Senate CFA Ad Hoc Committee on Grading Report

advertisement

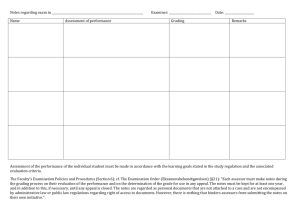

THE COLLEGE OF NEW JERSEY Faculty Senate/CFA Ad Hoc Committee on Grading in Tenure and Promotion Recommendations on Grade Distributions and Best Practices in Grading Committee Members: Lynn Bradley (Chemistry), Lisa Grega (Engineering), Rick Kamber (Philosophy and Religion), Bozena Leven (Business), Elizabeth Mackie (Art), Jacqueline Norris (Secondary Education), Felicia Jean Steele (English), Deborah Thompson (Elementary Education) Presented to Faculty Senate 12/1/2007 Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Grading and Grading Practices Presented to Faculty Senate December 2007 Executive Summary 1. Our Charge was to investigate best practices in a) grading and b) interpreting grading and to address the following concerns: a. Grading: How can grading contribute to teaching effectiveness? What are the connections between grades and student learning? How can The College help individual instructors, departments, and schools to consider philosophy and methods of effective grading? What are appropriate differences in grading among different disciplines? b. Interpreting grading: If grade distributions are to be a part of the reappointment, tenure, and promotion processes, what policies and procedures will help those involved in these processes to interpret candidates’ philosophy and methods of grading, as well as the distribution of grades in courses? How will grade distributions be used in evaluating candidates for tenure and promotion? 2. Our committee reviewed literature on grading, grade distribution, and best practices in grading, and reviewed peer institutions’ personnel policies for discussions of grade data. 3. Our review of the literature led us to an understanding that “grades, particularly final course grades as isolated artifacts, are not particularly useful …[i]f the criteria, standards, and contexts for a grade are not known to external audiences” (Walvoord and Anderson 4). 4. Moreover, despite efforts at some institutions to mandate grade distributions, particularly by high-profile neighbors in New Jersey, the committee believes that an attempt to mandate specific grade distributions in schools and departments at The College would abridge academic freedom. 5. The committee benefited immeasurably from disciplinary diversity and recognizes that different methods of assessment (for example, quantitative and qualitative, or objective and performative) may produce different grade correlates and result in different grade distributions. Most importantly, the committee agrees that our community must address our assumptions about the comparative validity of various assessment measures across The College. Revised draft as September 10, 2008 Page 2 of 8 6. The committee recommends the following: Grade distributions (and other potentially relevant grading data) may be included in tenure and promotions dossiers by candidates, but only once departments and programs have reflected upon their own grading practices and grade distributions. Departments and programs should provide materials equivalent to the disciplinary Standards for Scholarship,” so that grades are not treated as “isolated artifacts.’ If disciplinary standards for grading and grade distributions exist, grade data may be considered alongside the candidates’ dossiers, but they may not be added at a level beyond the candidate’s department. Thus, departmental personnel committees may review grade data not provided by the candidate, although they must notify the candidate and allow the candidate to interpret grade distributions within disciplinary standards created. The committee agrees that grade distributions, if included in tenure and promotions considerations, must be part of the dossier that is forwarded from departments. Promotions committees should not access materials beyond those provided by candidates and supporting departments. Committee Strategy and Framework Members of the Ad Hoc Committee on Grading represent number of different disciplines, including those that use strictly quantitative grading procedures, such as Science, Engineering, and Business, and those that use strictly performance-based measures, such as Education and Art. Faculty from the Humanities, Philosophy and English, use a combination of measures, both quantitative and qualitative. After we surveyed peer institutions’ publicly available personnel policies, we determined that few institutions like The College of New Jersey explicitly link grade distributions to personnel decisions. If they are included within those documents at institutions such as Brandeis, Lafayette, William and Mary, or Villanova, the