Making Voting Secret - Victorian Electoral Commission

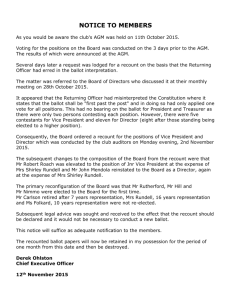

advertisement