The expression of semantic and pragmatic distinctions in children`s

advertisement

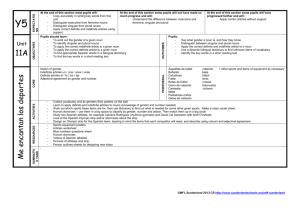

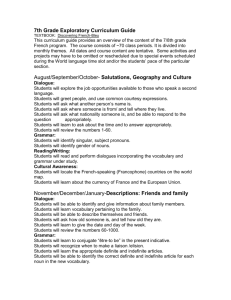

The emergence of article functions in a German-Italian bilingual child: Steps towards morpho-syntactic explicitness* Tanja Kupisch University of Hamburg, Research Centre on Multilingualism 1. Introduction Articles, although they are function words, appear relatively early in children’s speech production. Most Italian-learning children have been shown to produce articles or articlelike fillers several months before their second birthday (e.g. Pizzutto and Caselli 1992, Bottari, Cipriani & Chilosi 1993/1994, Antelmi 1997). German-learning children, by contrast start to produce articles only towards the end of their second year or even later (see Lleó 2001, Kupisch 2004). Article omission in obligatory contexts tends to decrease below the level of 10% before the children reach their third birthday (e.g. Chierchia, Guasti and Gualmini 1999, Pizzutto and Caselli 1992, Caselli Leonard, Volterra and Campagnoli 1993, Kupisch 2004 for Italian1; Penner and Weissenborn 1996, Eisenbeiss 2000, Kupisch 2004 for German). Depending on the target-language, it may take a long time until the full morphological paradigms are acquired. For instance, the three Italianlearning children examined by Pizzuto and Caselli (1992) started to produce articles before they reached their second birthday, but only for the feminine singular form la the acquisition criterion of correct suppliance in 90% of all obligatory contexts was reached before age 3;0 by all children. This work attempts to go beyond a quantitative description of article use, and it will not be concerned with the acquisition of the morphological functions gender, number, and case either. Rather, it deals with the question whether article forms are used in variation to encode semantic and pragmatic functions; i.e. functions which are related to (i) the lexical properties of the denoted entities, (ii) the contextual conditions in which an entity is referred to, and (iii) the knowledge of speaker and hearer about the intended referent. Since it cannot be taken for granted that children and adults have the same means to encode particular functions, related questions are (i) what functions are associated with a particular form that is considered to be a determiner in the grammar of an adult, and (ii) which means are used by the child to determine a particular referent so that it is identifiable for her interlocutor. Gisela Berkele wrote an excellent Master’s Thesis on the acquisition of determiner functions. Her work is available in the library of the Faculty of Romance Languages at the University of Hamburg, but unfortunately it has never been published. I wish to thank her for inspiring and motivating my own work on this topic. I am grateful to Tom Roeper for extensive discussions on some of the issues presented here, and to participants of the Colloquium on the Interaction of Language Components in Bilingual Acquisition, in Hamburg in April 2005. Thanks to Katja Cantone for her disposition to reconstruct the play contexts with me, and especially to Marta and her family for making our research team welcome and assisting us in the data collection. I gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the German Science Foundation (DFG). 1 The results by Pizzuto and Caselli (1992) and Caselli et al. (1993) differ from the other studies in that Italian articles are acquired only after the age of three. However, their acquisition criterion was not 90% of suppliance in obligatory contexts, but 90% of correct suppliance in obligatory contexts, i.e. they also controlled whether the form was morphologically correct. * 1 Article variation is a means to express very fine-grained semantic and pragmatic distinctions, which adults implicitly know. I will show that children acquire these distinctions in a stepwise fashion. The functional approach to the analysis of child data is advantageous in allowing us to interpret and understand “target-deviant” uses in terms of their “functions” rather than classifying them as “ungrammatical”. In this contribution, I am attempting to modulate the dynamic process of article acquisition, which, in my view, consists in a gradual extension of the range of functions expressed by particular forms, and which results in a morphologically and syntactically explicit way of expressing object reference. Articles are free standing morphemes that are inserted before nouns to meet the syntactic requirements of a language. While article omission is a typical phenomenon in child speech, adults tend to insert articles whenever required by the target-syntax. Articles are means which allow us to be syntactically explicit with respect to the object of reference. Thus, in a language which has a highly grammaticalized article system, such as Italian, object reference is morphosyntactically very explicit. Such a language may seem to be more complex syntactically, with respect to articles, than a language which has no articles. However, this complexity in the domain of syntax is outleveled in the domain of pragmatics in the sense that identifying the intended referent in a given context is facilitated. Vice versa, languages without articles appear to be less complex on the level of syntax but more complex on the level of pragmatics. The following investigation will illustrate that the child’s acquisition path proceeds from a pragmatically determined way of referring towards a morpho-syntactically determined one. The data will be used to evaluate current syntactic models that integrate semantic aspects of article use. The plurifunctionality of articles renders the examination of naturalistic data particularly challenging. Therefore, experimental studies have been largely preferred to examine the development of article functions because they allow for the functions to be isolated. So why not resort to experimental exclusively? Because comparisons of naturalistic and experimental data reveal a discrepancy. Experimental studies seem to suggest that children are aware of the functional differences associated with article types from an early age, but it takes some years until they can express them systematically. Researchers working on naturalistic data, by contrast, noted that children use articles adult-like from the age of three, although they continue to make egocentric errors, case, gender and number errors. Thus, according to naturalistic studies, children use certain functions actively long time before experimental data would suggest. For these reasons, preference was given to the examination of naturalistic data here. The study involves a very careful analysis of the utterances and the context in which they have been produced. Why study bilingual data? One may argue that the cognitive mastery of a particular function does not guarantee its occurrence or production in the speech of children because there are additional influences on article production, positive or negative ones. I am thinking of factors such as prosody, functional load, or syncretism. In other words, if one function does not occur simultaneously in both languages of a bilingual child, this may suggest that there are other features besides the semantic ones, which render the production of articles complex and cause a delay in production. Bilingual data thus adds an interesting viewpoint to the study of articles in child speech. For the sake of simplicity, the focus of this paper will be on the acquisition of Italian, but I will draw on German data to provide the bilingual perspective. 2 The present contribution differs from most previous works on this topic in three points. First, it is based on naturalistic rather than experimental data. Second, it looks at the development of a child who grows up bilingually with Italian and German as her two languages. Third, it covers a very early stage of acquisition (between 1;6 and 3 years). 2. Functional distinctions expressed in articles In referring to articles, we tend to use the terms definite and indefinite. It is true that definite articles are largely used to refer to specific entities, while nouns accompanied by indefinite articles mostly refer to non-specific entities. However, there is no 1:1 correspondence. In fact, definite referring expressions may also refer to non-specific entities (e.g. mi piace il vino ‘I like wine’), and indefinite referring expressions to specific entities (e.g. ho visto un leone nel deserto ‘I saw a lion in the desert’). Therefore, I will use the terms definite and indefinite merely as names for the grammatical forms corresponding to English a and the. In the following I will summarize some semantic and pragmatic distinctions that are encoded on articles in German and Italian. Note that, unlike with morphological and syntactic article functions, there are no major crosslinguistic differences between the two languages. Differences mainly arise in the domain of non-specific reference, and particularly with the generic function. 