Theories of Justice - King`s College London

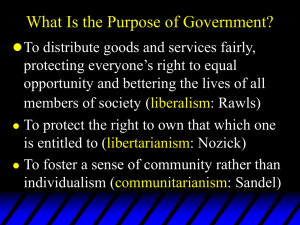

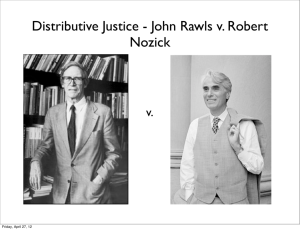

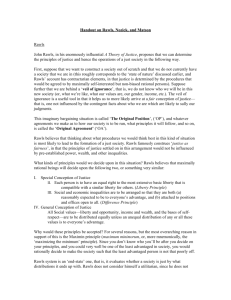

advertisement

AKC 5 General – Autumn Term 2007 – Social Ethics 29/10/07 AKC 5 – 29 OCTOBER 2007 THEORIES OF JUSTICE DR TIMOTHY GIBSON, KING'S COLLEGE LONDON Key Questions: What do philosophers mean when they talk about ‘justice’? Does justice necessarily mean equality of distribution? What are some key approaches to justice in contemporary moral philosophy? How might Christians approach questions of justice? ‘It is only from the selfishness and confined generosity of men, along with the scanty provision nature has made for his wants, that justice derives its origins.’ David Hume A Treatise on Human Nature (1739). Justice therefore has to do with the allocation of scarce resources amongst human agents. A practical example of a moral question involving ‘justice’: 100 candidates apply for a highly desirable position. By reference to what criteria are we to decide who should get the job? Aristotle offered a formal theory of justice (where justice is defined, but no content is added): ‘equals should be treated equally, and unequals unequally’ (see Nicomachean Ethics). This is called the principle of proportionality, and remains a key element of contemporary theories of justice: A has X of P B has Y of P so, so, A should have X of Q B should have Y of Q We need material principles to supplement formal theories of justice, since such principles give content to our conception of what constitutes a just distribution of resources. Aristotle thought distribution should be on the basis of merit, which is judged by the community. Aristotle’s is an example of a patterned theory of justice. Such an approach says that justice depends upon some traits(s) or characteristics of persons in order to discern a just distribution. So, in the job example, we might say, following Aristotle, that a just distribution of the job would be if it went to, say, the most conscientious, intellectually able and relevantly experienced applicant. The difficulty with a patterned theory of justice is that the allocation of resources in such a way could only be facilitated by continual interference by those (e.g. government) who decide upon the relevant traits in order to prevent people allocating resources as they wish to. In the job example, the selection panel might prefer to offer the vacancy to a demonstrably less conscientious/intellectually able/relevantly experienced applicant who they feel will fit in with the team. Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia (1977) Nozick argues for a non-patterned theory of justice, on Libertarian grounds, in which the distribution of resources is not dependant upon the traits or characteristics of agents, but upon the history by which they came to possess their holdings. Nozick’s approach is called the ‘Theory of Entitlement’. In this theory, a distribution is just if everyone has that to which s/he is entitled. To determine what people are entitled to, we have to understand the original position of holdings and possessions and ask whether their transfer was just. So the central question for Nozick is, ‘how did agents come by their current holdings?’ If I came by my holdings by legitimate means (say, if I didn’t steal them, or trick them out of people), then I am free to dispose of them as I wish (cf. patterned approaches to justice). AKC 5 General – Autumn Term 2007 – Social Ethics 29/10/07 It is therefore perfectly possible in Nozick’s schema for some members of society to have far more holdings than others. And it is inappropriate for government to intervene for the sake of an even distribution of resources. John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (1971) Rawls offers a very different non-patterned approach from Nozick’s. Rawls’s emphasis is on just procedures, rather than analysis of actual distributions (cf. Kantian ethics). Rawls believes humans are egoistic, self-interested, and will naturally seek to further their own ends. Rawls claims that a just society is one that would be chosen from behind a veil of ignorance, where individuals have no knowledge of their social status, natural abilities or conception of the good. The original position, as it is called, is a theoretical position in which agents imagine the procedures that will govern society, and ensure justice. Under such conditions, Rawls states that self-interested rational agents would choose a society informed by: o Equality in basic liberties (freedom of speech, right to vote &c.); o Inequalities of income/assets &c. only allowed insofar as they work to the benefit of all. Communitarianism Communitarianism conceives persons to be inherently tied to their social contexts. Adherents of this view (e.g. Alasdair MacIntyre) regard the Rawlsian approach as untenable, calling the veil of ignorance a chimera. We cannot but think about justice from a particular standpoint, communitarians argue, and it is unrealistic to suppose we might approach questions of justice from a position of imagined neutrality. Likewise, communitarians reject Nozick’s theory of entitlement, on grounds that notions of entitlement self-evidently vary across cultures (e.g. views of marriage). According to MacIntyre, in Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988), moral agents formulate their moral perspectives by reference to the tradition to which they adhere (e.g. Christian, Marxist, liberal! &c.). In MacIntyre’s approach, the tradition picks out various goods that are to be pursued by adherents. Justice, the distribution of resources, like any moral issue, is therefore bound up with serving those goods. For example, in Christian tradition, central goods might be identified as, say, selflessness, love, humility, other-regard. Thus Tim Gorringe, in The Sign of Love: Reflections of the Eucharist (1991) speaks of a just distribution of resources as (pace Rawls and Nozick) one in which self-interest is overcome for the good of sharing and mutual community. Thus, justice is defined by reference to such goods – if someone is extremely rich, but has attained their wealth through selfishness, the Christian might regard this distribution as unjust, on grounds that it does not instantiate the goods of the Christian community. Further Reading LaFollette, H. (Ed.) (2002) Ethics in Practice Oxford: Blackwell. Chs. 51 - 54 Horton, J. & Mendus, S. (Eds.) (1996) After MacIntyre: Critical Perspectives on the Work of Alasdair MacIntyre Oxford: Polity Press Full details about the AKC course, including copies of the handouts, can be found on the AKC website at: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/akc. Please join in the Discussion Board and leave your comments. If you have any queries please contact the AKC Course Administrator on ext 2333 or via email at dean@kcl.ac.uk. Please make a note in your diary that the AKC Examination will take place on Monday 21 April between 14.30 and 16.30. YOU MUST REGISTER FOR THE COURSE using the online form on the website. You will need to register for the exam separately, information will be provided next semester.