RestrictiveCovenants

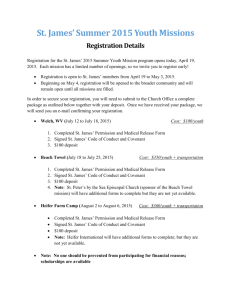

advertisement

REAL PROPERTY RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS LECTURE ON 20 JULY 2005 Note: Students should read Chapter 17 of Land Law by Peter Butt (4th Edition) and should also find and read the sections and cases referred to in the Subject Guide commencing on page 16. These notes are not a substitute for reading the text and considering the cases. Enforceability by and against successors in title Passing of burden Some definitions: Covenantor – the person having the burden of the covenant Covenantee – the person having the benefit of the covenant Positive covenant – a covenant requiring something to be done Negative covenant – a covenant preventing something being done, usually called restrictive covenants At law Between the parties to it, a covenant is enforceable under the law of contract. If either of the parties disposes of their interest in land the subject of the covenant then the new owner is not bound by the terms of the covenant. If the covenant can be said to "run with the land" then all future owners are bound by the terms of the covenant. The common law rule is that covenants do not run with the land. In Austerberry v Oldham Corporation (1885) 29 Ch D 750 (1) the English Court of appeal decided that a covenant requiring the expenditure of money on a road was not enforceable by one of the owners fronting the road against the Oldham Corporation which had acquired the road. The covenant required the predecessor in title to the Oldham Corporation to upkeep the road at its expense. After acquiring the road, the Corporation attempted to recover rates from the adjoining owners. The Court held that although both the Corporation and Austerberry acquired their respective interests in the road and the adjoining lands with notice, that the covenant did not "run with the land". Section 70A Conveyancing Act 1919 70A (1) provides:1 of 14 “A covenant relating to any land of a covenantor or capable of being bound by the covenantor by covenant shall, unless a contrary intention is expressed, be deemed to be made by the covenantor on behalf of himself or herself and the covenantor’s successors in title . . . and . . . shall have effect as if such successors . . . were expressed.” Section 70A of the Conveyancing Act appears to operate to make a covenant run with the land by deeming that successors are bound even if not expressed to be so bound by the document. Butt says that the accepted view is that s 70A does not change the common law position, and that a covenant cannot bind successors in title even if it expresses that it does so. This being the case, s 70A does not improve the position. Section 70A (according to Butt) merely affirms that the covenantor remains liable to the covenantee in contract even after disposing of the interest in land. Various devices have been used to try and circumvent the problem. There is a description of these in Butt at [1706] – [1712]. In Halsall v Brizell [1957] Ch 169 (2) the benefit/burden doctrine was considered. In that case, a subdivision was effected in 1851 incorporating covenants contained in a deed. One of these required the several owners of the lots to contribute to the cost of upkeep of roads etc. in the following terms:“. . . ‘Seventhly. That each and every of them the said persons parties to these presents and his respective heirs executors administrators and assigns shall and will from time to time contribute and pay a due and just proportion in respect of the plot . . . of land in the said plan [drawn upon the deed] marked with his name . . . and of the dwelling. house on each such plot erected or to be erected in common with the owners of the several other plots of land described in the said plan of all costs charges and expenses’ in maintaining and keeping in good repair the aforesaid roads, sewers, promenade and sea wall ‘for the common use convenience and advantage of the owners for the time being of the several plots of land described in the same plan and of the dwellinghouses erected or to be erected thereon . . .’ ” In 1950, the AGM of proprietors decided to levy the charges on the lot the subject of the case by increasing the amount because the house had been divided into flats. The court held that prima facie the covenant was unenforceable. “(1) that prima facie the covenants contained in the deed were unenforceable in that (a) a positive covenant in the terms of the seventh covenant did not run with the land; (b) the particular provisions in respect of payment of calls plainly infringed the rule against perpetuities;” “(2) the defendants, who could not rely on prescription or a way of necessity, were not entitled to take advantage (as they desired) of the 2 of 14 trusts concerning the user of the roads contained in the deed and the other benefits created by it without undertaking the obligations thereunder, viz., the payment of calls, and that on that principle they were bound by its terms.” The problem with this device is that