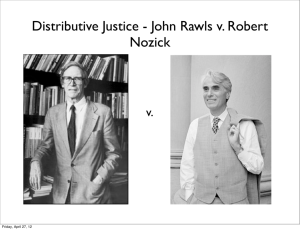

Robert Nozick: Distributive Justice

advertisement

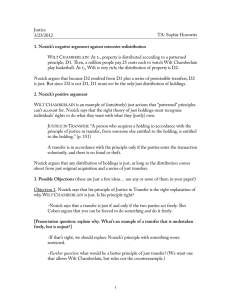

Robert Nozick: Distributive Justice Robert Nozick (1938-2002) Pellegrino University Professor at y Harvard University Books: Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974); Philosophical Explanations (1981);The Examined Life (1989); The Nature of Rationality (1993); Invariances (2001) A libertarian – in favour of the minimal, “night watchman” state: “protection against force, theft, fraud, enforcement of contracts, and so on, is justified; any more extensive state will violate persons' rights...and is unjustified” (ASU, ix) 1 The Entitlement Theory I In a wholly just world: 1) A person who acquires a holding in accordance with the principle of justice in acquisition is entitled to that holding. 2) A person who acquires a holding from someone else in accordance with the principle of justice in transfer, is entitled to that holding. 3) No one is entitled to a holding except by (repeated) applications of 1) and 2) The Entitlement Theory II Since we do not live in a wholly just world, there are actually three components to the overall theory: 1. Justice in acquisition of holdings 2. Justice in transfer of holdings 3. Rectification of injustice in holdings A distribution is just if it has arises in accordance with these three sets of rules – i.e. “if everyone is entitled to what they possess under the distribution” (236) 2 Types of Theories Nozick asserts that all theories of distributive justice can be categorized as: (a) Either end-result or historical, and (b) Either patterned or unpatterned Nozick’s entitlement theory is historical and unpatterned. (Marxist) socialism – “to each according to his need” – is a patterned tt d + end-result d lt th theory. Rawls’ theory, says Nozick, is an end-result theory So, the entitlement theory does not demand that the g from jjust acquisitions, q , transfers and distribution resulting rectifications be patterned (i.e., correlated with anything else e.g., moral merit, need, usefulness to society) Instead people are simply entitled to whatever they justly acquire, through acquisition or transfer, including holdings acquired through chance or gift. On Nozick’s view, any distribution is just provided it has the appropriate history, i.e., provided that it came about in accordance with the rules of acquisition, transfer, and/or rectification. 3 The Wilt Chamberlain Argument Suppose that holdings have been distributed according your preferred pattern D1 Suppose also that Wilt Chamberlain (19361999) is in demand as a basketball player and people are willing to pay to see him play Chamberlain signs a special contract under ¢ admission charge g which he receives a 25¢ for each home game. 1M people come to see him play, voluntarily paying the 25¢ charge. Chamberlain ends up with $250,000 that year, possibly more than anyone else in your society… This new distribution D2, says Nozick, is just: Everyone g , 1M people p p chose to trade had control over their holdings, some of their holdings to watch Chamberlain play. (And who are we to tell them what they should have spent their money on?) No one can claim injustice: D1 was just by hypothesis, D2 arose from D1 via only just, voluntary transfers. A (patterned) socialist society “would have to forbid capitalist acts between consenting adults” (240)… 4 Rights & Self-Ownership This can be generalized: “…no end-state principle or distributional pattern principle of justice can be continuously realized without continuous interference in people’s lives.” (240) And that is what makes it unjustifiable: Interference of this sort violates people’s rights The ffamous fi Th firstt liline off ASU (ix): (i ) “Individuals “I di id l h have certain t i rights, and there are things no person or group can do to them (without violating their rights.)” More on Redistribution Patterned theories are recipient focused – they restrict an individual’s right to transfer holdings to another person f that person’s for ’ benefit. f (E.g., note on the application of the difference principle within a family, 241) Patterned theories always eventually necessitate redistribution (since holdings will always deviate from the preferred f d pattern tt over time). ti ) “Taxation of earnings from labour is on par with forced labour.” (242) 5 Property Rights As Nozick mentions, property rights are normally thought of as rights of disposition – a property right in X entitles the right holder to determine what will be done with X. Though side-constraints may be set by other rules operating in a society: “My property rights in my knife allow me to leave it where I will, but not in your chest” (243) E End-result d lt principles i i l iimpose a similar i il (b (butt more startling) t tli ) constraint: They give each citizen an enforceable claim on other people’s property—their actions and labour Lockean Acquisition Locke: We acquire property rights in unowned things by “mixing our labour” with those things. Nozick: There are some problems with this view. What’s the scope of my acquisition? (a whole planet?) Why is mixing a way of gaining property rights, rather than losing them? (e.g., a can of tomato juice poured into the ocean)) If we think of gaining property rights as adding value (rather than as ‘seepage’ from self-ownership), why does the right extend to the whole object, rather than just to the value added? 6 The Lockean Proviso Locke: There should be “enough and as good left for others” Nozick: Our acquisition ‘should not make others worse off’ According to Nozick, this can’t be interpreted to mean that the proviso is violated if others are worse off in terms of their opportunities to appropriate (otherwise it leads to a regress argument objection, 246). Instead, it must mean that people are made no worse off in some other respect. What’s the “appropriate baseline for comparison”? Nozick does not really say… “whether or not Locke’s particular theory of appropriation can be spelled out so as to handle various difficulties, I assume that any adequate theory off justice in acquisition will contain a proviso similar to the weaker of the ones we have attributed to Locke.” (247) Nozick: the proviso is violated if someone appropriates all of something necessary to life or ends up the sole owner of some necessary resource when all other supplies have b been d destroyed. t d Of special note: The (ambiguous) medical researcher case, 248. 7 Criticisms of Rawls What is a theory of distributive justice supposed to distribute? The total benefits of cooperation? (i.e., all wealth of society) or, The incremental benefits of social cooperation? (i.e., the wealth that wouldn’t have existed apart from social cooperation?) Rawls, says Nozick, does not distinguish these, but simply assumes the first… Perhaps we can’t adequately discriminate individual j p product’ of cooperation? p ((I.e.,, contributions to the ‘joint’ then we would have a practical need for some principle of distribution.) But, says Nozick, we can: Prices, e.g., fairly accurately reflect the value of the marginal product of individual contributions. Moreover, Rawls assumes that individual contributions can at least sometimes be isolated: Otherwise, how would we know to whom we ought to offer incentives? 8 More Criticism The focus on groups rather than individuals in the OP, says Nozick, is ad hoc and inadequately explained. Moreover, why include only people in “normal range” – “why exclude the group of depressives or alcoholics or the representative paraplegic?” (253) Why assume that the least well endowed can expect the willing cooperation of the better endowed in a redistributive di t ib ti scheme? h ? R Rawls l says th thatt th the diff difference principle is offered as a necessary condition for the good of all, but the better endowed will still have grounds for complaint under the principle: a principle that favoured them might also provide the benefits of social cooperation. 9