committee found no evidence from publicly accessible policies. This absence of data provided the committee with an opportunity to begin a discussion that members believe should be afforded to disciplinary units, departments, schools, and The College as a whole: a discussion of the significance of grades, the purpose of grades, and our collective assumptions about the grading practices of our colleagues in other disciplines. Furthermore, the committee wrestled with the overall implications of grade distributions and their relevance for tenure and promotions cases. In effect, we struggled to identify the reasons why faculty would wish to include grade distributions in their dossiers at all. Revision as of September 10, 2008 Page 3 of 8 The bulk of the literature about the significance of grading in an institutional context concerns grade inflation and the relationship between grading and student evaluations. Much of the literature argues that students reward faculty for lenient grading and that higher student evaluations, important for tenure and promotion, incentivize grade inflation. Differences in employment status, for example, adjunct, tenure-track, or tenured, may affect the patterns of grading and student evaluation (Centra 2003; Sonner 2000; Wright and Palmer 2006). Some skeptics in the grade inflation debate suggest that “any increases in average grades can likely be accounted for by the demographic and institutional changes in higher education over the past two decades” (Freese, Artis, and Powell 186). The committee suggested that The College’s own demographic changes over the last fifteen years may have altered grading practices and distributions locally as well. Nonetheless, some scholarship suggests that faculty attitudes concerning grade inflation are more important than the objective evidence for grade inflation over time (Academic Leader 2004). Faculty perceptions of one another across disciplines appear to be a major issue in the admission of grade distributions to tenure and promotions cases. Valen Johnson concludes that “grading practices differ systematically between disciplines…and that [h]umanities faculty tend to grade most leniently; social sciences faculty, with the exception of economists, are approximately grade neutral; and economics, mathematics, and natural sciences faculty tend to grade most stringently” (Johnson 237). When the committee first convened, we addressed a number of stereotypes held across departments and disciplines. We discussed campus perceptions that elementary education courses, for example, lacked rigorous grading schema and inflated students’ overall grade point averages, while philosophy courses, as another example, challenged students with the sophistication of their material and the rigor of their grading. Nonetheless, materials drawn from Institutional research demonstrated that, in the Spring 2007 semester, 41.66 % of students in 100-level elementary education courses received an A or A-, while 45.88% of students in 100-level philosophy courses received the same grade. The grade distribution for B level students differed by 0.11%, with philosophy handing out the marginally higher numbers of B grades. The committee does not intend to single out these two departments for scrutiny, but to demonstrate that perceptions of grade inflation are not always supported by evidence from data. The committee agreed that grade distribution data failed to capture the range of variables that might account for the grade distribution: class standing, gender, previous course work, completion of writing courses, or access to tutoring. Faculty on the Ad Hoc committee share a consensus that discussions of grade distributions need to be embedded in a dialogue about the functions of grading and alternative methods of assessment available to faculty within programs with grade Revision as of September 10, 2008 Page 4 of 8 distributions that may deviate from the overall institutional pattern. For example, the Art department requires students to submit their portfolios of work to the faculty for jurying comparable to that artists experience in their professional careers. Such summative, qualitative, assessment is not reflected on their transcripts but is necessary for their retention in the program. The committee agreed that such professional evaluations, equivalent to the procedures that faculty members face in tenure and promotions decisions, would certainly be rigorous and reliable, although not correlated to a traditional letter-grade scale. The committee also lacked direct evidence that grade distributions measure learning in meaningful ways. For example, Virginia Anderson and Barbara Walvoord suggest that overreliance on grade