What Drives Canadian Corporate Dividend Policy: Agency Cost or

advertisement

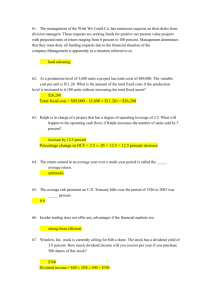

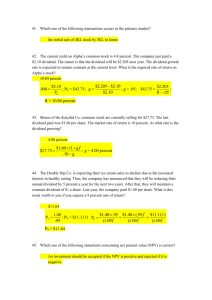

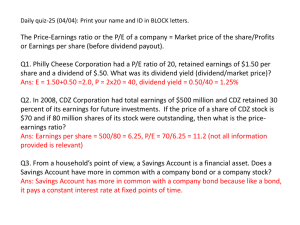

6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X What Drives Canadian Corporate Dividend Policy: Agency Cost or Information Asymmetry? Fodil Adjaoud, University of Ottawa, School of Management Imed Chkir, University of Ottawa, School of Management Samir Saadi *, University of Ottawa, School of Management Abstract We investigate the reaction of the Canadian market to dividend announcements in order to test the signaling theory against the agency cost theory. We also introduce the impact of the ownership structure of the companies on the information content of dividends. Our results show that dividend announcements are followed by significant abnormal stock returns: positive in case of dividend increases and negative in case of dividend decreases. A more detailed analysis of these abnormal returns shows that they are more important when the company is of small size and with the existence of blockholders. These results do not support the agency cost theory in explaining why do firms pay dividends and rather support the signaling theory. Introduction Despite a voluminous amount of theoretical and empirical studies over more than five decades, a lack of consensus among financial economists on why firms pay dividends still persists. In a perfect and frictionless capital market, when a firm’s investment policy is held constant, dividend policy is irrelevant because it has no effect on a firm’s stock price or its cost of capital (Miller and Modigliani, 1961). The highly restrictive assumptions of the irrelevance theory limit its application to real world situations. For instance, Black (1976) notes that given the classical tax rate preference for capital gains and deferral of capital gains taxation until the realization “corporation that pays no dividend will be more attractive to taxable individuals than a similar corporation that pays dividend.” Yet some companies offered large payouts (e.g. Lintner, 1956). This fact puzzled academia. For example, Brealey and Myers (2003) consider the dividend policy as one of the “10 unsolved problems in finance.” The dividend literature offers four standard theories to explain the dividend puzzle: signaling, tax preference and dividend clientele, agency, and bird-in-the-hand. Until recently, the signaling and agency theories have gained the most support. The tax clientele view has mixed results while the “bird-in-the-hand” explanation has received criticism from both empirical and theoretical views and has been labeled a “fallacy.” Studies supporting the signaling theory posit that a firm uses dividends as a device to convey private information about its future profitability; thus dividends lessen information asymmetry between management and shareholders and, in turn, enhance the firm’s value to shareholders (see among others, John and Williams, 1985; Bhattacharya, 1979; Miller and Rock, 1985). Hence, the signaling theory predicts a positive (negative) stock-price reaction to the announcement of dividend increases (decreases). This prediction is largely supported by empirical studies (Adjaoud, 1984; Healy and Palepu, 1988). More recent studies, however, stipulate that stock market reactions to dividend-change announcement are not due to a signaling role of dividends but rather to a reduction in agency costs within a dividend-paying firm. For instance, dividends can mitigate agency costs by forcing firms to seek funds from capital market, in which managers are subject to additional monitoring at lower cost (Easterbrook, 1984). Moreover, dividends payouts can reduce the likelihood of managers using excess returns to pursue their own interests and/or investing the firm’s free cash flows in sub-optimal projects (Jensen, 1986). Recently, some empirical studies cast serious doubt on the dividendsignaling hypothesis discussed above. For instance, Grullon, Michaely, Benartzi, and Thaler (2005) and Grullon, Michealy and Swaminathan (2002) show that dividend changes do not signal changes in firm’s future profitability. One would argues however, that if the signaling theory is deemed invalid then why managers are reluctant to cut dividends, and to increase them if firms cannot sustain such increases in the future? (see for instance, Lintner, 1956; Adjaoud, 1986; Baker, Saadi, Gandhi, and Dutta, 2006). * Corresponding author. saadi@management.uottawa.ca OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 1 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X The present study aims to address this luck of consensus in dividend literature on what explanation drives dividend policy by examining the stock price reactions to dividend announcements within the Canadian stock market. We conjecture that the recent preference toward the agency theory is due to omission of certain variables that if controlled for would uncover the signaling role of dividend pay-outs. While most of the literature predominantly focuses on the US stock market, we chose to examine the Canadian market as it presents a special case in the study of corporate dividend policy. First, ownership is highly concentrated in Canadian public firms but widely diffused in U.S. public firms. In Canada, a small group of