Robert Bage`s Hermsprong as a Historical Document

advertisement

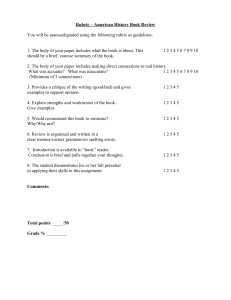

Robert Bage’s Hermsprong as a Historical Document Kevin P. Dugan Social Studies Department Plainview-Old Bethpage John F. Kennedy High School Bethpage, NY NEH Seminar 2006 Background Robert Bage (1728-1801) lived and worked in and around Birmingham and Tamworth in the English Midlands, where he witnessed (and participated in) a series of exciting economic, political, and cultural trends in English history. He owned and operated a paper mill at Elford in Staffordshire, and he was always intellectually curious and an avid reader. Bage visited Birmingham regularly, where he engaged in informal study and forged friendships with well-known figures such as Lunar Society members Erasmus Darwin and John Whitehurst. After an entrepreneurial iron works project operating in Wycher collapsed around 1782, and as his paper works faced continuing financial pressures (Perkins 15-16), he took up fiction writing, hoping that a supplementary career would distract him from financial anxieties (Hutton qtd. in Perkins 343). He is classified as a Jacobin novelist by most literary scholars (“Bage’s Books” 1) and published a total of six books. The English papermaking industry was on the cusp of major change during this final, literary phase of Bage’s career. In 1800 papermaking was still performed by hand, but a French innovation that used an endless wire cloth and a continuous felt blanket would be installed in Hertfordshire in 1803 (“History of Papermaking” 1), and a rapid series of patents and innovations and would follow, so that by 1809 the forerunners to the modern cylinder mould and vat machine were developed, and steam-heated drying cylinders would be in use by 1821 (“History of Papermaking” 1). Complex trends in the agricultural, manufacturing, commercial, and demographic domains, many of which are framed in different ways by different historians, reverberated through the Midlands and beyond in the late eighteenth century, and Bage developed strong opinions about the state of English society. He seems to assume a middle class female audience for his novels, and aims to introduce radical ideas of French 2 philosophes and Mary Wollstonecraft to his readers in the guise of light, if subversive, entertainment. But, just as interestingly, secondary plot developments allude to trends that interest historians of the Industrial Revolution. The novel is, of course, imaginative literature, and not a straightforward, declarative historical document. But Hermsprong helps the historian make sense of a radical, tradesman writer’s perspective on the early Industrial Revolution. The hero of the novel is a mysterious and compelling figure named Hermsprong, who was raised with Native Americans in what is now Michigan and, consistent with Rousseau’s principles, is thus is more attractive and virtuous than English men. He values friendship, forthrightness, generosity, and romantic love, and feels strongly about the harmful effects of hierarchy, nobility and hereditary privilege, conventional gender roles and patriarchy, rarefied etiquette, commercialism, and the influence of the Church of England. He travels throughout Europe by foot, with only one servant, and acts as a problem-solver whenever he can, often by dispensing money or consoling or befriending the unfortunate in a more or less chivalric way. Toward the end of the novel the reader learns his true identity: Hermsprong is the rightful heir to the aristocratic seat of Grondale, near Cornwall. His father was cheated of his title and fortune by a scheming, gambling, depraved, gout-ridden younger brother who now sits in the House of Lords, exploits his servants, tenants, and family members, and unjustly dominates the region with the aid of an arrogant magistrate-vicar, Dr. Blick. Hermsprong aims to eject the dishonest Lord Grondale and, through legal means, recover his title. But matters are complicated when Hermsprong falls in love with his uncle’s daughter. Hermsprong frequently speaks with his cousin, Caroline Campinet, her ebullient, troublemaker friend Charlotte Fluent and the narrator, Greg Glen about the natural equality of men and women and the mentally distorting effects of English tastes, gender and family structures. Bage’s characterization of the aristocratic villain is rich, effective, and entertaining. The description of Lord Grondale’s physical characteristics, sexual improprieties, egotism, betrayals, and his intention to forcibly marry his daughter, Caroline to an ugly aristocratic misfit are designed to outrage the reader. But the tone of the novel is light and upbeat, and while catastrophes nearly strike many characters, they 3 are almost always averted. In fact, in the penultimate chapter, the villain himself, as he lay dying of a stroke at home, seeks the forgiveness of his daughter and Hermsprong. With this resolution to the novel’s conflict, Bage implies in a discussion in the final chapter, Hermsprong’s region of Cornwall is set to enter a kind of utopian golden age, where tolerance and the rule of law will be the order of the day and unjust social hierarchy reduced, albeit within a framework that acknowledges property