it only works where an owner needs the benefit of the thing that is to be paid for. In Halsall, the owner needed the benefit of the roads etc and accordingly had to pay for the use of these facilities. Butt refers to this as the “conditional benefits” principle [1710] where there needs to be a choice for successors in title to decide whether they want the benefit of what is offered in exchange for the burden, or payment of money, required by the document. In Rufa v Cross [1981] Qd R 365 (3) a party wall was constructed on a common boundary between properties. Subsequently, the owners agreed by deed to grant easements over the site of the wall and included covenants that either owner by notice to the other could extend the wall and that if the other owner later decided to use the extended portion of the wall that the second owner would pay for part of the cost of construction. The District Court judge found that the right to extend the existing wall and the right to use that extended portion were rights capable of forming the subject matter of a grant of easement and that where the appellants took the benefit of the deed, they were bound by the conditions in it. This was so, despite their not being parties to the deed. The Queensland Full Court dismissed an appeal from the District Court. In their judgments the Court said:D. M. Campbell, J.: “It was argued for the appellants that a covenant to pay does not run with the land, and this is so in equity with the type of servitude known as the restrictive covenant. But here the type of servitude is an easement. Once an easement is properly created, the benefit of it will pass with the dominant tenement and the burden will pass with the servient tenement to the successive owners of the two tenements: . . .” “The right to extend the existing party wall is clearly a right capable of forming the subject matter of grants of easements. In my opinion, the right to use the extended portion of the wall provided the neighbour seeking to use it contributes half its value is a right of the same character. Part of the normal enjoyment of the properties is being able to have the use of the party wall. Whether the positive covenant to repair runs with the land is another question. In Liverpool City Council v. Irwin [1971] A.C. 239, at p. 259, Lord Cross referred to – “the general principle that the law does not impose on a servient owner any liability to keep the servient property in repair for the benefit of the owner of an easement.” Apart from express contract this is the principle. The question whether the covenant to keep the party wall in repair is one that the successors in title of the original covenantee could enforce does not fall for decision in this case and it is better that it be left until it does arise. I agree in the main with the view taken by the learned District Court judge.” 3 of 14 Kneipp J.: “It is laid down in Coke on Littleton, 230b, that “a man who takes the benefit of a deed is bound by a condition contained in it though he does not execute it”: per Cozens-Hardy M.R., arguendo, in Elliston v. Reacher [1908] 2 Ch. 665 at 669. It is sometimes put in Latin: qui sentit commodum sentire debet et onus. Examples of its application are Aspden v. Seddon (1 Ex. D. 496). Westhoughton U.D.C. v. River Douglas Catchment Board [1919] 1 Ch. 159, 171, and Halsall v. Brizell [1957] Ch. 169. It seems that the easements in the present case were executed under seal, but in any event they had the effect of a deed on registration: Real Property Act of 1861, s. 35. In the present case, the building of the defendants in at least one respect encroaches on to that part of the wall which stands above the plaintiff’s land. If it is assumed, as I think it should be, that this is justified by reference to the relevant easement, then I think that they should bear the obligation imposed by that instrument to pay half the cost of the wall. I think, therefore that the appeal should be dismissed with costs.” Similarly, in Frater v Finlay (1968) 91 WN (NSW) 730 (4) the Court held that a successor in title was able to recover the cost of repairs under a covenant contained in a grant of easement where the grant was coupled with the promise to pay for repairs in return for the grant. The defendant contended that the covenant to pay for half of the cost of repairs was a personal covenant between the predecessors in title and did not run with the land. In his judgment, Newton D.C.J. referred to a decision of the Supreme Court of New Zealand (Cameron v. Dalgety [1920] N.Z.L.R. 155.) and to the decision in that case by Herdman J. After discussing some other references Newton D.C.J. said in his judgment:“It seems to me, with great respect to Herdman J., that his reasoning is sound, and if the grantor of an easement can bind himself and his assigns to repair by the grant then, a fortiori, the owner of the dominant tenement can bind himself and his assigns to repair or to contribute to the cost of repairs if the repairs are carried out by the owner of the