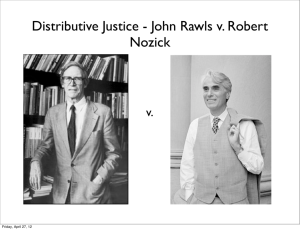

Handout on Rawls, Nozick, and Matson

advertisement

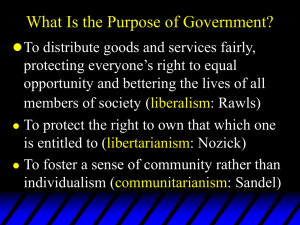

Handout on Rawls, Nozick, and Matson Rawls John Rawls, in his enormously influential A Theory of Justice, proposes that we can determine the principles of justice and hence the operations of a just society in the following way. First, suppose that we want to construct a society out of scratch and that we do not currently have a society that we are in (this roughly corresponds to the ‘state of nature’ discussed earlier, and Rawls’ account has contractarian elements, in that justice is determined by the procedures that would be agreed to by maximally self-interested but non-biased rational persons). Suppose further that we are behind a ‘veil of ignorance’, that is, we do not know who we will be in this new society (or, what we’re like, what our values are, our gender, income, etc.). The veil of ignorance is a useful tool in that it helps us to more likely arrive at a fair conception of justice— that is, one not influenced by the contingent facts about who we are which are likely to sully our judgments. This imaginary bargaining situation is called ‘The Original Position’, (‘OP’), and whatever agreements we make as to how our society is to be run, what principles it will follow, and so on, is called the ‘Original Agreement’ (‘OA’). Rawls believes that thinking about what procedures we would think best in this kind of situation is most likely to lead to the formation of a just society. Rawls famously construes ‘justice as fairness’, in that the principles of justice settled on in this arrangement would not be influenced by pre-established power, wealth, and other inequalities. What kinds of principles would we decide upon in this situation? Rawls believes that maximally rational beings will decide upon the following two, or something very similar: I. Special Conception of Justice II. Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive basic liberty that is compatible with a similar liberty for others. (Liberty Principle) III. Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both (a) reasonably expected to be to everyone’s advantage, and (b) attached to positions and offices open to all. (Difference Principle) IV. General Conception of Justice All Social values—liberty and opportunity, income and wealth, and the bases of selfrespect—are to be distributed equally unless an unequal distribution of any or all these values is to everyone’s advantage. Why would these principles be accepted? For several reasons, but the most overarching reason in support of this is the Maximin principle (maximum minimorum, or, more mnemonically, the ‘maximizing the minimum’ principle). Since you don’t know who you’ll be after you decide on your principles, and you could very well be one of the least advantaged in society, you would rationally decide to make the society such that the least advantaged person is not that poorly off. Rawls system is an ‘end-state’ one, that is, it evaluates whether a society is just by what distributions it ends up with. Rawls does not consider himself a utilitarian, since he does not think folk in the original position will voluntarily trade off a greater sum-total of goods for some to the disadvantage of others, although he does believe that rational folk in the original position can rationally trade off some liberties (although not basic ones) and allow some inequalities, just so long as they advantage everyone and disadvantage no one. Rawls sees his system as more Kantian, and representing Kant’s idea about society as the ‘Kingdom of Ends.’ Nozick Nozick can be viewed as the arch-enemy of Rawls, and wrote his famous Anarchy, State, and Utopia in reply to A Theory of Justice. Nozick’s theory is libertarian, in that it favors the maximization of personal rights and liberty over any operations of the state that seek to curtail them, even such operations are well-meaning (eg, welfare, etc.). First, Nozick defines the idea of The Minimal State. The minimal state is ‘the most extensive state that can be justified. Any state more extensive violates people’s rights.’(614) The minimal state is one whose sole purpose is to guarantee the continued free exercise of the rights of its citizens, and the abridgment of any rights (eg, to murder) is justified only if this abridgment guarantees in turn a right all rational people would wish to have (eg, to not be murdered). Nozick wishes to challenge theories of justice and systems of distributive justice that warrant bloating the state and it’s abilities to curtail individual rights with certain goals of societal benefit in mind (read, Rawls). “In this chapter we consider the claim that a more extensive state is justified, because [it is] necessary (or the best instrument) to achieve distributive justice.” Nozick does not wish (in the passage we have sampled) to discuss justice along all range of applications, but only justice in distribution of goods, moneys, property, rights, etc. Nozick’s view about justice in holdings is called ‘entitlement theory’. In brief, entitlement theory says that a distribution of goods in a society is just if everyone has that to which he or she is entitled. Entitlement theory would need to satisfactorily establish when and how it is just to: 1) Acquire previously unowned goods. 2) Transfer previously owned goods. 3) Rectify an injustice in (1) or (2) by retransfer (really (3) comes under (2)). And, we need a closure clause: (4) No one is entitled to anything they have other than by (1)-(3) Nozick does not wish in detail to flesh these out, although he does think that Locke was going a long way toward establishing (1) with his concept of coming into property by ‘mixing one’s labor’ with what was previously unowned. He also tends to think that any transfers are justified if they are voluntary and do not harm another in denying them their rights. Nozick is mostly intent on denying any theory of distributive justice that is ‘patterned’. “Let us call a principle of distribution patterned if it specifies that a distribution is to vary along with some natural dimension, weighted sum of natural dimensions,[etc]...And let us say a distribution is patterned if it accords with some patterned principle.” Simplistic examples of patterned distributions: 1. Distribute on the basis of IQ. 2. Distribute on the basis of moral worth. 3. Distribute on the basis of good looks. 4. Distribute in such a way that everyone receives at least 20,000 a year, by taking away income from those who make more than 20K and giving it to those who make less than 20K until each and every person makes at least 20K. If such a distribution cannot allow for everyone to make at least 20K, distribute so that everyone receives the same minimal amount. Nozick also calls such patterning, and governments that operate according to some patterning principles, as following end-state principles (they are called end-state principles since there is a certain end in mind, namely, a certain distribution. Communist Russia was, ideally at least, endstate, since it patterned distributions so that everyone had a standard of living approximately equal, a job, and no private property). Problems with Patterning: Liberty upsets patterns, and patterning upsets liberty. a) The Wilt Chamberlain example. b) Bequeathing/gifting problems. c) Entrepreneurial problems. Summary: “Patterned principles of distributive justice necessitate redistributive activities. The likelihood is small than any actual freely-arrived-at set of holding fits a given pattern...From the point of view of an entitlement theory, redistribution is a serious matter indeed, involving, as it does, the violation of people’s rights. (An exception is those takings that fall under the principle of the rectification of injustices).”(622) One of the main problems of patterned theories is that they are un-historical, that is, they pay no attention to how things came into existence, who made them. They seem to think that we can just look at a pattern of distribution and assess whether it is just w/no attention to the past facts. Also, patterning upsets personal liberty since it makes other people somehow entitled to what is yours and yours only, namely, the fruit of your labor and what you have justly come to hold. “Taxation of earnings from labor is on a par with forced labor.” “When end-result principles of distributive justice are built into the legal structure of a society...[they result in] each person [having] a claim to the activities and the products of other persons, independently of whether the other persons enter into particular relationships that give rise to these claims, and independently of whether they voluntarily take these claims upon themselves....This process...makes them a part owner of you”(623)