English rhythm. Intonation is a language universal and its realization

advertisement

English rhythm.

Intonation is a language universal and its realization is inseparably connected with rhythm.

Intonation is a phonetic phenomenon, which is studied within the acoustic, auditory and functional language

aspects. The acoustic and auditory characteristics are combined within the perception level. The functional level

actualizes linguistic functions of intonation.

Intonation is a complex unity formed by significant variations of pitch, loudness and tempo closely related.

Pitch variations include significant moves of the voice up and down.

The degree of loudness determines the force of utterance and the prominence of words.

The tempo is determined by the rate of speech and the length of pauses.

Some linguists also mark speech timbre as the fourth component of intonation. It definitely conveys certain

shades of attitudinal or emotional meaning but there is no good reason to consider timbre alongside with three other

components of intonation, because it has not been thoroughly described yet.

It’s impossible to describe English intonation without reference to speech rhythm, because the interrelated

prosodic components (pitch, loudness, tempo) and speech rhythm are inseparably connected. Rhythm makes up the

framework of the spoken message.

A general term of ‘rhythm’ implies a regular recurrence of some phenomenon in time. Speech production is

naturally connected with the process of breathing, it is conditioned by physiological factors and is characterized by

rhythm. Rhythm as a linguistic notion is realized in lexical, syntactical and prosodic means, mostly in their

combinations.

Speech rhythm is traditionally defined as a recurrence of stressed syllables at more or less equal periods of

time in a speech continuum.

The type of rhythm depends on the language. There are two types of languages:

- syllable-timed languages (French, Spanish), which are based on the syllabic structure;

- stress-timed languages (English, German, Russian), which are based on the so-called ‘beats’ or

‘stress pulses’.

In syllable-timed languages the speaker gives approximately equal period to each syllable, no matter whether

it is stressed or unstressed. This produces the effect of even rhythm.

In stress-timed languages the effect of rhythm is based on units larger than syllable. The so-called ‘stress

pulses’ follow each other in connected speech at roughly equal periods of time, no matter how many stressed syllables

are between them. Thus the distribution of syllables within rhythmic groups is unequal and the regularity is provided

by strong ‘beats’.

The more unstressed syllables there are after a stressed one, the quicker they must be pronounced, for

example:

One

and

One

and a

One

One and then a

Two

and

Two

and a

Two

Two and then a

Three

and

Three

and a

Three

Three and then a

Four

Four

Four

Four

The peculiarities of English rhythm, implying the regular stress-timed pulses of speech, create the abrupt

effect of English rhythm. It has the immediate connection with such phonetic phenomena as vowel reduction and

elision, placement of word-stress and sentence-stress.

The effect of English rhythm is also presupposed by the analytical structure of the language. It explains

greater prominence of notional words and a considerable number of unstressed monosyllabic form words. The most

striking rhythmicality is observed in poetry.

Received Pronunciation.

Pronunciation is by no means homogeneous. It changes under the influence of numerous factors. There are

varieties of language phonetic means of different territoriality, which are conditioned by language communities

ranging from small groups to nations.

Received pronunciation (RP) is a living accent of the English language, It originally belongs to the Southern

accent group of British English, which is generally based loosely on the local accent of the south-east Midlands

(roughly London, Oxford and Cambridge).

RP is also a theoretical linguistic concept. It is the accent on which phonemic transcriptions in dictionaries are

based, and it is widely used for teaching English as a foreign language. RP has greater merit than any other English

accent and it provides us with an extremely familiar model accent. The phrase ‘Received Pronunciation’ was coined in

1869 by the linguist, A. J. Ellis, but it only became a widely used term used to describe the accent of the social elite

after the phonetician, Daniel Jones, adopted it for the second edition of the English Pronouncing Dictionary (1924).

The definition of ‘received’ conveys its original meaning of ‘accepted’ or ‘approved’ – as in the expression ‘received

wisdom’.

RP is probably the most widely studied and most frequently described variety of spoken English in the world.

In the course of language development RP became the pronunciation standard. The origins of RP trace back to the

public schools and universities of 19th-century Britain, when members of the ruling and privileged classes attended

boarding schools (Winchester, Eton, Harrow, Rugby) and graduated from the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

Their speech patterns soon came to be associated with ‘The Establishment’ and therefore gained a unique status,

particularly within the middle classes in London. Thus, the use of this pronunciation type had marked the speaker as

the representative of high society for a long time and had even been referred to as “King’s (Oueen’s) English”. The

spread of education gradually modified the characteristics of this accent in the direction of social standards. RP began

to be taught at public schools and used in the best society by cultured people. It was acknowledged as a social marker,

a prestigious accent of an educated Englishman.