servient tenement. I am somewhat fortified in this view by the decisions in Re Ellenborough Park [1956] 1 Ch. 131 (Danckwerts J., as he then was, and the Court of Appeal). After discussing the facts and circumstances in Re Ellenborough Park Newton D.C.J. went on to say:“It also seems clear to me that the obligation of the owner of the dominant tenement to pay half the cost of keeping the well and pipes and tanks and equipment in good order and condition cannot, in itself, amount to an easement independent and separate from the easement to receive water. Viewed on its own, the obligation to contribute could not comply with the second essential of an easement, namely that it must accommodate the dominant tenement. This means that what is required is that the right “accommodates and serves the dominant tenement and is reasonably necessary for the enjoyment of that tenement; for if it has no necessary connection therewith, for although 4 of 14 it confers and advantage upon the owner and renders his ownership of the land more valuable, it is not an easement at all but a mere contractual right personal to and enforceable between the two contracting parties”.” “In my opinion the obligation of the grantee of the easement to contribute half the cost of repairs formed part of the easement and therefore binds the successors in title, and therefore the plaintiff is entitled to recover one half of such moneys as he is able to prove were expended by him within the terms of the grants.” The Court held that the covenant was part of the easement and did bind successors in title. In equity As the common law was intransigent in its approach to the problem, equity was left to try and temper this. The equitable doctrine relating to negative or restrictive covenants was settled in the case of Tulk v Moxhay (1848) 41 ER 1143 (5). In Tulk, land was sold by Tulk to a purchaser for use by the purchaser but containing a covenant that, amongst other things, the land could not be built upon. Moxhay subsequently purchased the land by conveyance that contained no covenants but he did admit knowledge of the original covenant. An injunction was granted to restrain Moxhay from building on the land and an appeal dismissed. The Lord Chancellor said that the question of whether equity would intervene was independent of whether the covenant was said to run with the land. It was not reasonable for a person purchasing with notice to be in a better position than the person from whom he purchased. Lord Cottenham, L.C. explained it this way: “It is now contended, not that the vendee could violate that contract, but that he might sell the piece of land, and that the purchaser from him may violate it without this court having any power to interfere. It that were so, it would be impossible for an owner of land to sell part of it without incurring the risk of rendering what he retains worthless. It is said that, the covenant being one which does not run with the land, this court cannot enforce it, but the question is not whether the covenant runs with the land, but whether a party shall be permitted to use the land in a manner inconsistent with the contract entered into by his vendor, with notice of which he purchased..” . . . “That the question does not depend upon whether the covenant runs with the land is evident from this, that, if there was a mere agreement and no covenant, this court would enforce it against a party purchasing with notice of it, for if an equity is attached to property by the owner, no one purchasing with notice of that equity can stand in a different situation from that of the party from whom he purchased.” Requirements Negative 5 of 14 Equity will only enforce negative covenants. Butt sets out the logic at [1728] – [1730]. Owner buys land subject to a covenant that deprives the purchaser of rights to do certain things. If equity refused to assist a person having the benefit of the covenant against a purchaser then the purchaser would have acquired rights that the vendor did not have. The question of whether a covenant is negative or not is one of substance. Generally, if a covenant requires the expenditure of money then it is a positive covenant. In Tulk v Moxhay the covenant was to keep the park "in an open state, uncovered with buildings". Benefit covenantee's land The covenant must benefit the land of the covenantee at the time the covenant is created. In Forestview Nominees Pty Limited v Perpetual Trustees (1998) NSW ConvR ¶55-846 the High Court considered the terms of a restrictive covenant expressed as follows: “Covenant binds successors in title The covenants made in clause 1 by the Transferor (‘the Restrictive Covenant’) are made for itself and its successors in title as the registered proprietor or proprietors of the Burdened Land or any part or parts of it with the intent that the Restrictive Covenant will enure only for the benefit of the Transferee and its successors in title as the registered proprietor or proprietors of the Benefited Land or any part or parts of it. Without limiting the generality of this clause 2, the Restrictive Covenant will not enure for the benefit of any tenant for the time being of the Benefited Land or any part or parts of it.” “For the purpose of section 129B of the Transfer of Land Act 1893, the registered proprietor of the Benefited Land for the time being and the registered proprietor of the Burdened Land for the time being covenant with each other that the Restrictive Covenant is entered into for the benefit of the registered proprietor of the Benefited Land and its successors in title and is not entered into for the benefit of any other person. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, the Restrictive Covenant is not entered into for the benefit of any tenant for the time being of the Benefited Land.” Forestview and Silkchime, the proprietors of the burdened land, argued that the wording of the restrictive covenant was fatally flawed because of the wording that it “will not enure for the benefit of any tenant for the time being of the benefited land or any part or parts of it”. They argued that because it did not benefit any tenant then it did not touch and concern the land. 6 of 14 The Hight Court then considered the doctrine set out in Tulk v. Moxhay and the application of this doctrine to later cases. The judges referred to an article entitled “Specific Performance For and Against Strangers to the Contract”, (1904) 17 Harvard Law Review 174 at 183 by Ames and said: “It follows that the basis upon which equity deals with the attachment to the benefited land and the transmission of the benefit of restrictive covenants is that which was identified by Ames nearly a century ago. He said that the right of third persons to the benefit of restrictive covenants is the result of the just and simple principle [67]: “that equity will compel the promisor to perform his agreement according to its tenor. If the restrictive agreement, fairly interpreted, was intended for the sole benefit of the promisee, only he can enforce it. If on the other hand it was intended for the benefit of the occupant or occupants of adjoining lands, then such occupant or occupants may compel its specific performance.” The Court rejected the argument that the covenant did not touch and concern the land because the tenants of the proprietor of the benefited land could not enforce the covenant (because of the terms of the restriction) and agreed with the primary judge “that the value of the benefited land was enhanced by the restrictive covenant”. The Court found that the restrictive covenant was valid and did touch and concern the benefited land. Intention At the time of creation, there must have been an intention that the burden of the covenant should run with the land of the covenantor so that the successors in title were bound. The use of the words "heirs and assigns" was traditionally used. Section 70A of the Conveyancing Act might not change the common law that a covenant does not run with the land but does assist in an equitable argument. As the section says that a covenant can be deemed to be entered into on behalf of the covenantor and his successors in title, then the necessary intention can be argued. That is, that in equity the successors are bound even if they are not bound at law. Passing of benefit At common law the benefit of the covenant runs with the land benefited allowing the owner of the benefited land to enforce the covenant against the covenantor, but not the covenantor's successors. The accepted test is that the covenant must "touch and concern" the covenantee's land. 7 of 14 In Rogers v Hosegood [1900] 2Ch 388, the English Court of Appeal considered whether a covenant ran with the land in circumstances where the purchaser was not aware of the covenants given by the purchaser of other lots. A brief synopsis of the facts is as follows: Land conveyed by owners and mortgagees with a covenant in favour of the owners that the land would not be used for anything other than a single dwelling house. A second lot adjoining the first was conveyed on the same basis. Subsequent purchaser bought other nearby land separated by one lot from the first purchaser’s land and entered into a covenant that he should not build more than 2 dwelling houses on the land. Second purchaser unaware of the covenants in the first 2 conveyances. The intervening land sold to the first purchaser without any covenant. Covenants over the first two lots released by the vendors. Rogers bought 2 other lots nearby. Hosegood purchased the 3 lots sold to the first purchaser. Action to restrain the construction of a block of flats on the first lot. Held that: The assigns of the second plot could enforce the covenant against the assigns of the first plot; The erection of a large building to be occupied as residential flats would be a breach of the covenant; Although the mortgagors had released the covenant so far as the number of houses was concerned, any building must be used for a private residence only and the proposed building would be a breach of this