Midterm Example # 2

advertisement

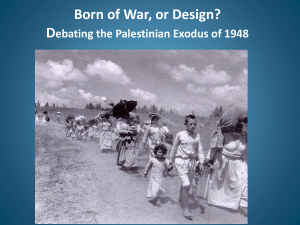

1 COMM 158 Midterm Essay 28 April 2015 The Palestinian Exodus of 1948: Born of War or by Design? Until recently, the debate regarding the origins of Palestinian refugeedom following the war in Palestine in 1948 drew on limited historical evidence and divergent narratives based on speculation of classified documents. However, in light of newly declassified military documents substantiating details of Israel’s early leadership’s direct and decisive involvement in the compulsory transfer of 700,000 indigenous Arabs out of Palestine, a new history of the events of 1948 is being written. At the center of this historical analysis is the question of pre-mediation: At the inception of the war, did the Zionist leadership have a preconceived design of expulsion as a means to make room for a Jewish majority in Palestine? The debate between historians Benny Morris and Nur Masalha rests on this issue of premeditation, which they both refer to as either the existence or nonexistence of a predesigned Zionist strategy for the transfer of Palestinians out of Palestine. In “Revisiting the Palestinian Exodus of 1948,” Morris describes a trend of ‘transfer thinking’ among Zionist leaders in the years preceding 1948; however, he makes a clear distinction between early discussion of ideas regarding transfer of the Arab inhabitants of Palestine and a designated policy for transfer in 1948. This argument supports a shared responsibility by two warring parties. In “A Critique of Benny Morris,” Nur Masalha asserts that this distinction between thought of transfer and designed transfer is factually deficient; he argues that evidence substantiating a concrete connection between overt Zionist support for transfer preceding 1948 and the results of Zionist political and military action during the war merely is yet to be declassified. Masalha criticizes Morris’ argument for inadequately recognizing accountability for Palestinian refugeedom on the part of Zionist leadership. By contrast, I argue that if the debate is centered on premeditation, we must first recognize that political responsibility on the part of Zionist leadership in 1948 need not be substantiated by the existence of a master plan for the expulsion of Palestinians. 2 Instead, ideological undertones throughout the Jewish population, in the wake of the Holocaust, inspired a collective understanding of the expulsion of the Palestinian people as a necessary and morally sound solution to establishing an exclusively, or at least predominantly, Jewish state; therefore, the resulting Palestinian exodus of 1948 was a culmination of preconceived Zionist goals, calculated action, and pervasive deflection of responsibility. Benny Morris’ historical narrative can be deconstructed into three main arguments: his assessment that the expulsions of 1948 were born of circumstances of war, his analysis of “transfer thinking” by Zionist leadership in the years preceding the war, and his conclusions that a direct relationship between thought and action of Zionist leadership is unsubstantiated by circumstance. He argues that the newly released documents reveal that the expulsions were “a product of the war, of the shelling, shooting, and bombing, and of the fears that these generated.” (Morris 37) Morris frames “the refugeedom of the 700,00 Palestinians” as a consequence of a war between two equally accountable warring groups; in essence, he is implying that it takes more than one military to fight a war, and so the responsibility for the outcomes of war are shared by all warring parties. Moreover, Morris argues that “the flight of the Palestinians” resulted from their defeat at the hands of incompetence and lack of readiness for war on the part of Palestinian leadership. He adds that the war created a state of economic disrepair in Palestinian communities, and this, coupled with encouragement from Zionist militias, inspired Palestinians to flee their homes. He deflects responsibility onto neighboring Arab countries for “failing at certain crucial junctures to give the Palestinians clear signals about whether or not to leave and, subsequently, by invading Palestine and then rejecting a succession of proposed compromises and by failing to absorb the refugees into their own countries.” (Morris 38) Morris refers to several independent and concurrent factors, such as Arab national involvement, specific to war events of 1948, all of which contribute to the ultimate denial of Zionist responsibility for the creation of Palestinian refugeedom. 3 Morris asserts that there was a clear “consensus or near-consensus in support of transfer – voluntary if possible, compulsory if necessary” amongst early Zionist leaders preceding 1948 (44). Yet, he reviews the transfer ideology as a passive setting for the development of the Palestinian expulsion of 1948 instead of an ideological blueprint with a causal relationship to the war. He writes that the discussion and support of transfer beginning in 1937 “conditioned the Zionist leadership, and below it, the officials and officer who managed the new state’s civilian and military agencies, for the transfer that took place.” (Morris 48) He argues that this pre-conditioning was fueled by “continuous anti-Zionist Arab violence” against a population of Jews still traumatized by the events of World War II. He frames the actual operation of transfer that took place as an action of necessity in which the survival of the Jewish people and their future state was at stake at the hands of the Arab aggressor. “After the Arabs of Palestine had initiated the war and after the Arab states invaded Palestine, that transfer was what the Jewish state’s survival and future well-being demanded.” Yet, this notion of transfer was merely a widely supported option that created “a mindset which was open to the idea and implementation of transfer and expulsion.” (Morris 48) Morris’ argument is contradictory in its premise; he portrays a decidedly passive “pre-conditioning” of transfer ideology as indication that the Zionist leadership was merely doing what it had to do for its citizens and is not accountable to their enemy yet denies a “direct, causal, one-to-one link between the earlier thinking and the subsequent actions.” (47) He implies that the only substantive link to be found would have to be a pre-existing policy on transfer set forth by