Greco-Roman Antiquity in 19th century Bohemia

advertisement

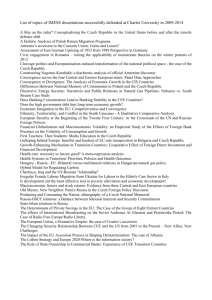

Greco-Roman Antiquity, Europe and 19th century Bohemia. Jan Bažant The foyer of the National Theatre in Prague is the holy of holies of the Czech national renaissance (fig. 1) and its cult statue is called Music. The leading Czech master of that time, Josef Myslbek, started to work on it in 1872 and the final version comes from the years 1907-1912 (fig. 2). Every Czech would tell you that it is typically Czech, while strangers would tell you that this classicistic statue is typically European. The ancient Greek and Roman models of the Music statue are evident, its proportions being probably adapted from the Esquiline Venus, as its photograph with Myslbek’s measurements seems to indicate (fig. 3). Besides, Music can be compared with, say, Emil Wolff’s statue of 1855 or with any other variation on the type of ancient Greek Venus, which were created throughout the 19th century (fig. 4)1. The difference is, of course, in theme and in placement, the Berlin statue represents a trivial action, the ancient Roman woman is putting off her earring, and it was created as a mere decoration of the Sansoussi Park. Classicistic building of the National Theatre of 1865-1883, in which Music is enshrined, is also perceived as a peculiarly Czech and again, it is difficult to say why (fig. 5). The House of Artists constructed not far from the National Theatre in 1874-1885, arouses no emotions whatsoever in Czechs, which a stranger might find surprising, because both these buildings were designed by Josef Zítek and realised by Josef Schulz (fig. 6). In what is the difference? It is definitely not in forms, but in intentions - the National Theatre was constructed for Czechs and that is why Czechs called it “Our Chapel”, “the Golden House” or “the Temple of Rebirth”2. The House of Artists was constructed for all inhabitants of Prague, Czechs and Germans alike. It was a concert hall and gallery, in which the language did not play central role. Myslbek’s Music and Zítek’s National Theatre are typical products of the 19th century national classicism, which seems to be a contradiction in terms, but it is not. In 19th century Europe, nationalists had two antithetical aims - they wanted their specificity to be respected and at the same time, they wanted to be perceived as men of the world. In 1848, the so-called old Czech dress was invented (fig. 7)3, but after the revolution was crushed, it was strictly forbidden by Austrian authorities and in streets of Prague Slav hats were frequent objects of police persecution. Austrians did not want Czechs to be known by their dress, but even the protagonists of the Czech national renaissance, which insisted on Slav dress in defiance of police restrictions, simultaneously took care to be dressed according to the last European fashion. The writer Jan Neruda was particularly famous for his excessive concern with Western dress and appearance (fig. 8)4, nevertheless, when he went to Paris, which was his first visit to Western Europe, he sported fantastic Slav costume (fig. 9)5. Neruda visited Paris in 1863, when the Austrian oppression started to ease up in the Czech lands and in 1881, the above mentioned National Theatre in Prague was opened. In the official publication prepared for this occasion, the first director of National Theatre, F. A. Schubert, characterizes it as “castle and palace of art, of our art”. The opening pages of the book, from which these words were quoted, contain a telling illustration by Adolf Liebscher. We see neither a castle, nor a palace, but a group of common people, moreover coming from distant past. They are mythical Czechs characterised by an archaically looking log cabin and prehistoric dress and they are looking across millennia to the silhouette of the National Theatre, which emerges from the fog on the far right (fig. 10). The works of art of this kind served as a confirmation that Czechs are embedded in something primeval, that they form a community embracing not only the living but also the dead. In Liebscher’s illustration, the Czech history is telescoped into its beginning in prehistory and its climax in 1881, which is exemplified by the characteristic silhouette of the National Theatre (fig. 11)6. The beginning is also represented with 19th century accuracy, the genuineness of mythical Czechs being guaranteed by their dress reconstructed with the help of archaeological finds (fig. 12). The head of the Old Czech family wears on his neck a variation on the famous fastener with pendants from Želenice, which Liebscher knew either from its publication in the first Czech archaeological journal published in 1855 (fig. 13)7 or from a visit in the National museum in Prague opened five years earlier (fig. 14). 