rights and Hermsprong’s preeminent social position. The novel advances a utopian vision of a simpler, more natural society. Bage thus shares, or anticipates, an interest of Robert Southey, who published his Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society thirty-four years after Bage finished Hermsprong. Both men are troubled by the new, commercialized English market economy, and both see a new avariciousness developing alongside technological and productive gains. The hero of the novel is aware of England’s urbanization and technological gains, but in an argument that anticipates Southey’s concerns, wonders about the net effects of the emerging economic order. You have built cities, no doubt, and filled them with improvement, if magnificence be improvement; and of poverty also, if poverty be improvement. But our question, my friend, is happiness, comparative happiness… It should seem… that nature in her more simplemodes, is unable to furnish a rich European with a due portion of pleasurable sensations. He is obliged to have recourse to masses of inert matter, which he causes to be converted into a million of forms, far the greatest part solely to feed that incurable craving known by the name of variety (Bage 158-159). Bage here seems to acknowledge the demand-driven source of England’s manufacturing momentum in the eighteenth century, just as Berg does in the Age of Manufactures, and, like Southey, he sees consumerism as alienating. In addition, both Southey and Bage express disapproval for the dismal science of economics (Bage 219), characterizing Malthus as in error, and favor the promotion of emigration as a policy that is in the public interest. Bage glorifies North America as a nobler, morally healthy environment, just as Southey ponders the advantages of settling in Latin America. The emigration issue is raised explicitly in the novel when Grondale’s attorney, Corrow, files a series of false or dubious charges against Hermsprong, including illegal advocacy for emigration. Bage and Southey thus share some common principles. But while Southey viewed the French 4 Revolution as a dangerous and misguided enterprise (even though he supported it initially), Bage takes a different view. Hermsprong is more or less sympathetic to the ideals of the French Revolution, and, given the geopolitical climate when it was published in 1796, placed Bage in potentially dangerous opposition with an ascendant reactionary political movement. His letters, as discussed by Perkins in the 2002 reprint of Hermsprong and, separately, in a brief obituary of Bage, written by his friend and principal paper customer, William Hutton in The Monthly Magazine in 1802, make it clear that Bage and his Birmingham milieu were traumatized by the anti-French (and anti-Dissenter) Birmingham Priestley Riots of 1791 (qtd. in Perkins 342-343). In the novel, the unlikable, elitist and selfserving Anglican minister Dr. Blick makes direct reference to the 1791 Birmingham attacks that affected Bage and his friend Hutton. Bage has Blick sound foolish as he slams dissenters, the idea of natural rights, and the value of tolerance in a sermon (164). Bage, Hutton, and their radical friends would have also been disturbed by the prosecution of speakers from the reformist London Corresponding Society in Birmingham in 1796 (Perkins 10). Bage himself, in his papers now at the Birmingham Library and discussed by Perkins, claims that the tax authorities harassed him for his political beliefs, even after he was cleared at a hearing (Perkins 13-17). Several historians, including the Hammonds in The Town Labourer, have argued that a proper analysis of economic and political trends during the early phases of the English Industrial Revolution cannot be conducted without considering the French Revolution, Britain’s wars with revolutionary and Napoleonic France, and the British state’s concomitant taxation and bond policies. According to the Hammonds, the newer entrepreneurial class and the older landholding classes collaborated in politics and oppressed (in unison) the new wage earning classes, in part out of fear of a popular proletarian insurrection inspired by the French Revolution. The classes that possessed authority in the State and the classes that had acquired the new wealth, landlords, churchmen, judges, manufacturers, one and all understood by government the protection of society from the fate that had overtaken the privileged classes in France (320). The Hammonds, while they allow for exceptional elite figures who advocated for the working classes, see a class conflict underway during Bage’s lifetime, and the power of 5 the pre-reform state was usually deployed against the wage earners. Bage himself seems to deploy a class formulation similar to that used by the Hammonds. The narrator of the novel, Hermsprong’s friend, Greg Glen, recounts Lord Grondale’s reaction to a letter from the titled and wealthy Henrietta Chestrum, in which Chestrum lays out her family’s pedigree and wealth, and suggests that her son marry Grondale’s daughter, Caroline. There was something in this letter, which a plain man of common sense and excitable lungs might have laughed at; but to the noble sentiments of the noble lord to whom it was