SUNDAY WALKS WITH DAD

advertisement

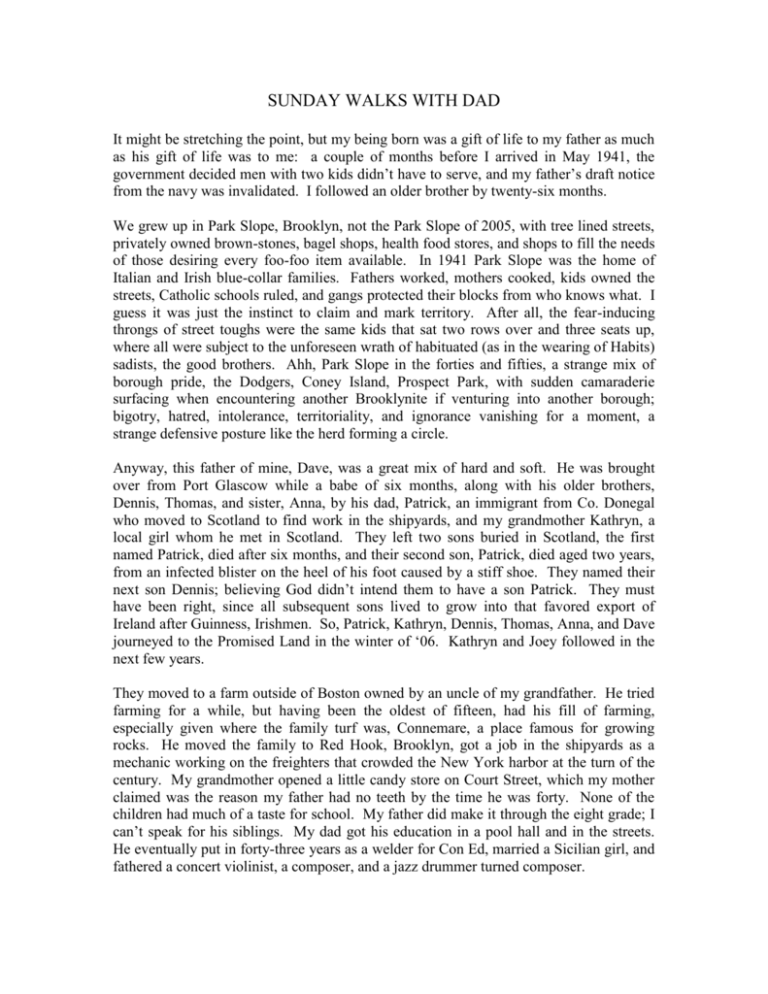

SUNDAY WALKS WITH DAD It might be stretching the point, but my being born was a gift of life to my father as much as his gift of life was to me: a couple of months before I arrived in May 1941, the government decided men with two kids didn’t have to serve, and my father’s draft notice from the navy was invalidated. I followed an older brother by twenty-six months. We grew up in Park Slope, Brooklyn, not the Park Slope of 2005, with tree lined streets, privately owned brown-stones, bagel shops, health food stores, and shops to fill the needs of those desiring every foo-foo item available. In 1941 Park Slope was the home of Italian and Irish blue-collar families. Fathers worked, mothers cooked, kids owned the streets, Catholic schools ruled, and gangs protected their blocks from who knows what. I guess it was just the instinct to claim and mark territory. After all, the fear-inducing throngs of street toughs were the same kids that sat two rows over and three seats up, where all were subject to the unforeseen wrath of habituated (as in the wearing of Habits) sadists, the good brothers. Ahh, Park Slope in the forties and fifties, a strange mix of borough pride, the Dodgers, Coney Island, Prospect Park, with sudden camaraderie surfacing when encountering another Brooklynite if venturing into another borough; bigotry, hatred, intolerance, territoriality, and ignorance vanishing for a moment, a strange defensive posture like the herd forming a circle. Anyway, this father of mine, Dave, was a great mix of hard and soft. He was brought over from Port Glascow while a babe of six months, along with his older brothers, Dennis, Thomas, and sister, Anna, by his dad, Patrick, an immigrant from Co. Donegal who moved to Scotland to find work in the shipyards, and my grandmother Kathryn, a local girl whom he met in Scotland. They left two sons buried in Scotland, the first named Patrick, died after six months, and their second son, Patrick, died aged two years, from an infected blister on the heel of his foot caused by a stiff shoe. They named their next son Dennis; believing God didn’t intend them to have a son Patrick. They must have been right, since all subsequent sons lived to grow into that favored export of Ireland after Guinness, Irishmen. So, Patrick, Kathryn, Dennis, Thomas, Anna, and Dave journeyed to the Promised Land in the winter of ‘06. Kathryn and Joey followed in the next few years. They moved to a farm outside of Boston owned by an uncle of my grandfather. He tried farming for a while, but having been the oldest of fifteen, had his fill of farming, especially given where the family turf was, Connemare, a place famous for growing rocks. He moved the family to Red Hook, Brooklyn, got a job in the shipyards as a mechanic working on the freighters that crowded the New York harbor at the turn of the century. My grandmother opened a little candy store on Court Street, which my mother claimed was the reason my father had no teeth by the time he was forty. None of the children had much of a taste for school. My father did make it through the eight grade; I can’t speak for his siblings. My dad got his education in a pool hall and in the streets. He eventually put in forty-three years as a welder for Con Ed, married a Sicilian girl, and fathered a concert violinist, a composer, and a jazz drummer turned composer. The times were raw and rough with hordes of immigrants pushing and shoving each other trying to climb to the top of the pile. Irish and Scots settled into the police and fire departments along with Con Edison, keeping order, putting fires out, and supplying the city with electric. Italians built stone walls, brick buildings, plied their carpentry, opened bakeries, butcher shops, vegetable stores, restaurants, taking a stand against all nonItalians, preaching family, precluding education, travel, or anything seen as a threat to the family, while the Jews sold yard goods, knishes, bagels, shoes, opened Kosher restaurants, or drove cabs, and cleverly saved money to assure higher education for their children, whose grandchildren are now the doctors my cousins visit when they get injured on the job. We didn’t have much but each other growing up in the forties. The war diverted