Additional Reading

Identifying Corporate Information Needs

The steps to take for conducting an information audit.

09/01/97

The Information Advisor

Page S1

COPYRIGHT 1997 FIND/SVP

This issue of The Information Advisor's quarterly Knowledge Management

Supplement focuses on the key steps for conducting an information audit. An

information audit is one of the critical first steps of any knowledge management

program, and should directly involve the information professional as a leader or the

leader in putting together an effective project.

Conducting an information audit provides the necessary snapshot of an organization's

current use of information so that a proper diagnosis of the efficiency of the overall

institution's use of information can take place. It also presents an opportunity for you to

take on a higher profile job and gain organization-wide credibility by expanding your

duties in a more strategic role.

YOUR ROLE

While you may already know why you're well suited to do this kind of work, it's still

worth articulating some of the reasons. Here are just a few of the vital skills and

capabilities that you bring to the table:

* An understanding of the organization as a whole, and how the parts work together

* An understanding of external sources and all types of information content

* The ability to organize, codify, and categorize knowledge

* The ability to identify inefficient or improper uses of information, whether that problem

relates to the quality of the actual content, appropriate format, or effective access

methods.

* The ability to apprehend and elaborate on users' information needs. For example, the

skills required for conducing a basic "reference interview" is ideal training for querying

staff about their day to day uses of information. Chun Wei Choo, a faculty member of

the Information Studies Department at the University of Toronto, says that this skill is

"fundamental" to the audit process.

Unit 1 Identifying Corporate Information Needs

Dow Jones InfoPro Resource Center

9

* The ability to improve the value of the information going to employees by evaluating

it, filtering it, abstracting, and providing a broader organizational and/or industry context.

Guy St. Clair, President and Founder of InfoManage/SMR International, and a past

president of the Special Libraries Association, says that you should be your

organization's "point person" and be "very active in setting up the meetings, working

with [any] consultants on the survey instrument, and bv 'talking up the advantages of

the audit."

(For a broader discussion on the information professionals role in knowledge

management, see The Information Advisor, Vol 9, No. 3, March, 1997, Knowledge

Management Supplement no. 1)

This article will provide a basic checklist of practical tips and strategies for starting an

information audit, grouped into the following five areas:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Getting the Ball Rolling

Conducting Interviews

Organizing and Presenting Results

Follow Up

Typical Pitfalls and Mistakes

Note that this article is a very abbreviated discussion of a fairly complex process. For

more detailed instructions, see the items listed in the "Further Resources" section at the

end of this supplement.

WHAT IS AN INFORMATION AUDIT ?

Before getting into the nuts and bolts of the information audit , let's first define it. The

following is one offered by Edwin M. Cortez and Edward J. Kazlauskas, in their article

"Information Policy Audit: a Case Study of an Organizational Analysis Tool," published

in the Spring 1996 issue of Special Libraries (pp 88-97):

"...the term information audit is a generic term used to designate a number of

strategies for studying the effectiveness of information flow within an organization. The

process for conducting this type of audit is also adapted from communications literature.

It can be defined as a fact-finding, analysis, interpretation, and reporting activity that

studies the information policies, structure, flow, and practice of an organization (citing:

Goldhaber, Gerald et al. Information Strategies: Pathways to Management and

Productivity. New Jersey. Ablex. 1984, pp.334,336). The purpose of the audit includes

the collection of data concerning the efficiency, credibility, and economy of the

organization's information handling activities and practices; the provision of adequate

policies which oversee these activities and practices (including those that govern

guidelines, functions, and budgets); and the development of recommendations for

action tailored to the organization's specific situation."

Unit 1 Identifying Corporate Information Needs

Dow Jones InfoPro Resource Center

10

St. Clair adds that an information audit is not only an attempt to determine what

information is being managed, but how well it is being managed, and therefore

encompasses the concepts of accountability and responsibility.

GETTING THE BALL ROLLING

How do you get an information audit started? It's probably not news to you that you

won't get off square one if you don't have upper management level support and some

champion or champions to help you along. In fact, Professor Choo advises upper

management not just to "be supportive" but to actively take part in the audit themselves.