large blockholders, or affiliated groups of investors, dominate the ownership scene, where wealthy families maintain some influence over public officials.1 Secondly, as Cheffins (1999) notes, Canadian public firms operate in a common law country and are subject to several legal recourses imposed by lawmakers to protect minority shareholders from corporate expropriation. The presence of high ownership concentration as in Canada is the norm rather than an exception around the world. While the mechanisms for protecting investors in countries with high ownership concentration have been questionable, minority shareholders in Canada receive the benefit of strong legal protection. Thirdly, Canadian equity market is less liquid that the US market where the average size of firms is much greater (Dutta, Jog, and Saadi 2005). Larger companies have more resources to distribute to their shareholders. In fact, White (1996) and Fama and French (2001) find that the probability of paying dividends increases with the size of the firm. Market liquidity may also influence a firm’s dividend payout decision. Lower liquidity leads to information asymmetry. In order to mitigate the adverse effect of information asymmetry, management might choose to pay higher dividends. Using a sample of Canadian firms that report dividend announcements between 1994 and 2000, we show that dividend announcements are followed by significant abnormal stock returns: positive in case of dividend increases and negative in case of dividend decreases. A more detailed analysis shows that these abnormal returns are more important when a company is of small size and are positively related to the existence of blockholders. These results do not support the agency cost theory explaining why do firms distribute dividends and rather support the signaling theory. The remaining of the paper is structured as follows. In Section II, we present a review of the literature on agency and signaling theories. Section III presents our research methodology. Section IV describes our data while Section V reports our empirical tests and results. Section VI concludes the paper. Literature Review In their seminal work, Miller and Modigliani (1961) show that, in a perfect and frictionless capital market, when a firm’s investment policy is held constant its dividend policy has no effect on shareholders wealth. Hence, shareholders should be indifferent between dividend payment and capital gains. However, contrary to this prediction and despite that dividends are usually more heavily taxed than capital gains, several firms follow extremely deliberate dividend payout strategies (Lintner, 1956). This fact perplexed financial economists for more than five decades. Black (1976) once remarked “The harder we look at the dividend picture, the more it seems like a puzzle, with pieces just don’t fit together.” Almost two decades later Baker, Powell, and Veit (2002) conclude, “Despite a voluminous amount of research, we still do not have all the answers to the dividend puzzle.” Endeavor to solve the “dividend puzzle”, the literature proposes several explanations. Of these, most empirical and theoretical studies favor two explanations usually seen as rival: The signaling theory and agency cost theory. Signaling theory Bhattacharya (1979), John and Williams (1985), and Miller and Rock (1985), among others, argue that dividends mitigate information asymmetry between management and shareholders. These theoretical models propose that dividend payments convey private information about a firm’s future profitability under the condition that a firm pays dividends on a regular basis. Several empirical studies strongly support the signaling explanation including Adjaoud, (1984), Asquith and Mullins (1983), and Lintner (1956). In particular, Lintner (1956) suggests that past dividends and current earnings determine current dividends. Asquith and Mullins (1983), and Healy and Palepu (1988) find a positive association between cash-dividend announcement and firm future profitability. Nissim and Ziv (2001) report a positive relationship between current dividend changes and future changes in profitability and earnings. Li and Zhao (2005) find that the propensity to pay or initiate dividends declines with the increase of analyst coverage. Amihud and Li 1 Morck, Stangeland, and Yeung (2000) report that 254 of the 500 largest Canadian companies represent privately held firms. The remaining 246 are public firms of which only 53 have broad ownership. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 2 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X (2006) find that the magnitude of stock price response to dividend changes has diminished since the mid-1970s, which could make firms less willing to incur costs associated with dividend signaling. Their evidence is consistent with the disappearing dividend phenomenon documented by Fama and French (2001) and should therefore be interpreted as supportive of dividend signaling theories. Other recent studies, however, cast doubt on signaling theory as being inconsistent with the “dividend disappearance” phenomenon. DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner (2004) posit that this shift in dividend payers is the result of a high concentration of dividends among a small number of firms with considerable earnings. Their evidence challenges the signaling