2.1 The deictic and the nominative function Deictic reference is considered to involve the speaker using an indexical definite expression, often together with paralinguistic markers such as finger pointing, eye gaze, head nodding etc., e.g. Look at the/ that cat! Through the use of paralinguistic markers, identification of the referent is possible even if several entities of the same class are present. According to Karmiloff-Smith (1979), deictic reference is egocentric to the extent that the addressee has to pay attention to these markers in order to pick out the referent intended by the speaker. Acquisition studies have shown that deictic reference is almost always accompanied by additional non-linguistic markers. When uttering a deictic expression, a speaker tends to focus the object of reference rather than the addressee. Another article function that occurs very early in acquisition is the nominative, appellative or naming function; e.g. that’s a cat. Karmiloff-Smith (1979:46) characterized naming as a descriptor function rather than a determinor function, because an expression is not used to enable the addressee to pick out the intended, but to give information about the class-membership of a referent already under focus of attention by speaker and listener. 2.2 The distinction between specific- and non-specific entities According to Maratsos (1974:446), a speaker makes specific reference or an addressee understands reference to be specific, if he has in mind a particular member of the class. Non-specific reference, on the other hand, signals that no member of the class is instantiated. In adult German and Italian, the distinction between a specific member of a class and any member of a class is expressed by the variation between definite and indefinite articles (cf. (1) and (2)). 3 (1) Hai visto il gatto oggi? ‘Did you see the cat today?’ (specific reference) (2) Una volta che cambio casa, voglio avere un gatto. ‘Once I move, I want to have a cat.’ (non-specific reference) As mentioned above, not all indefinite noun phrases automatically encode non-specific reference. Some have clearly specific reference, as e.g. (3), while others may be ambiguous between both readings, as e.g. (4). (3) (4) Ieri, ho visto un gatto grigio. ‘Yesterday I saw a gay cat.’ Voglio avere un gatto. ‘I want to have a cat.’ (clearly specific) (ambiguous) Other means may help clarify the intended meaning, e.g. tense, adverbs, verb semantics, preceding or following sentences, as illustrated in (5-6) (see also Grannis 1973). (5) (6) Voglio avere un gatto. Il colore non importa. (non-specific) ‘I want to have a cat. The color doesn’t matter.’ Voglio avere un gatto. L’ho visto ieri nella finestra di un negozio. (specific) ‘I want to have a cat. I saw it in the window of a shop.’ Some authors argue that non-specific reference should be distinguished from generic reference, as in (7), because the former retains the notion of a potential instantiation implying “any non-particular member of a class” as opposed to “no concrete instantiation of a class” in the case of generics (e.g. Karmiloff-Smith 1979). (7) I gatti sono intelligenti. ‘Cats are intelligent.’ On the other hand, if we understand reference as a speech act which creates a link between a linguistic expression and real world, as suggested by Korzen (1996), the two uses become equivalent in terms of referentiality because no reference is established in either case. In this work, I will adopt Korzen’s definition of reference, but I do agree that there is a difference in meaning between non-specific reference on the one hand, as in (2) and (5), and generic reference, as in (7), on the other hand. 2.3 Identifying function, anaphoric function, and exophoric function The identifying, anaphoric, and exophoric functions are expressed by different article types, but they have something in common which distinguishes them from the uses hitherto mentioned, namely that their use requires to take into account the addressee’s knowledge and perceptability of the referent. 4 Exophoric reference may be looked upon as involving the choice of a definite referring expression when a referent is the only member of its class in the extra-linguistic setting, while an indefinite noun phrase is chosen if the referent is one of several identical ones in the given setting. The function requires consideration of the relation between objects in the extra-linguistic context, but unlike the deictic function, it does not require any additional non-linguistic markers. The following examples from a test on article-use by Schaffer and De Villiers (2000:612) illustrate the difference: (8) Emily has got two pets, a frog and a horse. She wanted to ride one of them, and so she put a saddle on it. Guess which / What was it? – The horse. (9) Three ducks and two dogs were walking across a bridge. One of the animals fell off the bridge and said “quack”. Guess which / What was it? – A duck / One of the ducks. The identifying function involves the use of an indefinite article when a specific referent is not identifiable or known for the addressee, although it is known by the speaker. In other words, the referent cannot be presupposed. If I tell you I’ve seen the gray cat yesterday, you may be puzzled because you do not know the gray cat I am talking about. That is, a new referent has to be introduced into the discourse by means of an indefinite referring expression, as in (10). (10) C’era un un piccolo anatroccolo che non sapeva nuotare. ‘There was a little duck who didn’t know how to swim.’ Once a referent has been established in discourse, it can be referred back to by a definite referring expression. Noun phrases that are used to resume mention of a previously introduced entity function as direct anaphors. For instance, the noun phrase un piccolo anatroccolo in (10) functions as antecedent for the noun phrase il piccolo anatroccolo in (11), which has an anaphoric function. (11) Il piccolo anatroccolo si sentiva giù …. ‘The little duck was sad ...’ Anaphoric reference is taken to involve exclusively linguistic procedures. It is used by the speaker to hold discourse together and implicitly to inform the addressee that he is keeping to the same theme of discourse (Karmiloff-Smith 1979:50). In naturalistic data from children younger than three years, such contexts are rare. Children do refer back to previously mentioned entities, but these entities tend to be present in the context. 3. Previous studies 3.1 The deictic and the naming function The deictic and the nominative function constitute the first semantic and pragmatic distinctions expressed in small children’s nominals. 5 Use of the indefinite article to nominate entities is very common in early discourse between child and caretaker. Similar to Warden (1976), Karmiloff-Smith (1979:65) finds that “at no age do children have difficulties in using the indefinite article in the nominative function”. In her experimental design, children had to identify objects which were hidden in bags. To elicit the naming function, one of several identical objects was put into a bag, and the child was asked ‘What is in the bag?’. Children in the youngest group (3;4-3;11) used no single definite expression, 7% of zero articles and 93% of indefinite articles (p.75). The deictic function is the first function that children associate with definite articles. Karmiloff-Smith even assumes that it is the only function mastered by three year olds, and that children are unaware of other uses of definite articles, e.g. its use to discriminate singleton objects from objects of which there are several identical ones (see 3.3). In the latter case, which would require an indefinite referring expression, they tend to overuse definites, while, at the same time, trying to point at the objects. KarmiloffSmith argues that the definite article is a sort of demonstrative for the children. Berkele (1983) casts another perspective on the acquisition of deictic reference, namely that the deictic function per se seems to be acquired before children start to use definite articles. The author examined object reference in the German-French bilingual child Caroline, noting that she produces the form [la]2 “there/the” as early as 1;10. However, [la] did not yet occur prenominally but exclusively in isolation. Clearly though, the form had a referential, deictic function because it was used to draw the interlocutor’s attention to objects. That is, children acquire the function prior to relating it to the definite article. Once article use starts, the article-noun expression becomes a new form to express an old function. In a similar vein, one may argue that children express the naming function by using bare nouns before they use indefinite noun phrases. 3.2 The distinction between specific- and non-specific entities When distinguishing between specific and non-specific entities, the article form has to be selected in accordance with inherent semantic properties of the noun, i.e. it is relevant whether the noun is count, mass, or abstract. At the same time, the article form depends on whether an entity is conceptualized as a concept (type) or as referring to a specific entity (token). This is because inherently countable objects may be construed as non-specific (e.g. I like apples), and inherently uncountable entities may be construed as specific objects (e.g. I bought this wine). Piaget (1962) believed that small children have problems to abstract away from image-based representations and to built up notions like classes and class membership. He noted that his daughter used the term ‘the slug’ for the slugs they went to see every morning along a certain road. “At 2;7;2 she cried: ‘There it is’ on seeing one, and when she saw another ten yards further on she said: ‘There’s the slug again.’” (Piaget 1962:224). Piaget suggested that his daughter neither differentiated between one and another individual member of a class, nor between an individual member and the general class they belong to. Unlike Piaget, Bickerton (1981) argued that since the specific/ nonspecific contrast is marked in all Creole languages, children must be biologically programmed to acquire it. At that time, empirical evidence for the mastery of the specific/ 2 The French article la and the adverb là are homophonous. 