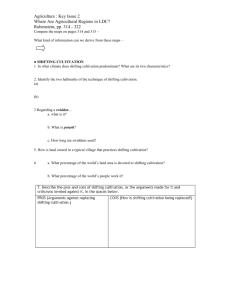

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ON

advertisement