1 Czech nation identified its heritage with the common folk and mythical past - the commoner and older the ancestors of contemporary Czechs were the more authentic they were thought to be. As is to be expected in 19th century, these humble ancestors of modern Czechs were glorified by opera in pompous Wagnerian style. On 11 June 1881, the National theatre was ceremonially opened by Smetana’s opera Libuše, in which mythical Czechs appeared on the stage (fig. 15)8. It is to be noted, that the variation on the Želenice dress fastener appears also in the recent staging, even though we know that Czech ancestors never wore it, for it comes from Late Hallstatt period, almost thousand years before first Slaves arrived to Bohemia (fig. 16). The fact that even today the mythical Czechs of the 19th century national renaissance still live on the stage of the National theatre in Prague demonstrates the enormous impact of this nationalist movement on modern Czech culture. The 1881 premiere of Libuše was actually an inversion of the situation represented on Liebsher’s illustration - mythical Czechs are not longingly looking at the National theatre from their distant era, but they were brought on its stage, from which they addressed their descendants. The opera is named after Libuše, the mythic Queen of Bohemia, but its main hero is, of course, Czech nation - when there is a dispute, Libuše recommends that the people should decide and the opera ends with reconciliation to the delight of all. The common Czechs in patriotic operas, needless to say, do not speak in a village dialect, but in the standard literary language, the propagation of which was the main idea behind the National Theatre. The Czech national renaissance of the second half of the 19th century is firmly rooted in the Enlightenment of the 18th century. It inherited from this movement its dilemma of nationalism and cosmopolitanism, as well as its obsession with beginnings and the common folk, its zealous promotion of the standard literary language and, last but not least, the adulation of the classical canon in art and architecture. Czech patriotic artists of the later 19th century took up the line of classical revivalism, which originated in Western Europe of the second half of the 18th century, and presented it as the Czech national art. The continuity of classicistic taste in Czech lands was demonstrated for instance in the recent survey of the art of tombs in 1780-1830. It is surprising to find “genius of death” also in an out-of-the-way cemetery under the Krkonoše Mountains, where the miller from Lhota village, Antonín Jiřička felt it necessary in 1823 to demonstrate his admiration for the heritage of ancient Greeks and Romans (fig. 17). We must not forget that in Prague the Academy of fine arts was founded already in 1799. In it, students were forced to copy plaster casts of ancient statues and from 1869, they also listened to lectures on the history of art in which ancient Greek and Roman creations were presented as the inimitable ideal. The discontinuity of the Czech culture in 18th and 19th century was an influential thesis, with the help of which Czech nationalist movement stressed achievements of the Czech visual arts by taking recourse to the traditional rhetoric triad of the “golden age - decline - rebirth”. Czech art and architecture of the second half of the 19th century was presented as a turning point, degree zero in which the visual arts were “born again” and classical canon was reinstalled after the “dark age”. This point is explicitly stated in the ceiling painting of the foyer of the National Theatre in Prague, in František Ženíšek’s triptych called the “Three ages of the Czech lands”. In the centre, there is the allegory of the Golden age of art (fig. 18), which combines Greco-Roman traits with that of Czech prehistory. “The Decline of art” (fig. 19) flanks it on the left and “The Renaissance of art” (fig. 20) on the right, in which the building of the National Theatre building is presented as the climax of this “rebirth”. The National Theatre in Prague was constructed during a heavy shower of stone theatres, which poured down over Central Europe between 1870-1914. In almost every larger city, it left theatre buildings evoking classical antiquity, this inspiration being as a rule stronger, the greater were the ambitions of the builder. The construction of these theatres was often motivated by nationalistic and local-patriotic feelings and in the National Theatre in Prague, this extra-theatrical function was very pronounced. The National Theatre in Prague was presented as a manifestation of the