Narrative Practice and Identity

advertisement

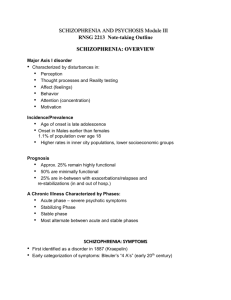

Constructing a “Schizophrenic” Identity Schizophrenia is one of the more incomprehensible conditions that afflicts mankind. It is hard to express just how cruel and tragic schizophrenia is both for individuals and for their families. It is estimated to affect approximately 1% of the population and occurs in normal, intelligent people in all walks of life. It occurs in every society and culture and has apparently been part of the human condition since ancient times. There have been many ways of talking about schizophrenia over the centuries: individuals were thought to be possessed by the devil or by witches, or in the grip of mysterious powers. Now, of course, we no longer think of the devil or witches. But over the course of the 20th century there have also been a number of ways of understanding schizophrenia: as a result of unconscious conflicts; as a creative response to an untenable family situation; as a sane response to an insane world; as a result of poor parenting or schizophrenigenic mothers; as a response to being labeled, and so on. Now, in the early part of the 21st century, the medical version of schizophrenia as a brain illness, “a broken brain,” (Andreason, 1984) has become the dominant, perhaps the only available, discourse for understanding schizophrenia. Certainly the medical discourse is hegemonic. Indeed, Shorter (1997) in his recent history of psychiatry describes the biological approach—“treating mental illness as a genetically influenced disorder of brain chemistry” (p. vii)—as a “smashing success” (p. vii). In this chapter, I examine the personal narratives of people with schizophrenia to show how people who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia use this medical discourse as a resource in the construction of identity. Although the medical discourse for understanding schizophrenia is, for all practical purposes, the only one available, and it would seem that individuals have very little choice in taking it up as a way to understand themselves and their 1 behaviour, it nevertheless is something that people actively do, rather than something that just happens to them. It is this active process of taking up medical discourse to describe experience that I examine here. I outline my theoretical approach to understanding how identity is constructed in personal narratives and then examine some extracts from interviews I conducted with people with schizophrenia to illustrate how the medical discourse is both taken up and resisted in the narrative construction of a “schizophrenic” identity. Narrative Practice and Identity Identity is an extremely complex construct that has been defined in a number of different ways in a variety of literatures (see Holstein & Gubrium, 2000 and Widdicombe, 1998 for detailed discussions). I draw here on a view of identity as narratively constructed and communicated (Holstein & Gubrium, 2000). As Rosenberg and Ochwald (1992) say, “Personal stories are not merely a way of telling someone (or oneself) about one’s life; they are the means by which identities may be fashioned” (p. 1). Gubrium & Hosltein’s (1998) notion of narrative practice elaborates this active process of identity construction and its relation to the social circumstances in which particular stories are told. They use the term narrative practice to “characterize simultaneously the activities of storytelling, the resources used to tell the stories, and the auspices under which stories are told” (p. 164). In this view, narratives are not simply reports of “the facts” of past or present experience. Rather they are artful, situated constructions assembled to describe and constitute, or ascribe meaning to, experience in particular ways. In an “interplay of discursive actions and the circumstances of storytelling” (Gubrium & Hosltein, 1998, p. 164), storytellers select from a vast memory storehouse of life events those aspects of experience that are relevant to a particular circumstance of storytelling and to the construction of a particular identity. 2 Personal narratives, however, are not simply individual productions; rather, they are, as Riessman (1998) puts it, “both an individual and a social product” (p. ?). Stories are mediated and constrained by the local and institutional circumstances of the storytelling and by available social and cultural resources, which people draw on to shape their stories, and their identities, in particular ways. Giddens (1991) uses the term institutional reflexivity to refer to the way in which what he calls abstract, or expert, systems provide people with material from which to construct identities. For Giddens (1991), to live in the context of institutional reflexivity is to actively engage in the filtering of expert knowledge into daily life, a process he calls “reskilling”(p. 7). Individuals appropriate expert discourses as a way to describe their own experience, something Giddens (1994) describes as “the very condition of the ‘authenticity’ of daily life” (p. 91). A diagnosis of schizophrenia provides an expert discourse through which people filter their lived experience. This expert discourse allows, and in fact requires, people to “redefine their past, present, and future in illness terms” (Karp, 1996, p. 63), using the expert knowledge provided by the medical system as a framework for the narrative construction of a “schizophrenic” identity. However, as both Giddens (1991) and Gubrium and Holstein (1998) point out, neither medical discourse nor local and institutional circumstances determine how individuals will construct identity. Rather all of these provide narrative resources, possibilities for who the self can be, that are actively taken up by individuals in diverse ways through interpretive practice. There is no doubt that the medical version of