addressed, it was perfectly congenial. I understand that in this island of Great Britain, at the time I am now writing, birth is the first virtue, and money the second; some indeed may dispute the precedence; but all will allow that one or both aresine qua nons, without which virtue is not (227). Here the novel explicitly (and critically) addresses class. Bage’s fiction, while entertaining, was at the same time radical and anti-establishment. The political agenda of Hermsprong thus placed Bage in direct opposition to the business and landholding elites of his day. The novel’s treatment of two legal figures, the magistrate Dr. Blick and Grondale’s attorney, Corrow, resemble the Hammonds’ treatment of abusive local magistrates. Both the Hammonds and Bage take note of the way local judicial proceedings can deviate from common law principles in favor of the maintenance of elite privilege. In one section, Corrow considers what tactics he could use to spuriously convict Hermsprong. Mr. Corrow had a prodigious respect for Lord Grondale, and for money; and would have done for one, or both of them, any thing or every thing that the law, in all its latitudes, would have enabled him to do. To press down to the earth, and under it, a poor man, is easy; it is the work of every day; but to make a man, with money in his purse, guilty of crimes he never committed, requires a superior fund of knowledge (Bage 226)… The novel’s treatment of elite manipulation of the local legal system anticipates the Hammonds’ discussions of unjust magistrates like Colonel Fletcher of Bolton (Hammonds 65) and the Vicar of Chudleigh (Hammonds 72). In fact, the Hammonds’ discussion of the latter figure bears a striking similarity to Bage’s Corrow in that both legal actors sought to prosecute their targets on the basis of possession of Thomas Paine books which Bage would probably endorse. 6 Bage deals directly with the issue of French radicalism in Hermsprong, and we see, for example, Hermsprong declining to criticize the French Revolution when baited by other characters. The hero of the novel is later accused by Lord Grondale and his legal agent, Corrow, of being a French agent. Hermsprong’s powers of verbal persuasion, and the professionalism of the magistrates other than Dr. Blick, yield an outcome of not guilty on that charge (and the others, too). Here Bage’s social vision appears to diverge from the Hammonds’, but only slightly. While unsavory characters like Corrow and Blick, corrupted and eager to please Grondale, aim to manipulate the English legal system, they are repeatedly rebuffed by Hermsprong, and the system overcomes the attempts to manipulate it. The Hammonds, having analyzed relevant Home Office papers, convey a sense of local legal dysfunctionality in The Town Labourer. But both Bage and the Hammonds seem to agree that the poor working people generally do not prevail in the legal system when their interests are at variance with those who are wealthy. Bage’s unfriendly and satirical treatment of Lord Grondale, Dr. Blick, and Sir Philip Chestrum, the ugly, mean-spirited, ridiculously class-conscious failed suitor to Caroline Campinet, are the most obvious devices used by Bage to challenge the dominant political discourse. While the novel does not assign much attention to exploitative, entrepreneurial characters, we know that Lord Grondale accumulates capital from the mining operations on his lands, that he collects rents and government bond interest payments, and repeatedly attempts to manipulate the courts. His behavior, then, is consistent with the Hammonds’ framework, and Grondale’s financial portfolio takes into account the new commercial economy, which Bage dislikes. Manufacturers and businessmen do appear in the novel, but only in the background. Bage does not develop these characters or direct at them the kind of venom reserved for the older, landholding elite class, with their legal and Church lackeys. A textile magnate, for example, successfully courts the attractive Miss Brown early in the novel, and the widowed Mrs. Garnet, who is rescued from loneliness and poverty by Hermsprong, was married to a failed merchant who died en route to the West Indies to rebuild his failed business. A French textile magnate, Rupre, does receive negative attention in the novel, as he seeks to stop the marriage of his daughter and Hermsprong’s father by placing her in a convent and then, after the marriage, refuses to communicate with her. This sub-plot parallels the 7 more central, despicable treatment of Caroline Campinet by Lord Grondale and reinforces the novel’s emphasis on gender and the value of romantic love. Given Bage’s background, one might not expect him to pursue an antiestablishment literary agenda. He associated, after all, with some of Birmingham’s premiere businessmen. But Hobsbawm puts forward a class framework for the early English Industrial Revolution that allows for the performance of subversive advocacy work by someone, like Bage, who employs workers, owns property, and associates with men like William Hutton, Erasmus Darwin, and John Whitehurst. An important group had even accepted, indeed welcomed industry, science and progress (though not capitalism). These were the ‘artisans’ or ‘mechanics’, the men of skill, expertise, independence and education, who saw no great distinction between themselves and those of similar standing who chose to become entrepreneurs, or to remain yeoman farmers or small shopkeepers: the body of men who overlapped the frontiers between working and middle classes. The ‘artisans’ were the natural leaders of ideology and organization among the labouring poor, the pioneers of Radicalism (and later the early, Owenite versions of Socialism), of discussion and popular higher education… And a variety of clubs, societies and freethinking printers and publishers… (68). Hobsbawm, like the Hammonds, develops a framework of class exploitation and the extraction of capital from the workers who create it. Industry and Empire takes note of a class of men who are betwixt and between two social worlds, with conflicting loyalties. Bage’s biographical profile matches Hobsbawm’s model, and he clearly pursues a populist tone in his letters and many of his novels (Kelly 1). Hermsprong, however, would probably disappoint Marxists as a revolutionary document, since it never directly tackles questions about the means of production or labor specialization, fails to advance anything like a national or broad-based program for change, and instead seems to imply, optimistically, that England’s social ills and faults can be resolved at the local and interpersonal levels, outside the political stage. When the characters engage in conceptual reasoning, they discuss some ideas associated with Wollstonecraft, Voltaire, and Rousseau. Family and individual conduct and ethics, not institutional ones, dominate the more intellectual dialogues in the novel. While elite figures are at the center of the plot, wage earners and other workers do appear, and their portrayals are worth noting. Early in the novel, the narrator, Greg Glen, 8 explains that his mother was a cottager who was seduced by a local lawyer and died in childbirth (Bage 59). Here Bage, however briefly, addresses rural social conditions in the late eighteenth century and alludes to the distressed marginal (and landless) classes who lost access to common pastures during the Enclosure Movement. Later, in Grondale, near Cornwall, a terrible storm strikes, and several buildings are damaged or destroyed. There are even some fatalities. Hermsprong’s love interest, Caroline Campinet, describes the hero’s reaction to the crisis to Dr. Blick. Here is a gentleman has been amongst the cottagers, ever since the dawn of day. All the labourers are at work to repair their respective damages. He promises their usual pay to all, and a gratuity over to those he finds most industrious. In the mean time, the butcher is stripped of meat (Bage 136)… Here the rural poor appear as the victims of a natural disaster, and they are mobilized by a generous, rational leader. The workers are faceless, but diligent and responsible, and their conduct was determined by the influence Hermsprong exerted over them. Throughout the novel Hermsprong succeeds at gaining the support of ordinary people in a way that Lord Grondale and Dr. Blick cannot. Perhaps the most interesting example of Hermsprong’s interaction with working men occurs later, when a mining strike takes place within the boundaries of Lord Grondale’s properties. The mineral they extracted is not identified, but eighteenth century Cornwall ranked among the world’s biggest producers of copper and tin (Jowell 1) and, in Bage’s lifetime, Newcomen’s atmospheric (or ‘beam’) engines—symbols of modernity and technological innovation-- dotted Cornwall, where they were used to pump water from mines (“Mine Steam Engines, Cornwall” 1). The more efficient Watt-type engines were just beginning to appear at the time the novel was published (“Mine Steam Engines, Cornwall” 1). The novel cites “dearness of provisions” as the trigger for the labor action (Bage 307), and Perkins, in her annotations to the novel, discusses the food riots and shortages in 1795 as a likely inspiration for the fictional incident (Perkins 307). The crowds of rioting miners were growing by the day and they threatened violence against the exploitative classes. Their critics in the establishment suspected support from France. They were coming to pull down all lord’s houses, especially Lord Grondales’s; for he was a miner; had gotten rich by the sweat of their brows, and for any good he had ever done, they never heard of it (Bage 307). 9 Another crisis rocks the community, and again a paternalistic Hermsprong dramatically springs into action. The reader learns what happens through the testimony, at trial, of a “junior justice of the bench” who observed events and presented Hermsprong in a favorable light. The junior justice appeared before the miners, directing them to disperse. But then Hermsprong addressed the workers. My friends, perhaps it may be that your wages are not adequate to the furnishing you with all the superfluities of life which you may desire; but these are unhappy times, and require of you a greater degree of frugality and forbearance. My friends, we cannot all be rich; there is no possible equality of property which can last a day. If you were capable of desiring it, which I hope you are not, you