Problems and Prospects for Clusters in Theory and Practice

Problems and Prospects for Clusters in Theory and Practice

Philip Cooke, Centre for Advanced Studies, Cardiff University

Introduction

We have seen that since Marshall, observers have spoken of certain agglomerations of specialised economic activity as, first ‘industrial districts’ and more recently ‘clusters.’ When they do this they are mainly speaking of a concrete phenomenon rather than an artifice.

Usually they mean many firms in more or less one place, the firms competing but having at least preferential relations with some. These relations may range from ‘preferred supplier’ contractual status at one end of the spectrum of economic interaction, to high-trust, non-

1 contractual collaboration, exchanging of favours and non-monetary transactions at the other.

So a question that is of undoubted and abiding interest to economic geographers and others is why, in a world largely characterised by utilitarian, unsentimental buying and selling, do clusters exist? They ought to have disappeared with the medieval guilds, the source that

Marshall, in effect, gave as the ultimate origin of industrial districts. Certainly, they ought to have been replaced by the modern business corporation with its advantages in resource and administrative capabilities that have exercised generations of industrial economists from

Young (1928) to Coase (1937), Penrose (1959), Richardson (1972) and the modern dynamic capabilities authors like Teece & Pisano (1994), Winter (2000) and Zollo & Winter (2002).

But of course, the smaller firms that often comprise industrial districts are nowadays far from being effaced from the economic landscape. Indeed we are in an era when ‘entrepreneurship’ is used as a policy injunction for practically everyone from the unemployed to star scientists in universities. Moreover, such is the perceived success of many small and medium-sized firms interacting profitably in confined geographical locations that many seek to emulate them. The likes of Como, Italy where the world’s leading silk design capabilities are found, or

Carpi, in the same country, from where similarly high-quality knitwear originates, and Salling in Denmark, with its 43 woodworking and furniture factories at the centre of the high-quality

Danish furniture industry have become policy role-models. Furthermore, while concentrations of such firms are competitive in design-intensive, quality markets that large corporates find impossible to break into, such expertise is not confined to high-end production only. Thus,

Parma produces much of Italy’s mass-market cheese, as well as supermarket prosciutto ,

Montebelluna’s 500 firms produce 80% of the world’s motorcycle boots, 75% of its ski boots and 50% of its track shoes, while Belluno produces a two-thirds of the world’s spectacles, its

turnover accounting for 85 % of Italian production with more than 70 % exported. Thus, many of these significant market shares are not confined to luxury but to niche production.

2

Hence, for such proximate production formations of specialised smaller firms to be thriving, there must be problems with the conventional economic perspective that once posited their demise. Therein lies the answer to the question why industrial districts and clusters exist: the inevitability of economic dominance by large scale production and ‘trading with strangers’ were mistaken assumptions. It is nowadays becoming clearer by the hour that the military or

‘M-form’ firm is by no means universally the optimal organisational mode for industrial production. In particular, it has reached its limits regarding innovation potential derived from in-house control of R&D, a historic core competence, as Chesbrough’s (2003) analysis of innovation outsourcing has convincingly shown. Sharing the missing spatial insight of most industrial economists, he nevertheless shows how private R&D investment in the US switched by thirty percentage points from large to small firms 1981-1999. Overwhelmingly such firms, especially in biotechnology and ICT, two of the most research intensive fields, operate from cluster bases like Silicon Valley and Greater Boston. Moreover the theory of economic relationships that stressed utilitarian anonymity in production and consumption has also proved to be correct only in special circumstances such as ‘spot markets’. But more general market relations are now understood to be based on varying, but often significant magnitudes of ‘social capital.’

Markets and Social Capital

Social capital is the concept of reciprocal, trust-based exchange of resources based on reputation and traditional or communally established norms (Jacobs, 1961; Coleman, 1988).

It involves at one extreme, for example, exchange of favours, and at the other, preferential economic practices among firms which are pecuniary rather than simply forms of ‘untraded interdependency’ (Dosi, 1988). This previous statement is an important point as many interpretations of social capital stress the collectively-minded, barter-like interactions neighbours, families, or communities might engage in. It is then a short, albeit mistaken, step to extend this notion to traditional industrial districts or modern clusters and to arrive at an idyllic, non-monetary form of communal economic activity. This inclination towards polarisation between ‘arm’s length exchange’ and collective interaction arises from the misleading way neoclassical economics rests on a massively under-socialised concept of humankind, something that interested, for example, Marshall (1919) and even later writers like Granovetter (1973) from the beginning. Contemporary economic geography written from

an evolutionary or at least mostly non-neoclassical perspective eschews that ‘desiccated calculating machine’ perspective on the wellsprings of human action. Rather it argues that

‘economic man’ (and woman) are profoundly social in their economic thought and action.

Some research finds that ‘social capital’ is a pronounced feature of market activity in which even the nearest to a caricature of a rational utility maximiser, the market ‘spot trader’, may

3 nevertheless use ‘swift trust’ (Sako, 1992) to gain an edge (Cooke & Clifton, 2004).

Interestingly, the most innovative firms are the least ‘neoclassical,’ having treble the social capital networks, both local and global, of the average firm.

