art 201: handout 13, early christian and late antique art

advertisement

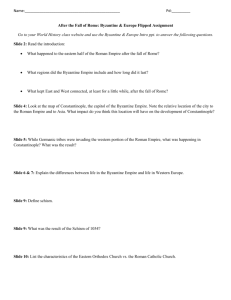

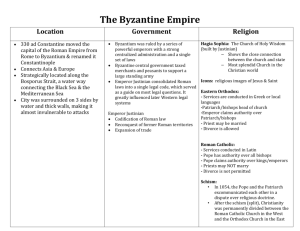

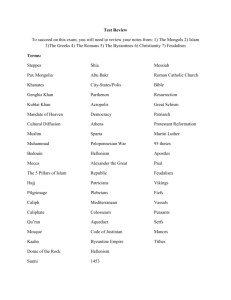

ART 201: HANDOUT 13, EARLY CHRISTIAN AND LATE ANTIQUE ART Catacombs: underground cemeteries outside Rome, these are the site of the earliest Christian paintings, which appear soon after 200 CE. Sketchy in style and presenting a limited number of motifs (the praying figure, the Good Shepherd, the Story of Jonah, etc.), it would seem that these images were seen as visual symbols of aspects of Christianity rather than as illustrations of Christian scenes (Painted Ceiling, Catacomb of Ss. Pietro and Marcellino, early 4th CE). Christian House, Dura Europos: the same twon preserves the best Early Christian housechurch, including a baptistry with crude but effective paintings (including the Good Shepherd). Built ca. 240 (destroyed 256). Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus: the coffin of a Mayor of Rome who died in 359. On the body, within columnar frames are depicted diverse scenes significant to Christianity. These do not present a coherent narrative, but their style is far more Classicizing than the 4th century sculpture of the Arch of Constantine. The Christian Basilica: in 313 CE the Christian religion was finally accepted by the Roman Empire, and the first large churches were built. These adapted the format of the Roman Basilica to Christian needs. Christian basilicas were generally timber-roofed, and often had a transept at the sanctuary so that the plan was cross-shaped. Behind the altar was an apse (a semi-circular vault). The Church of Old St. Peter's, Rome, begun in the 320s, is a good example of an Early Christian Basilica. The exteriors of these churches were generally of brick and rather plain (see the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia c. 425). All of the decorative emphasis was reserved for the interior, in order to give the religious service and experience the highest significance. The walls of the nave were often adorned with scenes of the Bible (Santa Maria Maggiore, 432-440), and the apse either painted, or, if possible, decorated with wall-mosaics. Santa Costanza, Rome: a domed round chapel built by Constantine's daughter Constantina c. 350. The mosaics on the aisle vaults still survive, and present a mixture of Christian and pagan motifs. Wall Mosaics: the favored medium for the decoration of Medieval church interiors, made of glittering glass cubes which gave a magical and spiritual luminescence to the religious scenes which they were used to create (Good Shepherd, Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, c. 425; Parting of Lot and Abraham, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, 432-440). They are used to decorate not only vaults and walls, but also domes (Baptism, Baptistry of the Orthodox, Ravenna, 458). The style is moving towards spiritual abstraction, but still retains vague naturalistic references. Classicism: the attempt to evoke the naturalistic style and noble idealism characteristic of the dominant artistic style in the Mediterranean from the 5th century BCE through the 2nd century CE. An early example is the ivory panel of the Symmachi carved ca. 400, and depicting a sacrifice by a priestess. Another ivory, done in Constantinople in the early 6th century, depicts the Archangel Michael floating before and above an architectural niche. The style of this ivory recalls Greek art, but its ethereal character is Medieval. The Vienna Genesis: an early illustrated manuscript of the first book of the Bible, probably done at Constantinople in the early 6th century. Painted scenes (Rebecca at the Well) at the bottom of each page illustrate the text in continuous narration; the style is not unlike that of Trajan's column in Rome. 1 ART 201: HANDOUT 14, BYZANTINE ART Constantinople: founded by Constantine in 330 at the entrance to the Black Sea to be the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, became the capital of the Byzantine Empire and a great artistic center. The Empire is named after the Greek name for Constantinople (Byzantium). Justinian: Byzantine emperor 527-565 who reconquered most of