Risk-Taking and the Media Perspective Peter Fischer, Evelyn Vingilis,

advertisement

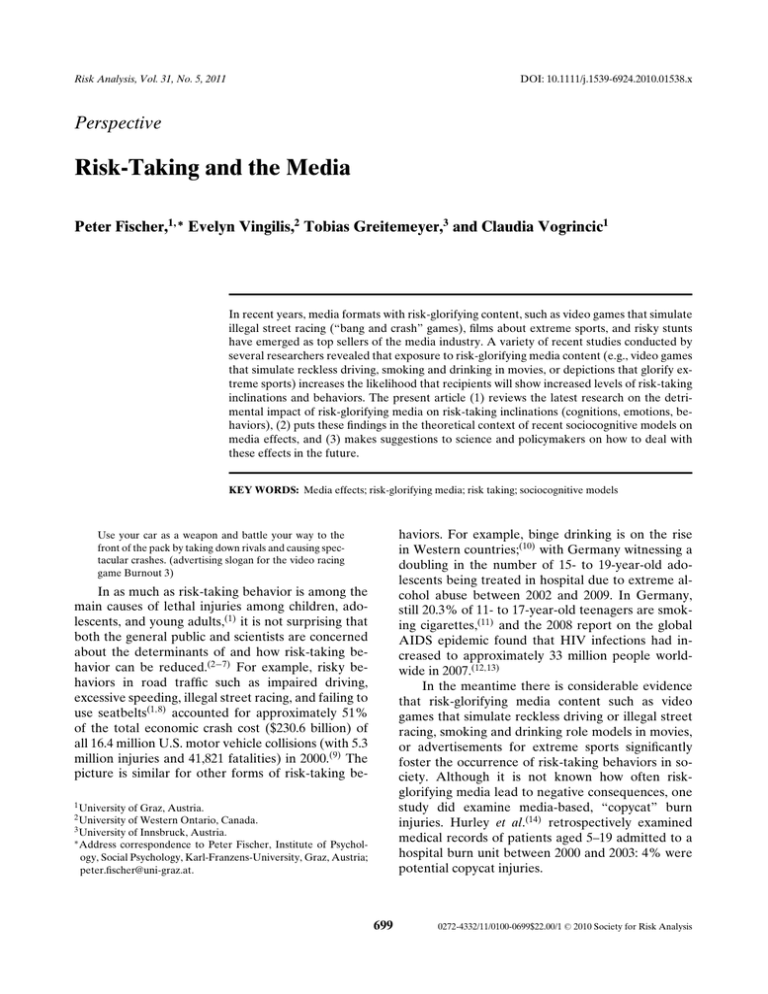

Risk Analysis, Vol. 31, No. 5, 2011 DOI: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01538.x Perspective Risk-Taking and the Media Peter Fischer,1,∗ Evelyn Vingilis,2 Tobias Greitemeyer,3 and Claudia Vogrincic1 In recent years, media formats with risk-glorifying content, such as video games that simulate illegal street racing (“bang and crash” games), films about extreme sports, and risky stunts have emerged as top sellers of the media industry. A variety of recent studies conducted by several researchers revealed that exposure to risk-glorifying media content (e.g., video games that simulate reckless driving, smoking and drinking in movies, or depictions that glorify extreme sports) increases the likelihood that recipients will show increased levels of risk-taking inclinations and behaviors. The present article (1) reviews the latest research on the detrimental impact of risk-glorifying media on risk-taking inclinations (cognitions, emotions, behaviors), (2) puts these findings in the theoretical context of recent sociocognitive models on media effects, and (3) makes suggestions to science and policymakers on how to deal with these effects in the future. KEY WORDS: Media effects; risk-glorifying media; risk taking; sociocognitive models haviors. For example, binge drinking is on the rise in Western countries;(10) with Germany witnessing a doubling in the number of 15- to 19-year-old adolescents being treated in hospital due to extreme alcohol abuse between 2002 and 2009. In Germany, still 20.3% of 11- to 17-year-old teenagers are smoking cigarettes,(11) and the 2008 report on the global AIDS epidemic found that HIV infections had increased to approximately 33 million people worldwide in 2007.(12,13) In the meantime there is considerable evidence that risk-glorifying media content such as video games that simulate reckless driving or illegal street racing, smoking and drinking role models in movies, or advertisements for extreme sports significantly foster the occurrence of risk-taking behaviors in society. Although it is not known how often riskglorifying media lead to negative consequences, one study did examine media-based, “copycat” burn injuries. Hurley et al.(14) retrospectively examined medical records of patients aged 5–19 admitted to a hospital burn unit between 2000 and 2003: 4% were potential copycat injuries. Use your car as a weapon and battle your way to the front of the pack by taking down rivals and causing spectacular crashes. (advertising slogan for the video racing game Burnout 3) In as much as risk-taking behavior is among the main causes of lethal injuries among children, adolescents, and young adults,(1) it is not surprising that both the general public and scientists are concerned about the determinants of and how risk-taking behavior can be reduced.(2−7) For example, risky behaviors in road traffic such as impaired driving, excessive speeding, illegal street racing, and failing to use seatbelts(1,8) accounted for approximately 51% of the total economic crash cost ($230.6 billion) of all 16.4 million U.S. motor vehicle collisions (with 5.3 million injuries and 41,821 fatalities) in 2000.(9) The picture is similar for other forms of risk-taking be1 University of Graz, Austria. of Western Ontario, Canada. 3 University of Innsbruck, Austria. ∗ Address correspondence to Peter Fischer, Institute of Psychology, Social Psychology, Karl-Franzens-University, Graz, Austria; peter.fischer@uni-graz.at. 2 University 699 C 2010 Society for Risk Analysis 0272-4332/11/0100-0699$22.00/1 Fischer et al. 700 Inspired by media violence research (which provided strong evidence that violent media causally increases aggression; see Anderson et al. 2010),(15) an emerging field of research has been investigating whether similar causal links can be found between exposure to risk-glorifying media content and increased risk-taking inclinations. This expectation has been confirmed: several types of media (video games, films, TV shows, newspaper articles) that depict risk taking in a positive light causally increase risk-promoting cognitions, emotions, and behaviors.(16−18) The present article reviews recent research on the impact of risk-glorifying media content on risk-taking inclinations, identifies underlying psychological processes, and integrates these findings into a new theoretical perspective based on sociocognitive theories. 