Other social norms motivating economic action by firms include those identified by

Schumpeter (1975) as associated with innovation and entrepreneurship. Assume a discovery by the heroic innovator, whether a Nietzchean entrepreneur as in Schumpeter’s early work, or later the equally heroic but more team-based innovators in now-defunct corporate R&D laboratories. If radical and commercial the mere existence of that innovation attracts swarms of imitators seeking to appropriate an early surplus from ‘second-comer advantage’ (building on mistakes from the innovator’s ‘first-mover’ advantage). Although Schumpeter also failed to see the geographical implications of the quest for proximity to the innovators by the imitators, they are clear. Swarming is self-evidently one kind of spatial concentration activity that can give rise to clusters as entrepreneurs seek to ‘free-ride’ on waves of knowledge spillovers. Another, more common variant of such a ‘spin-in’ model is ‘spinout’, particularly from a founding firm. Among hundreds of cluster stories of this kind, the aforementioned

Belluno spectacles district, for example, originated with a contract dated 1878 where a local man, Angelo Frescura, in collaboration with Giovanni Lozza and Leone Frescura, opened a craft workshop for the production of spectacles near Calalzo, in Cadore. Cadore remains the historical heartland of the Belluno spectacles district and still the area with the highest concentration of companies.

Hence, tying together the variety of reasons for spatial concentration, including clustering, by firms in the same or similar sectors we may concur with the typology according to Gordon &

McCann (2000) for whom they are the following:

the proximity of firms induces a nexus of ‘Marshallian’ external economies from enhanced local skills supplies, cheap local infrastructure, specialised producer support services, and localised knowledge spillovers (see Caniëls & Romijn, 2005)

firms may be part of a regionalised or localised outsourcing system designed to generate ‘Toyotian’ logistical and transactional costs reductions that enhance productivity and quality through preferred supplier interactions

firms in proximity may seek to reap ‘Associational’ economic benefits from systemic

4 local and regional innovation and learning networks involving research institutes, industry associations, and governance measures (see also, Cooke & Morgan, 1998).

It is important to recognise there is a scale effect with each of these, contingent on both spatial and institutional factors. Thus ‘Marshallian’ districts tend to be small, even occupying

‘quarters’ of cities like Birmingham and Arezzo’s ‘jewellery quarters’ (De Propris &

Lazzereti, 2003; Lazzeretti, 2005), Florence’s art restoration quarter (Lazzeretti, 2003), or

Leipzig’s traditional ‘ graphische viertel

’ or ‘graphics quarter’ (Bathelt, 2002). They are also highly specialised. Marshall himself noted the high specialisation of specific small textile towns in northern England as between spinning and weaving, and coarse and fine weaving as a characteristic feature of industrial districts (Marshall, 1919). A Toyotan cluster, including satellites, is urban in scale and while specialised in, for example, automotive assembly covers a wide range of supply sectors. An ‘Associational’ system is likely to be regional in scale, and contain more than a single cluster. For example, Baden-Württemberg contains at least two differently-scaled and distinctive automotive clusters in Stuttgart (Porsche and Mercedes), a printing machinery cluster (in Heidelberg), a surgical instruments cluster (Pforzheim), and a machine tools cluster in the Black Forest. Institutionally speaking, co-ordination tends, according to Visser & Boschma (2004) to be cost-driven with ‘free-rider’ search characteristics prominent in ‘Marshallian’ systems, corporate and hierarchical in ‘Toyotan’ systems, and interactive with quality, technical knowledge, and price equally prominent in

‘Associational’ systems. One might characterise these governance regimes as typical, respectively, of liberal-market, developmental, and corporatist industrial systems more generally (Casper, Lehrer & Soskice, 1999).

Unravelling Porter’s Synthesis

Until its somewhat opportunistic discovery by the business school fraternity and Michael

Porter at Harvard Business School in particular, the study of such ‘district formation’

(Becattini, 2001) or ‘districtualisation’ processes as they are perhaps less elegantly described

(Varaldo & Ferrucci, 1996; Lazzeretti, 2003) was proceeding, with regional scientists and economic geographers of a heterodox stripe as unofficial observers (Cooke & da Rosa Pires,

1985; Scott, 1988). The publication of a significant synthesis of the Neo-Marshallian Italian research by Piore & Sabel (1984) also from Cambridge, Massachusetts, not Harvard but MIT,

and its rather insightful projection as a ‘second industrial divide’, away from the mass

5 production that caused the first industrial divide, into an era of neo-craft ‘flexible specialisation’. This specialisation was characteristic of industrial districts which gave further legitimacy to research in this field. Of particular importance and value in bridging the sentiments of Italian neo-craft production in districts and high technology production in modern clusters was Saxenian’s (1994) anatomisation and comparison of Silicon Valley’s success, associated with networking social capital, and Cambridge-Boston’s apparent demise due to the absence of such sociability. However, Saxenian did not deploy the language of

‘clusters’, that appellation being first used in a regional science context by Czamanski &

Ablas (1979) based on Czamanski’s (1974) study of industry clustering using linkage analysis. Indeed the term was a neologism evolved from the study of industrial complexes, mainly of large corporate entities and their linkage structures inspired by Perroux (1955), whose own growth pole concept derived from his application of Schumpeterian ‘swarming’ on to a spatial canvas, initially the Ruhr Valley. Thus from the Ruhr Valley to Silicon Valley, the cluster concept has been part of an ongoing synthesis and effort to decipher the lineaments of economic geography. Furthermore, the shadow of Schumpeter often hovers over the debate.