RP has received its greatest impetus in 1922 when it became a broadcasting standard accent, which could be

the most widely understood variety of English, both in the UK and overseas. Such a decision clearly reflected the

social climate at the time. But it’s important to note that pronunciation standards are not permanently fixed and

undergo constant changes under the influence of various internal and external factors. These words are true for the use

of RP as well.

For much of the 20th century, RP has represented the voice of education, authority, social status and economic

power. Nowadays RP follows the modern tendencies when educational and social advancement suddenly became a

possibility for many more people. These also include the opportunities not to be under the linguistic pressure and thus

adopt the accent of the establishment or at least modify their speech towards RP norms. As a result, recent studies

suggest only 2% of the UK population speak RP. It has a negligible presence in Scotland and Northern Ireland and is

arguably losing its prestige status in Wales. It should be now best described as an English, rather than a British accent.

The wide distribution of radio and television caused considerable changes in the sound system of English, and

there appeared a new pronunciation model – the ВВС English. This pronunciation model greatly differs from the one

adopted in 1922 as a broadcasting standard. The pronunciation of the present-day professional BBC newsreaders and

announcers is based on RP, but also takes into consideration modern linguistic situation and thus becomes more

flexible and true-to-life. Moreover, the wide spread audio-visual means of mass communication make it accessible to

general public. The last editions of English Pronouncing Dictionary fixes the BBC accent as the most broadly-based

pronunciation model accent for modern English.

The remarkable systemic modifications in the standard can be mentioned both in the vowel and consonant

systems in the course of the last century.

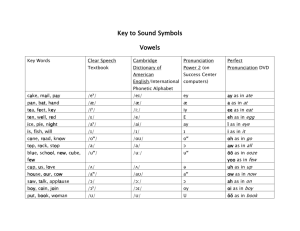

I. Vowel changes include the following:

1. increasing diphtongization of the historically long vowels [i:] and [u:];

2. frequent lengthening of a historically short vowel [æ];

3. gradual monophthongization of some diphthongs:

- [au], [aı] followed by neutral [ə] are smoothed (power [pauə] → [paə], fire [faıə] → [faə]);

- [εə] is levelled to long [ə:] (careful ['kεəful] → ['kə:ful]);

4. mutual vowel interchanges:

- between diphthongs [ou] and [əu] (phone [foun]/[fəun], note [nout]/[nəut];

- between monophthongs [æ] and [a] (have [hæv]/[hav], dance [dans]/[dæns]).

II. Consonant changes include the following:

1. gradual loss of the voiced/voiceless distinctions in certain positions:

- increasing devoicing of final voiced stops (dog [dog] → [dok], cab [kæb] → [kæp]);

- voicing of intervocalic [t] (letter ['letə] → ['ledə]);

2. loss of final [ŋ] and initial [h] in rapid speech (He saw her sitting there [hi· →so: hз· 'sıtıŋ ðεə] → [i: →so:

з· 'sıtın ðεə];

3. wide usage of typical elements of the American pronunciation:

- dark [l] instead of [l] (believe [bı'lıv] → [bı'lıv]);

- linking and intrusive [r] (faraway, the ideaof);

III. Combinative changes generally concern the pronunciation of [j] in certain phonetic contexts, which

include:

- loss of [j] before [u:] (student ['stju:dnt] → ['stu:dnt], suit [sju:t] → [su:t]), sometimes accompanied with

palatalization of the previous consonant (Tuesday ['tju:zdı] → ['t∫u:zdı]);

- intrusion of [j] before [u:] after [l] (illuminant [ı'lu:mınənt] → [ı'lju:mınənt]).

Thus, like any other accent, RP has also changed over the course of time. The voices we associate with early

BBC broadcasts, for instance, now sound extremely old-fashioned to most part of the British citizens.

Spread of English.

English is spreading throughout the world far more rapidly than any other language. However, it’s necessary

to underline, that modern English is not homogeneous at all and includes a great many of territorial varieties.

Territorial differentiation of the language is closely connected with social and cultural conditions and becomes the

basis of its division into national variants and regional dialects.

National language variants evolve from conditions of regional, economic, political and cultural concentration

which characterizes the formation of a nation. They may have considerable differences, but still they belong to the

system of one and the same language.

British English and American English prove to be the two main national variants of the English language and

serve the bases for the distribution of other national variants in the English-speaking world into: 1) the British-based

group, including English English, Welsh English, Scottish English, Irish English, Australian English, New Zealand

English; 2) the American-based group, including United States English, Canadian English.