covenant as well. The covenant will not be enforced where the land alleging the benefit is so large that it cannot reasonably benefit from the covenant. In In re Ballard's Conveyance [1937] Ch 473 (7) the court held that where a covenant purporting to "touch and concern" land does not "touch and concern" the whole of it, then the court will not enforce the covenant and has no power to sever the part of the land which is affected and leave the remainder of the land free from the covenant. In his judgment His Honour Clauson J. said: 8 of 14 “I accordingly hold that the land for the benefit of which the covenant was taken was the land (about 1700 acres) now vested in Childwick Bury Stud, Ld., by conveyance from Mr. Joel, and that the fact that they claim by virtue of a purchase from Mrs. Ballard would not affect their title to sue.” . . . “It appears to me quite obvious that while a breach of the stipulations might possibly affect a portion of that area in the vicinity of the applicant’s land, far the largest part of this area of 1700 acres could not possibly be affected by any breach of any of the stipulations.” . . . “The result seems to me to be that I am bound to hold that, while the covenant may concern or touch some comparatively small portion of the land to which it has been sought to annex it, it fails to concern or touch far the largest part of the land. I asked in vain for any authority which would justify me in severing the covenant and treating it as annexed to or running with such part of the land as is touched by or concerned with it, though as regards the remainder of the land, namely, such part as is not touched by or concerned with the covenant, the covenant is not and cannot be annexed to it and accordingly does not and cannot run with it.” In contrast to this decision, in Marquess of Zetland v Driver [1939] 1 Ch 1 (8) the English Court of Appeal upheld an appeal from a decision of a judge in the Chancery Division and found that that a covenant "for the benefit and protection of such part or parts of the settled land as should etc". The reason for the finding in this case was that the covenant was expressed to be for parts of the remaining land and not, as in Ballard’s case, for the whole land. In Ellison v O'Neill (19680 WN (NSW) (pt1) 213 (9) the New South Wales considered the application of the rule that the benefit must touch and concern the land benefited in circumstances where the dominant and servient tenements were both subdivided. The court held that on their true construction, the covenants were for the benefit of the whole of the dominant tenement and not for such lots into which it might be subdivided. The question of intention is also relevant. It is necessary to look at the true intention of the words used. It is only possible to look at the words found in the document. In Kerridge v. Foley (1964) 82 WN (NSW) (pt 1) 293, the court was asked to consider the effect of restrictive covenants purported to be created by conveyances of old system land from the Australian Agricultural Company. The conveyance of lot 53 had endorsed on it a plan showing lots 52, 53, 54 and 61. The AA Company subsequently sold lot 52 with identical covenants and a plan showing lots 51, 52, 53 and 62. The covenants purported to provide that “only one house shall be erected upon each40 feet of frontage . . .”. 9 of 14 His Honour Judge Jacobs J. found that: “It therefore cannot be said that the instruments of conveyance clearly indicated the land to which the benefit of the restriction was appurtenant because it included land, namely lot 54, to which the benefit of the restriction was not so appurtenant; that being so, s. 88 of the Conveyancing Act provides that a restriction shall not be enforceable against the defendants who are persons interested in the land claimed to be subject to the restriction and not parties to its creation. It is probable that the same result follows at common law. See Re Ballard’s Conveyance (1).” His Honour also found that as both lots 52 and 53 had been in common ownership between 1953 and 1958 that the covenant had merged as: “a person cannot be regarded subject to the burden of a covenant of which he alone has the benefit.” Dealing with the question of whether the covenant prevented construction of more than one dwelling on the block of land expressed to be 49 feet wide in contravention of a covenant not to build more than one house upon each 40 feet of frontage, His Honour could not find “a certain meaning” to this covenant. Section 70(1) of the Conveyancing Act now imputes an intention that successors are benefited. The section applies to all covenants created after the section came into effect in1930. For covenants coming into effect prior to that date the earlier section 70(1) is applicable and couched in different terms. If you are called upon to examine the effect of a covenant then it is relevant to make sure that you look at the proper section. Where the benefit of a covenant is found to attach to land then there is nothing further to be done. The benefit is "annexed" to the land. Common law requires nothing more. As the benefit of a covenant is a legal chose in action, it can be assigned under section 12 of the Conveyancing Act. Statutory requirements Old system land Restrictive covenants are equitable interests and do not therefore require creation by deed. They do require writing in the absence of part performance. (Sections 23C and 23E Conveyancing Act.) Torrens title land Normally created by transfer in an approved form. If not, then created by deed annexed to a request to note the effect of the deed in the register. The Conveyancing Act 10 of 14 Section 88 88(1) sets out the four elements of a document to formally create an easement or restrictive covenant. 