Italy and other parts of the western Mediterranean, and built much in Constantinople and Ravenna. An ivory depicting him as the Christian Roman emperor survives (c. 550). San Vitale, Ravenna: octagonal central-plan church built to Ravenna's patron saint 526-547. Decorated richly with mosaics, including two processions at the entrance to the choir. One of these shows Justinian and attendants, the other the Empress Theodora with attendants. These mosaics strike a balance between Classical naturalism and the symbolism characteristic of Medieval art. Transfiguration Mosaics: two versions of the Transfiguration, where Christ is hailed by God on a mountain top as his son in the company of Elijah and Moses, while three Apostles look on, are preserved from Justinian's reign. The first, in the apse of the Church of Sant' Apollinare in Classe near Ravenna, dates to 549 and presents a symbolic Transfiguration witnessed by Saint Apollinaire (the first bishop of Ravenna and twelve lambs. Christ is represented by a huge cross in a super-halo, and the Apostles are lambs. The second, in the apse of a church on Mt. Sinai in Israel, is figural, but is given no landscape setting. It dates c. 550-565. Hagia Sophia, Constantinople: Enormous church built by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus between 532 and 537. Not quite a central plan church (it's slightly rectangular), but dominated by its great central dome. The openwork carved ornament of the interior is exquisite and makes the architecture look curiously weightless. The mosaics on the interior are all post843, that is, post-Iconoclasm, and include a Virgin (Theotokos) with the Christ Child in the apse. Icon of the Virgin: preserved in a monastery on Mt. Sinai, this encaustic painting on wood was probably done in Constantinople around 550-600. Interestingly, it shows three different styles, a classical, three-dimensional rendering of the Virgin and Christ, a flat and schematic rendering of the two saints flanking her, a a sketchy and impressionistic one for the two angels behind her. Iconoclasm: a period between 726 and 843 when figural religious imagery was banned in the Byzantine Empire. Means: "image breaking." Macedonian Renaissance: a period between ca. 850-1025 when the Byzantine Empire was ruled by a dynasty from Macedonia in Greece and reached heights of political and cultural success. The art of this period was particularly classicizing. The Paris Psalter (Book of Psalms) of c. 950 shows a close adherence to Classical figural models in its style and reproduces much of the illusion of space seen in Roman painting (David Composing the Psalms). The Harbaville Triptych of the mid 10th century shows a similar Classicizing style in ivory, as does the gold and enamel icon of the Archangel Michael of the 10th century. Both of these were devotional items for focusing one's prayers. 2 Hosios Loukas: a monastery in central Greece. Its main church (the Katholikon) was built ca. 1000-1030. It is decorated inside with expressive mosaics. Its exterior is brick and enlivened only by simple decorative patterns. An earlier and smaller church of the Virgin (c. 950) is attached to the Katholikon’s north side. Daphni near Athens: a monastery church built c. 1100 and decorated with mosaics in a classicizing style. The center of the dome preserves a stern Pantokrator (All-Ruler), the Christ of the Second Coming, who is hailed by prophets at the base of the dome. The four pendentives, or semi-domes which buttress the central dome, contain scenes of Christ's life (Annunciation, Nativity, Baptism, Transfiguration). A scene of the Crucifixion on a side wall in the nave is particularly classicizing in its style, but symbolic in its lack of realism, especially of space. Virgin of Vladimir: a painted wooden panel, originally done in the 12th century, and taken to Russia. It shows the Virgin holding the Christ Child in the sweet, if formal, style that often characterizes Byzantine art of the 1100s. Nerezi, Saint Pantaleimon: a chapel painted in fresco in 1164 (paid for by a member of the imperial family). Its scenes are more emotional than normal for Byzantine art (Lamentation), and show an evolution in Byzantine style from the formal to the