After you feel that you've got that buy-in, you then also need to:

-- Get needed background data. Denham Grey, the president of GreyMatter, an

Indianapolis-based consulting firm, has conducted knowledge audit work for the help

desks of several firms, including U.S. Surgical, Texas Instruments, Mutual Life, Lincoln

Life, and Sprint. He advises gathering needed documents ahead of time as a way to get

the lay of the land of the organization. These may include organizational charts, job and

role descriptions, workflow routes, human resource manuals, in-house publications, and

more.

-- Get support from the rest of the organization. Just as you must have top

management support, you also need buy-in from those staffers who will be supplying

the data you require for the audit. Grey says that you should make sure you explain the

rationale and business reasons for the audit, to help allay any fears and encourage

participation. He says it's a good idea to distribute questions ahead of time so people

can collect their thoughts. Choo adds that it's also important to be clear in how the

results of the audit will be used. For example, will it be used to design an Intranet?

CONDUCTING THE INTERVIEWS

While there is a variety of ways that organizational information use can be ascertained,

the best way is still through personal interviews which can include one-on-one

interviews and focus groups. The mission of these interviews is to get people to open up

and talk about how and why they use information. Some experts advise getting an

outside person to conduct the interviews, which can result in getting more open and

honest results from the participants. In any case, a survey instrument should be

constructed that contains specific, but mainly open-ended questions.

While this article does not have enough space to detail all the questions that should be

asked in an information audit (see sources listed in the "Resources" section), these are

the basic areas you should always try to cover:

* Background data: Of course, you first need to get basic data on the person you are

interviewing. This includes job duties/functions and responsibilities, position, key

decision-making responsibilities, and so on.

* Names of information sources used to accomplish the above duties and

responsibilities. Mary Ellen Bates, who has written a just-published article on conducting

an information audit for the Fall 1997 issue of Library Management Briefings (see the

Unit 1 Identifying Corporate Information Needs

Dow Jones InfoPro Resource Center

11

Further Resources section), advises auditors to make sure that the interviewee

discusses sources found in all formats: e.g. print books and journals, CD-ROM,

Internet, electronic journals, professional online services, clipping files, Intranet

sources, online discussion groups, internal experts and so on. For each source named,

you'll need to find out:

-- Under what circumstances that source is selected -- How the source is accessed,

and in what format -- How often the source is accessed -- What specifically is done with

the information; that is, how is it utilized in a decision making process? -- What

happens to that information source after being accessed -- where does it go? -- Why or

why not the source proves to be successful in solving the user's information problem or

making the needed decision.

Questions should be worded carefully to elicit the most useful responses possible. Choo

advises asking the following three specific questions:

1. Rank and identify your three most vital sources and three most disposable, and

explain why.

2. Disregard all actual sources that you work with now. Imagine your ideal information

source and how would you use it.

3. Recollect and describe two or three recent incidents where you received important

information from a nonroutine source and acted on the information.

Once you have this data, you should be able to identify both the bottlenecks and

opportunity areas. Michael O. Luke, Information Strategist for Atomic Energy of Canada

Ltd in Manitoba, in a paper presented at the 1996 ASIS conference in San Diego said to

look for "natural information flows" and areas where existing pathways can be

enhanced. Bottlenecks, notes Mary Ellen Bates in Library Management Briefings, can

be financial (e.g. limited budgets or authority to make purchases), personal, (reluctance

to use library, lack of confidence in information gathering skills), physical/geographical

(e.g. international offices, field offices); technology (e.g. unable to access sources from

desktop) or lack of upper management support (e.g. no commitment to the value and

strategic role of information).

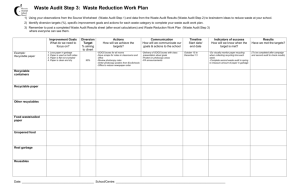

ORGANIZING AND PRESENTING RESULT

You may decide to illustrate the results of your information audit by creating an

"information map" which visually illustrates how information flows within the

organization. (Next quarter's Knowledge Management supplement will focus on

constructing an information map).