This was certainly the case with Porter (1990), who in various footnotes acknowledges a debt of gratitude, not to Czamanski but to Schumpeter and the Swedish economist Erik Dahmén for his version of the ‘cluster’. From Schumpeter, Porter benefited as follows:

‘My fundamental perspective is more Schumpeterian...than neoclassical.

Entrepreneurship and innovation prove central to national advantage. Why some firms and individuals innovate in particular industries, and why they are based in particular nations, will be the focus of much of what flows’ (Porter 1990, 778)

Therafter Porter reveals familiarity with classic location theory after Weber, Lösch,

Hirschman, Jacobs and Vernon concluding:

‘The economic theory of location shows how firms will locate close to each other to gain access to the broadest array of customers. The rationale here is similar’ (ibid. 789)

This leads to his acknowledgement of the importance for his idea of clusters of Dahmén’s work on the Swedish economy:

‘An early contribution is Dahmén’s 1950... concept of development blocks. Dahmén stresses the necessary link between the ability of one sector to develop and progress in another In his examples, Dahmén often also talks of stages or vertical activities within a given industry. This interesting work is suggestive that connections among industries can be important to achieving advantage’ (ibid. 790)

Finally, after reviewing the relevance to ‘clusters’ of research on innovation and technological interdependencies, citing authors like Lundvall, Rosenberg, Abernathy and

6

Utterback he concludes:

‘My theory integrates these sources and others into a broader framework...the local

‘diamond’ bears centrally on the learning and diffusion process in a national industry’

(ibid 791-792)

Hence at the stage of evolution in his thinking represented by Porter (1990) the die is more or less cast with all its flaws and confusions that remain in the later work and the diffusion, if not proselytisation of clusters and clustering to the policy world represented in Porter(1998). We can attempt to summarise Porter’s initial position as follows.

First, clustering is more Schumpeterian than neoclassical, but it retains the neoclassical perspective, which is that firms and individuals, not collectivities like networks or institutions, are the theoretical objects of interest in understanding economic growth dynamics.

Schumpeter offers an important window upon innovation that, Porter might add, neoclassical economics traditionally assumed away. The point of analysing economic growth dynamics is to understand and secure national (competitive) advantage. Competitive advantage occurs more in some nations than others but the problem is not to universalise it but to retain and develop it. Schumpeter’s insights into innovation and entrepreneurship are important for this.

Location theory also shows us that firms co-locate to maximise their market. Meanwhile

Dahmén stresses the way one sector can progress by selling into other sectors. This selling from one sector to another gives competitive advantage. This is achieved by the local

‘diamond’ (or cluster, with locally rivalrous firms, demanding customers, but also certain collective assets) that propels forward the national industry.

This seems a coherent viewpoint, but from only one highly specific position, which Porter

(1990) discusses at length in chapter 5, pp 210 -225. This is the only one of three industry accounts that is substantially place-based. It is the Italian ceramic tile industry, which in 1987 was 85% dependent on production and 75% for employment from one small town, Sassuolo, in Emilia-Romagna. Business school research is frequently criticised for its reliance upon case studies, and Harvard Business School has one of the most extensive business case study libraries on earth. The obvious danger with case studies is that unless they are incredibly representatively selected, they run the risk of the journalistic ‘fallacy of composition’ whereby one sensational case of something is taken as representing some general condition in the wider population. It is otherwise known as the problem of ‘the sample of one.’ Superficially,

Sassuolo fits the local ‘diamond’ notion almost too well, particularly in the way it accounts

7 for so much Italian national production, has final firms in competition, with sub-contractors selling contractually to them, and backward integration of the value chain from ceramics to the innovative design and global marketing of firing equipment needed to produce ceramics.

Nonetheless, as a reading of Russo’s (1985) classic article on Sassuolo shows, locally and nationally contingent events and processes like Italy’s ‘economic miracle,’ stupendous housing boom, and housing legislation allowing subsidies favouring use of ceramics, on the one hand, and industrial relations conflicts, on the other, created a space from which hitherto ceramics-free Sassuolo could benefit. Why Sassuolo? Because the appropriate clays only existed there and in the nearby Appenine mountains.