must wade through such scenes of guilt and horror to obtain it, as you would tremble to think of. You must finish the horrid conflict by destroying each other. And why should you desire it? The rich have luxurious tastes and disease; if you have poverty, you have health (Bage 314). But before Hermsprong finishes, he was interrupted by a miner who asked the mysterious hero who he was and accused him of being a “royal spy.” Hermsprong punches the man in the head, but then apologizes and offers a half crown as a de-escalation gesture. He explained that he was bothered by the insinuation that the king should not be respected, but the punch appeared to raise Hermsprong’s standing among the miners. Hersmprong then sets up a sort of relief fund, delegating to a man in the audience the power to disseminate funds from a bag of silver as a means of covering essential food costs for miners unable to feed their families. The hero resolves the crisis, and the recounting of events at trial boosted Hermsprong’s standing vis-à-vis the panel of magistrates. The mining strike incident raises interesting questions about Bage’s political ideas and could lead one to question the argument that he identified with working people. The miners are depicted as blustery brutes who can listen and come close to appreciating a reasonable argument, but need additional nudges like the spectacle of a public punch or the offer of money to behave maturely. Many modern readers are likely to find the miners’ logic—“that others had gotten rich by the sweat of their brows”-- sounder than the hero’s assertion that poverty is ennobling and healthier than affluence. It appears that Bage is using the incident as a vehicle for exploring Rousseau’s ideas about the state of nature with his assumed middle class female audience. The treatment of the incident is not subversive at all, and seems to support the maintenance of property rights, even 10 during famines. Still, Bage seems to imply that it is unreasonable to assume that the labor actions of his lifetime (and, more broadly, participation in combinations or unions) are always tied to a French fifth column. Bage also conveys a sense that working people could, conceivably, receive wages that would not cover bread costs, as Tilly and Scott document, and he may have thought that would be a revelation to his assumed audience. No women appear in this scene of the novel, even though Tilly and Scott sketch a model for bread riots in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that emphasizes female leadership (Tilly and Scott 55-56). Most plot development occurs in Grondale’s section of Cornwall, and it is interesting to compare and contrast Bage’s description of events there with Charles Dickens’ depiction of 1854 Coketown in Hard Times. Dickens’ Coketown is, economically, more advanced than Bage’s own protoindustrialized Birmingham, and even more so, the fictitious, mostly agricultural and mining section of Cornwall in Hermsprong. The division of labor would be more elaborate and rational by the midnineteenth century, and the organization of workshops and factories would be much more regimented and more closely supervised by the capitalist investor or his hired managers. According to Berg, the toy manufacturing sector that drove Birmingham’s growth during Bage’s lifetime was varied, dynamic, technologically innovative, and favored mediumsized workshops with a wide range of organizing structures, all interfacing with an elaborate web of factors, merchants, county dealers, and shopkeepers (Berg 288-305). On the other hand, the Dickensian Coketown, like the historical Manchester of Dickens’ day, makes much fuller use of coal-fueled steam power than the metals manufacturing and other workshops of Bage’s late eighteenth century Birmingham, and the labor force was fully proletarianized. The scale of the factories was much larger than the metals workshops of 1790, and women and children were deployed differently. Coketown, as described by Dickens, was a dark, depressing, dehumanizing place, especially for the working poor, but also the two children of the relatively affluent Thomas Gradgrind. Gradgrind’s rigid, cold-hearted devotion to liberal economic and technocratic utilitarian thought and Bounderby’s emphasis on a dishonest and warped theory of self-reliance and social mobility are both exposed as fallacious. Dickens’ Stephen Blackpool declares the social and economic system of Coketown a real 11 “muddle,” and the novel presents an essentially nihilistic vision of life in the new factory cities. The setting for Hermsprong is also socially warped, in part by deleterious factors such as commercialism, classism, outmoded gender concepts, and unjust customs. But a single character, Lord Grondale, embodies the worst of the vices that trouble Bage, controls the means of production, and seeks to dominate local affairs. His function is similar to Bounderby’s; both hegemons believe strongly in their superiority and are mocked by the novelists who create them. But Bounderby is a replaceable cog in the capitalist system, while Grondale’s ejection from the political and economic system, Bage seems to think, could yield a just outcome. Interestingly, the two rich men’s relationships