unity of the Czech people, whose contributions supposedly made up the whole construction budget. It was simultaneously also presented as a demonstration of the high level of Czech engineering, architecture, sculpture, painting and decorative arts. 2 In contrast to many other Central European metropolises, Prague was able to boast a tradition of classical architecture going back as far as the 16th century, and the Czech press did not fail to remember this local classical tradition. We can read that the National Theatre was built: „entirely in the local style, the style which was transmitted from the land of arts, namely Italy, to the local territory, receptive for anything beautiful. This style is, in fact, nothing but a resurrection or renaissance of the building art of ancient Greeks and Romans, who are, and forever will be, a source of all beauty in architecture.“9 The National Theatre was to evoke not only classical antiquity and Renaissance Italy, but also the Czech buildings of past centuries, its roof (fig. 21) being interpreted as an echo of the Belvedere, which emperor Ferdinand I constructed at Prague Castle in 1537-1563 (fig. 22). The neo-Renaissance style was proclaimed as an attribute of Czech national revival and it is instructive to compare the National theatre in Prague with the theatre in Karlovy Vary, where Czechs were the truly insignificant minority. The tendency to stress the German presence in the western borderland of Bohemia steadily increased during the later nineteenth century. It kept pace with the Czech national revival and after the unification of Germany in 1871, this tendency gained momentum. The Karlovy Vary theatre by Viennese architects Fellner and Helmer was opened in 1884, only one year after the definitive opening of the National Theatre in Prague (fig. 23). It was, no doubt deliberately, in a different code and imported the newest trend from Vienna - the neo-Baroque style with direct quotations from Viennese architecture of the first half of the eighteenth century. This is not to say that Karlovy Vary perceived the neo-Renaissance as specifically Czech architectural style. At the end of the nineteenth century, the neo-Renaissance was not definitively out of style in Vienna nor, consequently, in Karlovy Vary. The decade after their neo-Baroque theatre, in 1895, the Fellner and Helmer studio built the monumental Imperial Spa in Karlovy Vary, which they designed in a sober neo-Renaissance style quite similar to that of National Theatre in Prague (fig. 24). In the time the National theatre in Prague was designed and constructed, that is in 1865-1883, the Czech half of Prague considered baroque style as decadent and specifically Austrian. Consequently, the neoRenaissance architecture of the National Theatre is implicitly criticising the neo-Baroque, and by its refusal, it refuses also the German language. The National Theatre in Prague had two functions – through this building Czechs wanted to enter into Europe and, at the same time, to isolate themselves from their Austrian German speaking compatriots. Otakar Hostinský, from 1877 the professor of the history of art at the Academy of fine arts in Prague, expressed it very clearly: „for us there is no and there should be no German theatre, our Czech National Theatre must fully meet your requirements.“10 To this the rhetoric of the National Theatre must respond - it had to be either commonly European or specifically Czech. According to Hostinský, architecture could be “European” because it is determined by its function and material, but sculpture and above all painting must demonstrate national traits. „A sculptor and a painter,” stresses Hostinský, “must respect real forms of external objects, but in the hard stone or colour surface representing the human face, they can imprint spiritual life and in this way also national traits.“11 The artists in the service of the Czech national renaissance were encouraged to adapt the classical models to serve their specific needs. “Modern sculpture,” writes aesthetician Otakar Hostinský, “forgets that even though classical antiquity is the true school of sculpture, an artist cannot remain a pupil forever, but must come out of the school age and enter into life. Modern sculpture loves classical subjects, but in doing this, lacks an independent creation of ideals … while in the field of national myths and legends it probably could find new, original ideals, and in this way it could truly achieve something in arts.