HOW TO PREPARE FOR TESTS

advertisement

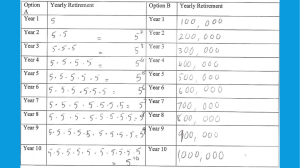

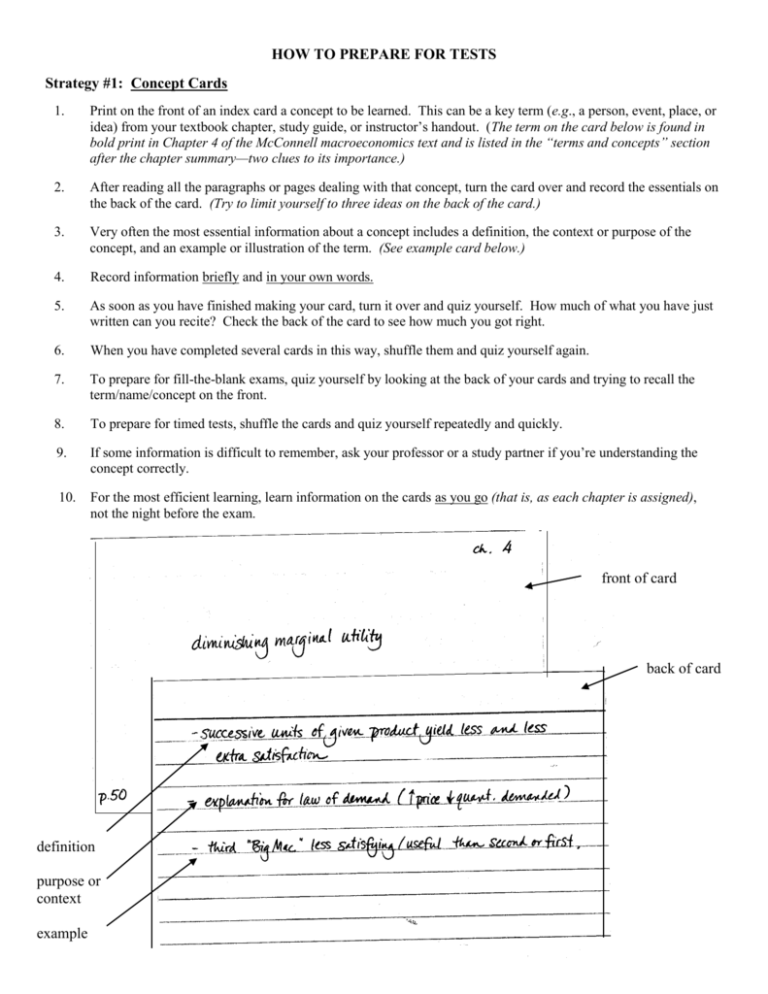

HOW TO PREPARE FOR TESTS Strategy #1: Concept Cards 1. Print on the front of an index card a concept to be learned. This can be a key term (e.g., a person, event, place, or idea) from your textbook chapter, study guide, or instructor’s handout. (The term on the card below is found in bold print in Chapter 4 of the McConnell macroeconomics text and is listed in the “terms and concepts” section after the chapter summary—two clues to its importance.) 2. After reading all the paragraphs or pages dealing with that concept, turn the card over and record the essentials on the back of the card. (Try to limit yourself to three ideas on the back of the card.) 3. Very often the most essential information about a concept includes a definition, the context or purpose of the concept, and an example or illustration of the term. (See example card below.) 4. Record information briefly and in your own words. 5. As soon as you have finished making your card, turn it over and quiz yourself. How much of what you have just written can you recite? Check the back of the card to see how much you got right. 6. When you have completed several cards in this way, shuffle them and quiz yourself again. 7. To prepare for fill-the-blank exams, quiz yourself by looking at the back of your cards and trying to recall the term/name/concept on the front. 8. To prepare for timed tests, shuffle the cards and quiz yourself repeatedly and quickly. 9. If some information is difficult to remember, ask your professor or a study partner if you’re understanding the concept correctly. 10. For the most efficient learning, learn information on the cards as you go (that is, as each chapter is assigned), not the night before the exam. front of card back of card definition purpose or context example Strategy #2: Charting Do you have two or more theories to learn? Will you be asked on the test to compare and contrast several individuals, events, stages, or ideas? Do you tend to focus on concrete realities, while your professor tests on abstract understandings? In any of these circumstances, making a chart can help you prepare for the exam: 1. Start with a title. 2. Then construct a chart that compares and contrasts the different stages, persons, or theories you need to learn: a. Utilize information from text and lecture to decide what categories to use; and b. Fill in the cells of the chart with information from text and/or lectures 3. Review the chart immediately. 4. Quiz yourself on the chart by reciting information without looking at it. Alternatively, set your chart aside and on another sheet of paper attempt to reproduce it--without peeking. Academic Learning Center 09/2008 Reading and Learning Center University of Northern Iowa 008 ITTC (319) 273-2361 Strategy #3: Timelines Do you have historical data you are trying to learn? Are you trying to follow an author’s explanation of some events that led to other events? Are you expected to understand the rise and fall of great civilizations and their contribution to Western civilization? Make a time line! 1. A time line can run horizontally (like examples shown below) or vertically (from the top you your page to the bottom). 2. Mark some especially important dates or eras on your line and indicate the important events that occurred then. 3. Fill in other key ideas, events, and persons. 4. If a large span of time can be labeled in some way (e.g., the Golden Age, a “blue period,” the Great Schism), bracket those years in some way. 5. To memorize this information, set your time line aside and recite the information. To demonstrate real mastery, find a study partner and teach that person all of the information. Strategy #4: Mapping Sometimes we must learn a large mass of information, all interrelated and extremely complex! Even if we were to read and reread the textbook forty times we couldn’t possibly understand what’s going on. When you find yourself in this situation, make a map. 1. Start with a title. What process or procedure are you attempting to understand? 2. Read the textbook material paragraph by paragraph, line by line, and doodle as you read. Try to picture what the author is saying. (See the two samples below) 3. You don’t have to be artistic. Sometimes just words in boxes are sufficient. 4. Don’t expect your map to be perfect on the first attempt. It is difficult to represent conceptual information graphically. You may want to use a pencil with a good eraser! 5. It is critically important to show the relationships among concepts. Represent these relationships with arrows or in some other way. If you’re demonstrating a two-way relationship, make sure your arrows flow both directions. 6. If you learn best through hearing, quiz yourself by reciting the information on your map, without peeking. If you learn best through your hands, draw the map again on a chalkboard or large notepad, without peeking. Note any errors and do it again. Academic Learning Center 09/2008 Reading and Learning Center University of Northern Iowa 008 ITTC (319) 273-2361