6 non-specific contrast in child language was not as abundant as it may have appeared to Bickerton3, but there is by now general agreement that this function is acquired early compared to other determiner functions. According to Brown’s (1973:355) naturalistic study, children control this distinction somewhere between the age of 32 months and 41 months. Maratsos (1974:448) questioned the relevance of Brown’s findings. Since they were based on naturalistic data, “[s]pecific references were largely to referents in sight of speaker and listener, non-specific reference to non-present referents”. In other words, Brown’s children may have distinguished between visible objects as opposed to non-visible objects rather than between specific and non-specific entities. However, Maratsos’ experimental studies confirmed that even the youngest children, i.e. three year olds, had extensive knowledge of specific vs. non-specific reference, which they showed by alternating between a and the (see also Maratsos 1976: 93-94). Further proof for the early mastery of the specific/ non-specific contrast was provided in subsequent naturalistic studies. Based on a longitudinal study of the bilingual German-French child Claudine, Berkele (1983) suggested that between 2;4 and 2;7 there was convincing evidence that Claudine had acquired the concept of specificity. She uttered wo’s die bäbär? ‘where’s the bear?’ when looking for a particular bear, but ein bär! ‘a bear’ in a situation in which she suddenly found a bear without expecting it. Serratrice’s (2000) Italian-English subject Carlo started to use indefinite articles to refer to non-specific referents from the age of 2;3 in Italian and from age 2;9,6 in English, i.e. at a similar age as Claudine. Based on naturalistic data from 17 monolingual Englishspeaking children, Abu-Akel and Bailey (2000) report from the age of 24 months definite and indefinite expressions were used discriminately in specific and non-specific contexts. Thus, we may expect children to show article alternation to encode the specific/ non-specific contrast from an early age, especially in looking at naturalistic data. 3.3 Article functions depending on the addressee’s knowledge of the referent 3.3.1 The exophoric function The exophoric function was studied experimentally by Karmiloff-Smith (1979). In the respective task, the child had to ask a doll to lend her one of her toys. The doll possessed various numbers of particular toys. Some of her toys were singletons, of others there were several identical ones, so that the context for exophoric reference was provided. The children were inclined to use demonstrative pronouns, even if they were told the doll could not understand what she wanted to have, and although they were placed far away from the toys to discourage the use of pointing gestures. The 3 year olds (3;0-3;11) used definite referring expressions (demonstratives and definite noun phrases) 46% of the time. However, the answers were not discriminate because the children also used definites incorrectly to refer to one of several differently colored objects (45% of the trials) and one of several identical objects (39% of the trials), whereas indefinite He cited evidence from Brown’s (1973) naturalistic data and from the experimental studies of Maratsos (1974, 1976) and Karmiloff-Smith (1979). However, Karmiloff-Smith did not manipulate specificity in any experiment, and non-specific reference was only elicited in one of the production tests conducted by Maratsos, and the children’s overall success rate in this task was not 90% (as stated by Bickerton, p. 148), but 79% (Maratsos 1976: 59) (see also Cziko 1986 for further points along these lines). 3 7 referential expressions were rarely used. Karmiloff-Smith (1979:71) concluded that “3 year olds mainly used demonstratives or definite referring expressions in a situation which called for the distinctive use of definite and indefinite exophoric reference.” 3.3.1 The identifying function The identifying function is the most extensively studied function in child language. Children have been reported to overuse the definite article, treating objects as if they were known to the hearer, although they are (i) neither present in the context, nor (ii) previously introduced linguistically, nor (iii) part of the shared world knowledge of child and addressee. Research on the identifying function can be traced back as far as to Piaget (1955), who made children tell fairy tales to each other. He noted that: “The explainer always gave us the impression of talking to himself, without bothering about the other child. Very rarely did he succeed in placing himself at the latter’s point of view” (1955:55). The incorrect use of the definite article in such contexts became known as egocentric error and has since been reported in a number of studies (e.g. Brown 1973, Warden 1976, Maratsos 1976, Emslie and Stevenson 1981, Power and Dal Martello 1986, Schaeffer 1999, Matthewson et al. 2001). Egocentricity means that the child wrongly assumes the hearer to share his/her point of view. Brown (1973:353) noted with respect to the English children Peter, Eve and Sarah, that “it seems quite likely […] that the children had not learned to “decenter,” to use Piaget’s term, from their own point of view to that of the listener when the two diverged”. Warden (1976) conducted several experiments, covering a population of 3 to 9 year olds, as well as adults. In some experiments the subjects described simple action events involving model animals to a blindfold experimenter; in other stories the subjects narrated cartoon stories to each other. His results showed that adults identified new referents prior to using the definite article, while children tended to use definite referring expressions (54% in the group of three year olds), regardless of whether the referent had been identified before. According to Warden, children under 5 years old fail to take into account the addressee’s knowledge of a referent. Emslie and Stevenson (1981) repeated Warden’s experiment with some technical improvements. They obtained a considerable improvement of the results (13% of definite expressions in the group of 3 year olds). Power and Dal Martello (1986) replicated the experiments with Italian preschool children. Egocentric errors were quite common among the 3 and 4 year olds (40%), but performance increased with age. The portion of egocentric errors fell from 40% to 18% in the five year olds. Serratrice (2000) and Berkele (1983) looked at naturalistic data in bilinguals under three years of age. Serratrice noted that in some cases in which Carlo, an ItalianEnglish bilingual, used definite articles, adults would have been inclined to use indefinite ones. She remarked that “previous contact with the book together with his adult interlocutor is sufficient evidence for Carlo to identify […] that lion as a particular one which is supposedly also familiar to his adult partner”. She assumes that the number of definite articles is largely biased by the previously shared knowledge the child has with his listener and by the deictic bias of the here and now of the situational context. Her remark pinpoints the difficulty in identifying egocentric errors in naturalistic data, where potential referents are largely present. Berkele (1983) finds the first uses of the identifying function at the age of 2;7,6. She gives examples in which Caroline introduces 8 a new animal into an acted out story saying un ein bär auch ‘and a bear also’, or in which she picks up a pair of glasses from the ground saying ich hab ein brille ‘I have a glasses.SG’, or in which she drwas the interlocutor’s attention to the drawing of a clock saying dadrauf is ein ticktack, lit.: ‘on there is a clock’. Again, the noun phrases refer to objects which are present in the context and visible to the hearer, but they clearly go beyond the function of indicating class membership. Since the child introduces or “foregrounds” a previously unnoticed object, such noun phrases may be considered as identifying, even though they refer to present objects. I sum, the majority of the elicitation tasks have confirmed that children tend to make egocentric errors, especially before the age of four. In naturalistic data, by contrast, identifying indefinite articles were found prior to the age of three, although, at the same time, children continue to make egocentric errors. 