emotional. St. Mark's, Venice: Cathedral begun 1063, a five-dome basilica based on the design of a church built in Constantinople by Justinian in the 6th century. Its interior is covered by mosaics in a Byzantinizing style, but mostly by local artists. Monreale, Sicily: a huge basilica church built by the king of Sicily in the 1180s with Byzantine style decoration. Its apse is decorated like a dome with the Pantokrator at its top. Below, in registers, is the Virgin and Christ child flanked by angels, then saints. The Fourth Crusade: in 1204 Crusaders on their way to the Holy Land instead sacked Constantinople and divided up the Byzantine Empire. Although the Empire was re-established in 1261 on a smaller scale, it never regained its old power, and finally fell when the Turks captured Constantinople in 1453. Late Byzantine painting: after 1261, Byzantine art went through its last great phase. The paintings are gentler and freer than previously, and show hints of a relative naturalism (although with powerful highlights on the drapery) in the figures similar to that of Italian painting of the 13th century (Anastasis or Resurrection, Kariye Camii, 1310-1320). Late Byzantine art and architecture heavily influenced the later Medieval styles of painting in Russia and the Balkans (Andrei Rublev "Old Testament Trinity", c. 1410-1420), as well as Russian religious architecture (Cathedral of St. Basil, Moscow, 1554-1560). 3 ART 201: HANDOUT 15, ISLAMIC ART Islam: a religion which arose in Arabia in the early 7th century (around 620-630). Developed by the prophet Muhammed, Islam believes that it worships the same basic deity as Christianity and Judaism, but is superior due to possessing the words of the prophet in the Koran (Quran). Moslems, as devotees of Islam are called, worship by facing the holy city of Mecca in Arabia and praying to their God (Allah) five times a day. Their churches, called Mosques, are halls for prayers and for Friday services, and have a wall, called the qibla , which faces Mecca. The center of the qibla generally is marked by a niche called the mihrab. Outside a mosque are towers, called Minarets, from which priests call the faithful to prayer. Fired by zeal, the Arabs burst forth from Arabia in 632 and by 740 had conquered an empire which stretched from Spain to India. After the 10th century the Arabs were gradually subjected by an eastern people who had been converted to Islam, the Turks. Dome of the Rock: built c. 687-691 in Jerusalem, this central plan shrine is richly decorated and encloses the rock on which it is believed Abraham planned to sacrifice his son Isaac in Genesis . The Arabs believe that they are descended from Abraham and that Muhammed was taken to heaven from this rock in 610 to hear the word of Allah. The shrine is clearly derived from Early Christian central plan churches. Mosque at Cordova, Spain: elegantly decorated rectangular structure, built ca. 786 and enlarged several times thereafter up to 965, notable for its gracefully curved horseshoe arcades and arabesque decoration. The domed niche in front of the qibla (965) is particularly beautiful. Later Mosques: the Turks developed a new type of mosque, called the four-iwan mosque which was usually associated with theological schools called madrasas . The four-iwan type has vaulted halls around a central court (Mosque of Sultan Hasan, Cairo, 1356; Mosque at Isfahan, Iran, 11th-18th). After the Turks took Constantinople in 1453 and renamed it Istanbul, they adapted the dome of a Byzantine church to create imposing structures notable for their impressively open interior space (Mosque of Selim, Edirne, Turkey, 1570-1574). The Alhambra: palace built at Granada in southern Spain 1238-1391. Notable for its beautiful curvalinear decoration (Muqarnas dome, 1354-1391), and courtyard gardens (Palace of the Lions, 1380-90). Calligraphy: Islamic art generally avoids religious imagery and the representation of humans; it is basically abstract. Often the decoration takes the form of calligraphy (Page of Koran, 9th10th), where individual verses are elevated to pure decoration (see also Mihrab niche from Iran, 1354). Islamic tiles: often ceramic tiles with elaborately stylized vegetation and inscriptions from the Koran decorate