Market economics in earthquake affected regions

Feeling the Aftershocks- Market economics in earthquake affected regions

Erum Haider

Michael Sequeira

A point in time has come where people affected by the October 8 th earthquake can no longer be thought of as helpless victims, or passive recipients. The millions of people who are now relying on their own resources to rebuild their lives have been gradually erased from the public eye. They are ‘less vulnerable’ citizens who, by virtue of having access to markets, are somewhat lower on the policy maker’s priority list. The decreased dependence on charity does not restore lives to normal; self-reliance for many of the affected households comes with its own set of problems.

According to a survey conducted this January by students of the Lahore University of

Management Sciences in villages and camps in Muzaffarabad and Mansehra-Balakot, some 75% of the 350 households in various relief camps and settlements rely on markets for food, medicine, tin sheeting, blankets and clothes.

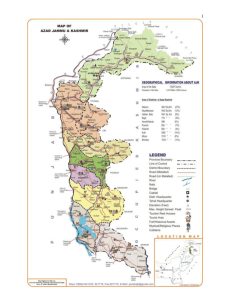

Dhana is a one such settlement of about 50 households, located in Neelum Valley,

Muzaffarabad, at an altitude of 3000 m, some 5 km from the main road. On a good day, the nearest market is a two-hour walk down. (Landslides and broken roads make grocery shopping a day’s journey). Yet every household makes this difficult but necessary trip at least twice a week, even in mid-winter. (Each household received fifty kilos of atta from the World Food Program, which was consumed within the first few weeks of the earthquake, and little aid has been received by this part of the valley since then). On average, people reported that they spent 60% of their compensation just providing their families with three meals a day. Given that most families lost a steady source of income and that there has been immense asset loss, this puts many people in an extremely vulnerable situation.

In Muzaffarabad city, atta prices in January had gone up 9.6% since the earthquake.

Prices for daals had increased by 10.5%; sugar by 13% and milk by 20%. In addition to that, transport and rent rates have skyrocketed, having increased by 100 and 167%, respectively.

In rural areas such as Patika in Neelum Valley, the increases are even starker. Atta prices were reported to have gone up by 30%, rice by 40%, lentils by 31% and vegetables by

130%. Transport costs increased by 900%.

Price hikes, especially in transport costs, are not unique to the AJK region. In Abbottabad and in the NWFP regions of Mansehra and Batagram rates had almost doubled, both for transport within and between districts. Variation does exist across the regions - in

Abbottabad and Mansehra, significant increases were noted only in the price of rice, sugar, and milk. In Batagram, however, daal and vegetables have also gone up by 20-

30%.

The facts point to an increased demand in the markets. Normally, people in villages were somewhat protected from fluctuations in market prices by their own agricultural stock.

While households did not rely on it for their income, it was an important source of food for animals and an emergency supply of food for the family. Throughout the earthquake affected regions, households are reported to have lost anywhere from 50 to 100% of their crop last year. According to respondents, the earthquake took place in the middle of the harvest season. The part of the crop that was recovered was destroyed in the cold for lack of storage facilities.

A simple calculation shows that the compensation received by families is going straight back into the pockets of the richer segments of society. Most of the produce consumed in

Muzaffarabad comes from mandis in Rawalpindi and Mansehra. Transportation is entirely controlled by private owners who are not only from the earthquake affected areas but also from outside the region, who have been setting extremely high rates since the earthquake. This also tends to explain why Mansehra and Abbottabad did not experience price increases in vegetables, because most of the goods are produced locally.

Property rates and rent present a similar story. Danish, who works for an NGO in

Muzaffarabad, reported the following:

“I used to pay 9000 rupees in rent for my apartment in Muzaffarabad. Since the earthquake, the plot next to mine is worth 25,000 rupees. My landlord now expects me to pay 24,000 rupees a month.”

When asked why prices of the neighboring plot had gone up, he replied “a foreign NGO came in and agreed to pay the owner whatever rent he demanded. Now no one is willing to rent out for less.”

Unfortunately, this is not the only case of international agencies distorting market prices.

A large number of local transporters have been hired by these agencies, usually at rates well exceeding what the common man can afford to pay. And this reality hits closer to home than we realize. In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, private groups and

NGOs paid transporters in Lahore, Rawalpindi, Karachi and NWFP extraordinary fares to get relief goods up to affected areas. Since then, the number of hired vehicles has decreased and prices have stabilized across the board - making things marginally, but not much better for the people. Transport prices could be the single largest reason for the huge increases in the price of food and other commodities in this region.

Given that people in these areas are already highly susceptible to localized market fluctuations, it is anyone’s guess how nationwide shocks such as the recent surge in sugar prices has affected their lives. Data coming out of these areas is seriously challenging the notion that households are still dependent on food aid from relief organizations - which is not to say that an increase in food aid is what is needed, or even desired. Most households are eager to become self-reliant, and hope that basic services such as transport and some kind of economic stability are provided for by the state. The livelihoods of these communities are being affected by price fluctuations, and this deserves serious attention. Such a realization might put pressure on foreign and local agencies to act responsibly when buying goods and renting transport, and to critically assess their impact on the people amongst whom they are living. It is in the government’s interest and ability to regulate prices and fares; at the very least, to monitor them on a regular basis. While it may be a positive sign that people are now less dependent on relief, the institution they are increasingly dependent on - the market - is far from stable.