3.3.3 Anaphoric function The anaphoric function has been examined in a number of experiments together with the identifying function. Warden (1976), Emslie and Stevenson (1981) and Power and Dal Martello (1986) made children narrate simple cartoon stories based on cards. In Warden’s experiment, for example, each story comprised three sequential events, each drawn on a separate card. Each referent occurred at least twice to test whether the child would switch from indefinite to definite expressions on second mentions. The 3 and five year old children used definite referring expressions in 90% of all cases. (Note however, that the three year olds also used definites on first mentions in 54% of all cases). In the experiment by Emslie and Stevenson (1981), 3 and 4 year olds used definite referring expressions between 96 and 100% of the time, and they also used fewer definites on first mentions (between 13% and 15%). Power and Dal Martello found that that 3 and 4 year olds used definites in only 40% of all cases (see above), but there was a substantial shift from indefinite to definite articles on second mentions (85%). They suspected, however, that the shift from the indefinite to the definite article observed in some children may have been due to a “speaker-centered rule”. In other words, the children may have used the indefinite on first mentions because they were themselves unfamiliar with the referent. Therefore, in a repetition of the experiment, they had children tell the story twice to different people. As they had expected, significantly more egocentric errors were made when the children narrated the story for the second time (60% of errors). Schaffer and De Villiers (2000) conducted an experiment in which children were presented with one- to two-sentence long stories without any contextual supports; all aspects of the stories were imaged. Under the condition illustrated in (12), three year olds produced definites 96% of the time. (12) Adrienne got a pet hamster for her birthday and put it in a nice cage. It tried to escape so she quickly closed something. – What did she close? - The cage (Schaffer and De Villiers 2000: 612) The investigations suggest that children do not have particular problems in shifting from indefinite to definite articles on second mentions, but some experimental results may be biased by the fact that children tend to use definite articles already on first mentions. Thus, it is important to control whether definites and indefinites are used discriminately. 9 4. The study 4.1 Data The data presented here has been collected within the research project Bilingualism in early childhood: Comparing Italian/German and French/German under the direction of Natascha Müller. The project was part of the Collaborative Research Centre on Multilingualism in Hamburg. The following investigation is based on a longitudinal study of the bilingual German-Italian child Marta. Marta grows up in a bi-national family in Hamburg, Germany. Her mother is Italian-German bilingual and speaks to her exclusively in Italian; her father is German. Marta has a two year older brother. In the period covered by this study, the children spoke together in Italian. The child went to a German daycare, but at home the family tried to strengthen the Italian input. The father sometimes spoke Italian as well, and Marta had an Italian-speaking nanny from Albania. The girl’s linguistic development has been followed very regularly from an early age (1;6), which ensures that the onset of article use has not been missed. The part of the corpus that was analyzed for this study consists of 30 Italian and German recordings each, and contains 4479 and 2949 utterances respectively4. Marta’s linguistic development proceeds slightly faster in Italian. This is mirrored, for example, in a higher number of comprehensible words. Before age two the mean number of comprehensible utterances per recording is 33 in German and 92 in Italian. The contrast levels out with increasing age. After age 2;0, the mean is 127 in German and 194 in Italian. The higher number of utterances in Italian goes along with a faster growth of the noun and verb lexicon (see Kupisch et al. 2005). 4.2 An overview of article-use and omission Figures 1 and 2 display the distribution of article- noun sequences and bare nouns in the child’s spontaneous speech in Italian and German. Incomprehensible or partially incomprehensible article-noun sequences, mixed DPs, and target-like bare nouns have been excluded from the counts. The columns represent absolute numbers, the shaded area represents the rate of determiner omission in obligatory contexts. In both languages, the child passes through a phase in which she predominantly uses bare nouns. The distribution of bare nouns in Italian reflects a u-shaped pattern: At first, the child uses few nouns overall (which happen to be bare). Until the age of 2 years, the number of bare nouns increases with a growing overall number of nouns. From the age of 2;3, bare nouns decrease with the number of determined referential expressions increasing. There is no such clear u-shaped development in German. The overall number of nouns (bare and determined) stagnates on a fairly low level for an extended period, as the child speaks only little German. This does not produce major effects in the omission rate, though. As expected based on what we know about monolingual acquisition, article use starts later in German. The rate of omission decreases more slowly as well, but during some stages there is no statistically significant contrast between German and Italian (see 4 The number was calculated by adding up the number of utterances in each recording session. Notice that sì and no being counted once per recording. 10 Kupisch, in press). Another difference between Marta’s Italian and German noun phrases, apart from the overall number, concerns the distribution of indefinite and definite articles. While the definite article overweighs in Italian, the indefinite is used more in German. However, this discrepancy partially reflects the target-patterns (see section 5). bare nouns (%) 100 indefinite article+N 90 definite article+N 80 80 bare nouns 10 0 0 2;9,9 2;11,15 10 2;10,6 20 2;8 20 2;6,26 30 2;5,27 30 2;4,29 40 2;3,26 40 2;2,4 50 2;1 50 2;0,2 60 1;11 60 1;9,12 70 1;8,1 70 absolute number 90 1;6,26 omission in obligatory contexts (%) 100 age Figure 1: Article use and omission in Marta’s Italian bare nouns (%) 100 indefinite article+N 90 definite article+N bare nouns 80 80 0 0 2;11,29 10 2;10,20 10 2;9,22 20 2;8,26 20 2;7,7 30 2;6,10 30 2;5,12 40 2;4,16 40 2;2,26 50 2;1,21 50 2;0,16 60 1;11,21 60 1;10,2 70 1;8 70 absolute number 90 1;6,26 omission in obligatory contexts (%) 100 age Figure 2: Article use and omission in Marta’s German 11 4.3 Functional distinctions in Marta’s use of articles The functional analysis of children’s early use of articles is complicated by the fact that most noun phrases occur in isolation so that the extra-linguistic context provides the only clue on the basis of which possible functions can be reconstructed. In fact, the first article-like forms, or proto-articles5, appear while Marta is still in the one-word stage (MLU < 1.5), meaning that whenever a noun is combined with another word, the other word is likely to be an article or another kind of determiner. 4.3.1 The early stage: naming and deictic expressions Children start to refer to objects before they use articles. Their referential means are different from those of adults, though. From the first recording, Marta uses the adverb qua (in the Italian recordings) to draw her interlocutors attention to particular objects, such as toy animals or objects depicted in a book. Most of the time, the adverb is accompanied by a paralinguistic marker. In the German recording parts, too, Marta uses qua, but also the German adverb da ‘there’ and the determiner das ‘the/that’6. As noted by Lyons (1975:65-66), the deictic expression may serve various functions: (i) to draw the interlocutor’s attention to an object, (ii) to indicate which object it is that attracts her attention, and (iii) to say something about the object (its location, that she wants to have it, what it does). Concurrently, Marta uses bare nouns (e.g. pesce ‘fish’, cane ‘dog’, cavallo ‘horse’) in referring to objects. Whether she names them or makes deictic reference we do not know, as both functions may be accompanied by paralinguistic markers, such as pointing. In other words, deictic reference and naming are inseparable during this stage, and they do not involve the use of articles. The child does have a way of referring to objects, but it is different from that of adults. The period in which bare nouns, adverbs, and pronominal determiners are used to refer to objects overlaps with the first use of articles. With increasing age, determined noun phrases take over, while the use of bare nouns fades (see Figures 1 and 2). The first article, il, occurs in Italian at 1;7. From 1;8 Marta uses both indefinite and definite Italian articles. Usage in obligatory contexts increases steadily in both languages, but faster in Italian. With a few exceptions, all noun phrases before age 2;0 are isolated, i.e. occur in two-word utterances. Examples of definites in Italian include e.g. il cane (1;7) ‘the dog’, na nuno [=la luna] ‘the moon’ (1;10), la pancia ‘the belly’ (1;11), le pape [=scarpe] ‘the shoes’ (1;11); examples of indefinites are un treno ‘a train’ (1;9), un sorso [=orso] ‘a bear’ (1;10), u(n) auto ‘a car’ (1;10), un cane ‘a dog’ (1;10). In German, there are very few expressions containing articles before age 2;0 (N=4), e.g. das is eine mama ‘that’s a mummy’, noch ein, quack ‘another frog’, (hier) eine muschel ‘(here) a shell’ (all 1;11). Caution is needed when evaluating these earliest occurrences. The data suggest that the definite article is used deictically, while the indefinite one is used in the naming Some of Marta’s earliest noun phrases, especially in Italian, were preceded by proto-articles, such as [a] for la, or by monosyllabic placeholders, such as [e] or [ә]. I included them in the quantitative analysis (Figures 1 and 2) if they were clearly identified as proto-articles (and there are many unidentified phonological sequences preceding nouns). For the analysis of semantic distinctions they are mostly irrelevant because they give no clue to definiteness (German de and ei constitute exceptions). 