everything to its effort. The miracle of childhood is that you think that the status-quo you perceive around you is as it should be, so while parents rage about scarcity, the children feel that all is perfect, arguing over who’s going to whip the powered food coloring into the margerine. My mother cooked great Italian meals, and my dad took my brother Peter and me all over Brooklyn on Sundays, and we had warm beds, and clean sheets. What more is there? This is a good time to explain why my older brother was named Peter, and not David, and how I ended up being the junior in the family. One day the dock foreman went over to my grandfather and said when he finished up what he was doing, he was to go over to such and such slip, where he’ll find a freighter that just got in from Cork, find the chief engineer’s cabin and tell him you’re there to look at the problem they were having with the engines. My grandfather knocked, the door opened and the two men stared at each other for a moment, then, as if on a signal, hugged violently, started balling like two kids, grandpa shouting, “Peter, Peter,” and Peter asking, “Is that you, Patty, is it you?” It was my grandfather’s kid brother. They hadn’t seen each other for many years. This was but one incident I recall that would invalidate my mother’s accusation that the Irish were cold and not close like Italians –Il famiglia! Peter was taken home to his brother’s house to meet his nieces and nephews, and as the years passed, was a frequent visitor whenever his ship landed in New York. When my older brother was born, my father named his first son after his sea-faring uncle. While I was growing up my mother complained that we didn’t have this or that, and nagged my dad incessantly. He was like an obedient bull, working, never complaining except about my mother’s dissatisfaction with life. He couldn’t understand why food and a place to live wasn’t enough, while she couldn’t understand his indifference to life on the lower rungs of the ladder. He liked the fights, baseball, and singing. She liked concerts, fine clothes, and opera. It was bound to splinter, and did, after twenty-two years. Meanwhile, while we were still a family, he gave his forty a week to Con Ed, but also worked either as a long shore man, or pin setter in a bowling alley, or as a bookey for the guys at the power-house, as they called it. Nothing was ever enough. She broke his balls every day. Funny thing was, he was always singing, laughing, a friend to all, while she was bitter, angry, and contemptuous of those who shared our neighborhood, never venturing beyond the family in search of friendship. Sundays were always the same: church, early afternoon meal of pasta and meatballs, or sausage, or bracioli, roast stuffed chicken, or roast beef, or Virginia ham, potatoes, salad. Mom loved to cook and eating was one of the few activities that gave her pleasure aside from listening to classical music. After the meal, my father would take Peter and I for the Sunday outing. We would walk and walk and walk, and walk some more. Subways were a nickel, but his Irish/Scottish DNA demanded we walk. Gone were the gentle hills with grazing sheep, dogs running around the flock, clouds bringing the quick-then-it’sover rain, the moors, the bogs, the mountain waterfalls, all replaced with pavement, tenements, tall buildings, bridges, crowded streets, rivers, cars, subways, the masses racing in all directions. Still, we walked as if we were crossing Fitzgerald’s meadow, not a care in the world, singing You Take The High Road, over and over again. Our destination was usually the Staten Island ferry. There were two in those days: one from 69th. St., Brooklyn, the other from the Battery in lower Manhattan. We would walk across the Brooklyn Bridge to catch the Manhattan ferry. It was thrilling to stand at the rear of the ferry as it pulled out, the lower skyline and bridges receding as we turned right along side of Governor’s Island, and entered the bustling harbor making our way between giant ships at anchor, and harbor tugs pulling barges of coal, or tires, or garbage. The air was suddenly clean, smelling of salt, renewing, while we fantasized about this ship or that, some new, some rusty old tubs ready to sink. If we were lucky, a carrier, destroyer, or battleship