Solutions to Questions and Problems

advertisement

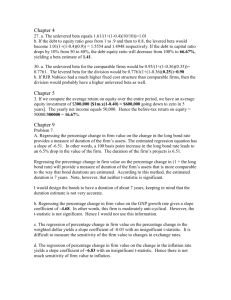

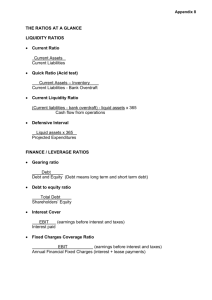

CHAPTER 13 LEVERAGE AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE Answers to Concepts Review and Critical Thinking Questions 1. Business risk is the equity risk arising from the nature of the firm’s operating activity, and is directly related to the systematic risk of the firm’s assets. Financial risk is the equity risk that is due entirely to the firm’s chosen capital structure. As financial leverage, or the use of debt financing, increases, so does financial risk and hence the overall risk of the equity. Thus, Firm B could have a higher cost of equity if it uses greater leverage. 2. No, it doesn’t follow. While it is true that the equity and debt costs are rising, the key thing to remember is that the cost of debt is still less than the cost of equity. Since we are using more and more debt, the WACC does not necessarily rise. 3. Because many relevant factors such as bankruptcy costs, tax asymmetries, and agency costs cannot easily be identified or quantified, it’s practically impossible to determine the precise debt/equity ratio that maximizes the value of the firm. However, if the firm’s cost of new debt suddenly becomes much more expensive, it’s probably true that the firm is too highly leveraged. 4. The more capital intensive industries, such as airlines, cable television, and electric utilities, tend to use greater financial leverage. Also, industries with less predictable future earnings, such computers or drugs, tend to use less. Such industries also have a higher concentration of growth and startup firms. Overall, the general tendency is for firms with identifiable, tangible assets and relatively more predictable future earnings to use more debt financing. These are typically the firms with the greatest need for external financing and the greatest likelihood of benefiting from the interest tax shelter. 5. It’s called leverage (or “gearing” in the UK) because it magnifies gains or losses. 6. Homemade leverage refers to the use of borrowing on the personal level as opposed to the corporate level. 7. One answer is that the right to file for bankruptcy is a valuable asset, and the financial manager acts in shareholders’ best interest by managing this asset in ways that maximize its value. To the extent that a bankruptcy filing prevents “a race to the courthouse steps,” it would seem to be a reasonable alternative to complicated and expensive litigation. 8. As in the previous question, it could be argued that using bankruptcy laws as a sword may simply be the best use of the asset. Creditors are aware at the time a loan is made of the possibility of bankruptcy, and the interest charged incorporates this possibility. 9. One side is that Continental was going to go bankrupt because its costs made it uncompetitive. The bankruptcy filing enabled Continental to restructure and keep flying. The other side is that Continental abused the bankruptcy code. Rather than renegotiate labor agreements, Continental simply abrogated them to the detriment of its employees. It is important thing to keep in mind that the bankruptcy code is a creation of law, not economics. A strong argument can always be made that making the best use of the bankruptcy code is no different from, for example, minimizing taxes by making best use of the tax code. Indeed, a strong case can be made that it is the financial manager’s duty to do so. As the case of Continental illustrates, the code can be changed if socially undesirable outcomes are a problem. 