mosques (Mihrab from Isfahan, Persia, 1354). Islamic textiles: a popular form of Islamic art, textiles were used for a variety of purposes. They generally feature the same abstract imagery seen in other Islamic art (Maqsud, Funerary Carpet from Iran, Turkey 1540). Islamic pictorial art: Secular art may have figures. In Afghanistan, a school of manuscript illuminators evolved a notable school of figural painting in the 15th and 16th centuries that was transferred with the court to Iran. This featured bird's-eye perspective and flat two-dimensional 4 figures in lively compositions, often illustrating secular and erotic poetry or depicting everyday life (Kamal al-Din Bihzad, "The Seduction of Usuf,” c. 1494). 5 ART 201: HANDOUT 16, ART OF THE MIGRATION PERIOD The Dark Ages: often used to refer a period c. 600-750 when the twin shocks of the invasions of the German tribes into the old Western Roman Empire and the onslaught of Islam led to an almost total elimination of the urban life and the civilization of the Roman Empire in western Europe. Celtic-Germanic Style: an artistic style practiced by the tribes which invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. It is characterized by linear "animal interlace" ornament of great complexity, as well as use of many jewels for decoration (hence the “jewel style”) and was generally limited to small and portable precious objects (Purse Cover from the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial, c. 625). Later, the same general style is found in Viking art from Scandinavia (Animal Head, Oseberg Ship Burial, Norway, c. 835). Hiberno-Saxon Style: a style of Christian art which adapted the "animal interlace" of CelticGermanic art to church themes. Practiced in the British Isles, the style combined elements from Irish Christian art (Hibernia=Ireland in Latin), and Anglo-Saxon art. It flourished in the 7th and 8th centuries. The Man, Symbol of St. Matthew, from the Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 700) shows how artists of the style flattened figures into linear and abstracted pattern, but the facing page’s Cross is a good example of the beauty these artists achieved through the use of complex interlocking linear pattern, often with stylized animals in the line The same style appears in even greater complexity in the Book of Kells (c. 790), notably in the chi-rho page that begins the story of the birth of Christ in Matthew. ART 201: HANDOUT 17, CAROLINGIAN AND OTTONIAN ART Charlemagne: ruled a great empire comprising France, Germany, and northern Italy 768-814. Crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the Pope on Christmas Day, 800. Sponsored a Renaissance (French for "Rebirth") in the arts which aimed at reviving Classical art and learning. The resurgence of culture under Charlemagne and his successors is called the Carolingian Renaissance, and lasted throughout the 9th century. Palace Chapel, Aachen: built in northern Germany 792-805 by Charlemagne, it was a circular church based roughly on San Vitale at Ravenna. Unlike San Vitale, the Palace Chapel has a massive quality to its forms which looks forward to the developed Romanesque architecture of the 11th century. Plan of a Monastery, St. Gall: a paper plan for an ideal monastery made c. 820. The plan charts out a self-sufficient village dominated by a large basilica-plan church with a Westwork of towers flanking the main entrance. A Carolingian Westwork (c. 880) survives only at Corvey in western Germany.today; it has powerful towers flanking a projecting entrance (portal). Carolingian illumination: imitated and revived the forms of Early Christian illustrated religious books as far as the artists were able. The illustrations (St. Matthew) in the Coronation Gospels (c 800) imitate the style of Classical painting, and are likely by a Byzantine-trained artist. Later Carolingian artists practiced a more expressionistic style (Gospel Book of Ebbo, St. Matthew, c. 820) The most amazing of Carolingian manuscripts is the Utrecht Psalter, illustrated in pen and ink c. 820 (Psalm 23). It has metaphoric pictorial units which illustrate key phrases in each Psalm. These units are arranged in spatially unified settings on the model of ancient Roman painting, but the compositions were invented by the Carolingian artist. Carolingian illuminated manuscripts were given splendid covers made of gold, ivory and gems. The Lindau Gospels (c. 870) has a wrought gold triumphant Christ on the cross surrounded by expressive mourners. He is beardless, and the cover is thus based on an Early Christian prototype (probably a manuscript illumination). 