1. CORRELATIONAL AND EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH ON RISK-GLORIFYING MEDIA EFFECTS The current perspective article works with a definition suggested by Ben-Zur and Zeidner:(2) “Risk taking refers to one’s purposive participation in some form of behavior that involves potential negative consequences or losses (social, monetary, interpersonal) as well as perceived positive consequences or gains” (p. 110). Risk-taking behaviors can be observed in a variety of domains, such as unhealthy living (drugs, alcohol, smoking), promiscuous sexuality (unprotected sex, promiscuity), road traffic (e.g., reckless driving, street racing, driving without seat belts), or dangerous sport activities (e.g., solo climbing without security ropes).(2) Can risktaking inclinations and behaviors be influenced by risk-glorifying media content? The media that surrounds us is full of riskglorifying depictions. For example, in the famous TV show Jackass (MTV), young men engage in extremely dangerous activities, such as risky driving, downhill racing with skateboards, risky stunts, selfexperimentation with weapons and electro shocks, etc. All these dangerous activities are performed in a rather “funny” and thus risk-glorifying way. In addition, we find risk-glorifying media content in music lyrics, car advertisements, and video games. Moreover, Vingilis and Smart(19) have suggested that illegal street racing has increased because of the promotion of a risk-glorifying street racing culture in the media, including video games, movies, and car advertisements. This risk-promoting culture is even communicated to young children with cartoons such as Speed Racer, and there is anecdotal evidence of “copycat stunts.”(19) For example, the public recently became aware of the potentially detrimental effects of risk-glorifying video racing games (which simulate street racing in a photographically realistic video game environment) when the popular racing game, “Need for Speed,” was found in the vehicle of one of two young male drivers who appeared to be racing in Toronto on January 26, 2006, following a collision that led to the death of a taxi-driver.(19) This and other similar events have led policymakers to wonder whether playing racing games that promote illegal street racing might motivate players to engage in real-life street racing and other forms of risky driving. For example, Australian road safety authorities tried to ban a video game on street racing through virtual images of Sydney, Australia (cited in Vingilis & Smart, 2009(19) ), which was promoted by the following advertisement: “Burn up a storm past famous landmarks such as the Opera House and Sydney Harbour.” Do games like these and other forms of risk-glorifying media increase risky driving and other forms of risk taking? In the following sections we review the empirical evidence on the question whether such risk-glorifying depictions in the media indeed increase recipients’ inclinations to risk taking. 1.1. Correlational Research A variety of correlational studies indicate that increased levels of exposure to risk-glorifying media are associated with increased levels of risk-taking inclinations and actual risk-taking behaviors. For example, Beullens and van den Bulck(20) obtained data from 2,194 adolescents and found a positive correlation between exposure to risk-glorifying media and positive attitudes toward both risky driving and willingness to take risks in traffic situations (e.g., driving while impaired). Further positive associations between consumption of risk-glorifying media content and willingness to take risks have been found for viewing images of smoking on television and starting to smoke;(21−23) exposure to alcohol advertising and adolescent alcohol consumption;(24) and adolescents’ exposure to sexual media stimuli and actual sexual activity.(25) Fischer et al. (2007, Study 1) also found that weekly frequency of playing racing games was significantly positively associated with self-reported competitive driving, obtrusive driving, and motor vehicle collisions, as well as negatively associated with Risk-Taking and the Media cautious driving.(17) In a similar study, Kubitzki(26,27) found that among 657 13- and 17-year-old participants, there was a positive association between consumption of risk-glorifying racing games and illegal underage driving. Findings from longitudinal studies also support the assumption that consumption of risk-glorifying media content is positively associated with risktaking inclinations and behaviors. For example, Wills et al.