January 20, 2011

advertisement

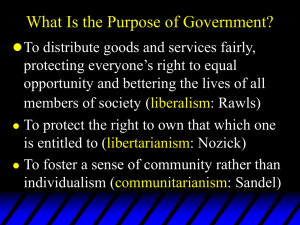

January 20, 2011 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Argument 1: Intuitive Equality of Opportunity Argument 2: Social Contract Nozick and Libertarian Justice Nozick on Entitlement Initial acquisition and the Lockean Proviso Nozick’s Intuitive Argument for Libertarianism Nozick’s Self-Ownership Argument Principle 1: Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all. Principle 2: Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both – a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged, and b) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity. Priority rule 1 (The Priority of Liberty): The principles of justice are to be ranked in lexical order (that is, the first principle takes priority over the second principle) and therefore liberty can only be restricted for the sake of liberty. Priority rule 2 (The Priority of Justice Over Efficiency and Welfare): The second principle of justice is lexically prior to the principle of efficiency and to that of maximizing the sum of advantages; and fair opportunity is prior to the difference principle. 1. 2. Rawls has two normative arguments for his theory of justice. The Intuitive Equality of Opportunity Argument. The [famous] Social Contract Argument. His theory is not derived from these arguments they are meant to show that we ought to favour his conception of justice: i.e., they are normative. They are separate arguments: if you do not accept the first you can turn to the second; if you do not accept the second you can fall back on the first – only if both fail will Rawls’ work lack justification. No justification, no Commitment! Prevailing argument for unequal distribution is through equal opportunity: an unequal distribution is justified if everyone had an equal opportunity to compete. Advocates of equal opportunity say that it is fair for people to have unequal shares if it is the result of choices, efforts and actions. But they accept that its unfair if people are disadvantaged by morally arbitrary factors, factors that pertain to circumstances that were not chosen by them. But he claims, when we identify the intuition behind the EO view that renders it attractive we will see that the position above fails to live up to our expectations. What we find intuitively attractive is the suggestion that a fair competition is one in which no one is disadvantaged by something undeserved [unchosen]. That is why we agree that no one should be made to be worse off because of racial, gender or class circumstances, these are morally arbitrary [unchosen]. This could be articulated more formally as follows: distributive shares ought not be determined by factors that are arbitrary from the moral point of view. The standard Equal Opportunity suggests that one’s social circumstances are morally arbitrary and so one ought not be advantaged by them. Thus we need fair competition that ameliorates social advantage. But, natural capacities and talents are just as morally arbitrary and so we must consider the advantage that they bring in competition. The standard equal opportunity view does not apply to natural talents and abilities, thus it fails to consider all morally arbitrary factors. The standard equal opportunity view claims that by counteracting social contingencies (race, gender or class) everyone has an equal opportunity to acquire social benefits. But this is not true, the naturally handicapped do not have that opportunity, their lack of success has nothing to do with their choices or their efforts. For Rawls we have to recognise that there are natural differences, differences in natural capacities and gear the basic structure of our society so that these work to the benefit of the least fortunate. Notice we are led to a Rawlsian conception of justice, and the difference principle, from considering the standard and prevailing view of what constitutes a just distribution, the equal opportunity view Rawls’ social contract is neither historical nor hypothetical, it is a thought experiment by which we can tests our intuitions about justice. Rawls seeks a new device allowing us to tease out the implications of moral equality for a theory of justice, by allowing us to think about justice free of the influence our own situations bring. He offers us his own version of the initial pre-contract situation, he calls this the ‘original position’ – behind a ‘veil of ignorance’ - whereby none knows what position in society they will hold, their class, race, gender, religion, how they have fared in the natural lottery, their physical capabilities and of character traits – all obscured. A societies principles of justice are chosen from the original position – behind the veil. Its difficult to imagine being in this position! BUT: The purpose of playing the role of a contractor in he original position is to test our moral intuitions about justice. It has been likened to the way we ask a child to divide a cake without knowing which slice they will get. The child is in something like the original position; they know that, when all is said and done, they will get a share, but they do not know what share they will get. Yet they have one thing up their sleave, they choose how the good is divided. In the original position no one can influence the selection process to favour themselves. “The idea here is simply to make vivid to ourselves the restrictions it seems reasonable to impose on arguments for principles of justice, and therefore on these principles themselves. Thus it seems reasonable and generally accepted that no one should be advantaged or disadvantaged by natural fortune or social circumstance in the choice of principles. It also seems widely agreed that it should be impossible to tailor principles to the circumstances of one’s own case”. The original position embodies a certain conception of equality, one whereby none of us knows anything about their natural talents nor social circumstances, we are all equally ignorant of the factors that might give us an advantage Asks us to extract the consequences for justice from this position of equality. For Rawls imagining this allows us to remove the sources of bias from our thinking and only then do we seek to reach unanimity about the principles of justice we employ. If we agree that in the ‘original position’ contractors reach an agreement about justice from a position of equality then Rawls has been successful. Contractors begin in the ‘original position’ and behind the veil of ignorance Contractors are rational and self-interested agents who, while ignorant of specifics know that we will have a life plan and that this will require both liberties and social primary goods Based on the maximin principle the contractors agree to pronciples of justice that will maximise what they would get if they found themselves in the minumum (worst) situation In making this decision behind the veil of ignorance contractors much choose by considering the perspective of every other contractor, because when the veil is lifted they could end up in any position. The 1970’s was a period in which Keynesian welfare liberalism came under attack, but the 1980’s neoliberal orientations (Reagan, Thatcher – but also Blair and Clinton) had come to dominate. While neoliberal politics and libertarian politics overlap to some degree (both value free markets, both have engaged in criticisms of social spending by states) they are distinct – libertarianism is more centrally bound up with a moral argument, its claims are not, centrally, about efficiency they are about morality. If they promote free markets and small governments they do so for moral reasons and not primarily on grounds of efficiency. Libertarianism is built around a strong defence of universal rights and a politics centred on rights holding individuals – for a libertarian the best way of defending liberty and equality is through a strong system of individual rights protecting the liberty of all individuals. “Individuals have rights, and there are things which no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights). So strong and far reaching are these rights that they raise the question of what, if anything, the state and its officials may do” (Nozick 1974, ix) Law, legislation, government regulation and so on should be reduced to the minimum required to establish the conditions for individual autonomy, that minimum is constituted by what is required for the defence of individual rights and no more. Assume (perhaps contrary to fact) that everyone is entitled to their current holdings – the current distribution is legitimate. Over time exchanges will be made and the distribution will change: How can we know if a future distribution will be legitimate? If all exchanges are free, un-coerced exchanges of goods, then the holdings, whatever they may be, in the future will also be just. Any coercive taxation on these holdings to compensate others is unjust. It coercively takes what is rightfully mine and gives it to another person who has no legitimate claim on it. The only taxation that is just is that extracted to provide the institutions necessary for free exchanges – institutions I rely upon – such as the police and justice system. Three principles that an entitlement theory must grapple with: The principle of transfer – whatever is justly acquired can be freely transferred. The principle of just initial acquisition – provides an account of how people initially obtain legitimate holdings that they can transfer. The principle of rectification of injustice – provides an account of how to deal with holdings that were unjustly acquired or transferred. This is a historical conception of justice because in order to see if any distribution is just I have to consider the historical facts about acquisition and free transfers that lie behind it. Whatever results from free exchanges based legitimate entitlement is just, even gross distributive inequalities – so Nozick tells us “from each as they choose, to each as they have chosen”. The state should be limited to those functions required by individual citizens to protect them from force, theft, fraud and for the enforcement of contracts – establishes the boundary conditions for free exchange of legitimate holdings. A state should protect our right not to be forced to do things, it ought to protect our liberty –conceived in a tight way, freedom from coercion by others, including the state. A state that exceeds this boundary will end up forcing people to do things that they do not want to do - an unjustified infringement of their liberty. Public education, health care, transport … are things which would lead us to violate people’s rights because we could only fund these them via coercive taxation. Principle two of Nozick’s conception of justice requires an account of what a legitimate initial acquisition amounts to (Australia? New Zealand? The USA?...) Nozick borrows from Locke’s theory of property (recall last week). I own my self – I am a self-proprietor, this includes ownership of my abilities and talents. I can appropriate the un-owned in nature by working upon it, that is by applying abilities to it to shape it according to a rational plan. The only proviso on my appropriation of nature is that I leave “enough and as good” for others to appropriate – that is, an acquisition must not disadvantage others. Locke knew that many of the acts of acquisition (land enclosures undertaken in England) did not respect the Lockian proviso that acquisition leave “enough and as good” for others. It advantaged some to the disadvantage of others. But, consider the ‘tragedy of the commons’ – common land is not used efficiently/productively and subject to depletion – there is no guarantee of return for effort, so no rational motivation to make an effort. Private ownership results in more efficient and productive use of land and provides a greater guarantee of return for effort. Further private ownership in bringing greater productivity brings a boon to all – jobs and a greater quanta of produce for consumption Thus there is no injustice in allowing private appropriation; it does not leave others worse off. The test for just acquisition is based on Locke’s proviso – that acquisition must leave “enough and as good” for others = acquisition morally ought not make others worse off – if Locke’s claim about private use is correct meeting this seems straightforward. Yet one can accept the above and claim that the same argument would justify a communal appropriation and use of land – it may demonstrate leaving the land a commons is inefficient and unproductive but does not specifically justify private as opposed to collective use. Further the ‘first-come, first served’ principle is questionable, the first person to acquire the land is not necessarily the best (most productive) person to acquire it, perhaps the community is worse off allowing that person to acquire it rather than some other or opting