10. As with any management decision, the goal is to maximize the value of shareholder equity. To accomplish this with respect to the capital structure decision, management attempts to choose the capital structure with the lowest cost of capital. Solutions to Questions and Problems Basic 1. 2. a. EBIT Interest NI EPS EPS% $4,000 0 $4,000 $1.00 – 60 b. MV $80,000/4,000 shares = $20 per share; $35,000/$20 = 1,750 shares bought back EBIT $4,000 $10,000 $13,000 Interest 1,750 1,750 1,750 NI $2,250 $8,250 $11,250 EPS $1.00 $3.67 $5.00 – 72.8 ––– + 36.2 EPS% a. EBIT Interest EBT Taxes NI EPS EPS% b. MV $80,000/4,000 shares = $20 per share; $35,000/$20 = 1,750 shares bought back EBIT $4,000 $10,000 $13,000 Interest 1,750 1,750 1,750 EBT 2,250 8,250 11,250 Taxes 787 2,887 3,937 NI $1,463 $ 5,363 $ 7,313 EPS $0.65 $2.38 $3.25 – 72.7 ––– + 36.6 EPS% $4,000 0 4,000 1,400 $2,600 $0.65 – 60.1 $10,000 0 $10,000 $2.50 ––– $10,000 0 10,000 3,500 $ 6,500 $1.63 ––– $13,000 0 $13,000 $3.25 + 30 $13,000 0 13,000 4,550 $ 8,450 $2.11 + 29.4 3. a. b. c. 4. a. b. c. market-to-book ratio = 1.0, so TE = MV = $80,000; ROE = NI/$80,000 ROE .05 .125 .1625 – 60 ––– + 30 ROE% now, TE = $80,000 – 35,000 = $45,000; ROE = NI/$45,000 ROE .05 .183 .25 – 72.70 ––– + 36.6 ROE% No debt ROE .0325 .0813 .1056 – 60 ––– + 30 ROE% With debt ROE .0325 .1192 .1625 – 72.7 ––– + 36.3 ROE% Plan I: NI = $600K ; EPS = $600K/400K shares = $1.50 Plan II: NI = $600K – .10($5M) = $100K; EPS = $100K/200K shares = $0.50 Plan I has the higher EPS when EBIT is $600,000. Plan I: NI = $5.5M; EPS = $5.5M/400K shares = $13.75 Plan II: NI = $5.5M – .10($5M) = $5.0M; EPS = $5.0M/200K shares = $25.00 Plan II has the higher EPS when EBIT is $2,500,000. EBIT/400K = [EBIT – .10($5M)]/200K; EBIT = $1,000,000 5. P = $10M/400K shares bought with debt = $25 per share V1 = $25(400K shares) = $10M; V2 = $25(200K shares) + $5M debt = $10M 6. a. b. c. d. I II all-equity EBIT $12,000 $12,000 $12,000 Interest 3,080 1,540 0 NI $ 8,920 $10,460 $12,000 EPS $5.58 $5.81 $6.00 The all-equity plan has the highest EPS; Plan I has the lowest EPS. Plan I vs. all-equity: EBIT/2,000 = [EBIT – .11($28,000)]/1,600; EBIT = $15,400 Plan II vs. all-equity: EBIT/2,000 = [EBIT – .11($14,000)]/1,800; EBIT = $15,400 The break-even levels of EBIT are the same because of M&M Proposition I. [EBIT – .11($28,000)]/1,600 = [EBIT – .11($14,000)]/1,800 ; EBIT = $15,400 This break-even level of EBIT is the same as in part (b) again because of M&M Proposition I. I II all-equity EBIT $12,000 $12,000 $12,000 Interest 3,080 1,540 0 EBT 8,920 10,460 12,000 Taxes 3,390 3,975 4,560 NI $ 5,530 $ 6,485 $ 7,440 EPS $3.46 $3.60 $3.72 The all-equity plan still has the highest EPS; Plan I still has the lowest EPS. Plan I vs. all-equity: EBIT(.62)/2,000 = [EBIT – .11($28,000)](.62)/1,600; EBIT = $15,400 Plan II vs. all-equity: EBIT(.62)/2,000 = [EBIT – .11($14,000)](.62)/1,800; EBIT = $15,400 [EBIT – .11($28,000)](.62)/1,600 = [EBIT – .11($14,000)](.62)/1,800 ; EBIT = $15,400 The break-even levels of EBIT do not change because the addition of taxes reduces the income of all three plans by the same percentage; therefore, they do not change relative to one another. 