88(3) provides that the section applies to land under the Real Property Act. Section 88B The most common method of creating either an easement or a restrictive covenant is by registration of a plan of subdivision and the use of an instrument under section 88B. The form used sets out all the information required by section 88 and the certificates of title that issue after registration all have the appropriate notifications on them as to both the benefit and burden of any easements or restrictive covenants. In Kerridge v Foley (1964) 82 WN (NSW) (pt 1) 293 (10) land was conveyed subject to a covenant concerning the number of dwellings on each 40 feet of frontage and as to the use of the premises. The defendants intended to convert the house into two dwellings and the plaintiff objected. The court held that the covenant was not enforceable as it did not meet the requirements of section 88. The conveyance described the land to which the benefit was appurtenant as "the whole of the land shown in the said plan". The plan was endorsed on the conveyance and showed lots 52, 53, 54, and 61. The land being sold was lot 53. Jacobs J found that the inclusion of lot 54 in the plan was not correct as lot 54 had been sold previously to a named purchaser and was not owned by the original vendor, the A A Co, at the time of the first sale of lot 53. Lot 54 was not subject to the restriction as it had been sold previously and could not be the subject of a restriction created after its sale and purporting to affect it. Section 88E This section allows "prescribed authorities" to impose restrictions and/or public positive covenants on land and enforce them against the owner for the time being of the affected land, without the need for the covenant to benefit any other land. An example of this is a covenant that requires a landowner to keep part of his or her land clear of undergrowth for the prevention of bush fire. Public positive covenants are becoming more common. Extinguishment of Covenants Section 28(2) Environmental Planning and Assessment Act Section 28(2) allows for development of land to proceed contrary to the provisions in a restrictive covenant where an approval is granted for 11 of 14 development pursuant to a planning instrument that contains a clause allowing for the suspension of covenants. It is pointed out by Butt [1792] that the covenant is “nullified” by the operation of s. 28 (2) and a development consent. This issue was considered by the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Coshott v. Ludwig (1997) NSW ConV R 55-810. Express release For land under old system, a restriction can be released by deed registered in the Land Titles Office, and for land under Torrens title, by deed and request to the Registrar General. In Jones v Sherwood Hills Pty Ltd (1975) 52 ALJ 223 (note) (14) the Court held that it was possible to give the right to vary modify etc a restriction to a person or company with no interest in the land. From a practical point of view, this makes it difficult to know how to advise clients when purchasing property. Operation of law Where land the subject of restrictive covenants comes into the same ownership the covenants are extinguished. See Kerridge v Foley. There are three exceptions: 1. where the covenants are over land under the Torrens system. Because of section 88(3) a covenant recorded on the register is an interest under section 42 of the Real Property Act and has the same protection as other interests. 2. where the covenant is created by the registration of a plan and section 88B instrument. (88B (3) (c) (iii) 3. where a scheme of development exists. In this case, when lots come into common ownership the operation of the covenant, as between the owner of the lots, is suspended. The covenants are still enforceable by any other person having the benefit of the covenant. (We have not dealt with building schemes.) In Post Investments v Wilson (1990) 26 NSWLR 598 (15) the court held that the common law doctrine of extinguishment of interests in land by merger of the title does not apply to land registered under the Real Property Act. His Honour Powell J. also considered an application under s. 89 of the Conveyancing Act and made the following observations: “Although, as will be obvious from what I have recorded