6 Adverbs and determiners are largely selected from the language of the interlocutor. The exceptions mostly occur in the German recordings. 5 12 function, and that both are acquired early. However, it should be kept in mind that most naturalistic play contexts do not enforce one particular article type. Many contexts allow for both articles to be used, except for responses to naming-questions.7 Whenever an object is present in the communicative situation, it can either be referred to by a deictic expression (guarda il gatto! ‘look at the cat!’) to draw the interlocutor’s attention to it, or it can be named to indicate class-membership (guarda, un gatto! ‘look, a cat!’). In fact, when Marta named something with an indefinite referential expression, she often contemporaneously pointed to it, using a paralinguistic, deictic marker. Or she combined the indefinite noun phrase with another deictic expression, such as guarda ‘look’, qua ‘there’, or questo ‘this’ etc. Therefore, it is plausible to assume that there is a functional overlap of these functions in the child’s initial language. 4.3.2 The distinction between specific- and non-specific entities The data reveals that the distinction between specific- and non-specific referents is mastered shortly after the second year. Article variation between the deictic use (where the has a determinor function in the sense of Karmiloff-Smith (1979:34)) and naming (where a has no determinor but a descriptor function) is found even earlier. However, it is not clear whether the latter two functions result from the knowledge of the semantics encoded by a and the or rather from the knowledge that the expressions are used in particular communicative settings (e.g. the routinized way of identifying an object), and whether they are used discriminately (see discussion in 4.3.1). I am therefore hesitant to interpret this variation as indicative of the mastery of the functions. Univocal indications are found soon after the child’s second birthday, when nominal expressions start to be used as arguments of lexical verbs. There were numerous instances of the case in which a referent was nonspecific (for both child and listener). Subvarieties include negatives (e.g. 13-14), reference to any instance of the class (e.g. 15-19), and imagined referents (18-19). (13) (14) (15) (16 (17) (18) (19) non è una chiocciola / ‘that’s not a ...’ das nich ein baby / ‘that not a baby’ leggiamo un libro / ‘let’s read a book’ prendo un pistone / [=pistola] ‘I take a ?’ dopo metto un cerotto / ‘later I put a band-aid’ jetzt machn wir noch ein haus / ‘now we make another house’ gleich kommt eine [s]lange und esst / ‘in a moment a snake comes and eats’ (2;3) (2;6) (2;3) (2;7) (2;8) (2;11) (2;11) These occurrences are seen alongside with various categories of specific reference, in which the referent was (i) unique in the world, as in il sole ‘the sun’ (2;0), il mare ‘the sea’ (2;3), le stelle ‘the stars’ (2;5), la luna ‘the moon’ (2;6), der Weihnachtsmann ‘Santa 7 For example, questo, cosa è? ‘this, what is it?’- un gatto/ *il gatto ‘a cat/ the cat’). . 13 Claus’ (2;8), (ii) unique in the context, like la porta ‘the door’ (2;5), il letto ‘the bed’ (2;8), la finestra ‘the window’ (2;11), or (iii) made salient by looking or pointing at it, e.g. guarda la volpe! ‘look the fox!’ (2;5), guck mal den elefanten! ‘look the elephant!’ (2;10) and numerous other instances. Other uniquely referring noun phrases are kinship terms, such as lo zio ‘the uncle’, la mamma ‘mummy’, il papa ‘daddy’, il nonno ‘the grandpa’. Some referents are specific because they constitute parts of objects that have been introduced or that are immediately present and touched or focussed. Examples include il naso ‘the nose’ (2;1), col braccio fa male ‘with the arm it hurts’ (2;5), mi fa male il piede ‘my foot hurts’ (2;6,10), la coda ‘the tail’ (2;6), die nase ‘the nose’ (2;6). Other cases in which the referent is clearly specific is in alienable possessives. Here, the referent is identified anaphorically or cataphorically through the preceding or following possessor, as in le babe tis [=le scarpe di Cris] ‘Cris’ shoes’ (2;2), la sedia mia ‘my chair’ (2;6), il mio ranocchio ‘my frog’ (2;7), la casa delle tartarughe ‘the house of the turtles’ (2;10). Generic utterances with definite determiners, as illustrated in (20-24), started to be used after 2;6. They were amazingly frequent compared outcomes of previous studies (e.g. Serratrice 2000). (20) K: ce le ho anche io queste cose qua? 7 TOUCHES HER HEAD WHERE DEER HAS ANTLERS ‘do I have them too these things?’ M: solo i cervi / ‘only deer’ (2;8) (21) non si pulisce con la scopa / PICTURE: CHILDREN CLEAN A BEAR WITH A BROOM ‘one does not clean (bears) with brooms’ (2;9) (22) vivono nell’acqua le conchiglie / ‘shells live in the water’ (2;10) Ti piacciono le prugne? / ‘Do you like plums?’ (2;10) K: Chi è che mangia le noci? ‘Who is it that eats nuts?’ M: Lo scoiattolo / ‘Squirrels.’ (2;11) (23) (24) The differentiated use of definite and indefinite referential expressions in these functions reveals the child’s awareness of the fact that each choice is associated with a different conceptualization of the denoted entity, more particularly, whether it is perceived as an individual object (token) or a concept (type). The use of definite expressions with generic reference as opposed to indefinite expressions to denote any member of a class further shows that the child encodes the distinction between possible instantiations of a class as opposed to no instantiations of a class. In all of these functions, the child’s perception of and knowledge about the referent is identical to that of the interlocutor. 14 4.3.3 Identifying function, anaphoric function, and exophoric function In all article uses treated in this section, the morphological form of the article is chosen in accordance with the addressee’s knowledge and perception of the referent. There were only few situations in Marta’s German which unequivocally called for the exophoric function. One was given in a German recording at age 2;7. Several identical cars were scattered on the floor and the Marta said da ein auto ‘there a car’ pointing to one of them, and guck ein autos ‘look a cars’ pointing to another one, while correctly using the definite article whenever she referred to singletons (e.g. de kuh geht da ‘the cow goes there’ at 2;6). Such contexts did not occur in the Italian recordings. The early occurrences in Marta’s German, however, run counter to the observations by Karmiloff-Smith, according to which the exophoric function is not acquired before age 6. There is evidence for the use of the indefinite article in the identifying function as of age 2;4 in Italian and age 2;10 in German. The first context in Italian occurs while Marta pretends to cook something in a pot, which her interlocutor cannot see. On the interlocutor’s question cosa prepari? ‘what do you prepare?’ she answers un pollo ‘a chicken’. Other examples are illustrated below in (25) through (27). The referent in (26) is a ship which is not present in the context, but whose horn Marta can hear because she lives close a big river. The examples nicely illustrate the shift to the definite article on second mentions, i.e. mastery of the anaphoric use. There were fewer occurrences in German and they are restricted to constructions with avere ‘have’ (e.g. ich hab ein ganz schöns bett ‘I have a really nice bed’) or presentationals, where naming and identifying function coincide (e.g. das is ein eis ‘that’s an ice cream’ at 2;11, showing a sausage to her interlocutor). (25) K: M: K: M: M: (26) M: K: M: K: M: cos’è? / POINTS TO A TOY PLANE THAT M HAS JUST FOUND ‘what is it?’ un aeroplamo / [=aeroplano] ‘an airplane’ […] / no che bello della TUI / anch’io voglio un aeroplano / […] / ‘no how nice of the TUI / me too I want an airplane’ tieni qua / GIVES AIRPLANE TO K ‘here you are’ […] qua su, l’aeroplamo / [aeroplano] POINTS OUT DIRECTION SHE WANTS THE PLANE TO TAKE ‘down there, the airplane’ (2;4) sento una nava / [=nave] ‘I hear a ship’ oh / sì, una nave grandissima / ‘oh’ ‘yes, a very big ship’ [...] eh è là in fondo / REFERRING TO THE SHIP ‘it’s down there’ là in fondo? / ‘down there?’ sì / la mav- la nave è la in fondo / SPECIFIES REFERENT 15 ‘yes’ ‘the ship is down there’ (27) M: K: M: K: M: (2;5) qua c’è [m] un gatto / ‘there there’s a cat’ un gatto / ‘a cat’ fa miaaaaao / ‘it goes mieooow’ eh sì / ma va / SLIGHTLY IMPRESSED ‘eh yes / wow’ fa così / domme il gatto / [=dorme] MAKES A SLEEPING GESTURE ‘makes.it this / sleeps.it the cat’ (2;5) There are a number of egocentric errors. Most of them occur in Italian (12 instances); only one instance is found in German. The interlocutor’s incomprehending reaction suggests that she was not familiar with the referent indicated by the child. Note however, that in cases such as (28-29), the referent was commonly perceived by child and interlocutor, which justifies the use of a definite article, although an adult may have been more inclined to use an indefinite referring expression. (28) K: M: K: (29) K: M: K: (30) K: M: K: M: K: M: oh quest’è - / ‘oh this is –’ il tricheco / ‘the walrus’ un tricheco che carino / ‘a walrus how nice’ (2;8) e quella cos’è? / ‘and that what is it?’ la bambola / ‘the doll’ di chi è questa bambola? ‘whose is it, this doll?’ (2;8) mi fa male / COMOMPLAINING ABOUT A PAIN IN HER BACK ‘my back hurts’ sì / dopo ti metto la cremina magica / ‘yes / later I’ll put the magic cream on you’ come? / INCOMPREHENDING ‘what?’ (x) la cremina magica / REPEATS ‘the magic cream’ [...] la camina magica / [=cremina] REPEATS ‘the magic cream’ 16 K: M: K: M: K: M: K: M: K: chi è la camina magica? / ‘who is the magic ‘camina’?’ no un’altra / ‘no another’ come? / mi spieghi questa storia? / che significa? ‘what? / can you explain this story to me? / what does it mean?’ la camin- / è l’ a- è l’altra / ‘the magic - / it’s the oth- it’s the other’ l’altra chi? / ‘the other who?’ hm, ti mostro / questa / POINTS TO SOMETHING ‘I’ll show you / this’ mi mostri? / ‘you’ll show me?’ sì / SHOWS THE MAGIC CREAM TO K ‘yes’ […] hai una cremina magica tu ? / wow così non brucia? / “you have a magic cream? / wow so that it doesn’t hurt?” (2;8) Talking about one and the same referent in several turns becomes more common with increasing age, while naming objects one by one is a common procedure in the earliest phases. The increasing use of anaphoric noun phrases goes hand in hand with a change in the child’s play behavior. At first, it is rather unusual that the child plays with one and the same object for an extended period. Later, the child begins to act out stories with particular toys or toy animals, which creates more contexts for anaphoric reference. Anaphoric reference with definite referring expressions seems to be no problem at any stage of the child’s development. Reference back to previously introduced referents occur from age 2;0 in both languages. There are quite a few incoherence errors (four in German, three in Italian), i.e. cases in which Marta used the indefinite article, although the referent had been introduced before. For instance, after several references to one particular cat, she said eine katze geht schnell ‘a cat walks fast’ (2;6), intending the same cat. However, all instances could also be type references (in the sense of all cats are walking fast) and are therefore not unequivocally target-deviant. Also, there are numerous instances in which the definite article is correctly used. One could measure topic persistence and come up with a high number of correctly used definite referential expressions. The problem is, however, that all topics are things present in the setting, so that the function is again ambiguous. More particularly, the use of the definite may indicate the acquisition of the anaphoric function, but its use may also be due to common perception or deictic reference. Only in a few cases, such as (26), the latter two factors can be excluded. 5. The bilingual perspective The bilingual view on language acquisition raises the question of whether there are differences in the development of object reference in the two languages, and whether these are related (i) to more general differences in the child’s linguistic development in 17 the two languages or (ii) whether they are produced by typological differences inherent to the target-systems. In the following, I will summarize the main contrasts between the development of Marta’s noun phrases in Italian and German. They can be captured in both quantitative and qualitative terms. 5.1 Quantitative differences As regards quantity, Figures 1 and 2 have already demonstrated the lower overall production of noun phrases in German. As this holds for both bare nouns and determined nouns, it does not have any major effect on the decrease of the rate of determiner omission. The use of bare nouns does decrease faster in Italian than in German, the mean percentage after 2;5, namely 10%, is fairly low compared to monolingual German children, which may be related to a positive influence of the Romance language, as argued in Kupisch (in press). That is, the apparent delay in the onset of article and noun production does not lead to an extended bare noun stage. The share of bare nouns from the overall number of nouns is 19% in German and 14% in Italian. A second difference between Marta’s Italian and her German concerns the frequency of mixed noun phrases, i.e. noun phrases containing elements from both languages. Cantone (2004) reports a total of 86 in German but only 31 in Italian during the period before age 4.8 A related observation is the stronger disposition to imitate noun phrases (bare and determined) in German. These have not been quantified, however. The third difference is the overall distribution of article types. The share of definite articles is much higher in Italian than in German (58% as compared to 30%). This observation may have two explanations. On the one hand, it seems to mirror the patterns typical of the target-language. Kupisch (2004) reports a higher portion of definite articles than indefinite articles in adult Italian (76% and 24% respectively), as compared to German (62% and 38% respectively). In both languages, the definite article overweighs but the discrepancy between the two article-types is greater in Italian9. We may assume that children are apt to use more indefinites than adults due to the prevailing role of the naming function in early child speech. A closer look reveals that the amount of namings from the total of indefinites is also higher in German (88% as opposed to 75%). Both points together may be taken to imply that, in German, Marta prevails longer in the stage for which naming is characteristic, but for typological reasons the language contrast looks more distinctive than it actually is. 5.2 Qualitative differences As regards qualitative differences, we can observe that Marta starts to use articles later in German than in Italian. This should not be interpreted as a delay in the acquisition of German because monolingual German children are known to produce articles only by the age of two or even later. Furthermore, as mentioned above, this does not lead to an extended bare noun stage, but, on the contrary, accelerates the acquisition process, as far as usage of determiners in obligatory contexts in concerned. 8 The asymmetry may be even more striking if we consider the phase before age 3. Unfortunately, no numbers are available. 9 Possible explanations are provided in Kupisch and Koops (in prep.). 18 Table 1 indicates the first appearance of each article function in each language. Noun phrases in the identifying and generic function are observed earlier in Italian; noun phrases in the exophoric and non-specific uses appear earlier in German. However, evidence for the non-specific use in German is based on a single instance, and the nonoccurrence of the exophoric function in the Italian data may be due to the absence of contexts for it in the actual play situations. Given the scarceness of contexts for some functions, first occurrences should not be overvalued. At least, generalizations should be drawn from the more diffused functions, such as deictic reference, naming, the specificnonspecific distinction, which appear about the same age in both languages. Accordingly, there are no major differences between the two languages. Table 1: Occurrence of article functions phenomenon Italian required article deictic reference naming function distinction between specific and non-specific entities generic reference exophoric function identifying function anaphoric reference DEF INDEF DEF VS. INDEF/ ZERO DEF/ INDEF DEF/ INDEF INDEF DEF first occurrence before 2;0 before 2;0 2;3 2;8 2;4 2;0 German required article DEF INDEF DEF VS. INDEF/ ZERO DEF/ INDEF DEF/ INDEF INDEF DEF first occurrence before 2;0 before 2;0 2;1 2;7 2;10 2;0 5.3 Transfer Another question concerns the occurrence of negative transfer. As mentioned before, contrasts between the languages arise in the domain of non-specific reference. Two cases are theoretically possible: (i) overuse of articles in German contexts which do not require an article, (ii) article omission in Italian contexts which require one in Italian but not in German. For obvious reasons, the latter should only be examined from the moment that article omission has decreased below the 10% level. There is a total of three cases in German in which mass nouns are treated as if they were countable. These are cases in which the indefinite article is overused: ein trinken, lit. ‘a to.drink’ (two occurrences), and en essen, lit.: ‘a to.eat’. In both cases, a verb has been nominalized to refer to an entity. In the former case, this entity contains something to drink (a cup); in the latter case, the entity constitutes an edible object. However, none of the instances would be correct in Italian either, so that transfer could not explain them. The examples are interesting, though, because they show that the child has discovered the individualizing function of the indefinite article. Aside from these cases, mass and abstract nouns are correctly uses without an article in German, e.g. ich mach musik ‘I make music’ (2;7), un da is kaffee ‘and there’s coffee’, nein mach ich suppe ‘no make no soup’ (both 2;9). As for the definite article, it is only overused in two Italian contexts with mass nouns, e.g. questo non è la frutta ‘this is not the fruit’ (2;11), and questa è la bella musica ‘this is the nice music’ (2;10). Both nouns are uncountable in Italian. 