“12 In the National Theatre, however, sculptures and paintings evoked in a general way Czech prehistory without illustrating individual mythical stories, a typical example being the painting “Myth” by Mikoláš Aleš and František Ženíšek (fig. 25). Nevertheless, in this way, the roots of the Czech national character were located in the very distant past, which gave the whole movement legitimacy. In the National Theatre, it was possible to combine the timeless classical architectural language with themes, which were also situated outside historical time. A common denominator of the architecture and its decoration was the fact that they were both deliberately singled out of immediately preceding history. The National Theatre is not presented as a part of an unbroken evolutionary line, but as an expression and monument of the rebirth of the Czech nation, which reversed the course of history 3 leading in the opposite direction, to its total destruction.13 Reinstallation of mythical past became a promise of the future. To this future pointed the curtain of the National theatre. Its stage is in classical style, but under the tympanum depicting figures from classical mythology there was a Czech inscription “NÁROD SOBĚ” (Nation to itself), which was upgraded as a state symbol by its position between the Czech royal crown and the emblems of the historical Czech lands, Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia (fig. 26). The content of the inscription did not correspond with its classicizing frame, but instead with the painted curtain under it. In 1883, Vojtěch Hynais on this curtain depicted not only representatives of the Czech nation collecting money for their National Theatre, but also artists and artisans, who erected and decorated it (fig. 27). Also represented are Czechs working on Czech repertoires for their new theatre and Czechs preparing to perform them. The curtain did not look, consequently, backwards, but heralded the magnificent future of the resurrected Czech nation, into which the audience will enter, through the proscenium arch crowned by the tympanum. According to Hostinský, in sculpture and painting, the Czech character had to be shown above all in the faces of the represented figures, these faces had to have “Slav,” ostentatiously un-German features. That was the reason, why the management of the National Theatre at first refused to accept the curtain of Hynais. His Czechs did not have Czech features, but rather resembled Hynais’s French models. According to the Czech patriots, Hynais mixed the European and Czech tendency in a way, which could not be permitted. Hynais, however, pushed through his conception in which the Czech nation was celebrated by a representation of Czechs with nationally neutral physiognomies. Hynais’ Czechs were not represented in their present situation, which left much to be desired, but in a future state, when their national character will be fully recognized and, consequently, when specifically Czech physiognomies will not be necessary any more in Czech visual art. Consequently, after initial hesitation, Czechs took Hynais’ curtain to their hearts. In the second half of the 19th century, artists who created the Czech art, were as a rule trained abroad, mostly in Munich and their view of life was much more cosmopolitan than that of their compatriots. There were also very important impulses coming from the Prague German community. The very first professor of classical archaeology in the Czech lands was the German Otto Benndorf (1830-1907), and though he only worked in Prague for a short time (1872-1877), it was probably the time of the greatest and most lasting influence of this branch of science on Czech culture. Benndorf came to Prague after having worked briefly at the universities of Zurich and Munich as, even then, an outstanding expert on Greek art. During his stay in Prague, Benndorf concentrated on giving lectures, which greatly influenced a number of Prague intellectuals and artists, and his effort to enable the people of Prague to get to know classical art from their own experience brought great response. In 1873, the university collection of two hundred plaster casts of classical statues was opened to the public and thanks to Benndorf also the Prague university collection of Greek and Roman antiquities came into being. The fact that it was possible to study ancient Greek and Roman art in Prague was of fundamental importance due to its creative reception, especially in Czech sculpture. Benndorf’s lectures and his collection of plaster casts influenced the founder of Czech modern sculpture, Josef Myslbek. His Devotion of 1880-1884 (fig. 28) was modelled on Sophocles of Lateran (fig. 29), his Christ of 1885 (fig. 30) follows the torso of hanging Marsyas (fig. 31). However, there was also Czech classical archaeology and in the national renaissance, the culture of ancient Greeks and Romans was appropriated not only by architects and