with their respective domestic managers, namely Bounderby’s Mrs. Sparsit and Grondale’s Mrs. Stone, are rich and complex. In both cases the employed woman understands her employer better than anyone else and sets the tone for the home until a falling out occurs. Curious psychological (and in the Grondale-Stone relationship, physical) intimacies and conflicts occur. The two pairs of couples constitute a type of family unit, as sketched by Tilly and Scott, although in both cases they collapse. In the case of Sparsit, her privileged family background provides Bounderby with an oddly pleasurable touch of social sophistication, while the illicit sexual nature of the Grondale-Stone relationship is grotesquely hypocritical, given Grondale’s conservatism and pretensions of superiority. Dickens does create an analogue to the Rousseauean Hermsprong in Sissy Jupe. Like Hermsprong, she is refreshingly free of oppressive customs and inhumane ways of thinking. In Hermsprong’s case, outmoded customs and hierarchies are frustrating, and he works toward pulverizing them at the local level. Sissy, too, does not identify with the dominant ideology, although in her case she is steering clear of a new set of ideas— utilitarianism—and not the holdovers of the medieval past. But Sissy does not take any political action, and limits her efforts to acts of kindness within the Gradgrind household. Her mode of leadership, if one can call it that, is quiet and unlikely to change the system, while Hermsprong’s actions are politically disruptive, at least in Cornwall. Both novels paint a picture of dysfunctional socioeconomic systems. Dickens declares Coketown a muddle and rejects religion, laissez-faire economics, utilitarianism, 12 trade unions, and political reform. Hermsprong, on the other hand, is more optimistic. True, the culture and economy have perverse elements, but heroes like the charismatic, romantic Hermsprong, through the powers of reason and persuasion and the effective use of money, can expose the defects of the current system and introduce a more just order. The likes of Grondale can be humilated and weakened, as occurs when the court system finds against him, in spite of his hereditary privileges. For Bage, Enlightenment principles, including reason, can provide solutions to social injustice. Works Cited Bage, Robert and Perkins, Pamela, ed. Hermsprong. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview, 2002. Berg, Maxine. The Age of Manufactures. New York: Oxford UP, 1986. British Association of Paper Historians. “History of Papermaking in the United Kingdom.” British Association of Paper Historians Website. [http://www.baph.org.uk/general%20reference/history_of_papermaking_in_the_u nited%20kingdom.htm, accessed August 12, 2006] Cornwall Calling. “Mine Steam Engines, Cornwall.” Cornwall Calling (Tourist Website.) [http://www.cornwall-calling.co.uk/mines/steam-engines-mines.htm, accessed July 24, 2006] Dickens, Charles and Spector, Robert David, ed. Hard Times. New York: Bantam, 1981. Hammond, J.L. and Hammond, Barbara. The Town Labourer: 1760-1832, The New Civilization. London: Longmans, 1917. Hobsbawm, Eric. Industry and Empire: The Birth of the Industrial Revolution. New York: New Press, 1999. Jowell, Tessa. “Mining Landscape of Cornwall and West Devon Becomes a UNESCO World Heritage Site.” London: Ministry of Culture, 2006. [http://www.chymor.com/worldheritage.htm, accessed August 3, 2006] Kelly, Gary. “Bage, Robert (1728?–1801)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, May 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1028, accessed July 24, 2006] 13 Revolutionary Players Project. “Bage’s Books,” Revolutionary Players, [http://www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk/home.stm (“People” section), accessed August 3, 2006]. Revolutionary Players Project. “Practical Utopias: the Writings of Robert Bage.” Revolutionary Players. [http://www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk/home.stm (“People” section), accessed August 3, 2006]. Revolutionary Players Project. “A Biography of Robert Bage.” Revolutionary Players. [http://www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk/home.stm (“People” section) accessed August 3, 2006]. Tilly, Louise and Scott, Joan. Women, Work, and Family. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1978. 14 RELEVANT IMAGES A first edition of Bage’s Hermsprong (1796). Antiquarian Booksellers of America at http://www.abaa.org/cgi-bin/abaa/abaapages/index.html 15 Bage’s home—the Millhouse at Elford-- as it appears now. Photograph by John Goss. From Revolutionary Players at http://www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk/people.stm 16 Watercolor by T. Fornet, from Buckland Churchyard. A Dover paper mill at Buckland, 1799. This mill operated at the same time as Bage’s. British Association of Paper Historians, http://www.baph.org.uk/imagepages/quarterly/q49p23.htm Also available at http://homepage.ntlworld.com/g.hatfield1/pic1770.htm 17 A papermaker at work. Papermaker, The Book of Trades or Library of Useful Arts, Part III, third edition (London Tabart and Co, 1806). From Revolutionary Players at http://www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk/people.stm