theory as a first-order determinant of payout policy.2 Based on his analysis of six major international stock markets including the U.S., Osobov (2004) also rejects the signaling argument as an explanation for the shift of dividend payouts. Grullon, Michaely, and Swaminathan (2002) argue that dividends convey information about the degree of firm maturity and therefore signal the level of a firm’s risk rather than future cash flows. On the contrary to the results of Nissim and Ziv (2001), and Grullon et al. (2005) report a negative correlation between dividend changes and future changes in profitability, and show that models including dividend changes do not improve out-of-sample earning forecasts. Brav, Graham, Harvey, and Michaely (2005) find that U.S. managers strongly agree with the notion of dividend signaling but rarely use it consciously to separate their firms from the competition. Hence, they conclude that management views provide little support for the signaling hypothesis of payout policy. However, in a recent surveys of executives from Canadian firms listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX), Adjaoud and Zeghal (1998), and Baker, Saadi, Gandhi, and Dutta, (2006) find strong support for a signaling explanation for paying dividends, but not for the agency cost theory. Agency Theory The potential agency costs associated with the separation of management and ownership induce a conflictmitigation role for dividend payments. Jensen and Meckling (1976), Jensen (1986), and Lang and Litzenberger (1989) argue that dividends reduce the cash flow that managers have at their discretion. The agency theory stipulates that dividend payouts signal reduction in agency costs rather than future profitability. Several other empirical studies including Moh’d, Perry and Rimbey (1995) and Osobov (2004) show support for the agency explanation for dividends. For instance, Osobov (2004) argues “dividends disappearance” is consistent with the agency explanation given the recent improvements in international corporate governance. Easterbrook (1984) and Rozeff (1982) suggest that dividend payments force companies to go to equity markets in order to raise additional capital, thus reducing agency costs as a result of the increased scrutiny the capital market places on the firm. This gives outside shareholders the opportunity to exercise some control. Most of the literature on relation between dividends and agency costs employ Tobin’s Q, measured by the asset market-to-book ratio, as a proxy for the quality of a firm’s investment opportunity set and management’s inclination to invest in nonprofitable projects. Based on the signaling explanation, Tobin’s Q is an indication of investors’ expectation of a firm’s growth prospects or investment opportunities: A firm with a high Q ratio (i.e. Q>1) should exhibit higher abnormal returns following dividends announcement than a firm with low Q ratio (i.e. Q<1) since it is perceived by investors as having higher growth opportunities. Easterbrook (1984) and Rozeff (1982) use Tobin’s Q and find opposite results than those expected under signaling theory, which they interpret as evidence for dividend as an agency-cost-reducing mechanism rather than being a signaling tool. We contend that the results reported by Easterbrook (1984) and Rozeff (1982) are not necessarily inconsistent with the signaling explanation. Nevertheless, they could even be evidence for a signaling role of dividend policies if the above studies had controlled for the following factors: First, several studies find a positive association between Q ratio and firm size. For instance, Fama and French (1996), and Chan and Chen (1996) report that small firms display, in average, lower Q ratios than large firms. Secondly, others studies show that large firms are more widely covered by business press and followed by larger financial analysts than small firms. In fact, Atiase (1985) shows that the business press publish fewer items for small firms than for large firms. Based on Atiase’s (1980, 1985) differential information hypothesis, dividend announcements hold more surprise for small firms than large ones, thereby causing greater market reactions in terms of abnormal returns for small firms than for large firms. Freeman (1983) and Richardson (1984) report supporting evidence to the Atiase’s firm size hypothesis. If we take these two factors into consideration, reporting higher abnormal returns for firms with lower growth opportunities does not necessarily contradict the signaling explanation, but could back it since dividend announcements tend to exhibit more surprise for small firms. Accordingly, we would expect significantly higher stock-price reaction to dividend announcements for small firm compared to large ones. 2 Some may argue that the discussion in DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner (2004) based on the concentration of dividends among few large firms is qualitative and so insufficient to reject signaling theories. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 3 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X Research on dividend policy has taken an interesting twist since the publication of Fama and French (2001). Their evidence shows that in the past two decades the number and proportion of U.S. dividend-paying firms have dropped radically. Specifically, the proportion of dividend-paying firms fell from 67% to 21% between 1978 and 1999. Fama and French (2001) conclude that the drastic decline in dividend propensity over the last two decades is mainly due to changes in firm characteristics. They find that dividend-paying firms are those with high profitability and low growth, while non-paying firms tend to exhibit low profitability and high growth. Evidence by Grullon, Michealy and Swaminathan (2002) as well as DeAngelo and DeAngelo (2006) support this lifecycle-based explanation. This shows that, in the American context, dividend payout policies depend on three major factors namely profitability, size and growth opportunity. Two other important determinants of dividend policy which have received only limited attention until recently are ownership structure and shareholders legal protection. Several studies have introduced firm ownership structure to explain some aspect of the finance theory (Ang, Cole and Lin, 2000; Gugler and Yurtoglu, 2003a; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Morck, Shleifer and Vishny, 1988). Some studies shed light on the role of ownership structure in mitigating agency cost given its influential role in internal monitoring effort (Denis, Denis, and Sarin, 1997). Jensen and Meckling (1976), for instance, show that management stock ownership can reduce agency costs by aligning the interests of a firm's management with its shareholders. Ang, Cole, and Lin (2000) use asset turnover ratios to measure agency costs between managers and shareholders in closely held corporations, which the finance literature refers to vertical governance problem (Roe, 2004).3 They report significant inverse relation between agency cost and managerial shareholdings, thus providing a strong empirical support to theoretical work by Jensen and Meckling (1976). They also find that the agency cost increases with the number of non-managerial shareholders. More recent studies pay particular attention to the presence of blockholders and report that they have an important influence on monitoring firms. For example, Bhagat, Black, and Blair (2001) find that during the period 1987-1990 firms with large blockholdings exhibit superior performance than their peers. Several studies including Allen, Bernardo, and Welch (2000), Grinstein and Michaely (2003), Gugler and Yurtoglu (2003b), and Rozeff (1982), document an explicit relation between ownership structure and corporate dividend policy. For instance, Allen, Bernardo, and Welch (2000) and Grinstein and Michaely (2003) show that firm’s dividend decisions are related to the desirability of having institutional investors among their shareholders. 4 Amihud and Li (2006) partly attribute the decline in the information content of dividend announcements to the rise in stock ownership by institutional investors who are more sophisticated and informed. Rozeff (1982) reports a positive relation between dividend payout and the fraction of equity owned by managers and a negative relation with high dispersion of ownership measured by the number of stockholders of a firm. In the same vein, Noronha, Shome and Morgan (1996) find a positive relation between dividend payout ratio and the existence of blockholders. Recent studies further refine the dividend puzzle by providing evidence supporting the influence of shareholders legal protection on dividend decisions consistent with the agency theory (La Porta Lopez-De-Salinas, Shleifer, and Vishny 2000; Faccio, Lang, and Young 2001). For instance, La Porta et al. (2000) show that corporations operating in countries with strong legal protection of minority shareholders (i.e. common law countries) pay higher dividends than firms in countries with weak legal protection (i.e. civil law countries). They also find that high growth firms in common law countries pay lower dividends than low growth firms. This observation however was not reported for firms in civil law countries. Given the high ownership concentration of Canadian firms and the strong legal protection that minority shareholders benefit in Canada, we expect that the agency problem is not severe, and thus market reaction to dividends change should mainly reflect an information effect about firm’s future profitability. Research Methodology To examine shareholders reactions to dividend announcements, we use both univariate and multivariate analysis. The univariate analysis consists of an event study by which we aim to, first, examine stock price reaction to dividend announcements, and second, determine how this market reaction is affected by firm size and growth opportunity. Accordingly, at a first stage, we endeavor to test the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 1: Dividend announcements induce abnormal returns that are significantly different from zero. Hypothesis 2: Abnormal returns would be higher for firms with low growth opportunity (i.e. Q<1) than for firms with high growth opportunity (i.e. Q>1). 3 The second agency problem proposed by the finance literature is the governance problem between majority and minority shareholders labeled by Roe (2004) as horizontal governance problem. 4 Allen, Bernardo, and Welch (2000) argue that some firms prefer to be monitored by institutions in order to increase value. Given that institutions prefer dividends, these firms tend to attract them by paying higher dividends. Gillan and Starks (2000), and Hartzell and Starks (2003) report supporting evidence to the monitoring role of institutions. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 4 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X Hypothesis 3: Firms with Q<1 would be of small size, while those with Q>1 would be of large size. At a second stage, we employ a multivariate analysis where we seek to examine the influence of several variables on the informational content of dividend announcements. To examine stock price reaction to dividend announcements, we compute the abnormal returns using the Market Adjusted Model. The model defines abnormal returns as the excess return on a security, adjusted for the return on the market index over the same period of time. The equation for market adjusted abnormal returns is as follows: ARi ,t Ri ,t Rm ,t (1) Where: ARi ,t is the market adjusted abnormal return on security i over time t. Rm ,t is the time t return on the market index. Ri ,t is the time t return (including dividends) on security i. The literature of event study analysis proposes other models to estimate the abnormal returns, such as the Market Model. Nonetheless, several empirical studies show that Market Adjusted Model provides similar results to those of more sophisticated models (Brown and Warner, 1985). In addition the Market Adjusted Model has other advantages such as simplicity in implementation and interpretation. We measure the abnormal wealth effects by computing the average 10-day cumulative abnormal return across events: CARt 5 AARt 4 AARt ARi ,t N and where (2) N is the number of events. We compute and test for the statistical significance of the average cumulative abnormal return for dividend surprise in both directions: dividend increases of at least 10% and dividend decreases of at least 10%. The choice of the percentage change of 10% is consistent with recent empirical studies dealing with the information content of dividends changes (see, for example, Denis, Denis and Sarin, 1994; Yoon and Starks, 1995; and Lie, 2000). We use the following regression model to examine the determinants of market reactions to dividend announcements: CARi 0 1 SIZEi 2 GROWTH i 3 BlockHolde rsi 4 CFi i (3) Where: CAR SIZE GROWTH is the average cumulative abnormal return over (-1, +1) around the dividend announcements estimated using the Market Adjusted Model. We use a three-day window across announcement day following previous empirical studies such as of Yoon and Starks (1995). is the firm size measured by the natural logarithm of the market value of outstanding common stock. Based on Atiase’s (1980, 1985) differential information hypothesis, we expect the firm size’s coefficient to be negative since the informational content for small firm is greater than for large firms. is the growth opportunity measured by Tobin’s Q ratio (which is computed as market value of asset / book value of asset). We include Q ratio in our model in order to test for the dividend informational content hypothesis. If dividend announcements convey positive signal about firm future profitability, then we expect more positive stock price reactions, on average, for firms that have high growth opportunity than firms with low growth opportunity (Lang and Litzenberger, 1989). BlockHolders is an indicator of the level of ownership concentration and refers to the percentage of equity interest held as a group by the directors of the company and by other individuals or companies that own more than 10% of the equity shares of the company. Ang, Cole, and Lin (2000) report significant inverse relation between agency cost and managerial shareholdings. Rozeff (1982) reports a positive relation between dividend payout and the fraction of equity owned by managers and a negative relation with high dispersion of ownership measured by the number of stockholders of a firm. In the same vein, Noronha, Shome and Morgan (1996) find a positive relation between dividend payout ratio and the existence of blockholders. Given that Canada is a common low country where most of the firms are closely held agency problem between managers and shareholders should low, thus we expect the coefficient of “BlockHolders” OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 5 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics FC ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X variable to be negative.5 are the free operating cash flows. According to agency theory, dividends payouts lessen agency problems between corporate insiders and outside shareholders by reducing the amount of free cash flows that could be invested in unprofitable projects or diverted by insiders for personal use (Jensen, 1986; Lang and Litzenberger, 1989). Consequently, stock price reactions should increase with the level of free cash flow. Hence, we expect the coefficient of the free cash flow variable to be positive. Data Our initial sample includes all dividend-paying stocks listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) between January 1, 1994 and December 31, 2000. The dividend announcement dates are obtained from “Bloomberg” database. Our initial sample consists of 10,784 dividend announcement for 1,879 firms. For each announcement date we have its corresponding firm’s name, dividend type, record date, ex-dividend date and pay date. We exclude special dividends, dividend