for communal use. So there are problems with the Lockean account of legitimate initial acquisition. These go deeper than the fact that, historically speaking, force has been the tool whereby holdings have been acquired. But it is possible that there an alternative stronger account of legitimate initial acquisition can be given. What is a more important question is whether he can provide a normative justification of libertarian conceptions of justice generally – if that can be done then libertarians can revisit the question of legitimate acquisition. He has two arguments one an intuitive argument the other an argument from self-ownership. Thought experiment Imagine we are starting from a position with a just distribution of resources. Imagine (Harlem Globetrotter) Wilt Chamberlain joins a basket ball team in his contract demands, over and above his regular salary, that he may add 25 cents (paid directly to him) to the cost of entry to all games he plays in. Now suppose 1 million people attended his games so that at the end of the season he recieves $250,000 extra. What is the injustice here? Each person who saw him play willingly transferred 25 cents to him in exchange for the pleasure. If the initial distribution was fair, and if all who attended the game freely paid the additional 25 cents to see Wilt play the fact that Wilt now has a larger slice of the pie is not an injustice. By what right could the state then interpose itself and demand that Wilt give a portion of that money for the benefit of some third party? This third party had no claim at the beginning of the season, when the distribution was just, how do they then come to a legitimate claim on Wilt’s $250,000? Nozick says that intuitively we agree there is no just claim on the extra $250,000 that Wilt has – if the initial holdings were fair and the only reason why he has the extra money is that people freely paid it to him in exchange for seeing him play then we would intuitively agree no one has a claim on Wilt’s extra share. This meets our intuitions about being able to dispose of legitimate holdings in any way we want – that you are free to dispose of your holdings as you chose. But it does not meet our intuitions about undeserved inequalities. A disabled person’s inability to increase their holdings is undeserved, they suffer a natural disadvantage, but we cannot say that they deserved this. Thus for many their intuitions lead to the idea that, in some manner, we need to deal with this. While Nozick has successfully appealed to our intuitions about our right to dispose of our holdings as we chose he has not done justice to our intuitions pushing us to compensate for undeserved disadvantage. Nozick acknowledges this, which weakens the intuitive case and means he requires some other justification. Based on the Kantian notion that human beings are ends-in-themselves; Partly that means that we are never to be used as a means to the ends of others, partly it means that we are beings who can determine our own purposes and goals, we are beings who can ‘shape’ our own life plan according to our own purposes and goals (workmanship). Most primitively = human beings have the right not to be used as a vehicle for another’s ends, no human being should be sacrificed or have their interests sacrificed for the sake of others. Recall the workmanship model of ownership from last week: each individual freely shapes their own life according to their own rational life plan. For Nozick self-owernship is an interpretation of the Kantian notion that human beings are ends-in-themselves. Society must respect rights because rights reflect the Kantian principle that people are ends-in-themselves. This places strict limits on what can be asked of us in the name of others and a theory of rights that coheres with this ought to help define those limits. a libertarian theory treats people as “persons having individual rights with the dignity this constitutes. Treating us with respect by respecting our rights, it allows us, individually or with whom we choose, to choose our life and to realise our ends and our conception of ourselves, insofar as we can” (Nozick 1974, 334). For Nozick this is counter to the Rawlsian idea that the state may redistribute in the name of the worst off – for that would be negating our right to use our resources as we please in pursuit of our own self-project. Rawls and Nozick agree there needs to be limits to what the state can do to individuals in the name of the collective: there are certain rights that are bedrock, however they do not agree on what rights these are. For Rawls the foundational right is to a fair share of social goods, including resources. For Nozick the most important rights are to selfownership. Rawls would agree that this is an important right but would disagree that one always has an absolute right over one’s property. Rawls suggests that goods produced by the use of talents can legitimately be appropriated by the state to benefit the least advantaged because while you have a right to use and benefit from those talents this does not include a right to gain unequal rewards on a morally arbitrary basis. Nozick feels Rawls’ position incompatible with selfownership because it suggests that I do not completely own myself. If I own myself completely then I own my talents completely. If I benefit from my talents in free exchange then, because I own those talents completely I should own whatever I receive in exchange for them completely. To reject this is to say that I do not own my talents completely, that someone else (the state) has a fair claim on my talents and the use of them. This negates my self-ownership. To tax me on what I earn from my talents in the name of redistribution violates my property rights and more fundamentally violates my right to self-ownership. For Nozick Rawlsian principles constitute a partial negation to classical liberal, Lockean, principle of self-ownership. The welfare liberal view fails to treat people as ends-in-themselves and, as with the utilitarian view, permits using some people (tax payers) as a means to the ends of other people, the socially or naturally disadvantaged. Thus: Rawlsian redistribution (or any coercive government intrusion into market exchanges) is incompatible with recognising people as self-proprietors. Only unrestricted capitalism recognises such self-proprietorship. Recognising people as self-proprietors, recognising selfownership, is crucial to treating people as free and equal.