19 There are very few article omissions in obligatory contexts in Italian after the moment that they have decreased below the 10% level for the first time. They are not limited to particular functions, but occur with first and second mentions, namings and in deictic contexts. Of interest here are the cases in non-specific contexts: adesso altro libro ‘now other book’ (2;6 and 2;7), vado a pisciata ‘I go to peepee’ (2;8), anche questo è pistola ‘this too pistol’ (2;9). Only the second case translates into a bare noun in German. In brief, article overuse occurs rarely, and it does so in both languages. The few target-deviant uses are more likely to result from problems in deciding whether particular lexical items are mass or count than from transfer. Article omission with nouns that translate into bare nouns in German is not prevailing but almost inexistent. Thus, negative transfer does not play a role in the development of Marta’s noun phrases. 5.4 Summary The findings presented in this section indicate that differences between the development of noun phrases in Marta’s German and her Italian mainly concern quantitative facets, of which the latter two mirror typological properties of the target-language: (i) (ii) (iii) (iv) (v) the overall number of bare and determined nouns the amount of mixed and imitated noun phrases the amount of namings as opposed to other functions the decrease of the rate of omission the distribution of article-types As regards quality, differences arise with respect to the following parameter, which, again, bears on contrasting properties of the target-languages. (vi) the onset of article use Differences in the order of appearance of single functions appear to be minor, and there are no apparent cases of negative transfer. Those functions that are typically acquired later appear with lower frequency in German. 6. Discussion of the results in the light of contemporary syntactic models In contemporary models in generative syntactic theory, the structure associated with noun phrases looks as in (31). The idea that noun phrases are DP, which are headed by the functional head D and take an NP as their complement goes back to Abney (1987). (31) DP 1 theD NP I sunN 20 It has recently been suggested that DP is not universally projected. Lyons (1999:323), for instances, assumes that DP only projects in languages that have definite articles: “The diachronic emergence of definite articles, then, represents the appearance of the category of definiteness in languages, and amounts to a change in syntactic structure: the creation of a DP projection.“ In recent works on noun-phrase structure we find elaborate proposals on the structure of noun phrases that go beyond the representation of functional features, such as gender, number, and case, in syntax. In Lyon’s book Definiteness, arguments are presented in favor of the view that not all articles are Ds: “While definite articles, along with other definite determiners, are associated syntactically with some Det position [...], my proposal is that cardinal, or quasi-indefinite, articles have their locus, along with numerals, in some more interior cardinality position in the noun phrase.” (Lyons 1999:105/106). Other researchers have specified the semantic function that should be associated with the head D itself, namely specificity / referentiality (e.g. De Villiers & Roeper 1995, Pérez-Leroux & Roeper 1999, Schaeffer & De Villiers 2000). In Chomsky (2000:139), we find the following quote: “In MP it is speculated that categories lacking interpretable features should be diallowed [...]. The argument carries over to other cases, among them semantically null determiners Dnull. If true D relates to referentiality/ specificity in some sense, then an indefinite nonspecific nominal phrase (a lot of people, someone that enters into scopal interactions, etc.) must be a pure NP, not a DP with a Dnull [...]. So far, however, few works in the generative framework have tried to capture the acquisition of semantic and pragmatic features in contemporary syntactic models. The exceptions are Schaeffer 1999, Schaffer and De Villiers 2000, and Matthewson et al. 2001. In all works, D is associated with specific reference, but in Schaffer & De Villiers’s proposal only specific definites are linked to DP, while specific indefinites (e.g. I saw a gray cat) are linked to NumP, a projection below DP. They argue that the two uses should be represented by different syntactic nodes because they are not acquired simultaneously. Matthewson et al. propose a range of semantic/ pragmatic distinctions that they presume to be grammaticalized in syntax. It is hypothesized that children look progressively for distinctions that expand the syntactic tree towards more specificity, where familiarity/ uniqueness is the most specific option. The most elaborate proposal, so far, has been advanced by Roeper (in press.). He proposes a fine-grained structure for noun phrases with NP and DP as principal nodes and a variety of intervening nodes between them, each with a particular reading. Given syntactic projections are conceived of as a bundle of features that in turn may represent distinct semantic formula, he assumes that “we might expect that each one would project a distinct syntactic node.” (Roeper, in press:9). As in Matthewson et al., the child is assumed to move from less specific to more specific projections (and specificity-related projections are higher up in the tree), which reflects the intuitive idea that specificity adds information. The following representation shows an adaptation of Roeper’s proposal.10 A linguistic example was added after each node, indicating the age of at the first occurrence of this function in Marta’s Italian. Roeper did not include a node for the naming function, but following Roeper’s logic, naming should be somewhere lower in the tree, and consequently acquired early, which is consistent with the acquisition data. 10 For the sake of simplicity some of the nodes were omitted. 21 (32) DP 1 D PROPER NAME 1;11: a mamma ‘the mummy’; borsa n tanja ‘bag tanja’ 1 D DEMONSTRATIVE DEICTIC 1;7: il cane ‘the dog’ 1 D DEFINITE UNIQUE 1;10: na nuna [=la luna]; 2;0: il sole 1 ‘the moon’, ‘the sun’ D PART-WHOLE 2;1: il naso ‘the nose’ 1 D DEFINITE EXPLETIVE 2;4: fare la musica 1 ‘make music’ D INDEFINITE SPECIFIC 2;4: che prepari? – un pollo 1 ‘what do you prepare? – a chicken’ NP DEF. SPECIFIC 2;3: non è una chiocciola 1 ‘it’s not a snail’ NP GENERIC 2;8: solo i cervi 1 context: only deer has horns N DEFAULT KIND 1;8: cane ‘dog’ (adapted from Roeper (in press.): 9-10) The order of appearance of the single semantic distinctions in the corpus is totally inconsistent with the idea that the semantic tree is extended from less specific to more specific functions. This remains a fact, even if we eliminate the low frequency functions for the reasons mentioned in 5.2. The evaluation of the model based on the data and vice versa raises some interesting questions. First, the functions do not appear progressively in a bottom-up fashion. This poses the question of whether syntactic nodes should be acquired in a bottom-up fashion at all or whether the child establishes the principal syntactic nodes NP and DP first and subsequently acquires the more fine-grained distinctions, such as that between generic and non-specific reference. A related issue is whether each single semantic distinction should represent a separate node or rather one of several features associated with a node. Second, the findings reported in 4.3.1 cast doubts on the assumption that all bare nouns constitute kind references, although this could possibly be argued for namings. Apparently, children can make reference to specific entities without resorting to syntactic operations, such as the merger of article and noun. This brings up the question of whether children’s early noun phrases are syntactic entities at all, or merely lexical items with referential features different from those of adults. These puzzles cannot be further explored here but the findings may initiate further elaboration of syntactic models built on the assumption that semantic properties are represented in syntax. 