As well as skirting with the fallacy of composition, Porter’s words betray a major weakness in understanding of the issue of geographical scale. The local ‘diamond’ is thus unproblematically capable of influencing national industry. Indeed throughout most of the cluster passages of Porter (1990) the cluster definition stretches alarmingly from the local to the national and back again with bewildering facility. Of course, building on the previous point, where a local cluster has the inordinate impact that Sassuolo ceramics exerts upon the national ceramics sector, that may just be acceptable logic; however, most industry is nothing like that. So, initially at least, Porter’s cluster notion caused enormous confusion until finally, in Porter (1998) he more or less put things right with his spatially more informed definition of the cluster as:

‘...a geographically proximate group of interconnected companies and associated institutions in a particular field, linked by commonalities and complementarities’

(Porter, 1998, 199)

This conforms to dictionary definitions of ‘cluster’ as ‘concentration’, ‘clump’ or ‘bunch’, all denoting gathering or huddling in geographic space. Yet, having snatched coherence from the sea of confusion that Porter (1990) had created, he throws it away again in the very next line, revealing a Linus-like reluctance to dispense with the comfort blanket of universality:

‘The geographic scope of a cluster can range from a single city or state to a country or even a network of neighbouring countries’ (ibid, 199)

Naturally, this only makes things worse, almost risible, and something the Neo-Marshallian industrial district economists never once countenance in their carefully defined and meticulous studies, here elasticated into meaninglessness. For why bother troubling with a notion of geographic proximity when the next line qualifies the definition to encompass, let us say, the propinquity of Nome, Alaska and Key West, Florida. Even were one to allow that ‘a

network of neighbouring countries’ expresses a possible geopolitical or georegional entity of

8 sorts, the terminology merely betrays, in fact, the crudest kind of antediluvian geographical determinism. For why should the propinquity of shared borders denote either networking or, indeed clustering. So we feel justified in labelling Porter’s cluster concept his weakest link and a prime candidate for the designation ‘chaotic concept.’

This is not the final nail in the coffin of Porter’s cluster concept, for whether or not there is a reality behind what Porter is trying to get at, we argue, and have shown as do other contributors to this book with evidence, that clusters in the sense of industrial districts do, in fact exist. Evidence such as that found on the nature and extent of groups of collaborating firms that compete against other collaborating groups in the same district are exemplified with infinite pains in Becattini (2001) or Dei Ottati (2004) for the woolen textile district of Prato near Florence. Dei Ottati (1994) examined in depth the distinctive kinds of trustful and more sceptical relationships among individual firms, banks and intermediaries for the same place.

Astonishingly, in Becattini (2001) a detailed account is given of how, why and who the

Chinese ‘districts within a district’ came about in Prato from 1989-1993:

‘By December 1993 the Chinese community officially numbered over 1,400 residents, a neligible figure in itself for somewhere the size of Prato, but one that stands out noticeably if it is borne in mind that...in 1989 there were only 40...the Prato Chinese are part of a galaxy of similar communities that have settled in the surrounding area

(Camp Bisenzio, Signa, Lastra a Signa etc.) that can be reckoned to number some tens of thousands... this community has rapidly and efficiently inserted itself into Prato’s manufacture of clothing goods, where it has carved out a number of niches (handbags, gloves, etc.) in which with several hundred small firms, it has a far from negligible importance...’ (Becattini, 2001, 161-2)

Porter’s methodology excludes this kind of knowledge because he takes an operational definition of what counts as clustering , namely secondary data that show high location quotients for specific sectors and sub-sectors. Occasionally, as in Porter (1998) diagrams of cluster circuitry are drawn but they are not based on intrafirm interviews that would enable his researchers to acquire knowledge of precisely which interfirm transactions are, say, preferential contracts with neighbours, which are favour exchange relations with local significant others, whether a firm was a spinout from another in the locality, and what kinds of relationships exist, if any, with local business support agencies, lawyers, banks, venture capitalists and the like. In other words, Porter cannot prove that anywhere or anything he asserts to be a cluster actually is one. All that can be said from location quotient data is that there is a higher than average specific industrial agglomeration in location x or y, which actually does not get us very far beyond Weber or Lösch.

Three final qualifiers are, first, because of the static definition of cluster deployed by Porter

(1998) none of the dynamism that such spinout, networking, and project focused activity that

9 the Neo-Marshallians routinely find in industrial districts would be available to Porter’s methodology even were he bold enough to venture inside a few factory gates. Second, static cluster accounts give a foreshortened sense of the time it takes for clusters to form. Most of the Italian ones date to at least early postwar or the 1960s ‘economic miracle’ era and many say that they can be traced back to the Renaissance. Hence presenting clusters as a policy panacea is to engage in doubtful mis-selling, which policy organisations are beginning to discover, as we shall see. Finally, Porter’s definition is, as we have seen, a market-driven one with reliance on rivalry and competitive advantage. However, arguably some of the most interesting new cluster forms, such as those that typify biotechnology (e.g. Cooke, 2004a) are science-driven, not primarily market-driven. Indeed most firms in biotechnology clusters do not even make profits, but have discovered a new business model in which pharmaceuticals firms and research councils invest in ideas.

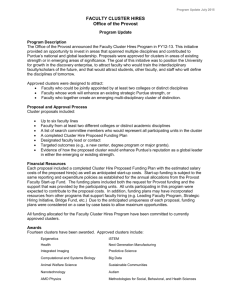

The Legacy for Policy

The marketing of the cluster idea to policy agencies was remarkably successful, as the thirtyfive strong client list in Porter (1998) testifies. However, while the jury was out regarding the success of cluster policies during most of the 1990s, in the current decade signs of dissatisfaction are appearing almost daily. One major source of disappointment derives from different aspects of the Monitor basic methodology. This is the consultancy arm of the Porter clusters research. Although Porter recognised despite what we have seen to be a faulty methodology that not all clusters are alike, the way Porter differentiates them is discursive and superficial. Thus they are asserted to ‘...vary in size, breadth, and state of development’ (ibid.