However you calculate and summarize the results of your audit, the results need to be

presented to all the key stakeholders in the organization -- these include, of course,

senior managers, but may also include department heads, systems people, and key

knowledge workers. It's a good idea to make a presentation to all the stakeholders at

the same time, to encourage a good dialogue among various parts of the organization.

FOLLOW UP

Based on the results of the audit, a task force should be created to make and

implement specific recommendations. Those recommendations can identify the need for

Unit 1 Identifying Corporate Information Needs

Dow Jones InfoPro Resource Center

12

new types of sources (which might include already existing external sources or the

internal design of new customized sources),whether current formats are appropriate,

methods for streamlining information access and sharing and so forth. Be sure too, that

there is some ongoing mechanism instituted to insure that users are continually able to

provide feedback on their evolving needs and uses of information. This will help the

organization provide information that is continually meeting changing needs. (An

excellent “Information Audit Action Plan" checklist is included in the Library

Management Briefings piece).

TYPICAL PITFALLS AND MISTAKES

Conducting an information audit can be a straightforward process, but there are some

common problem areas. Here are a few to avoid.

1. Mismatched Expectations. If different parties within the organization have varied

understandings of the audit's purpose, there will be problems when the audit is

concluded and it's time to take action. Everyone should have a full understanding of why

it is being conducted and what will happen when it is completed.

2. Ignoring the People Factor. Major problems can also occur if the auditors and

project team focus too much on the harder, quantifiable data and neglect people

concerns. Choo notes that you need to attend to the fact that some people are going to

worry that their work or information products won't be shown in a flattering light. He also

says that you can run into problems with people who prefer to hoard, rather than share

their information.

3. Ignoring your Organization's Culture. For any project to be successful, it has to be in

synch with how things work in your firm. Be sure you understand how your organization

operates (i.e. what are its values, beliefs, and ways of getting things done) and make

your project match it as closely as possible.

FURTHER RESOURCES

The following are the best sources we've seen on how to conduct an information audit

:

Books/Booklets

* The information Audit : An SLA Information Kit (Special Libraries Association,

Washington DC, 1995). This packet consists of a compilation of articles by various

authors.

* Rethinking the Corporate Information Center, FIND/SVP, 1995. Contains a sample

questionnaire for assessing user information needs.

Articles

Unit 1 Identifying Corporate Information Needs

Dow Jones InfoPro Resource Center

13

* "Build Intelligence into Your intranet," Michael Nanfito, Information Outlook, May,

1997, pp 16+.

* "The Information Audit : An Important Management Tool," Katherine Bertolucci,

Managing Information, June, 1996, pp. 34-35.

* Information Audits : What Do We Know and When Do We Know it?", Mary Ellen

Bates, Library Briefings, Fall, 1997 Highly Recommended.

* "Information Policy Audit: A Case Study of an Organizational Analysis Tool," Special

Libraries, Spring 1996, pp. 88-97.

* "Tools of the Trade," Marketing Research: A Magazine of Management and

applications, v.9, n2, Summer 1997, pp.31-35.

Information audits is also a topic frequently covered in Infomanage and the One

Person Library, both of these are published by SMR International, of New York, NY and

edited by Guy St. Clair.

Web Sites

In addition to the general knowledge management sites listed in Knowledge

Management Supplement, number 2, see also:

* Guidelines for Developing an information Strategy, Coopers & Lybrand

http://back.niss.ac.uk/education/jisc/pub/infrastrat Covers knowledge management

issues broader than conducting an audit, and written for a consortium of UK universities;

extremely detailed and useful.

* KM Briefs and KM Netzine are two new electronic journals devoted to knowledge

management that cover information audits . Link to http://www.ktic.com

In the next Knowledge Management Supplement:

How to Construct an Information Map. If you have created an information map for your

organization, please send email to RBerkman@aol.com

Copyright © 1998 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Unit 1 Identifying Corporate Information Needs

Dow Jones InfoPro Resource Center

14