schizophrenia is a powerful discourse that limits the possibilities for self construction by exerting a strong degree of narrative control over those to whom it is applied. And in framing their own experiences in the language and understanding of the medical discourse, individuals reproduce and reinforce it as an appropriate resource for 3 understanding themselves. Nevertheless, within the limitations imposed by the discourse, individuals engage in interpretive activity and make choices about how and to what degree they will take up or resist the discourse. Giddens (1991) also points out that the way in which people take up medical discourse works back into the abstract system of expert knowledge, in turn reshaping it, although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to examine this process. I examine this interpretive activity in the construction of “schizophrenic” selves in the narratives of six people with schizophrenia. The narratives presented here were collected during a research project in which I conducted unstructured interviews with people with schizophrenia. The interviews were taped and later transcribed. Participants ranged in age from 18 to about 55. Four were women, two men. All had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and were taking medication to control their psychotic symptoms. Except for the 18 year old who still lived with her parents, they all lived independently, some of them working part time or attending school. Four were either married or living with partners. I examine three ways that the speakers in these narratives draw on the resources provided by the medical discourse of schizophrenia to construct identity. The first two of these have to do with how interviewees adopt medical language to describe their experiences, what Giddens (1991) would call reskilling: the acquisition of medical knowledge about schizophrenia, and the reconstruction of past experience in terms of this medical knowledge. These are closely related, although not exactly the same, and because they are difficult to separate in the narratives, I have combined them in the analysis. I then look at how interviewees resist the application of the medical discourse of schizophrenia to themselves. In my analysis, I show the narrative construction of identity in action. Adopting medical language to describe experience 4 In the following excerpts we can see medical language being used and medical knowledge being displayed as the speakers talk about their illness. In addition, we can see the way in which past experience or behaviour is actively reconstructed in light of knowledge provided by the medical version of schizophrenia. What once was a certain kind of experience and identity is now understood as another kind of experience and identity. Donald: (In response to a question about what he tells people schizophrenia is.) Yes, it’s a mental illness, a biochemical brain disorder with too much dopamine, and seratonin inhibitors are out of control. And then I would tell them that I have delusions, I have delusions and paranoia, but I never hear the voices or those things….I thought I did awful things, which I know I didn’t do now, but definitely at the time I thought I did awful things….Those delusions have been absent for about 2 years now. Donald uses a familiar vocabulary of dopamine and seratonin to describe schizophrenia as a biochemical brain disorder. He also talks of delusions, paranoia, and hearing voices. This is a vocabulary that many people will recognize in relation to schizophrenia. Readers might well ask if there is any other way to describe the symptoms of schizophrenia, attesting to the power and hegemony of the medical view of schizophrenia. But from the point of view of the person who is in the grip of schizophrenia and knows nothing of the medical illness schizophrenia, the experiences they have and their perceptions and understandings of the world are real. Donald thought he did “awful things.” He did not in fact do these things, but at the time he believed that he really had done them. Having been told, presumably by his medical practitioners, that they were not real, he has now learned to use medical vocabulary to describe these apparently real experiences as delusions and himself as a person who once had delusions. In a later excerpt, Donald again redefines past experience. 5 Donald: When I was young in college, I thought people thought I was really stupid because I couldn’t, chemistry experiments, physic experiments, I couldn’t do them because I was so slow and weighing things on scales and stuff like that. I couldn’t think it over because I got so nervous with people watching me, you know. I think people thought I was stupid, which I wasn’t. It was the illness. Here Donald describes real experiences, in which he was thought by himself and others to be slow and stupid. He had trouble doing lab experiements in university science classes and got nervous if people were watching him. Now he sees these experiences in a different light: it wasn’t that he was stupid, it was that he had schizophrenia. His narrative presents a person who once had certain kinds of thoughts about himself and told a certain kind of story about himself, but now has incorporated medical knowledge of schizophrenia into his personal biography to tell a quite different story about himself. He now has an identity as a person with schizophrenia rather than as a stupid person. In the next excerpt, Marie presents a veritable lecture about the involvement of the thalamus in schizophrenia. Marie: My perceptions are all different because the thalamus—do you know the brain is constructed to create this, the symptoms?