by artists, but also by scholars, which was also heritage of the Enlightenment. In Western Europe, the close link between classical archaeology and contemporary culture was typical for the 18th century14, in the Czech lands, this situation characterizes the second half of the 19th century. The first Czech classical archaeologist Miroslav Tyrš (1832-1884) was a very active nationalist and founder of the Czech gymnastic movement “Sokol”(falcon). This late echo of German “Turnbewegung” was presented by Tyrš as a revival of the ancient Greek idea of physical training integrated in the cultural, social and political life of the entire community (fig. 32). Tyrš had started his career by publishing articles on classical art in popular magazines and giving lectures on this theme in the Arts Club in Prague, which is typical for the close links between classical archaeology and cultural life in the Czech lands at the last third of 19th and the 4 beginning of 20th century. In this period, the popularization of the then modern knowledge on classical art and architecture in the form of Czech lectures, articles in magazines and monographs, reached its absolute peak. Tyrš found his first place at the Prague polytechnic founded in 1863. In Austro-Hungary the polytechnics and academies were another centre of the study of classical art. Students of architecture in particular were thoroughly taught about ancient Greek and Roman buildings. Their studies were completed by a study tour in Italy, during which the beginner architects could choose from the vast quantity of all kinds of ancient monuments those, which best corresponded to their artistic aims. These tours were of basic significance for the origin of neoclassical buildings of what was known as the Czech neo-renaissance. In 1883, Tyrš asked for the chair of classical archaeology in the Czech branch of the Prague University divided in the previous year, saying that he would also teach at the so-far-unoccupied chair of history of art, however, he was appointed professor of history of art. Tyrš understood classical archaeology as an indivisible part of European cultural history and for the long-delayed opening of his career as a university professor, he chose, certainly after careful consideration, a lecture on oriental art, in which he defended the then unusual theory, only generally accepted today, on the close association between oriental and ancient Greek art. Also Tyrš’s main scientific work, devoted to the well-known group statue of Laocoon and his sons, argued the unbroken continuity of the history of European art. The work was published in 1872 in Czech (fig. 33), and in 1882, after thorough revision, he submitted the German version as his thesis for his higher doctorate. In the European rediscovery of classical antiquity, the statue of Laocoon occupied the central position and the painting of 1773 by Hubert Robert presents its discovery on 14 July 1506 as a mystic revelation (fig. 34)15. In Tyrš’s day the statue of Laocoon was a standing problem, and it was a matter of pride for him, as he wrote at the beginning of his book, that the first work of Czech classical archaeology should show its originality and maturity on a theme that German science did not know how to deal with16. The provocative central idea - that the statue came from Roman times - was founded on his conviction that Roman art should not be underestimated. On the contrary, it had to be assumed that outstanding works originated in that epoch too, which are an authentic expression of the spirit of their time. Tyrš’s defence of Roman Laocoon was a defence of art, which is both derivative and original. Since precisely this was the situation of Czech art of Tyrš’s time, it is probable that he wanted to legitimize it with the help of the most famous work of ancient art. In a similar way to ancient Roman art, Czech art tried to use forms and themes conforming to the universally accepted canon to propagate specifically Czech ideology. Be it as it may, in Tyrš’s time the idea of the Roman origin of Laocoon was unique. Franz Wickhoff only put forward a defence of Roman art in 1895, and an archaeological discovery in the Sperlonga cave, which confirmed that the statue of Laocoon really does come from the period of Tiberius, was made quite recently17. With his attempt to grasp both the continuity of the development of art and the unique nature of its individual epochs, especially those the originality of which was denied, Tyrš anticipated Alois Riegel and the Vienna school of the history of art. However, as a result of circumstances, his health problems and the wide variety of his interests, Tyrš was never able to give his original ideas a form that would influence