6 The Ottonian Empire: after the final demise of Charlemagne's empire around 900, the next great cultural force in European history arose in Germany. Otto I was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome in 962, and the empire that he founded lasted as the greatest political and cultural force in Europe into the 11th century. Ottonian illumination at times adapts the imagery of Roman imperial art to show the ruler’s divine authority (Liuthar Gospels c. 996). Ottonian Churches: developed the Westwork or towered facade first seen in Carolingian churches; St. Michael at Hildesheim (1001-1031) shows the rough power of an Ottonian church with its multiple towers. In general, Ottonian churches appear squat and powerful. They often had two transepts, one at the entrance, and the other just before the altar, and both transepts were marked visually by massive towers. Ottonian churches remained timber-roofed, but were the immediate ancestors of Romanesque churches (interior fo St. Cyriakus, 973). Their crypts, basements with chapels for saints, were often vaulted. Ottonian art: in some ways a successor to the Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian art was less interested in Classicism, and more fascinated with the expression of spiritual values and feelings through visual images. This can be seen in the wooden Crucifixion of Bishop Gero (c. 970), where Christ suffers on the cross. It is also one of the first large-scale works of sculpture to be produced since the Roman empire. Bronze Doors of Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim: these hollow-cast double doors (1015) imitate the format of earlier Byzantine and early Christian doors (now mostly lost), but the scenes on them use the expressionistic Ottonian twisted poses to depict the significance for Christianity but showing an Opposition of the Fall of Man and Jesus. Ottonian manuscripts: these stressed a spiritual expressionism and fervor (Lectionary of Henry II, 1014), and thus looked forward towards a main trend in Romanesque art of the 11th and 12th centuries in Europe. The figures (Annunciation to the Shepherds) are consistently flattened, with spatial settings stylized (abstracted) from those the artist found in his classical models. Some Ottonian manuscripts show a survival of imagery celebrating the ruler’s status that had developed under the Roman empire (Otto III enthroned, Gospels of Otto III, 1000). Some Ottonian manuscripts were produced in nunneries. ART 201: HANDOUT 18, ROMANESQUE ART AND ARCHITECTURE Romanesque: the artistic style of western Europe from c. 1050 to c. 1150 in central France, to c. 1200 in the rest of Europe. So-called because the barrel-vaulted ceilings of Romanesque churches resemble the vaulting used in ancient Roman architecture. St. Sernin, Toulouse: a pilgrimage church built in northwestern Spain 1070-1120. The church's plan shows a basic geometry and its massive masonry makes it look powerful. It has a barrelvaulted nave with a groin-vaulted aisle to either side. The aisles continue back around the transept and the sanctuary. There are a series of radiating chapels at the back of the church, allowing pilgrims to venerate the relics of saints kept in the chapels even during masses. The west façade was to have been framed by large towers (never built), and another tower (the lantern) covers the “crossing” where the transept cuts across the main axis of the church. The crypt preserves a relief image of Christ in Majesty signed by the sculptor Gelduinus in 1096; it is based on ancient Roman or Early Christian precedent. Cluny: huge and famous monastery in eastern France that spawned many branch houses. It was famous for its music, and also had a huge church with incipient buttressing of the upper walls (completed around 1130). Moissac, Abbey of St. Pierre: Cluniac monastery in southern