…Well the thalamus generally is smaller. The thalamus is the relay center for all the perceptual experiences. So our thalamus, people with schizophrenia, the thalamus gets overwhelmed at times by the influx of perceptual experiences, which gets translated, because it can't take all the information in, it obscures it and it gets translated into these symptoms. Whether or not Marie is correct in her information is not the issue. Rather, we can see that she has incorporated this medical knowledge into her resources for understanding herself. She is a 6 person who has symptoms of schizophrenia because her thalamus gets overwhelmed by perceptual experiences. In the next excerpt we see her actively using this knowledge to understand and redefine her perceptual experiences. Marie: I also know that when these things called delusions are occurring in my mind, I can kind of separate myself from it. And if I can voice at some point, "This is too bizarre. Even though it seems very real, it's probably a delusion," you know, it's more manageable. She has experiences that seem quite real to her, but she now knows that some of her experiences are “delusions,” caused by an abnormality of brain function. When she has certain kinds of bizarre thoughts or experiences, she now actively defines them as delusions and “separates” herself from them, allowing her to manage these experiences and not let them interfere with her life. She is no longer a person who has true thoughts (at least some of the time), she is someone who can identify thoughts as delusions and manage them. In the next excerpt, Luanne describes the moment in which she redefined herself. Luanne: (Describing some pamphlets she read.) I remember feeling that way or thinking that way (referring to what she read), so that must have been part of it. Because I never realized how many symptoms I had, you know. I thought it was just that I heard this voice. But reading over the negative and positive symptoms, whoa, I had this and I had this, and those. Before reading the pamphlets about schizophrenia, Luanne thought of herself as a person who heard a voice. Then she read the pamphlets and suddenly aspects of herself that she had previously thought of as personal characteristics became symptoms of schizophrenia. In the time it took to read the pamphlets, she went from being a person who hears a voice to being someone whose personality and life experience were in large part symptoms of schizophrenia. She 7 constructs her present schizophrenic self from what the pamphlet directs her to notice in her past biographical particulars. From the point of view of the medical community, getting people to take up the medical discourse and agree that they have schizophrenia is seen as an important step in getting better. One of the hallmarks of schizophrenia is that people insist, in the face of their increasingly bizarre behaviour, that there is nothing wrong with them. It is only if people agree that they have an illness that they will participate in (or, in medical terms, comply with) treatment, which in the case of schizophrenia consists mainly of massive doses of extremely sedating medications with sometimes very troubling side effects. Taking on an illness identity is also very useful for people with schizophrenia themselves. Many have strange and frightening perceptual experiences and often engage in quite bizarre and anti-social behaviour. At the very least, their behaviour is different than it was before and this is usually very troubling for them and those around them. Using medical discourse to describe this behaviour helps both people with schizophrenia and those around them to make some kind of sense of these experiences and behaviour. In addition, socially unacceptable behaviour for which individuals would normally be held morally accountable is now redefined in terms of an illness over which they have no control. The construction of schizophrenic selves may be seen to serve the interests of individuals themselves, the medical community, and society at large. But that does not mean that it happens in an automatic way. In all of the excerpts presented so far, the speakers are people who actively participated in learning to present various aspects of their biographical particulars in the medical language of schizophrenia. In the next excerpts, the speakers actively resist medical discourse as a resource for identity construction. Contesting the Medical Discourse of Schizophrenia 8 The next speaker had demonstrated her ability to use medical language to describe herself throughout the interview. At one point she also said this: Jane: Yeah, I had a breakdown. I was diagnosed as a schizophrenic. I don’t feel very schizophrenic even though I know what schizophrenia is. Jane knows what schizophrenia “is,” according to the medical discourse, and she knows that the medical profession applies this label to her, but she confides that she still does not “feel very schizophrenic.” A psychiatrist listening to this statement would probably regard this as evidence that she does indeed have schizophrenia, because, as noted above, one of the signs of the illness is denial that there is any problem. However, it can also be understood as a statement by Jane that she is not willing to give herself over to the medical version of herself, and reserves the right and ability to define herself in terms other than those offered by the medical discourse. Jane here resists the totalizing power of the medical version of schizophrenia, perhaps only in her mind and expressed privately to me, but she resists none the less. In the next excerpt we see the speaker actively and explicitly resisting what she understands as the medical discourse of schizophrenia, instead drawing on what she regards as a more productive discourse in the construction of her identity. Marie: When I first went into the mental health system, when I was 19, I was told by a psychiatrist that I would never go to school, I would never work a job. Basically I would never live in the real world….Hearing that kind of