Czech art or the trends of European classical archaeology. Around 1900, the spell that classical culture cast on patriotic Czechs dried out. Classical antiquity ceased to be considered as “the true school of sculpture,” and the contribution of Bohuslav Schnirch, the chief classicist sculptor working for the National Theatre, was openly ridiculed, especially his tympanon above the proscenium arch (fig. 35, plaster model in the National gallery). „Even his “Čechia” in the centre of his tympanum is some woman from the classical south in the middle of the Dionysos revelling. “18 The author of the above quoted words, K.B.Mádl, at that time professor of history of art at the High school of decorative arts in Prague, asks: „who would raise his eyes in exaltation towards the tympanum?“ In addition, he himself gives the answer: “foreign, learned concepts and images of bygone nations, which are distant from us. How could they inflame an artistic mind to original creation?“19 5 At the beginning of the 20th century, Myslbek creates the final version of the statue of Music for the foyer of the National Theatre, on which he was working from 1872 (fig. 36). Music’s dependence on classical models is obvious, but it was never ridiculed and the reasons are self-evident. Myslbek’s statues differ from that of Schnirch by small but enormously important details. The theme of a girl pressing a lyre to her heart and kissing it aptly illustrated the national myth of Czechs’ love of music, the lyricism of her stance and facial expression was also perfectly in keeping with the idea of the Czech national spirit. No less important were her closed eyes indicating the alleged Czech spirituality. Moreover, her ample oval face is supposed to be typically Czech and it is characteristic that there are also several allusions to Czech mythical past - the form of lyre, the linden wreath and the so-called old Czech hair dress. For Czechs these small details, which most foreigners fail to see, were important hints that the statue speaks neither Latin, nor German, but Czech. This paper was presented at the seminar “Multiple modernities, multiple antiquities”, organised by Collegium Budapest, in April 2003 1 Bloch, Peter, Grzimek, Waldemar, Die Berliner Bildhauerschule im neunzehnten Jahrhundert - das klassische Berlin, Berlin 1994, fig. 198. 2 Žákavec, František, Chrám znovuzrození, Praha 1918. 3 Petr Faster after: Moravcová, Mirjam, Národní oděv roku 1848, Praha 1986, fig. 9. 4 1858-1859, after: Novotný, Stanislav, ed., Rok Jana Nerudy v datech, obrazech, zápisech a vzpomínkách, Praha 1952, p. 24. 5 O.Audy et alii, ed., Jan Neruda v Obrazech, Praha 1951, tab.9a. 6 Zítek’s drawing of 1866 after: Šnajdr, Josef, ed., Národní divadlo, Praha 1983, fig. 18b. 7 Late Hallstatt bronze jewlery from Želenice district Kladno, after: Památky archeologické a místopisné n. 1, 1855. 8 Národní divadlo, Praha 1982, fig. 11. 9 Národní listy 1865 (quoted in: Matějček 1934, 49). Cf. Marek 1995, 182; Haiko 1998. 10 O. Hostinský, „O významu a úkolu Národního divadla i přípravách k jeho otevření,“ 1881, cf. Jůzl, 1981, 58. 11 Hostinský in: Dalibor, 1869 (cf. Hostinský 1974, 15). 12 Hostinský in: Dalibor 1869 (cf. Hostinský 1974, 14). 13 Cf. Macura 1983, 91-92. 14 On nationalism and Hellenism in 19th century Europe cf. Leoussi, Athena S., Nationalism and Classicism: The Classical Body as National Symbol in Nineteenth-Century England and France, London - New York 1998. 15 Richmond, The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, inv. N. 62.31, after no. 17, Beck, Herbert, et alii, ed., Mehr Licht. Europa um 1770. Die bildende Kunst der Aufklärung, Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie, Frankfurt am Main 22. August 1999 bis 9. Januar 2000, München 1999, p. 37. 16 Tyrš, Miroslav, Laokoon, dílo doby římské, Praha 1873, VII-VIII: „Otázka po době Laokoonově stala se … otázkou převážně německou. Tam rozepře s největší důkladností a příkrostí se vedla, a výsledek byl takový, žeť strany sporné samy na ten čas žádného východu z ní nespatřují … Co tedy uvesti chci, nemohlo mi ovšem podnětem býti, abych vyšetřování toto vůbec podstoupil; avšak … octnul se přec vedle interessu čistě vědeckého aspoň v druhé řadě též jiný zřetel, který mne při práci … jakoby sílil a ku předu pudil - snaha totiž, aby zmatečná záhada ta - o které jinde po tolikerých pokusech jižjiž pochybováno, žeť spůsobem všeplatným ji rozřešit lze - na půdě slovanské konečně se rozhodla.“ 17 Cf. De Grummond, Nancy T., Ridgway, Brunilde S., eds., From Pergamon to Sperlonga. Sculpture and Context. Berkeley - Los Angeles - London 2000. 18 Mádl 1904, 69-70 (originally published in 1901). 19 Mádl 1904, 59, 61 (originally published in 1900). 6