distributions may “introduce dynamics that may be harmful for learning” (100). They suggest that faculty, departments, and schools should remain vigilant that the following assumptions be addressed when considering rigid grade distribution frameworks, such as those that have been introduced at Princeton University and those used in many law schools in the United States, and suggest that such grade distribution schema might reinforce such notions: 1. The notion that grades, and the learning they supposedly represent, are a limited commodity dispensed by the teacher according to a statistical formula 2. Competition among students for a limited number of high grades—competition that encourages students to keep the other person from learning, lest that other person take one of the precious and limited high grades 3. The notion that learning is a demographic characteristic that will show a statistical distribution in a sample population 4. The notion that each class is a sample population 5. The teacher’s role that focuses on awarding a limited number of grades by a formula, rather than a role that includes rewarding all learning with the grade it deserves 6. The possibility that standards for a grade will be lowered to enable a certain percentage of students to receive that grade. (100-101) Thus, the Ad Hoc committee recommends that departments, schools, and the institution as a whole engage in vigorous debate concerning the significance of grades, grading distributions, and possible alternative means of assessment (such as pass/fail) appropriate to areas best evaluated by holistic, performance-based assessment. Recommended Process for Developing Disciplinary Standards for Grading, Grading Methods, and Interpreting the Significance of Grading Throughout the process of transformation, faculty engaged in thoughtful discussion of assessment methods appropriate to their courses and programs. Every Revision as of September 10, 2008 Page 5 of 8 course proposal included a discussion of assessment artifacts, assessment philosophies, and assessment measures. Further discussion of grading, grading philosophies, and grade distributions will complement efforts begun during transformation. Grading standards for disciplines may be extracted from disciplinary syllabi, summarized, and provided to personnel and promotions committees, along with longitudinal grade distributions for departments, aggregated or delineated by course level. Institutional Research maintains such documents, and faculty may access their own grade distribution reports through SOCS. Finally, the committee endorses efforts across The College to discover authentic and reliable assessment measures of student learning that encourage faculty to refine their teaching methods over time and to respond to potential changes in student preparedness over time. Anderson and Walvoord caution faculty against using idealized grading measures, suggesting “that the meaning of a grade is socially determined. You have to teach and grade within the grading system as it is currently interpreted in the society that you and your students currently inhabit, and …have to teach and grade the students you have now, not the ones you wish you had, or the ones you had in 1975, or the ones you had when you were a TA at Berkeley” (102). Grading distributions, grading practices, and grading methods should be relevant to our current pedagogy and our current students and must be examined critically and recursively. Nevertheless, committee members recognize the relevance of grades beyond the institutional level. The committee had a rich discussion of institutional assumptions concerning external constituencies, for example, school boards, future employers, and graduate schools. We encourage The College community to acquire data that will affirm or deny our assumptions about these external constituencies and foresee a number of rich opportunities for faculty research within the new Center for Institutional Effectiveness. Conclusions The ad hoc committee on grading affirms that “When we talk about grading, we have student learning most in mind” (Anderson and Walvoord 1). Nevertheless, grade distributions do not reflect the process of grading, the communication between faculty member and student, but the final evidence of student participation in any given course recorded on a student transcript. Grade distributions may provide one piece of evidence for faculty success in communication of institutional and disciplinary goals, but we question how effectively they represent true teaching effectiveness or student learning. Grades are most meaningful when they may be correlated with other assessment measures of student learning and student