7. I: P = $28,000/400 shares bought with debt = $70 per share; II: P = $14,000/200 shares = $70 This shows that when there are no corporate taxes, the stockholder does not care about the capital structure decision of the firm. This is M&M Proposition I without taxes. 8. a. b. c. d. 9. a. b. c. d. EPS = $5,000/800 shares = $6.25; Jimbo's cash flow = $6.25(100 shares) = $625 V = $80(800) = $64,000; D = 0.40($64,000) = $25,600 $25,600/$80 = 320 shares are bought; NI = $5,000 – .07($25,600) = $3,208 EPS = $3,208/480 shares = $6.68; Jimbo's cash flow = $6.68(100 shares) = $668 Sell 40 shares of stock and lend the proceeds at 7%: interest cash flow = 40($80)(.07) = $224 cash flow from shares held = $6.68(60 shares) = $401; total cash flow = $625. The capital structure is irrelevant because shareholders can create their own leverage or unlever the stock to create the payoff they desire, regardless of the capital structure the firm actually chooses. EPS = $19,000/1,000 shares = $19.00; Rebecca’s cash flow = $19.00(100 shares) = $1,900 V = $120(1,000) = $120,000; D = 0.30($120,000) = $36,000 $36,000/$120 = 300 shares are bought; NI = $19,000 – .08($36,000) = $16,120 EPS = $16,120/700 shares = $23.03; Rebecca's cash flow = $23.03(100 shares) = $2,303 Sell 30 shares of stock and lend the proceeds at 8%: interest cash flow = 30($120)(.08) = $288 cash flow from shares held = $23.03(70 shares) = $1,612; total cash flow = $1,900. The capital structure is irrelevant because shareholders can create their own leverage or unlever the stock to create the payoff they desire, regardless of the capital structure the firm actually chooses. 10. D/E = 1 implies 50% debt; VL = VU + TCD = $30M + .40($15M) = $36M D/E = 2 implies 67% debt; VL = VU + TCD = $30M + .40($20M) = $38M 11. With no debt the value is unchanged at $30M. D/E = 1 implies 50% debt; VL = VU + TCD = $30M + .30($15M) = $34.5M D/E = 2 implies 67% debt; VL = VU + TCD = $30M + .30($20M) = $36M Debt will increase the value of the firm more when the corporate tax rate is higher. 12. a. b. WACC = .16 = (1/2.5)RE + (1.5/2.5)(.11); RE = .2350 .16 = (1/2)RE + (1/2)(.11); RE = .2100 .16 = (1/1.5)RE + (.5/1.5)(.11); RE = .1850 .16 = (1)RE + (0)(.11); RE = WACC = .1600 13. a. b. c. d. all-equity financed: WACC = RE = .15 RE = RA + (RA – RD)(D/E) = .15 + (.15 – .09)(.25/.75) = .1700 RE = RA + (RA – RD)(D/E) = .15 + (.15 – .09)(.50/.50) = .2100 WACCB = (E/V)RE + (D/V)RD = .75(.17) + .25(.09) = .1500 WACCC = (E/V)RE + (D/V)RD = .50(.21) + .50(.09) = .1500 14. V = VU + TCD = $275,000 + .35($75,000) = $301,250 15. Interest tax shield = $42M(.38) = $15.96M. The interest tax shield represents the tax savings in current income due to the deductibility of a firm’s qualified debt expenses. 16. No taxes: VU = VL; value of the firm is $210M With taxes: V = VU + TCD = $210M + .40($70M) = $238M 17. E = VL – D No taxes: E = $210M – 70M = $140M, D/E = $70M/$140M = .50 With taxes: E = $238M – 70M = $168M, D/E = $70M/$168M = .42 18. Initially, RE = WACC = RA = .13 After issuing debt: RE = .13 + (.13 – .09)(1) = .17 WACC = .17(.5) + .09(.5) = .13 Intermediate 19. no debt: 50% debt: 100% debt: V = VU = $16,500(.62)/.18 = $56,833.33 V = $56,833.33 + .38(V/2) ; V = $70,164.60 V = $56,833.33 + .38V ; V = $91,666.66