22 7. Conclusions The present study has shown that children the acquisition of noun phrases does not only involve a growing number of determiners in obligatory context, but also a growing number of functions that are associated with one particular article form. In the initial stage, children’s way of referring to object differs from that of adults. While adults mainly use determined noun phrase to refer to specific entities, children make specific reference by using adverbs (sometimes homophonous with articles), bare nouns or determined nouns. That is, the child’s acquisition path departs from a highly contextdependent use of referential means, then, slowly progresses towards a more morphosyntactically determined way of referring. The acquisition path resembles diachronic processes in that determination starts in the domain of specific reference (see Blazer 1979, Givón 1981, Selig 1992, Stark (in press), for the historical perspective). The functional analysis shows that even in acquisition stages in which article by children is not adult-like, it is not “erroneous”. Rather, particular functions are expressed differently that is less explicit morpho-syntactically. Although the present treatment has suggested that reference in children and adults is performed in distinct ways, the present study is in accordance with recent studies showing that children comply with adult requirements in the domain of the syntax-semantics and syntax-pragmatics interface earlier than has been previously assumed (e.g. De Cat 2004). This is because the analysis was based on very early data stage including the age before two years, and it was shown that soon after the second year, children make extensive use of articles to express semantic and pragmatic relations, similar to adults. The functional perspective also pinpoints the limits associated with input studies. The observation that frequent elements in the input are acquired early is true to some extent (see Kupisch 2004), but it does not say anything about the dynamic process in which one particular form takes on a variety of functions over time. The bilingual case sheds some more light on a functional analysis because if certain functions appear only in one of the two languages, this may be taken to mean that article used is determined by other factors besides cognitive mastery. One possibility is a general delay in the development of one language; i.e. language imbalance. Another is that certain typological characteristics of a language slow down the acquisition process. This seems to be the case for German monolingual children. In the present case, the simultaneous exposure to Italian seems to have a positive effect on the acquisition of German. Although there is a quantitative difference due to a slight imbalance towards German as the language developing more slowly, there appear to be no major qualitative differences. The data has been interpreted in the light of contemporary syntactic theories that presuppose semantically driven nodes. The data is largely inconsistent with the assumption that syntactic trees are extended from less specific towards more specific semantic features, and, provided that semantics is reflected in syntax, it provides a challenge to theories in the tradition of strong continuity. The continuity assumption may be saved by formulating additional assumptions, such as empty positions that are equipped with certain features. For instance, bare nouns may have specific reference because they are moved into an empty position that provides them with a specificity 23 feature. But so far, this solution remains speculative. And it is hard to see how it can be falsified with data from the one-word stage. References: Abney, S. 1987. The English Noun Phrase in its Sentential Aspect. PhD Dissertation, Cambridge, MA, MIT. Abu-Akel, A. and Bailey, A. L. 2000. “Acquisition and use of ‘a’ and ‘the’ in English by young children”. C. Howell, S. A. Fish and T. Keith-Lucas (eds), 45-57. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press. Antelmi, D. 1997. La Prima Grammatica Italiana. Bologna: Il Mulino. Berkele, G. 1983. Die Entwicklung des Ausdrucks von Objektreferenz am Beispiel der Determinanten. Eine empirische Untersuchung zum Spracherwerb bilingualer Kinder (Französisch/ Deutsch). MA thesis, University of Hamburg. Bickerton, D. 1981. Roots of Language. Ann Arbor, MI: Karona. Blazer, E. D. 1979. The historical development of articles in old French. PhD Dissertation. Austin: University of Texas at Austin. Bottari, P., P. Cipriani and Chilosi, A. M. 1993/94. “Protosyntactic devices in the acquisition of Italian free morphology”. Language Acquisition 3: 327–369. Brown, R. 1973. A First Language: The Early Stages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Cantone, K. 2004. Code-Switching in Bilingual Children. PhD Dissertation, University of Hamburg. Caselli, M. C., Leonard, L. B., Volterra, V. and Campagnoli, M.G. 1993. “Toward mastery of Italian morphology: a cross-sectional study”. Journal of Child Language 20: 377-393. Chierchia, G., M. T. Guasti and A. Gualmini 1999. “Nouns and articles in child grammar and the syntax/ semantics map”. Presentation at GALA 1999, Potsdam. Chomsky, N. 2000. “Minimalist inquiries: The framework”. In Step by Step. Essays on Minimalist Syntax in Honor of Howard Lasnik, H. R. Martin, D. Michaels and Juan Uriagereka (eds), 89-156. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Cziko, G. 1986. “Testing the language biogram hypothesis: A review of children’s acquisition of articles”. Language 62: 878-898. De Cat, C. 2004. “A fresh look at how young children encode new referents”. IRAL 42: 111-127. De Villiers, J. and Roeper, T. 1995. “Barriers, binding, and acquisition of the NP-DP distinction”. Language Acquisition 4: 73-104. Eisenbeiss, S. 2000. “The acquisition of the DP in German child language”. In Acquisition of Syntax. Issues in Comparative Developmental Linguistics, M. A. Friedemann and L. Rizzi (eds), 26-62. London: Longman. Emslie, H. and Stevenson, R. 1981. “Preschool children’s use of the articles in definite and indefinite referring expressions”. Journal of Child Language 8: 313-328. Givón, T. 1981. On the development of one as an indefinite marker. Folia Linguistica Historica 2. 35-53. Grannis, O. 1973. “The indefinite article in English”. Linguistische Berichte 24: 29-34. 24 Karmilloff-Smith, A. 1979. A Functional Approach to Child Language. A study of determiners and reference. Cambridge: CUP. Korzen, I. 1996. L’articolo italiano fra concetto ed entità, I-II. Etudes Romanes 36. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculum Press. Kupisch, T. 2004. The acquisition of determiners in bilingual German-Italian and German-French children. PhD Dissertation, Universität Hamburg. Kupisch, T. in press. “Acceleration in bilingual first language acquisition”. In Proceedings of Going Romance 2003, T. Geerts & H. Jacobs (eds), 183-203. Kupisch, T., K. Schmitz, N. Müller & K. Cantone. in prep. “Language dominance in bilingual children”. Ms., University of Hamburg. Kupisch, T. and C. Koops. in prep. “A comparative study of non-specific article constructions in Italian and French”. Ms., University of Hamburg/ Rice University. Lleó, C. 2001. “The interface of phonology and syntax: The emergence of the article in the early acquisition of Spanish and German”. In Approaches to Bootstrapping: Phonological, Lexical, Syntactic and Neurophysiological Aspects of Early Language Acquisition, J. Weissenborn and B. Höhle (eds), 23-44. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Lyons, C. 1999. Definiteness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lyons, J. 1975. “Deixis as the source of reference”. In Formal Semantics of Natural Language, E. Keenan (ed.), 61-83. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Maratsos, M. 1974. “Children’s use of definite and indefinite articles”. Child Development 45: 446-455. Maratsos, M. 1976. The Use of Definite and Indefinite Reference in Young Children. London: Cambridge University Press. Matthewson, L., T. Bryant and Roeper, T. 2001. “A Salish Stage in the Acquisition of English Determiners: Unfamiliar ‘Definites’”, In The Proceedings of SULA: The Semantics of Under-Represented Languages in the Americas, J.-U. Kim and A. Werle (eds), 63-72. University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics 25. Penner, Z. and Weissenborn, J. 1996. “Strong continuity, parameter setting and the trigger hierarchy: On the acquisition of the DP in Bernese Swiss German and High German”, In Generative Perspectives on Language Acquisition, H. Clahsen (ed.), 161-200. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Pérez-Leroux, A. and Roeper, T. 1999. “Scope and the structure of bare nominals: Evidence from child language”. Linguistics 37: 927-960. Piaget, J. 1955. The Language and Thought of the Child. Cleveland: World. Piaget, J. 1962. Play, Dreams, and Imitations. New York: Norton. Pizzuto, E. and Caselli, M.C. 1992. “The acquisition of Italian morphology: Implications for models of language development”. Journal of Child Language 19: 491-557. Power, R. J. D. and Dal Martello, M. F. 1986. “The use of definite and indefinite articles by Italian preschool children”. Journal of Child Language 13: 145.154. Roeper, T. to appear. “Watching noun phrases emerge. Seeking compositionality”. To appear in Acquisition Meets Semantics, V. van Geenhoven (ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Schaeffer, J. 1999. “Articles in English child language”. Presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, Los Angeles. 25 Schafer, R. J. and De Villiers, J. 2000. “Imagining articles: What a and the can tell us about the emergence of DP”. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Boston University Conference on Child Language Development, C. Howell, S. Fish and T. KeithLucas (eds), 609-620. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press. Selig, M. 1992. Die Entwicklung der Nominaldeterminanten im Spätlatein. Romanischer Sprachwandel und lateinische Schriftlichkeit. Tübingen: Narr. Serratrice, L. 2000. The Emergence of Functional Categories in Bilingual Language Acquisition. PhD Dissertation, University of Edinburgh. Stark, E. in press. “Explaining article grammaticalization in Old Italian”. Ms., Freie Universität Berlin. Warden, D. 1976. “The influence of context on children’s use of identifying expressions and references”. British Journal of Psychology 67: 101-112. 26