American English and British English have separated more than a century ago. Nowadays these are the two

most widely used national variants of English, each of them possessing its own standards in all language systems.

There are two groups of pronunciation accents in British English - the Southern accent group and the Northern

and Midland accent group, which may be further divided into smaller groups of area accents, each of them consisting

of local accents. In the course of language development London local accent, belonging to the Southern accent group,

became the pronunciation standard. In the 19th century it was acknowledged as the Received Pronunciation (RP). Its

use marked the speaker as the representative of high society. The spread of education gradually modified the

characteristics of this accent in the direction of social standards. Received Pronunciation was taught at public schools

and used in the best society by cultured people. It has become a social marker, a prestigeous accent of an educated

Englishman.

Nowadays only about 2% of the population in Britain speaks RP, though it is still regarded as a conservative

model for correct pronunciation, particularly for educated formal speech. The wide distribution of mass media caused

considerable changes in the sound system of the English, and there appeared a new pronunciation model – the ВВС

English. This is the pronunciation of professional BBC newsreaders and announcers, which is based on RP, but also

takes into consideration modern linguistic situation and thus becomes more flexible and true-to-life.

The development of American English began with the settlement of the first British colonists in the North

American continent. In the course of its formation American English has undergone the influence of many other

languages, spoken by the Native Americans (the Indians), by the immigrants from Ireland, Spain, France, Holland,

Germany, by the Negroes. Nowadays the impact of Spanish and Chinese is easily felt in American English.

As for American pronunciation, it’s not homogeneous at all. Two types of pronunciation are distinguished –

Western pronunciation group and Eastern ans Southern pronunciation group.

The common feature for Eastern and Southern pronunciations is the absence of rhotic pronunciation. Besides

that, the Eastern type is characterized by linking and intrusive [r], initial [hw] (which [hwıt∫]), monophthongization of

diphthongs with [ə]-glide (fierce [fıəs] → [fi:s]). The Southern type is characterized by a specific ‘Southern vowel

drawl’ – diphthongization of pure monophthongs (egg [eg] → [εig], yes [jes] → [jeis]) and monophthongization of

original diphthongs (eight [eıt] → [ε:t], drain [dreın] → [drε:n]).

The Western pronunciation group includes the so-called General American type of pronunciation, which is

characterized by rhotic pronunciation or ‘Western burr’. This phonetic phenomenon includes either the pronunciation

of retroflexed vowels with r-colouring in the middle of the word (bird [bə:rd], worm [wə:rm], first [fə:rst], card [ka:rd],

port [po:rt]) or the pronunciation of retroflexed [r] in the final position (far [far], here [hıər]). Some linguists treat

General American (GA) as a standard pronunciation type, because it is spoken by the majority of Americans. But

many linguists state that no dialect can be singled out as an American standard, because different types of

pronunciation are constantly mixed and even professionally trained speakers retain their regional pronunciation

features.

The comparison of GA and RP makes it possible to define a set of peculiarities.

Segmental peculiarities include differences in the pronunciation of vowel and consonant phonemes:

- the absence of clear distinction between short and long vowels (sit/seat [sı·t], pull/pool [pu·l];

- rhotic pronunciation of vowels before [r] in all positions (turn [tə:rn], star [sta: r]);

- nasal twang – nasalization of vowels, preceded or followed by nasal consonants (stain, small, name);

- pronunciation of [æ] instead of [a] before a consonant cluster (class, after, path);

- pronunciation of [a] instead of [o] (dog, body) and a complete loss of long [o:] (cot [kat] vs caught [kot]);

- reverse pronunciation of [ı] and [aı] (civilization [ısıvılı'zeı∫n] → [lsıvılaı'zeı∫n], direct [dı'rekt] → [daı'rekt]);

- loss of [t] after [n] in the middle of the word (twenty ['twenı], wanted ['wonıd]);

- flapping – pronunciation of [t] like [d] in intervocalic position and before [l] (bitter, battle);

- the existence of only ‘dark’ shade of [l] (look [luk]);

- omission of [j] between a consonant or a vowel [u:] (news [nu:z], tube [tu:b]).

Supra-segmental differences generally concern the placement of stress:

1. the stress on the final syllable instead of the initial one in words of French origin (ballet [bæ'leı]);

2. the stress on the first element in compound words ('weekend, 'hotdog);

3. the existence of tertiary stress in polysyllabic words with suffixes -ory, -ary, -mony (laboratory ['læbrəltorı],

secretary ['sekrəltərı], ceremony ['serəlmonı]).

American intonation patterns on the whole is similar to that of RP. The differences generally convey

emotional and attitudinal meaning.