204). ‘Some clusters consist of small- and medium-sized firms.....Other clusters involve both large and small firms....’ (ibid. 204). Once again the reader is left wondering at the lack of self-critique on the part of the author of such trite observations, and even more so the absence of scepticism from the eager clients of such a meagre prospectus. As the first sub-heading of the ‘Clusters & Competition’ chapter in Porter (1998) displays with its question ‘What Is a

Cluster?’ the answer is, despite the obvious glosses regarding difference, a ‘one-size fits all’ definition.

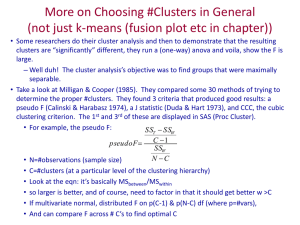

We may, in brief, identify seven key problems that have arisen from the implementation of

Monitor style cluster policies. Three recurring issues of cluster evaluation involve

understanding the additional impact generated by a cluster approach at the macro level

(impact on the regional or local economy), at the meso-level (on the cluster or sector in question) and on the micro level (on the individual business). Unless the policy applies to a

10 case like Sassuolo, which accounts for 85% of Italian ceramics production, it is no simple matter to measure the impact of a cluster policy. Even so, given that clustering involves more than simple agglomeration, it is probably only at the very narrowest margin that the impact of typical cluster policy support for better networking, joint marketing, or common purchasing initiatives can be measured, and then only at the level of firm performance aggregated up to cluster performance.

At the meso-level, some work has been conducted, most notably as reported by Brusco et al.

(1996) on all industrial districts in Emilia-Romagna benchmarked against Italian sectoral data.

Clusters performed better than their sector in terms of employee income, exports and average firm size according to this study. However, the panel methodology utilised to derive these conclusions is open to question as many panel members were closely associated with the clusters in question. Of course, separating out cluster policy effects from macro-economic effects such as a currency devaluation that occurred during the timescale of the study, is also no easy matter.

Third, at the firm level, what benefits do cluster policies bring to the firm that is located within one? This is unclear; but, it may be inferred from certain policy shifts observable among agencies that were early adopters of

Monitor’s

methodology where the rate of growth of existing firms, and even the rate of new firm creation have been disappointing. Two cases of such shifts, involving the same cluster sector – biotechnology – may be cited in support of the thesis that cluster policy has negligible effects on firm performance. These involve two early adopter territories, Scotland and the Basque Country. The latter hired Monitor to conduct the first scoping study for a Basque cluster strategy as early as 1990 (Cooke &

Morgan, 1998). Scottish Enterprise hired the same firm to map out its cluster strategy in 1993, although a pilot scheme involving promotion of biotechnology, semiconductors, food & drink, and energy clusters was first implemented in 1997. By 2003 both the Basque Ministry of Industry and Scottish Enterprise had launched new, non-cluster based knowledge commercialisation initiatives in these fields. The newly established BioBask initiative swiftly developed a basic research-led biotechnology strategy concentrating on research niches in proteomics. In six months a planned multi-storey car park was converted into top-grade wetlabs, advertisements were placed in Nature Biotechnology to recruit proteomics

biotechnologists worldwide and from two hundred applicants forty were selected. Three linked spinout firms occupy incubator space in the BioBask facility. In 2003 Scottish

Enterprise announced three Intermediary Technology Institutes, funded at £450 million over

11 ten years, one specialising in Life Sciences, the others in ICT and energy, to increase the rate of commercialisation of basic bioscientific and medical research. New firm formation is among the potential vehicles for achieving this (see Cooke, 2004b). In both cases disappointment at the long time-horizons and slow firm growth in this and the other cluster sectors prompted these drastic policy reviews and changes of direction.

A review of cluster challenges in Scandinavia showed the following issues have also been identified:

A lack of critical mass. How is it possible to sustain growth in a potential cluster?

The cluster’s focus is primarily local. How can it be integrated into national and international networks?

How can a new organisation be structured to maintain the benefits of vertical coordination and cooperation, yet avoid becoming bureaucratic?

How can the many initiatives be effectively coordinated and diverse interests appropriately balanced?

The review claims many other cluster practitioners seem to be facing these same challenges.

The review notes one reason why the cluster development processes often appear more straightforward than they actually are is the abundance of so-called best practice cases available. The descriptions are typically written with a focus on vision and strategy, but rarely results, and they typically disregard the obstacles encountered. One cluster presented as a success story that was cross-checked by the reviewers had actually been terminated due to organisational problems (Jensen, 2004).