success. Serious discussions of the correlates to grades has led the committee to believe that discussions of the function of grading may be less effective if framed by the grade inflation debate. We encourage faculty to reflect critically on their own teaching effectiveness and develop more sophisticated measures of Revision as of September 10, 2008 Page 6 of 8 student learning than final course grades and the resulting grade interpretation. We anticipate, nonetheless, that our discussions will offer the first step toward a fruitful and open discussion of our community’s assumptions about the significance of grades as evidence of both our effectiveness in the classroom and our student learning. The tenure and promotions processes, like grading, provide the most direct channel of communication between the institution and the individual faculty member. Despite our skepticism concerning the ultimate significance of grade distributions, we recognize that meaningful discussions of grading practices and grading distributions is most likely to happen at TCNJ if associated with tenure and promotion. Bibliography "Academic Freedom and Tenure: Benedict College (South Carolina)." Academe 91.1 (Jan. 2005): 51-54. "Correlates of College Grades." ASHE Higher Education Report 30.6 (2005): 9-14 "Faculty Perceptions, Reality of Grade Inflation Tell Two Different Stories." Academic Leader 20.11 (Nov. 2004): 3-3. "Instructors Challenge 'A for Effort' Policy." National On-Campus Report 33.1 (01 Jan. 2005): 66. "Study Reveals Faculty Attitudes About Grade Inflation." Teaching Professor 18.9 (Nov. 2004): 5-6. Centra, John A. "Will Teachers Receive Higher Student Evaluations by Giving Higher Grades and Less Course Work?." Research in Higher Education 44.5 (Oct. 2003): 495. Churchill, Louise. "Professor Goodgrade." Chronicle of Higher Education 52.25 (24 Feb. 2006): C1-C4. DeBoer, Betty V., Donna M. Anderson, and Abdulaziz M. Elfessi. "Grading Styles and Instructor Attitudes." College Teaching 55.2 (Spring 2007): 57-64. Holmes, Linda E., and Lois J. Smith. "Student Evaluations of Faculty Grading Methods." Journal of Education for Business 78.6 (July 2003): 318-323. Hoover, Eric. "Princeton Proposes Limit on the Number of A's." Chronicle of Higher Education 50.33 (23 Apr. 2004): A40-A40. James, Mark C. "The effect of grading incentive on student discourse in Peer Instruction." American Journal of Physics 74.8 (Aug. 2006): 689-691. Johnson, Valen E. Grade Inflation: A Crisis in College Education. New York:Springer, 2003. Revision as of September 10, 2008 Page 7 of 8 Kamber, Richard and Mary Biggs. “Grade Inflation: Metaphor and Reality.” Journal of Education 84 (2003), 31-37. Kreiter, Clarence D., et al. "Recommendations for Assigning Weights to Component Tests to Derive an Overall Course Grade." Teaching & Learning in Medicine 16.2 (Spring 2004): 133-138. Lammers, H. Bruce, et al. "How Hard Do I Have to Work? Student and Faculty Expectations Regarding University Work." Journal of Education for Business 80.4 (Mar. 2005): 210213. McArthur, Ronald C. "A comparison of grading patterns between full-and part-time humanities faculty: A preliminary study." Community College Review 27.3 (Winter 1999): 65. Moore, Melanie, and Richard Trahan. "Tenure Status and Grading Practices." Sociological Perspectives 41.4 (1998): 775-781. . Nasser, Fadia, and Knut A. Hagtvet. "Multilevel Analysis of the Effects of Student and Instructor/Course Characteristics on Student Ratings." Research in Higher Education 47.5 (Aug. 2006): 559-590. . Pasnak, Robert. "Research Fundamentals and the Interrelation of Emotions, Grades, and Evaluations." Teaching of Psychology 13.1 (Feb. 1986): 30. Phipps, Stephen D., Robert S. Kidd, and David A. Latif. "Relationships among student evaluations, instructor effectiveness, and academic performance." Pharmacy Education 6.4 (Dec. 2006): 237-243. Smallwood, Scott. "Faculty Group Censures Benedict College Again Over 'A for Effort' Policy." Chronicle of Higher Education 51.20 (21 Jan. 2005): A11-A11. Sonner, Brenda S. "A Is for 'Adjunct': Examining Grade Inflation in Higher Education." Journal of Education for Business 76.1 (Sep. 2000): 5. Walvoord, Barbara E. and Virginia Johnson Anderson. Effective Grading: A Tool for Learning and Assessment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1998. Wright, Robert E., and John C. Palmer. "A Comparative Analysis of Different Models Explaining the Relationship Between Instructor Ratings and Expected Student Grades." Educational Research Quarterly 30.2 (Dec. 2006): 3-18. Young, Jeffrey R. "Web Site Fights to Get Professors' Grades." Chronicle of Higher Education 53.7 (06 Oct. 2006): 26-26. Revision as of September 10, 2008 Page 8 of 8