France. Its South Portal (doorway) was adorned with relief sculpture c. 1120, including an expressively ascetic Prophet (probably Jeremiah) wound up the trumeau (central post on a doorway). He is joined there by lions. Above, in the tympanum , the Second Coming is depicted in an expressive fashion. The 7 figures here are flattened and abstract, but less so than in central France, and probably reflect some observation of ancient Roman sculpture. Autun Cathedral: the tympanum (lunette or half-circular arch over a door) of the West Portal was sculpted with a Last Judgement c. 1130 by a sculptor named Gislebertus. It includes a notable vision of Hell, with expressive demons weighing the souls of the dead. The great central Christ of the Second Coming is quite expressive, if very flat. The Morgan Madonna: an iconic wooden statue of the Virgin holding the Christ child, made c. 1150-1200. Its massive qualities and stylized drapery are typical Romanesque features. Wooden statues were often carried in parades on religious holidays. St. Savin-sur-Gartempe: a hall church in central France built ca. 1095-1115. Its barrel-vaulted nave preserves a notable fresco cycle of the Old and the New Testament in a schematic and rather childlike style (Tower of Babel, c. 1100), which is, however, easily "read." Christ in Majesty, Lerida: church at Santa Maria de Mur in northeastern Spain with a fresco in its apse (c. 1150). that is derived from Byzantine art (see, for example the apse of Monreale Cathedral, Sicily), but is flattened and stylized in the Mozarabic style that is based on Islamic art. Moralia in Job: an interpretation of the Book of Job in the Old Testement illuminated at a Cistercian monastery in France in the early 12th century. The Initial R page shows a knight (St. George) fighting two dragosn with the aid of his squire; the figures make up the letter R. Durham Cathedral: built in northern England 1093-1130, has groin-vaulted aisles. Its nave is groin-vaulted with ribbing, and is the immediate ancestor of Gothic churches. Also has interesting incised designs on its nave pillars. St. Etienne, Caen: begun in Normandy c. 1067-1100, its austerely powerful two-towered Westwork was built around 1100, and is the direct ancestor of Gothic facades. St. Etienne’s interior was groin-vaulted with ribbing (like Durham) in the 1120s; it was originally timber-roofed. Bury Bible: illuminated in England at Bury Saint Edmunds by Master Hugo c. 1135. It has a lively figural style, with abstracted color and interesting linear patterns on the drapery (Moses Expounds the Law) that are derived ultimately from Byzantine art, and lovely border motifs. The Bayeux Tapestry: actually embroidered, it depicts the story of the Norman conquest of England in 1066 with a wealth of narrative detail. Demonstrates the growing interest in secular (non-religious) themes in later Medieval art. The style very flat and two-dimensional, but lively (Battle of Hastings). Sewn ca. 1066-82. Mosan Metal Sculpture: the Meuse river region in Eastern Belgium and western Germany produced some of the finest Romanesque church furniture, notable for its Byzantine influenced naturalism. Famous works include the bronze baptismal font of renier of Huy (1107) and the silvere and bronze Reliquary for the skull of Pope Saint Alexander (c. 1145). Pisa Cathedral: part of an ensemble built 1053-1272, and which includes the famous Leaning Tower. The Cathedral (1063-1118 and later) has a facade with multiple stacked colonnades which remind one of ancient Roman facades (i.e. the Colosseum). The nave is timber roofed in imitation of the great Early Christian Basilicas of Rome (i.e. Old St. Peter's). The transept has a dome and the apse bears a Byzantinizing mosaic, both testimonies to Pisa's trade with the Byzantine Empire in this period. Wiligelmus: sculptor who made four lively panels depicting the Creation and Fall of Man (up to Noah) from the Book of Genesis around 1100. These were built into the façade of Modena Cathedral after 1106. The arcaded frame of Wiligelmus’ panels suggest that he was imitating Early Christian sculpted sarcophagi (see the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus), although his lumpy figures are scarcely very Roman. 8