above, it is clear that the character of the general neighbourhood in which the defendants’ land is situated is in the process of change, I am unable to accept that the facts, first, that the area is now zoned so as to permit medium density housing, and, secondly, that advantage has been taken of the fact to build some town-houses and home units in Parriwi Road, 12 of 14 are – whether separately or in conjunction – sufficient to conclude, either, that the restrictions on any of the three properties are obsolete, or, that their continued existence will impede the reasonable use of any of the properties without securing practical benefit to anyone. Whether one regards the covenants as intended merely to preserve the view from the defendants’ home, or as intended, as well, to preserve a substantial degree of privacy for the defendants’ property by prohibiting the erection of substantial structures close to the eastern boundary of the defendants’ land and in a position in which they would overlook the defendants’ land, each of those objects can still be – and, indeed, is presently being – achieved: see Re Truman, Hanbury Buxton and Co Ltd’s Application; Heaton v Loblay; Re Mason and the Conveyancing Act; Re Robinson. As I have earlier recorded – notwithstanding the fact that the alterations made to No 40 Parriwi Road in 1984 have deprived the defendants’ home of the former view to the north towards Clontarf – the view, even from the ground floor of the defendants’ home, to the northeast and to the east, remains, in a word, spectacular, while, notwithstanding the recent erection of town-houses or units on No 34 Parriwi Road, the rear garden area of the defendants’ land remains a very private, tranquil and aesthetically pleasing place. Nor can it possibly be said that there can be no possible reasonable user of the three properties unless the restrictions be extinguished or modified: Heaton v Loblay; Re Callanan and the Conveyancing Act; Guth v Robinson; Re Alexandra. Not only do the houses erected on each side of the three properties – although elderly – appear to be in substantially good order, but, as best as I could judge it, there still remain in Parriwi Road – both to the north of the three properties on the western side of Parriwi Road, and to both north and south on the eastern side of Parriwi Road – a significant number of conventional homes.” Order of the Court Section 89 of the Conveyancing Act gives to the Court power to make various orders for the variation, modification or extinguishment of covenants. The intention of the section is not to allow a person to benefit from being able to extend the use of land contrary to a covenant because it suits the person seeking the modification or removal to do so. The court will look carefully at the section and the elements contained in it before making a decision. See section 89. Butt deals with each of the parts of section 89 in [1783] – [1787]. In Re Truman, Hanbury, Buxton and Co Ltd's Application [1956] QB 261 (16) the English Court found that an application to declare a restrictive covenant to be obsolete could not be granted as the character of the area had not changed sufficiently for the Court to be satisfied. The Court held 13 of 14 that a time might come when such a change could have occurred but that it had not yet. The Court agreed that the removal of the covenant would injure persons admitted to have the benefit of the covenant. In these circumstances, the Court held that the covenant could not be held to be obsolete. In Re Application of Poltava Pty Limited [1982] NSWLR 161 (17) Master Cohen considered the effect of the decisions in Elliston v Reacher and Kerridge v Foley and came to the conclusion that a building scheme existed. This gave seven additional parties the right to object to the application. Master Cohen found that it was up to the persons claiming a building scheme to show that it existed. Master Cohen then examined the covenants and concluded that the construction of a further house would be injurious to adjoining owners. This being so, it was not possible to say that the covenant was obsolete. Cohen referred to Mason. In Re Mason and the Conveyancing Act (1960) 78 WN (NSW) 925 (18) Mr Justice Jacobs held that the purpose of section 89 is to allow removal or modification of covenants that have no real benefit. In this case, the covenant was not obsolete because it prevented the construction of home units that would have blocked, substantially or wholly, the view from existing premises. Jacobs also discussed the question of "substantial injury". He concludes that this means: "I consider in its context it does not mean large or considerable but it means an injury which has present substance; that is to say not a theoretical injury but something which is real and which has a present substance." Jacobs dismissed the application. Real Property Act Part 8A Under the provisions commending at s 81 the Registrar is authorised to remove some restrictive covenants as set out in those sections. 14 of 14