(28) investigated a sample of 961 young adults and observed that prior exposure to alcohol depictions in movies predicted both level of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems later in the life course.(29−31) Longitudinal effects of riskglorifying media content were also observed for smoking. In a sample of 2,614 5th–8th graders, Wills et al.(32) found that exposure to smoking in movies significantly predicted actual smoking behavior and smoking inclinations 18 months later (see also TitusErnsthoff et al.(33) ). Finally, similar longitudinal effects were found for exposure to sex on television and initiation of sexual behavior.(34) In sum, both correlational and longitudinal studies support the hypothesis that there is a substantial positive association between being exposed to risk-glorifying media content and subsequent risk-taking inclinations and behaviors. 1.2. Experimental Research Experimental research examines whether exposure to risk-glorifying media causally leads to increased risk-taking inclinations.(17,35,36) In the standard experimental study, participants are first exposed to either risk-glorifying media content (e.g., movies that portray people who perform risky behaviors positively; e.g., Hines et al.;(35) Kulick & Rosenberg;(37) risk-glorifying pictures of extreme sports; Fischer et al.;(16) or video games that simulate reckless driving and illegal street racing; Fischer et al.(18) ) or non-risk-glorifying media content. Afterwards, indicators of risk-taking inclinations and/or behaviors are measured. Classic indicators utilized are degrees of cautiousness in driving simulators,(38) risk tolerance in simulated critical road traffic situations;(17) the accessibility of risk-positive cognitions and emotions;(16) as well as the individual inclination to take physical risks.(35−36) By using an experimental paradigm, several authors have consistently gathered causal evidence that individuals exposed to risk-glorifying media content react by exhibiting in- 701 creased risk-taking inclinations on cognitive, affective, and behavioral levels. For example, Fischer and colleagues(17,16,18) undertook a systematic experimental investigation of whether exposure to risk-glorifying video racing games increases individuals’ inclination toward risk taking. Video racing games (also called virtual driving games or bang and crash games; e.g., “Need for Speed,” “Burnout,” or “Midnight Racer”) have emerged as top-sellers in the video game industry. Within photographically realistic virtual environments, players race through regular urban and suburban traffic. Driving actions often include competitive and reckless driving, speeding and crashing into other cars or pedestrians, or performing risky stunts with the vehicle. The authors showed that a 20minute session playing this type of game (compared to non-risk-related titles) increased the accessibility of risk-positive cognitions and emotions and led to increased behavioral risk taking in a subsequent simulated critical road traffic situation (WRBTV). The use of this well-established reaction time based risk-tolerance task (WRBTV; Vienna Test System by Schuhfried, 2006) made these results particularly concerning. This measure is standardized and widely accepted for measuring risk taking, specifically willingness to take risks in critical, dangerous road traffic situations. It has been successfully employed in traffic psychology (e.g., it has 89% accuracy in identifying multiple motor vehicle collision drivers). In a recent series of studies, Fischer et al.(18) showed that playing video racing games also increases blood pressure, sensation-seeking, and attitudes toward risky driving. Two studies included a time lag of 15 minutes or 24 hours between playing the games and the reaction time task, but both showed that consumption of risk-promoting racing games increases risk-taking inclinations. Finally, Fischer and colleagues (2009, Study 3) also found that playing risk-glorifying video racing games (vs. non-risk-related neutral games) led to riskier decision making (e.g., financial decisions), providing first evidence that the effects of risk-glorifying media content on risk taking are not necessarily domain specific. That is, risk-glorifying media content in one domain (i.e., risky driving) appear to carry over to distinct forms of risk-taking behavior (i.e., risky financial decisions). Similar experimental effects have been observed for health-related behaviors, such as alcohol consumption or smoking. For instance, a study conducted by Kulick and Rosenberg(37) revealed that participants who were exposed to movie sequences 702 featuring positive images of drinking exhibited more positive alcohol outcome expectancies than participants in a control condition who were not exposed to alcohol-positive imagery. Potts et al.