The Asymmetric Knowledge Problem

Clearly clusters have been oversold. The nature of the marketing game and the appetite shown for new wonder growth products by economic policy makers as much as gardeners mean that there has long been the need for an objective assessment since cluster marketing is a paradigm case of asymmetric knowledge. In his classic article, Nobel laureate George Akerloff (1970) explored market imperfections and market failure from the perspective of asymmetric information. Asymmetric knowledge is similar except that knowledge implies meaning for action whereas information has more passive, absorption connotations. Still Akerloff’s key idea, which was to explore the nature of the market for ‘lemons’, is important in the cluster

policy concept. In American used-car business parlance a ‘lemon’ is a second hand car that

12 breaks down. The parallels are almost exact. In the economic development market, a new model from Italy arrives on the radar at precisely the time that the old models seem to have exhausted their attractiveness. The new model even seems to outpace the older one in nimbleness, flexibility and performance. The model is examined, tested, and found to be cheap to run, primarily requiring higher quality, more interactive drivers. Adaptations are made to suit the model to the American market and a sales drive is successfully launched.

However, neither the marketer nor the customer knows whether the model will work outside its native conditions, but the salesman doesn’t mind that since he has made his sale, leaving the poor customer to be the policy guinea pig. Needless to say, many customers will have bought ‘lemons’ as we have seen.

One important aspect of the model testing that is infrequently focused upon is the labour dimension. This is explored in this collection by Scott, anatomising the Hollywood film cluster. This is a specific type of cluster, unlike the Italian industrial districts in displaying an oligopolistic industry structure where global firms like Disney, Sony, and AOL Time-Warner co-exist and contract, in a Smithian division of labour, to a multitude of small and mediumsized enterprises. On the back of this dominant-dependent industry structure, Hollywood spans the globe as the greatest purveyor of what Adorno (1991) dubbed ‘the culture industry’ the world has ever known. However, it floats on a raft of regulations that, as Scott shows, began with the Paramount Decree in 1948 that started the break-up of the old verticallyintegrated studio system and helped introduce more vulnerable, limited contract employment.

Many fragmented worker organisations exist to seek to moderate highly insecure and segmented working conditions. Hollywood is thus an institutionalised form of asymmetric knowledge in which insecure workers must constantly be on their guard both informally and formally to retain access to the means to live. Politically this feature, shared with many kinds of clustering might be treated sceptically by better informed policy clients (Trigilia, 1990).

Of course as markets, clusters must be expected to display the negativities of asymmetric knowledge, as when they are said to be prone to problems of ‘lock-in’ due to inadequate attention to external shifts, changes or threats from market processes (Grabher, 1993).

Moreover where they are characteristically oligopolistic markets, as so clearly in the

Hollywood case, those on the wrong side of the knowledge asymmetry scales must make double the effort to access fragmentary crucial knowledge of where a future project or contract opportunity might lie. However, in fact, the imputed culture of clusters evidenced by

many detailed studies of particular cases like that of Prato by Becattini (2001) constitutes one great positive in dealing with asymmetric knowledge. It could be said that therein lies their greatest strength when they function as in the Italian case. So much are the Italian industrial districts centres of asymmetric, design-intensive, neo-craft knowledge that they attract global buyers from the world’s leading retail outlets as well as poor Chinese

13 immigrants to access the key knowledge for design-intensive textile, leather and garment production.

These are sources of distinction among both industrial districts and clusters that need to be made and understood. One early effort in this direction was that of Markusen (1996) who identified five types of industrial district:

Marshallian – small firms, localised investment links, preferred suppliers, labour market loyalty, flexible work regime

Marshallian (Italianate Variant) – with added co-operatiion, design-intensive work and collective institutions plus local government support

Hub-and-Spoke – Hollywood-like oligopolies plus suppliers, high intra-district trade, low co-opeartion among oligopolies

Satellite Platform – Externally-owned oligopolies, low co-operation, low social capital, strong government support

State Anchored – Government installations, scale economies, low local investment, strong external linkages

In truth, this typology has relatively little purchase on the matter in hand, which is differentiation of clusters, except to remind us of the variety of ways even large firms may utilise geographical proximity for reasons of history, policy, or comparative advantage. Thus

New Jersey’s ‘Medicine Chest of the World’ hosts the US headquarters of many global pharmaceuticals firms, but they scarcely interact, subcontract locally, or share facilities. They simply appropriated tax breaks and reduced rents across the Hudson River from New York.

Meanwhile Grangemouth in Scotland hosts many large, global petrochemical plants as a result of 1960s estuarine growth pole policy, whereby the UK government subsidised infrastructure costs for capital intensive production in specific oil-importing locations. Nowadays those firms are, in some cases, diversifying into ‘biologics’ as petrochemicals production migrates to the oil producing countries themselvses. Finally, military bases and capital cities come to mind as recipients of enormous taxpayer largesse with notable service, income and consumption spillovers for the luckily state-anchored districts, but not without vulnerabilities

when land rents rise or military policies shift, as with the Bush administration’s 2004 announcement of the withdrawal of 70,000 personnel from established military bases, especially in Germany.