information, it dispelled a lot of my hopes for a normal future. It was debilitating, actually. ….I actually believed that there was not a lot of future for me….The focus on the sick model as opposed to the able model is creating a lot of self-perceptions that the person is sick. 9 That's what I learned in community rehabilitation (a course she took at university)….That a disability is uniqueness, and you're not broken, you do not need to be fixed….They have a philosophy of self-actualization, how can a person become all they can be. Now that's not the focus with mental illness. The focus is on the problem. When you focus on the problem, then the person internalizes that they are a problem. They are ill. They are sick…. So now I find it's very fundamental to think of schizophrenia not as a problem. It's not a problem any more. I don't want to see myself as a problem. I want to see myself as somebody who is not unusual or bizarre, but as somebody who is unique….By removing myself from that identification, I know I have schizophrenia but I'm not going to consider myself as sick in the mind, I'm not going to make it a fundamental aspect of who I am. By doing that I think I'm going to develop and grow and integrate into this society more competitively than I would if I would be dependent on the system. That's a fact. In this stretch of talk, we can see Marie doing very explicit identity work. She does not deny that she has schizophrenia, which as noted above is a dangerous move for someone who has been identified as having it. Rather, she delicately negotiates her relationship to the medical version of schizophrenia. She identifies it as a way of talking about the self and contrasts it with other ways of talking about the self. She rejects the “sick” model for understanding schizophrenia and herself, selecting instead aspects of what she regards as an alternate model and discourse, the “able” model of disability discourse, as a resource for the construction of her identity. She regards herself as unique rather than sick or a problem, and believes that this will help her to be successful in integrating into society. In her narrative we can see how much autonomy 10 individuals can have in calling on various resources for self construction and just how active this process is. Conclusion My analysis shows that while larger cultural discourses, in this case medical discourse, are very powerful resources for identity construction, neither biographical particulars nor available discourses determine the self. People engage in what Holstein and Gubrium (2000) call “biographical work” in which they “assemble aspects of personal history that can be used to bolster present claims of and about” (p.169) themselves. Details of lives are “mobilized to become part of local-selves in-the-making” (p. 169). This is quite an ordinary process, something we all do all the time. And even though it seems that people with schizophrenia may have little choice in taking up a “schizophrenic” identity, it nevertheless is something they actively do, not just something that happens to them. Receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia does not mean that an individual must have a particular “schizophrenic” identity. Rather, both available discourses and past and present experience provide a set of resources that are actively taken up in various ways in the narrative construction of distinctive “schizophrenic” selves. While schizophrenia is a biological illness, it is also much more than a biological illness. It is very much a social phenomenon. I believe that understanding identity in the way that I have illustrated has implications for how schizophrenia is understood generally in society. In closing, I want to refer to the other half of Giddens’ (1991) ideas about reskilling, which were beyond the scope of this chapter to examine in detail: that changed social environments work back into expert systems in turn changing them. As Giddens (1991) show us, it matters how we take up the expert discourse, how we talk about schizophrenia generally, and the kinds of stories we tell when we talk to and about people with schizophrenia, because personal narratives feeds back 11 into that expert discourse, influencing and shaping it. Change in the expert discourse then affects how schizophrenia will be understood in future talk about it. This means that we have the potential to change how schizophrenia is understood generally in society and thereby to change the resources that are available to people with schizophrenia in constructing identity. And this opens the possibility for those of us who are lucky enough not to have schizophrenia to “provide those with schizophrenia better opportunities to participate more meaningfully and inclusively in the social world” (Doubt, 1996, p. xi). 12 References Andreason, N. (1984). The broken brain: The biological revolution in psychiatry. New York: Harper and Row Doubt, K. (1996). Towards a sociology of schizophrenia: Humanistic reflections. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge: Polity Press. Giddens, A. (1994). Gubrium, J. & Holstein, J. (1998). Narrative practice and the coherence of personal stories. Sociological Quarterly 39, 163-187. Holstein, J. & Gubrium, J. (2000). The self we live by: Narrative identity in a postmodern world. New York: Oxford University Press. Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis. Newbury Park: Sage. Rosenwald, G. C. & Ochberg, R. (1992). Storied lives: The cultural politics of selfunderstanding. New Haven: CT: Yale University Press. Shorter, E. (1997). A history of psychiatry: From the era of the asylum to the age of prozac. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Widdicombe, S. (1998). Identity as an analysts’ and a participants’ resource (pp. 191-206). In C. Antaki & S. Widdicombe (Eds.), Identities in talk. London: Sage. 13