(36) found a similar risk-glorifying media effect within a sample of young children. These authors assigned 6- and 9-year-old children to one of three different conditions: television programs with frequent physical risk taking, programs with infrequent physical risk taking, or no television programs at all. Afterwards, the children reported on a self-report measure their willingness to take physical risks. In line with a riskglorifying media effect, Potts et al.(36) found that children who had watched TV programs with frequent risk taking reported elevated levels of willingness to take physical risks compared to those who watched programs with infrequent risk-taking depictions, or those who saw none at all. Finally, similar effects have been also observed for smoking. Hines et al.(35) instructed participants to rate well-known movie actors who had either smoked or not in a viewed film sequence. The authors found that participants who saw the smoking scene reported greater likelihoods of actually smoking in the future than those who had witnessed the nonsmoking film sequences. In sum, there is accumulated evidence that exposure to risk-glorifying media increases risk-taking cognitions, emotions, and behaviors (for a meta-analysis, see also Fischer et al.(39) ). Finally, Fischer et al.(16) experimentally investigated the impact of risk-glorifying pictures and film sequences about extreme sports on risk-positive cognitions and attitudes toward risk taking. The authors exposed participants either to pictures of high-risk sports (e.g., free climbing, ski stunts) or risk-neutral pictures. Participants who were exposed to the riskpromoting pictures indicated a greater accessibility of risk-positive cognitions and a more positive attitude toward risk taking than participants who were exposed to the risk-neutral pictures. The same authors also used risk-promoting film sequences (i.e., sport stunts, risky scenes from a James Bond movie as well as from the MTV series Jackass) versus riskneutral film sequences and measured participants’ driving behavior in a driving simulation task. Participants who saw the risk-promoting film sequences were more inclined to risky driving than participants who were exposed to the risk-neutral stimuli. In sum, there is considerable evidence that risk-glorifying media content causally increases risk-promoting cognitions, emotions, and behaviors. Fischer et al. 2. UNDERLYING PSYCHOLOGICAL PROCESSES: SOCIAL LEARNING, PRIMING, AND SELF-CONCEPT The most prominent theoretical approach to media effects falls under the rubric of social-cognitive information processing theories, although most research on this model has been conducted in the context of violent media effects.(15,40) Anderson and Bushman(40) have integrated domain-specific theories of aggression into a framework called the General Aggression Model (GAM), which is based on social cognitive models incorporating social learning;(41) the “social-cognitive model of media violence”;(42) social information processing;(43) the “excitation transfer model”;(44) as well as the “Cognitive Neoassociationist Model.”(45) GAM postulates a multistage process whereby person and situation factors influence outcome behaviors through the internal states of cognitions, affect, and arousal that they create.(40,46) For example, violent media can influence aggression by priming aggressive thoughts or scripts through the process of spreading activation along associative neural pathways to other brain nodes representing aggressive thoughts, expectations, beliefs, and affect related to violence, and can thereby provide the initial trigger for aggressive behavioral responses. GAM also explains how processes of imitation, arousal, and excitation transfer, long-term learning, norm changes, and emotional desensitization can be induced by violent media, and thus lead to elevated levels of aggression in the recipient(40) (for an overview, see also Anderson et al.