Eric Helke

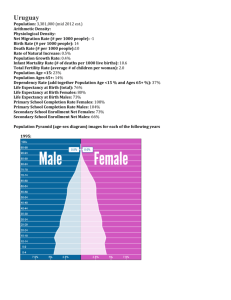

advertisement

Gender differences in risk-taking Eric Helke Introduction to the topic: Many analytical and statistical reviews of data collected from sources concerning traumatic events have returned relatively significant, but not overly surprising results. As we might guess from reading the news or other publications, men are overall more prone to accidents or trauma involving avoidable risky behavior than women. In particular, men are involved in more arrests, more automobile deaths (US Dept. of Transportation), and more drowning or poisoning deaths than women (Waldron et al., 2005). Of course, these alarming statistics lead psychologists (and decision theorists alike!) to beg the question: what could possibly cause such a noticeable gender difference across different domains and from studies conducted around the world? The difficulty in answering such a question lies in determining exactly where we should look for these differences. Further, once we have discovered some general aspect in which we see gender differences, why are those caused in the first place? We could consider many options such as upbringing, past traumatic events, hormone counts, or other possible causes for risk-seeking behavior! I have set forth to find or hypothesize an answer to any number of these questions by investigating and analyzing studies performed by qualified individuals in the field of decision psychology. I am particularly interested in narrowing the list of possible gender differences between men and women, even if many different sources of differences can be found. If there is little evolutionary evidence yet lots of cognitive evidence toward gender differences, I would focus on the evolutionary differences for example. These are only two of many examples of investigations that may help us to better understand the cause of gender differences! Literature Review: Before passing any study conclusions into fact, we must make sure that the definitions of “decision” and “risk” are clear and are similar across the studies. A decision, for the purposes of this tutorial, can be defined as a voluntary choice, assuming the subject in question is a rational being (i.e. human) and informed of all the possible outcomes of their decision (Byrnes et al., 1999). The term “risk” takes this definition further, and introduces the dimensions of gain or loss, or of simply avoiding any type of loss in the first place. Researchers typically refer to constructs such as goals, outcomes, options, or values when they are referring to risks or decisions. Based on the types of research pertaining to this subject, I have roughly categorized three types of theories regarding differences in “risk taking” or “risk avoidant” strategies: 1. Differences between people who regularly take risks and those who regularly avoid risks. 2. Differences between situations either promote risk-taking or promote risk-aversion. These theories are the ones that give trouble to the normative theorists that are primarily concerned with studying the aspects of the other two theories… 3. Differences among people and their reactions in situations that promote risk-taking. These primarily explain those odd situations where one might act completely out of character… Additionally, societal taboos and perceived social roles in society may play a big part in how both genders perceive risks and how often they engage in risky behavior. In a 2006 study conducted by Harris, Jenkins and Glaser, participants answered a questionnaire regarding the frequency of risky behaviors or their chances of engaging in these behaviors. Men scored consistently higher (more likely to participate in said activity) in the domains of gambling, health, and recreation, yet scored roughly the same as women on the social domain. Harris et al. concluded that the perceptions of the probability of negative outcomes resulted in this answer set, and that males’ assessments of possible negative results of risky behavior seems to be lessened or buffered when compared to females’ assessments. This means females approach known risk with a more cautious (and often realistic) forecasting method. On this same questionnaire, men appeared to answer with more “defending” ideas when asked why they would engage in risky behavior. Women gave more passive answers when asked to explain their reasoning for engaging in risky behavior. Buss (2003) attributes this type of risk-processing to evolutionary theory, suggesting that males perceive risk as less likely to happen because males have evolved over time constantly not having to worry about their offspring as much as females must. A male can reproduce in minutes, while a female must go through a 9-month period of carrying the baby before birth. Furthermore, males typically spend less time around their children after birth and do not have to constantly monitor for possible environmental factors that may harm their child. Females (especially those with children) are constantly exposed to situations which require them to monitor for risks in order to protect offspring, thus becoming more cautious over time. Not only do our perceptions drastically change our views regarding the outcomes of decisions, but also the perceived severity of possible events. Harrant (2008) concluded that in the face of grave circumstances such as impending death (AIDS in his study), women are more willing to jeopardize their chance of either receiving more money from the federal government with the other choices of remaining at the same government subsidy, or losing all funding if they are rejected from their proposal to the French court. In fact, women were almost three times as likely as men to choose to jeopardize their standard subsidy from the government for the chance at getting either more money or nothing at all. As one might conclude from the various studies on the topic, it seems there is no set pattern or means by which males show significant difference from women in engaging in risky behavior. This of course begs researchers to further pursue the topic given what we already know in pursuit of a better definition of gender differences in risk perception and analysis. Relationship to Other Topics: The topic of gender differences in decision making with risks present is an extremely useful study for psychology and decision theory. Any cognitive or physical differences between males and females would be interesting to compare against current theories of decision-making. Further, the social and societal implications of reducing risky behavior would benefit not only men but women. The research discoveries discussed in this paper relate to decision theory in that they involve value and decisions under both certainty and uncertainty. Both utility theory and prospect theory seek to prescribe a set of rules to general human behavior as it relates to assigning values to outcomes and then deciding which to pursue. We must keep in mind that much of decision theory is devoted to studying situations in which we choose to act “irrationally,” as opposed to studying the situations in which we act in a rational manner. In situations considered safe or devoid of risk, we see that people often still make “irrational” judgments, acting against how one might think they would behave in the particular situation, resulting in both good and bad outcomes. Often this behavior is due to the relative value that one might place on any one of the possible outcomes of their decision. Risk-taking behavior or thrill-seeking might be considered irrational, for example, because of their perception of risk or of a negative outcome. In order to summarize human decision-making behavior into a single, all-encompassing (or at least mostly true) theory, we must transcend the differences among the human race in order to discover the one element of decision-making that we have in common. Further research must also be reviewed from the meliorist, apologist and Panglossian points of view in order to effectively categorize the results as they affect various dimensions of the study of psychology, public policy, social and personal life. Works Cited: Abbott-Chapman, J., Denholm, C., & Wyld, C. (2008). Gender differences in adolescent risk taking: Are they diminishing? An Australian intergenerational study. Youth& Society, 40(131), 131-154. Retrieved from Sage Publications database. Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 25(3), 367-383. Coid, J., Yang, M., Ullrich, S., & Zhang, T. (2009). Gender differences in structured risk assessment: Comparing the accuracy of five instruments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 337-348. Harrant, V. & Vaillant, N. G. (2008). Are women less risk aversive than men? The effect of impending death on risk-taking behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29, 396-401. He, X., Inman, J. J., & Mittal, V. (2008). Gender jeopardy in financial risk taking. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, 414-424. Meier-Pesti, K. & Penz, E. (2008). Sex or gender? Expanding the sex-based view by introducing masculinity and femininity as predictors of financial risk taking. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 180-196. Stoltenberg, S. F., Batien, B. D., & Birgenheir, D. G. (2008). Does gender moderate associations among impulsivity and health-risk behaviors? Addictive Behaviors, 33, 252-265.