14

Hence this is not a categorisation that proves of particular value to typologising clusters or even what are conventionally thought of as industrial districts. Indeed only two categories, that can easily be subsumed under a single Neo-Marshallian heading, refer to the heart of the matter. An attempt to do this in ways that are more germane to the perspective of this book was that of Bottazzi, Dosi & Fagiolo (2002). They also deployed a five category typology, with more variation on industrial agglomeration but some overlaps with Markusen even though there is no evidence they knew of her work. The categories are:

Horizontally Diversified – ‘Made in Italy’ districts with small firms producing high quality, design-intensive fashion products in traditional sectors like clothing, ceramics and jewellery;

Vertically Disintegrated – A variant on the ‘Made in Italy’ type with a

‘Smithian’ division of labour in localised supply chains, specialised with local input-output linkages and user-producer knowledge exchange, shoes, textiles and some clothing are produced in such districts;

Local Hierarchical – An ‘oligopolistic core’ connected to sub-contracting networks, as in transport equipment and white goods, for example;

Knowledge Complementarities – Science and engineering driven, as in Silicon

Valley and biotechnology clusters. Absent in Italy;

Path Dependent – Spatially inert agglomerations without any particular advantage from agglomeration in itself, e.g. Detroit as described by Klepper

(2000).

They point out that different types of agglomeration suggest different drivers for agglomeration itself taking into account also different sectoral specificities. To test this out they conduct a stochastic econometric test of various agglomeration hypotheses. Using Italian data this confirms a statistically significant advantage, measured in export performance, for the industrial district categories of agglomeration over the rest. The authors ascribe this advantage to two phenomena theoretically and empirically pronounced in such districts: sectoral patterns of knowledge accumulation; and localised knowledge spillovers of various kinds, from innovation to labour.

Building on such insights, this collection contains two papers, by Paniccia and Belussi respectively that further typologise and taxonomise industrial districts and clusters. The difference is typologies are ex ante and taxonomies ex post empirical analysis. Both deploy

15 wide ranges of criteria by which they differentiate categories and both draw, to a greater or lesser extent, upon the preceding analysis of Markusen but not that of their Italian colleagues.

For Paniccia the sixfold typology involves:

Semi-canonical – Small family firms, egalitarian, ‘star structure’ of dense networks;

Craft-based or urban – A strong nucleus of final firms sub-contracting to localised supply chains;

Satellite Platform or Hub & Spoke – Oligopolistic internal or external to the district;

Co-location Areas – A filière of reasonably large, vertically integrated firms producing different products in the same sector;

Concentrated or Evolutionary – ‘World’ or ‘regional product mandate’, as with the Belluno spectacles cluster with lead firms overseeing the whole production process from R&D to retailing, but outsourcing specific technology-intensive functions to local specialists

Science-based - Universities, large firms and small firms interact to commercialise sometimes short-lived discoveries from basic research in a cooperative, high social capital but ultimately highly marketised competitive context.

Belussi takes four of these categories for her taxonomy of industrial districts and clusters, correctly for her purposes conflating the first two and excluding ‘co-location areas’ in a tight conceptual model drawing on the many studies already conducted. She argues strongly for the geographic proximity connotation of clusters, thus moving the field forward conceptually from the period of Porterian confusion regarding that central issue. The task both for this taxonomy and Paniccia’s typology is to provide the theoretical groundwork for hypothesistesting research to determine the relative performance, efficiency and market effectiveness of the categories. A first approximation from Paniccia is that those clusters with high firm density will ceteris paribus out-perform the others, something, it will be recalled that is consistent with the Bottazzo, Dosi and Fagiolo (2002) conclusions.

References

16

Adorno, T.(1991) The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture , London, Routledge

Akerlof, G. (1970) The market for ‘lemons’: qualitative uncertainty and the market mechanism, Quarterly Journal of Economics , 84, 488-500

Bathelt, H. (2002) The re-emergence of a media industry cluster in Leipzig, European

Planning Studies , 10, 583-612

Becattini, G. (2001) The Caterpillar and the Butterfly , Florence, Felice le Monnier

Bottazzi, G, Dosi, G. & Fagiolo, G. (2002) On the ubiquitous nature of agglomeration economies and their diverse determinants: some notes, in A. Curzio & M. Fortis (eds.)

Complexity and Industrial Clusters , Heidelberg, Physica-Verlag

Brusco, S, Cainelli, G, Forni, F, Franchi, M, Malusardi, A. & Righetti, R. (1996) The evolution of industrial districts in Emilia-Romagna, in F. Cossentino, F. Pyke & W.

Sengenberger (eds.) Local and Regional Response to Global Pressure: the Case of

Italy and its Industrial Districts , Geneva, International institute for Labour Studies

Caniëls, M. & Romijn, H. (2005) What drives innovativeness in industrial clusters?

Transcending the debate, Cambridge Journal of Economics , 29, 497-515

Casper, S, Lehrer, M. & Soskice, D. (1999) Can high technology industries prosper in

Germany? Institutional frameworks and the evolution of the German software and biotechnology industries, Industry & Innovation , 6, 5-24

Coase, R. (1937) The nature of the firm, Economica , 4, 386-405

Coleman, J. (1988) Social capital and the creation of human capital, American Journal of

Sociology , 94 (supplement), S95-S120

Cooke, P. & Da Rosa Pires, A. (1985) Productive decentralisation in three European regions,

Environment & Planning A, 17, 527-544

Cooke, P. & Morgan, K. (1998) The Associational Economy , Oxford, Oxford University Press

Cooke, P. & Clifton, N. (2004) Spatial variation in social capital among UK small and medium-sized enterprises, in H. de Groot, P. Nijkamp & R. Stough (eds.)

