

planar sp2 with both nucleophile

and leaving group sharing an

unhybridised p orbital.

As the nucleophile moves even

closer to carbon - and the leaving

group moves off - the sp2

transition state collapses to sp3

again in the direction of the

departing leaving group forming

the substitution product with

inverted configuration at carbon.

The fact that both nucleophile and substrate are involved in the

transition state explains the bimolecular kinetics while the requirement

that the nucleophile attack from the rear of the departing leaving group

explains the inversion of configuration at the reacting centre.

Variables in the SN2 reaction

(1) Steric effects:

H

CH3

C

H

Br

C

H

H

CH3

Br

H

C

CH3

CH3

Br

CH3

H

Methyl

Primary

Secondary

2 x 106

4 x 104

500

High

C

Br

CH3

Tertiary

<1

Low

Relative SN 2 reactivity

As the degree of substitution on the halogen-bearing carbon increases

the reactivity towards SN2 substitution falls off dramatically.

Increasing substitution hinders the approach of the nucleophile to the

halogen-substituted carbon.

(2) The nucleophile:

H2O

Cl

HO

CH3O

1 x 103

HS

1 x 105

1.6 x 104

1

I

2.5 x 104

1.2 x 105

Weak

Powerful

Relative nucleophilicity (relative reactivity in S N 2 substitution)

(i) Nucleophilicity parallels basicity - stronger base = better nucleophile

(ii) Negatively charged nucleophiles are more reactive than neutral

(iii) For related species 4th row nucleophiles > 3rd row nucleophiles >

2nd row nucleophiles

An unexpected experimental result:

Relative SN 2 reactivity

High

Low

C

H

C

Br

H

H

R

C

Br

H

CH3

Primary

<1

1

R

C

Br

CH3

H

Br + H2 O

Methyl

Less

reactive

CH3

CH3

CH3

H

Br

CH3

OH + HBr

Secondary

12

Relative rate of reaction with water:

Tertiary

1.2 x 106

More

reactive

Q: How can this discrepancy be explained?

A: The one-step SN2 process is not the only possible reaction pathway nucleophilic substitution can also proceed by a two-step SN1

mechanism - unimolecular nucleophilic substitution - with a first order

rate law:

Rate = k x [RX]

Mechanism:

Slow

(CH3 )3C

Br

Rate-determining

step.

+

(CH3)3 C + Br

Rapid Nu-

(CH3 )3C

CARBOCATION

intermediate

Nu

Stereochemical consequences of the SN1 reaction:

H

+

Slow

C

Ph

H

Br

C

Ph

CH3

CH3

PLANAR

+ Br

sp2 hybridised

CARBOCATION

-

(R)-1-Bromo-1phenylethane

N

H

Ph

C

_

C

H

+

CN

CH3

(R)-1-Cyano-1phenylethane

50%

_

C

C

Ph

N

H

NC

C

CH3

RACEMISATION

Ph

CH3

(S)-1-Cyano-1phenylethane

50%

Where the SN2 mechanism leads to inversion at the reacting carbon

atom the SN1 mechanism leads to racemisation, i.e. to the complete loss

of optical activity .

Variables in the SN1 Reaction

(1) The structure of the substrate (i.e. the reactant which is attacked by

the nucleophile)

Energy

Transition State

Free energy

G‡

of

activation

R+ + X

Carbocation

intermediate

RX + Nu

RNu + X

-

Progress of reaction

Transition State Theory: Any factor which stabilises an

intermediate will also stabilise the transition state for the formation

of the intermediate and increase the rate of the reaction concerned.

So - what factors stabilise a carbocation?

H

CH3

CH3

CH3

C

C

C

C

+

H

+

H

H

<

Methyl

+

H

H

<

1°

+

CH3

CH3 CH3

<

2°

3°

Increasing carbocation stability

+

Filled C-H

bonding orbital

H

C

C

H

H

Hyperconjugation

Donating electrons

via -overlap to:

Empty p-orbital

of carbocation

H

CH3

C

H

H

Methyl

Less

reactive

Br

CH3

C

H

Br

H

Primary

CH3

C

CH3

Br

H

Secondary

Increasing SN1 reactivity

C

CH3

Br

CH3

Tertiary

More

reactive

Note that the structural factors which promote the SN1 pathway are

exactly the same factors which inhibit the SN2 mechanism.