(15) ). Recently, Buckley and Anderson(47) expanded the GAM into a General Learning Model (GLM) to address not only the effects of exposure to violent media but also nonviolent media. GLM assumes that input variables (personal and situational) elicit behavioral responses through a person’s internal state (cognition, affect, and arousal). Unlike the GAM, however, the GLM stresses the importance of the media content. In fact, whereas exposure to antisocial media evokes aggression and aggressionrelated variables, exposure to prosocial media has been shown to instigate prosocial outcomes.(48−53) Lending further evidence to the validity of the GLM, it appears that exposure to risk-glorifying media promotes risk-taking inclinations. In support of the theoretical perspective of GAM and GLM, risk-glorifying media content increases risk-promoting cognitions and emotions Risk-Taking and the Media (Fischer et al.(17) Study 2; Fischer et al.(18) Study 4), which mediates inclinations towards risky decision making (Fischer et al.(16) Study 3). These findings are consistent with priming explanations of media effects derived from sociocognitive models.(53) However, Fischer et al.(18) argued that self-relevant processes might be especially important for explaining the effects of risk-glorifying video games on risk taking where participants are actively involved in the game content (in contrast to the effects of passive media consumption, such as viewing pictures or reading articles that glorify risk taking). Actively playing video games has a variety of implications for the self. For example, video games should lead to stronger self-involvement because the player actively controls the game character and makes vicarious decisions for it. In addition, video games systematically reinforce the player’s self-esteem by providing positive feedback (game score); social status (players tend to compare their game skills with each other; see especially online games); and feelings of self-competence in case the player masters a specific game level.(54) In line with this reasoning, active (such as video games) relative to passive (such as television and movies) exposure to violent media has been shown to have considerably larger effects on aggressive behavior.(55) So far, however, the psychological mechanism underlying this effect has not been directly addressed;(56) this was done by Fischer et al.(18) In support of these self-based assumptions, they found that changes in the automatic self-concept and associated self-perceptions play an important role in the context of risk-glorifying video games: participants who played a racing game perceived themselves more as a reckless driver and also evaluated reckless driving more positively. In contrast, changes in arousal, risk-promoting cognitions and emotions, and blood pressure did not mediate the basic effect. The risk-promoting effects of racing games on a behavioral reaction level only occurred when participants played racing games that reward traffic violations and when the individual was an active player of such games rather than a passive observer, which further supports the assumption that racing game consumption changes self-perceptions. In other words, the racing game effect requires the player to perceive that he or she is actively involved in breaking traffic rules, which leads to the self-perception that one is a reckless driver, and thus finally to more risk taking. In sum, from this new self-based theoretical perspective on media effects it appears that mostly 703 the effects of passive risk-glorifying media (pictures, films) are mainly driven by priming effects. That is, risk-glorifying images increase the accessibility of positively risk-related cognitions and emotions, which in turn increases the probability that actual behavioral risk taking occurs.(16) In contrast, the effects of active risk-glorifying media formats (video games) are mainly driven by a change in the perceived selfconcept. Players of video racing games positively perceive themselves more as reckless drivers and thus show increased risk taking in simulated critical road traffic situations.(18) In our opinion, this is a new theoretical perspective on media effects and the self, which should be taken up by future research. 