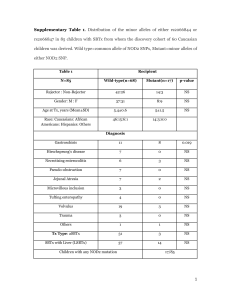

Outcast-Downey

advertisement