Zionist leadership at the inception of the war. However, Morris confirms that even without evidence of a master plan, the Zionist militias displayed a pattern of action, far from “haphazard” when it came to atrocities in Palestinian villages and subsequent expulsion of the Palestinians from their land. In reference to a series of massacres beginning with orders from General Moshe Carmel, Morris argues that “two things indicate that at least some officers in the field understood Carmel’s orders as an authorization to carry out 4 murderous acts that would intimidate the population into flight: the pattern in the actions and their relative profusion; and the absence of any punishment of the perpetrators.” (54) While there is no evidence of written orders or a mass dispersion of this plan through military units, a lack of punishment against the perpetrators of these flight-inducing massacres produces uncertainty as to the level of leadership accountable for these atrocities. It is possible, as Morris himself articulates, that military and political leadership shied away from punishing those responsible for the civilian massacres in the event that “those charged would point an accusatory finger upwards, up the chain of command, to explain the source of their actions.” (54) This possibility lends support to Nur Masalha’s criticism of Morris’ argument. Nur Masalha, in “A Critique of Benny Morris,” argues that Morris’ insistence on the absence of a master plan for transfer relies on ignorance and attachment to the Zionist narrative. Masalha’s first critique of Benny Morris is that he relies on an insufficient, inconclusive selection of source material to substantiate prepossessed claims of a decidedly Zionist bias. Masalha argues that “generally speaking, having based himself predominantly, and frequently uncritically, on official Israeli archival and non-archival material, Morris’ description and analysis of such a controversial subject as the Palestinian exodus have serious shortcomings.” (91) This suggests an intentional component of misdirection in Morris’ assertions. Masalha adds that “while ignoring the recent works by non Zionist scholars on 1948,” Morris removes the debate from a discussion on the Palestinian reality to a hypothetical framework of Zionist thought and action (91). Masalha argues that it is possible that Ben-Gurion and lower-ranking members of the Zionist leadership in 1948 espoused an unwritten policy for transfer (92). Essentially, Masalha believes that the systematic, mass upheaval of the indigenous Arab population of Palestine is the apparent consequence of the Zionist leadership’s preconceived desire to accommodate for the growth of a Jewish majority in Palestine. Masalha shows that Morris’ ultimate reliance on Zionist narratives regarding the events 5 of 1948 is an ideological precedent that weakens his claims. For example, while Morris attributes the expulsions to exigencies of war and frames the Palestinian exodus as a mutual responsibility, Masalha reveals that the previously established Zionist goals for the creation of an exclusively Jewish nation naturally conditioned the indigenous Arab population for revolt. While Morris argues that mass transfer was necessary to the security of the Jewish state, Masalha contends that the “‘security’ threat posed by the ‘transferred’ inhabitants of the Palestinian towns and villages resulted from the Zionist movement’s ideological premise and political agenda, namely the establishment of an exclusivist state.” (Masalha 96) In other words, Morris relies on a narrative that justifies threatening the security of the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine in order to achieve the main goal of Zionist design. While Masalha’s argument is indeed weakened by his reliance on speculation of yet to be declassified Israeli military documents, his explication of Palestinian actions before and during 1948 suggests a direct connection between transfer thought, intention, and action on the part of Zionist leadership. It seems that, in both Benny Morris’ assertion that the Palestinian exodus was born of war and Nur Masalha’s understanding that it was a systematic Zionist design, there exists an all to narrow analytical framework. Both historians focus on a definitive connection between the thought of transfer and the actual expulsion of Palestinians in 1948 as the ultimate proof of premeditation and, subsequently, culpability. Like Masalha, I argue that Morris’ analysis reflects an explicit denial of responsibility on the part of Zionist leadership, yet I believe that proof of premeditation and causal responsibility rests in an implicit precondition that surrounds any possibility of premeditated transfer. The goals of the Zionist leadership in the years preceding 1948 reflected a collective understanding of the Jewish people that making the land of Palestine a permanent home was a precondition for security and survival. As a result of the inpouring of Jewish immigrants during the World War II era, the existing Zionist leadership in Palestine came to support compulsory transfer 6 as the optimal solution to establishing a Jewish majority in the future Jewish state. By 1948, the widespread advocacy of expulsion was integral to the Zionist expectations for establishing this Jewish majority. It is unnecessary to point to a master design as evidence of Zionist responsibility, when it is clear from the conditions for war that the Zionist leadership was ultimately responsible for the outcome of expulsion for the Palestinian people. The threat of transfer alone inspired growing resistance and violence in the Arab communities of Palestine, denoting a clear threat to the security of the Jewish population. It seems that what is missing from the Zionist narrative regarding the events 1948, that the return of diaspora Jewry to Palestine, despite being the imperative for the survival of a continuously persecuted people, is that it began an occupation of already inhabited land with displacement of the indigenous population as the indispensible outcome. In essence, the Zionist leadership, first with increased immigration to Palestine, then with the spread of ideology geared toward establishing a Jewish majority, and finally with the characterization of the Palestinian population as a threat to Jewish security, set the tone for a war in which transfer was the only possible means to an end.