3. CONCLUSIONS, FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR THEORY AND RESEARCH, AND SOCIETAL AND PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS The present article (1) reviewed the latest research on the detrimental impact of risk-glorifying media on risk-taking inclinations (cognitions, emotions, behaviors), (2) put these findings in a theoretical context of sociocognitive theories on media effects, and (3) makes suggestions to science and policymakers on how to deal with these effects in the future. There are important themes for future directions. First, clarification is needed on whether consumption of risk-glorifying media leads to increased risk taking in actual road traffic (which is difficult because of ethical restrictions). Although recent research used highly valid and reliable instruments for measuring risk tolerance in road traffic, future research should identify even more realistic ways to measure risk taking in road traffic. Second, there is initial evidence that the effects of risk-glorifying media contents are not domain specific. Future research should investigate whether carry over effects can also be found for other forms of risk-glorifying media formats as well as other types of risk-taking behavior. Third, it is important to further investigate the duration of these risky media effects. Although Fischer et al.(18) found that the effect can still be found after 24 hours, more evidence should be gathered (e.g., in longitudinal or cross-lagged panel studies). Fourth, it is important for future research to gain insight into the brain correlates of risk-taking behaviors that are triggered by risk-glorifying media contents (functional magnetic resonance imaging Fischer et al. 704 (fMRI), electroencephalogram (EEG) order to further specify the underlying psychological processes. The results of this research can inform various educational, legislative, and regulatory policies. For example, some jurisdictions have self-regulatory codes to govern advertising of motor vehicles “to ensure that motor vehicles are not marketed or advertised in ways which might, however unintentionally, encourage inappropriate attitudes or lead to careless, inconsiderate or dangerous driving.”(57) Yet in North America, with more lax advertising standards, research has found substantive risky driving in vehicle advertisements.(58) As their studies did not directly assess the effects of advertisements on driving behavior, Shin et al. concluded that “further investigation into the influence of driving behavior, as portrayed in automobile commercials, on consumer-driving behavior or attitudes is warranted” (p. 324). Studies on the causal relationship between risk-glorifying advertisements and increased risk-taking driving inclinations could provide legislators with information by which to pressure motor vehicle manufacturers and the advertising industry to develop stronger vehicle advertisement rules, as has been introduced in Australia, New Zealand, and the European Union. Similarly, the educational information and rating systems for video games could be improved and expanded within the context of these findings. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. REFERENCES 1. Harvey A, Towner E, Peden M, Soori H, Bartolomeos K. Injury prevention and the attainment of child and adolescent health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2009; 87:325–404. 2. Ben-Zur H, Zeidner M. Threat to life and risk-taking behaviors: A review of empirical findings and explanatory models. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2009; 13:109–128. 3. Brown J, Witherspoon E. The mass media and American adolescents‘ health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2002; 31:153– 170. 4. Escobar-Chaves SL, Anderson CA. Media and risky behaviors. Future of Children, 2008; 18:147–180. 5. Shelov S, Baron M. Sexuality, contraception, and the media. Pediatrics, 1995; 95:298–300. 6. Strasburger VC. Children, adolescents, and television—1989: II. The role of pediatricians. Pediatrics, 1989; 83:446–448. 7. Young CC. Extreme sports and medical coverage. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 2002; 1:306–311. 8. Blows S, Ameratunga S, Ivers, RQ, Kai Lo S, Norton R. Risky driving habits and motor vehicle driver injury. Accident, Analysis and Prevention, 2005; 37:619–624. 9. Blincoe L, Seay A, Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Romano E, Luchter S, Spicer R. The economic impact of motor vehicle crashes 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, Rep. No. DOT HS 809 446, 2002. 10. Glaeske G, Schicktanz C, Jahnsen K. Auswertungsergebnisse der GEK-Arzneimitteldaten aus den Jahren 2007 bis 2008 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. [GEK pharmaceuticals report 2009. Results of the pharmaceutical data 2007 to 2008]. Bremen, Schwäbisch Gmünd: Schreiftenreihe zur Gesundheitsanalyse, Band 68, GEKArzneimittel-Report 2009. Lampert T. Tabakkonsum und Passivrauchbelastung von Jugendlichen [Smoking and passive smoking exposure in young people—Results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KIGGS).]