would be at anchor. We could feel the might and power of the silent guns, imagining the terrible fury that must have been released before sailing to the harbor. The Statue of Liberty, the war ships, the ships at anchor, the busy harbor, the whistles, planes passing over on their way to La Guardia, always raised the hair on my arms. We were Americans: free, proud, fierce, ambitious, hard working, honest and good. The cynicism of the coming decades hadn’t arrived yet. Some Sundays my father, while still in bed, would send me down to the candy store to fetch the Daily News. He’d look up the incoming ship schedule, and if there were an ocean liner coming in, he’d tell me to lie still in bed. We would listen to the harbor whistles until we’d hear the very deep-throated call of the arriving liner. He told me that ship whistles were sized according to the size of the boat. The little harbor crafts had tiny whistles, with the size increasing as the ship’s size increased. I guess if you took all the whistles from all the different sized boats and arranged them in an order from low to high, and put them in a church choir loft, you could make a pretty good organ with a little tuning here and there. I’m sure J. S. Bach would be amused and play the hell out of it. No doubt he’d have written the Harbor Cantata. (A secular work.) As the ferry would dock in Staten Island, my father would usher us into a stall in the men’s room. We’d quietly wait there until the ferry pulled our again, saving the 15 cents it would have cost the three of us to get off and back on. Once a deck hand checked to see if anyone was in the toilet, and discovered us. My brother and I crapped ourselves, but dad said, “Ah, I’m just taking my boys back and forth a few times.” The deck hand said, “Just stay there to the boat pulls out, and have a fine day.” (The Irish infiltrated the Port Authority as well.) To which my father replied with a wink, “Thanks, Johnny.” As I got older and we explored every inch of the city, I began to notice my father always addressed the men we encountered by name, including deck hands on ferries, change clerks in the subways, counter men in candy stores when we stopped for a Coke and a bar of Hershey’s, police, or just strangers. Of course he didn’t know anyone’s name. He always had ready three names that would be used without hesitation, depending on the situation and how he responded to the vibe of the person he was interacting with. Role, station, uniform meant nothing to him. He saw everyone as a person. Johnny was kept for friendly encounters, like the one with the deck hand on the ferry. Willy was used in situations that required him to speak up, not wanting to be hostile, but not wanting to be too familiar. For instance, if we were trying to sit down on a subway seat and someone had their foot up on the side of the seat we were trying to use, he’d instantly say, “C’mon Willy, put your foot down.” It would come out with such nonchalance, and authority, that that foot would be off the seat in a blink, usually followed by the foot’s body looking up with complete surprise realizing they had just responded to an order given by a total stranger. McGirk was used as a more formal address when he wanted to show respect, but make his point. I heard him use McGirk once when we sat at the counter of a candy store and he ordered three Cokes. In those days, when you ordered a Coke at the counter, the clerk squirted syrup in a glass and filled it with seltzer water. This one time I remember, the Coke was barely flavored. My father took a sip and immediately said, “Jesus, McGirk, you own the store? Put some syrup in the glass, it aint comin’ out of your pay.” My brother and I were always embarrassed and wished we could hide when my father spoke to strangers. As we got on our way, we’d ask dad if it was necessary for him to speak to everyone, to which he replied, “If you don’t speak up for yourself, no one else will.” My father’s long dead now, but I sure appreciate the ease with which I now go about New York City, not seeing a uniform as a barrier to the person wearing it, talking to anyone who requires dealing with, never feeling intimidated by another’s bad mood, and smiling as I walk, singing another verse of You Take The High Road. David McHugh 7 May 2005 Winston-Salem, NC