Entrepreneurship and Regional Economic Development: a Spatial Perspective ,

Cheltenham, Edward Elgar

Cooke, P. (2004a) Regional knowledge capabilities, embeddedness of firms and industry organisation: bioscience megacentres and economic geography, European Planning

Studies , 12, 625-642

Cooke, P. (2004b) Integrating global knowledge flows for generative growth in Scotland: life sciences as a knowledge economy exemplar, in OECD (ed.) Global Knowledge Flows and Economic Development , Paris, OECD

Chesbrough, H. (2003) Open Innovation , Boston, Harvard Busines School Press

Czamanski, S. (1974) Study of Clusters of Industries , Institute of Public Affairs, Halifax,

Dalhousie University

Czamanski, S. & Ablas, L. (1979) Identification of industrial clusters and complexes: a comparison of methods and findings, Urban Studies , 16, 61-80

De Propris L. & Lazzeretti, L. (2003) The Birmingham Jewellery Quarter: A Marshallian

Industrial District, Working Paper Series 2003-17 , Birmingham Business School,

University of Birmingham

Dei Ottati, G. (1994) Co-operation and competition in the industrial district as an organisational model, European Planning Studies , 2, 371-392

Dei Ottati, G. (2004) The remarkable resilience of the industrial districts of Tuscany, in P.

Cooke, M. Heidenreich & H. Braczyk (eds.) Regional Innovation Systems , 2 nd Edition,

London, Routledge

Dosi, G. (1988) Sources, procedures and microeconomic efects of innovation, Journal of

Economic Literature , 26, 1120-1171

Gordon, I. & McCann, P. (2000) Industrial clusters: complexes, agglomeration and/or social networks? Urban Studies , 37, 513-532

Grabher, G. (1993) (ed.) The Embedded Firm: On the Socio-Economics of Industrial

Networks , London, Routledge

Granovetter, M. (1973) The strength of weak ties, American Journal of Sociology , 78, 1360-

1380

Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death & Life of Great American Cities , New York, Random House

Jensen, B. (2004) Cluster Processes Typically Disregard Obstacles , Copenhagen, Oxford

Research

Klepper, S. (2000) Entry By Spinoff , Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University

17

Lazzeretti, L. (2003) City of art as a high culture local system and cultural districtualisation process: the cluster of art restoration in Florence, International Journal of Urban &

Regional Research , 27, 635-648

Lazzeretti, L. (2005) Density dependent dynamics in the Arezzo jewellery district, European

Planning Studies , (forthcoming)

Marshall, A. (1919) Industry & Trade , London, Macmillan

Markusen, A. (1996) Sticky places in slippery space: a typology of industrial districts,

Economic Geography , 72, 293-313

Penrose, E. (1959) The Theory of the Growth of the Firm , Oxford, Oxford University Press

Perroux, F. (1955/1971) Note on the Concept of Growth Poles, in T. Livingstone (ed.)

Economic Policy for Development: Selected Readings , Harmondsworth, Penguin

Piore, M. & Sabel, C. (1984) The Second Industrial Divide , New York, Basic Books

Porter, M. (1990) The Competitive Advantage of Nations , New York, The Free Press

Porter, M. (1998) On Competition , Boston, Harvard Business School Press

Richardson, G. (1972) The organisation of industry, Economic Journal , 82, 883-896

Russo, M. (1985) Technical change and the industrial district: the role of interfirm relations in the growth and transformation of ceramic tile production in Italy, Research Policy , 14,

329-343

Sako, M. (1992) Prices, Quality & Trust , Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Saxenian, A. (1994) Regional Advantage , Cambridge, Harvard University Press

Schumpeter, J. (1975) Capitalism, Socialism & Democracy , New York, Harper

Scott, A. (1988) New Industrial Spaces , London, Pion

Teece, D. & Pisano, G. (1994) The dynamic capabilites of firms: an introduction, Industrial and Corporate Change , 3, 537-56

Trigilia, C. (1990) Work and politics in Third Italy’s industrial districts, in F. Pyke, G.

Becattini & W. Sengenberger (eds.) Industrial Districts & Inter-firm Co-operation in

Italy , Geneva, International Institute for Labour Studies

Varaldo, R. & Ferrucci, L. (1996) The evolutionary nature of the firm within industrial districts, European Planning Studies , 4, 27-34

Visser, E. & Boschma, R. (2004) Learning in districts: novelty and lock-in in a regional context, European Planning Studies , 12, 793-808

Winter, S. (2000) The satisficing principle in capability learning, Strategic Management

Journal , 21, 981-996

Young, A. (1928) Increasing returns and economic progress, Economic Journal , 38, 527-542

Zollo, M. & Winter, S. (2002) Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities,

Organisation Science , 21, 981-996