. Deutsches Aerzteblatt, 2008; 105:265–271. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva. UNAIDS, 2008. Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2004; 36:6–10. Hurley C, Kiragu AW, Peltier GL. The media and “copycat” burn injuries: 21st century impediments to burn prevention. Journal of Trauma, 2006; 60:1382. Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, Rothstein HR, Saleem M. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries. Psychological Bulletin, 2010; 136:151–173. Fischer P, Guter S, Frey D. Exposure to risk-related media: The effects of media stimuli with positively framed risk-related content on risk-related thoughts, inclination to take risks, and actual risk-taking behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 2008; 30:230–240. Fischer P, Kubitzki J, Guter S, Frey, D. Virtual driving and risk taking: Do racing games increase risk taking cognitions, affect, and behaviors? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 2007; 13:22–31. Fischer P, Greitemeyer T, Morton T, Kastenmüller A, Postmes T, Frey D, Kubitzki J, Odenwälder J. The impact of video racing games on risk-taking in road traffic: Underlying psychological processes and real-life relevance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2009; 35:1395–1409. Vingilis E, Smart RG. Street racing: A neglected research area? Traffic Injury Prevention, 2009; 10:148–156. Beullens K, Roe K, Van Den Bulck J. Video games and adolescents’ intentions to take risks in traffic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2008; 43:87–90. Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Smoking in the movies increases adolescent smoking: A review. Pediatrics, 2005; 111:1516– 1528. Gutschoven K, Van Den Bulck J. Television viewing and age at smoking initiation: Does a relationship exist between higher levels of television viewing and earlier onset of smoking? Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 2005; 7:381–385. Schooler C, Feighery E, Flora JA. Seventh graders’ selfreported exposure to cigarette marketing and its relationship to their smoking behavior. American Journal of Public Health, 1996; 86:1216–1221. Unger JB, Schuster D, Zogg J, Dent CW, Stacy AW. Alcohol advertising exposure and adolescent alcohol use: A comparison of exposure measures. Addiction Research and Theory, 2003; 11: 177–193. Pardun CJ, Engle KL, Brown JD. Linking exposure to outcomes: Early adolescents’ consumption of sexual content in six media. Mass Communication and Society, 2005; 8:75– 91. Kubitzki J. Zur Problematik von Video-Rennspielen [The problem of video racing games]. Zeitschrift fuer Verkehrssicherheit, 2005; 3:135–138. Kubitzki J. Video Driving Games and Traffic Safety—A Matter of Concern? Results from a Questionnaire Survey in 13– 17-Year-old Male Adolescents. Paper presented at the International Congress of Applied Psychology, Athens, Greece, 2006. Risk-Taking and the Media 28. Wills TA, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Stoolmiller M. Movie exposure to alcohol cues and adolescent alcohol problems: A longitudinal analysis in a national sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 2009; 23:23–35. 29. Collins R, Ellickson P, McCaffrey D, Hambarsoomians K. Early adolescent exposure to alcohol advertising and its relationship to underage drinking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2007; 40:527–534. 30. Connolly GM, Casswell S, Zhang J, Silva P. Alcohol in the mass media and drinking by adolescents: A longitudinal study. Addiction, 1994; 89:1255–1263. 31. Ellickson PL, Collins RL, Hambarsoomians K, McCaffrey DF. Does alcohol advertising promote adolescent drinking? Results from a longitudinal assessment. Addiction, 2005; 100:235–246. 32. Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stollmiller M, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Movie smoking exposure and smoking onset: A longitudinal study of mediation processes in a representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 2008; 22:269–277. 33. Titus-Ernstoff L, Dalton MA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, Beach ML. Longitudinal study of viewing smoking in movies and initiation of smoking by children. Pediatrics, 2008; 121:15–21. 34. Collins RL, Elliott, MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Kunkel D, Hunter SB, Miu, A. Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics, 2004; 114:280– 289. 