תאריך:

advertisement

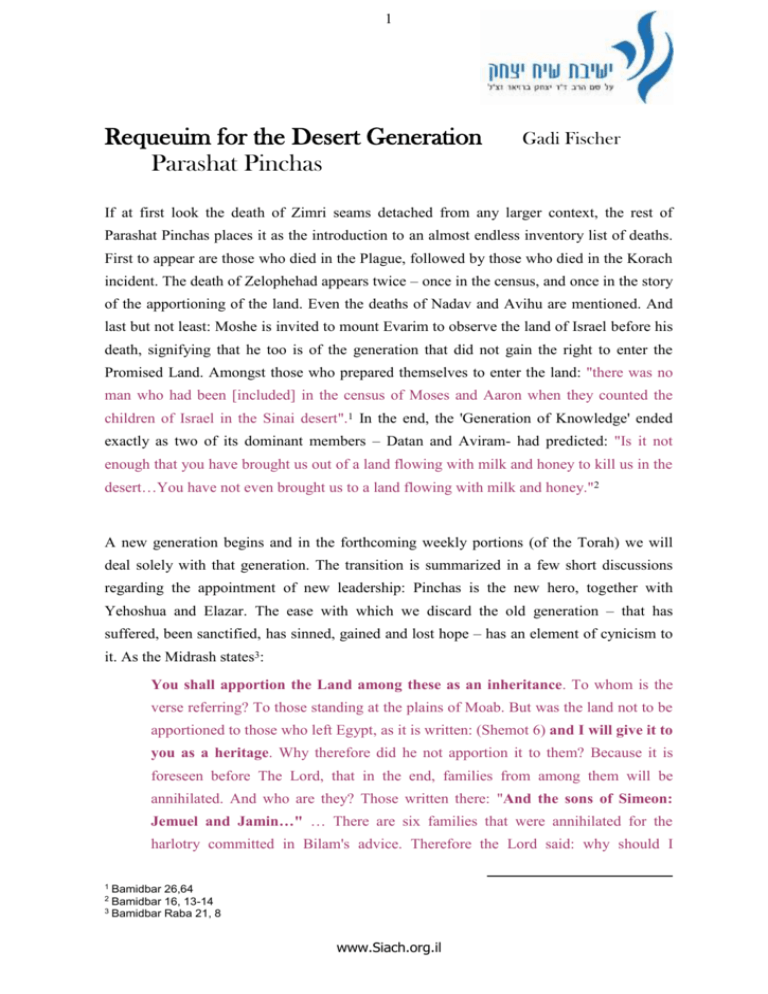

1 Requeuim for the Desert Generation Parashat Pinchas Gadi Fischer If at first look the death of Zimri seams detached from any larger context, the rest of Parashat Pinchas places it as the introduction to an almost endless inventory list of deaths. First to appear are those who died in the Plague, followed by those who died in the Korach incident. The death of Zelophehad appears twice – once in the census, and once in the story of the apportioning of the land. Even the deaths of Nadav and Avihu are mentioned. And last but not least: Moshe is invited to mount Evarim to observe the land of Israel before his death, signifying that he too is of the generation that did not gain the right to enter the Promised Land. Amongst those who prepared themselves to enter the land: "there was no man who had been [included] in the census of Moses and Aaron when they counted the children of Israel in the Sinai desert".1 In the end, the 'Generation of Knowledge' ended exactly as two of its dominant members – Datan and Aviram- had predicted: "Is it not enough that you have brought us out of a land flowing with milk and honey to kill us in the desert…You have not even brought us to a land flowing with milk and honey."2 A new generation begins and in the forthcoming weekly portions (of the Torah) we will deal solely with that generation. The transition is summarized in a few short discussions regarding the appointment of new leadership: Pinchas is the new hero, together with Yehoshua and Elazar. The ease with which we discard the old generation – that has suffered, been sanctified, has sinned, gained and lost hope – has an element of cynicism to it. As the Midrash states3: You shall apportion the Land among these as an inheritance. To whom is the verse referring? To those standing at the plains of Moab. But was the land not to be apportioned to those who left Egypt, as it is written: (Shemot 6) and I will give it to you as a heritage. Why therefore did he not apportion it to them? Because it is foreseen before The Lord, that in the end, families from among them will be annihilated. And who are they? Those written there: "And the sons of Simeon: Jemuel and Jamin…" … There are six families that were annihilated for the harlotry committed in Bilam's advice. Therefore the Lord said: why should I 1 Bamidbar 26,64 Bamidbar 16, 13-14 3 Bamidbar Raba 21, 8 2 www.Siach.org.il 2 apportion the land to those that are destined to die! Once they came to the plains of Moab… the Lord said: You shall apportion the Land among these. The process the Torah describes during the progression from the generation of the desert to those that entered the land, is familiar to us from various dynamics of child-parent relationships, as a relationship where the parents sacrifice themselves in different forms for the sake of their children and are destined to be discarded as an empty vessel. But maybe the temperamental attitude adopted by the generation of the desert prevented them from breathing the air of the promised land; maybe the emotional position of those who permit themselves to shout and insult – even if they are just – God and Moshe, doesn't allow them to listen to the silence of the land. Rabbi Tzadok of Lublin attempts to add an additional perspective in regard to the generation of the desert and their attitude toward torah and death. He reminds us (of the Rabbis' teaching) that they ceased to die on the fifteenth of Av4: The fifteenth of Av is actually the tragic day of the destruction of Tarmud, and therefore in this world, it is not yet clearly a 'Yom Tov', and it is not written as one in the Torah, and yet on that day those that were dying in the desert ceased to die. Tarmud is the opposite of Midbar [similar Hebrew letters]. Because that generation was rooted in the Torah they received on Mount Sinai, and death is from the complete opposite aspect, therefore on this day they were completely annihilated. In light of R' Tzadok we can understand that the generation of the desert was in essence a sort of union with an enlightenment that goes beyond any boundaries, and therefore cannot contain the cycles of normative life and death. Therefore they had to drain the temperamental spiritual aspects into spiritual procedures, which were disastrous for the most part. The un-checked braking of rules leads only to 'In this desert, your corpses shall fall'5. Perhaps one must come to terms with the most limiting mortality, in order to enter the Promised Land. 4 5 Dover Tzedek, 4 Bamidbar 14, 29 www.Siach.org.il