35. Hines D, Saris RN, Throckmorton-Belzer L. Cigarette smoking in popular films: Does it increase viewers’ likelihood to smoke? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 2000; 30:2246– 2269. 36. Potts R, Doppler M, Hernandez M. Effects of television content on physical risk-taking in children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 1994; 58:321–331. 37. Kulick AD, Rosenberg H. Influence of positive and negative film portrayals of drinking on older adolescents’ alcohol outcome expectancies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 2001; 31:1492–1499. 38. Vorderer P, Klimmt C. Rennspiele am Computer: Implikationen für die Verkehrssicherheitsarbeit. Zum Einfluss von Computerspielen mit Fahrzeugbezug auf das Fahrverhalten junger Fahrer (Schriftenreihe der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Reihe “Mensch und Sicherheit”, M181). [Computer Racing Games: Implications for Traffic Safety]. Bremerhaven: Verlag für Neue Wissenschaft, 2006. 39. Fischer P, Greitemeyer T, Kastenmüler A, Vogrincic C, Sauer A. The effects of risk-glorifying media exposure on riskpositive cognitions, emotions, and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, in press. 40. Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Violent video games and hostile expectations: A test of the general aggression model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2002; 28:1679–1686. 41. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1996. 42. Huesmann LR. Psychological processes promoting the relation between exposure to media violence and aggressive be- 705 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. havior by the viewer. Journal of Social Issues, 1986; 42:125– 139. Dodge KA, Crick NR. Social information-processing bases of aggressive behavior in children. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1990; 16:8–22. Zillmann D. Transfer of excitation in emotional behavior. Pp. 215–240 in Cacioppo JT, Petty RE (eds). Social Psychophysiology: A sourcebook. New York: Guilford Press, 1983. Berkowitz L. Some effects of thoughts on anti- and prosocial influences of media events: A cognitive-neoassociation analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 1984; 95:410–427. Carnagey NL, Anderson CA. The effects of reward and punishment in violent video games on aggressive affect, cognition and behavior. Psychological Science, 2005; 16:882– 889. Buckley KE, Anderson CA. A theoretical model of the effects and consequences of playing video games. Pp. 363–378 in Vorderer P, Bryant J (eds). Playing Video Games: Motives, Responses, and Consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2006. Greitemeyer T. Effects of songs with prosocial lyrics on prosocial thoughts, affect, and behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2009; 45:186–190. Greitemeyer T. Effects of songs with prosocial lyrics on prosocial behavior: Further evidence and a mediating mechanism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2009; 35:1500– 1511. Greitemeyer T, Osswald S. Prosocial video games reduce aggressive cognitions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2009; 45:896–900. Greitemeyer T. Exposure to music with prosocial lyrics reduces aggression: First evidence and test of the underlying mechanism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, In press. Greitemeyer T, Osswald S. Effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2010; 98:211–221. Greitemeyer T, Osswald S, Brauer M. Playing prosocial video games increases empathy and decreases schadenfreude. Emotion, In press. Gentile DA, Gentile RJ. Violent video games as exemplary teachers: A conceptual analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 2008; 9:127–141. Anderson CA, Gentile DA, Buckley KE. Violent Video Game Effect on Children and Adolescents. Theory, Research and Public Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement media violence. 2009. Retrieved from www.pediatrics.org/cgi/ doi/10.1542/peds.2009-2146; doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2146, Accessed November 17, 2010. The European Advertising Standard Alliance. Issue Brief— Car Advertising. 2008. Accessed on May 20, 2009 from http:// www.easa-alliance.org/page.aspx/353. Shin PC, Hallett D, Chipman M, Tator C, Granton JT. Unsafe driving in North American automobile commercials. Journal of Public Health, 2005; 27:318–325. Copyright of Risk Analysis: An International Journal is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.