announcements by foreign corporations and dividends labeled in foreign currencies. Further, we use TSX Daily Record review to check for any major event relative to each firm within 10-day period across each announcement date. We eliminate observations where a major event is identified and deemed important enough to induce a contamination effect to the dividend announcement event. Our final sample consists of 2,130 announcements for the entire period. Their corresponding daily closing stock prices are obtained from the Canadian Financial Markets Research Centre Database CD (TSX-CFMRC). Data on stock prices are used to compute the daily returns and daily abnormal returns. Accounting data are provided in StockGuide database. To be consistent with previous studies dealing with dividend announcements and to ensure that potential signals announcements are significant, we classify the number of announcements in our sample as follows: Dividend increase: The percentage increase in dividends over the previous dividend should be at least 10%. Dividend decrease: The percentage decrease in dividends over the previous dividend should be at least 10%. Stable dividend: The percentage change in dividends over the previous dividend is less than 10%. Table 1 presents the partition of dividend announcements for each year by type dividend change. Two observations can be drawn about our sample. First, the number of dividend announcements increase over the period of study. Second, most of the announcements belong to the category of stable dividend, while there is much less dividend decreases than dividend increases. Insert Table 1 about here Empirical Results Table 2 reports abnormal returns and cumulative abnormal returns for 10 days across dividend announcement date. Some interesting observations emerge. First, announcements of dividend increase generate positive and significant abnormal returns. Indeed, the cumulative abnormal return for day -1 through day +1 is 1.26%. Second, when it comes to announcements of dividend decrease, however, the abnormal returns are negative and significantly different from zero. In fact, the cumulative abnormal return for day -1 through day +1 is -1.18%. Interestingly, results in Table 2 show no significant abnormal returns for announcement of stable dividends. Taken altogether, the results reported in Table 2 support hypothesis 1 showing that dividend announcements induce abnormal returns that are significantly different from zero: positive in the case of substantial dividend increase and negative in substantial dividend decrease. This has been said, however, the present results can be explained by either the signaling theory or agency theory. Therefore, further analyses are indeed necessary in order to identify what explanation drives the dividend policy in the Canadian stock market. Insert Table 2 about here Table 3 presents cross-sectional descriptive summaries between dividend announcement and the sign of the cumulative abnormal returns for day -1 through day +1. The results show that in the case of stable dividend, abnormal returns are equally distributed between positive returns (56.5%) and negative returns (43.5%). When dividends increase substantially, 79% of the abnormal returns are positive, while 81% are negative when dividends 5 It is noteworthy that the “BlockHolders” variable includes both inside blockholders (directors and managers) and outside blockholders (institutional and outside investors) ownership. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 6 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X decrease by at least 10%. The value of test of independence (χ 2 = 19.34) is significantly different from zero at 1% level, which supports the existence of strong association between abnormal returns and the type of dividend announcement. Insert Table 3 about here Results reported in Table 4 show that, in the case of dividend increase, the abnormal returns of day -1 to day +1 are significantly for firms with lower Q ratio, and inversely in the case of dividend decrease. For dividend decreases, the same pattern is observed: the abnormal returns for lower Q firms are lower than abnormal returns of higher Q firms. Based on t-test and z-test, the abnormal returns for the two groups of firms are significantly different. Though supporting hypothesis 2, these results may appear surprising if dividend changes are seen as signaling information about changes in future profitability. Based on this prediction, previous studies reject the signaling theory. However, and as stated in hypothesis 3, it is important to note that firms with low Tobin’s Q ratio are also of small size. In fact, as it can be observed from Table 4, there is reliable and strong evidence showing that the average size of firms with Q<1 is almost the half of the average size of firms with Q>1 and this for both dividend increase (ttest =-3.77) and dividend decrease (t-test = -3.13). If, as suggested by the differential information hypothesis, small firms are much less followed by financial analysts than large firms, then dividend announcements for small firm will cause greater market reactions in terms of abnormal returns. Consequently, further analyses are required before a conclusion could be reached on which of the two theories holds in explaining the Canadian corporate dividend policies. Insert Table 4 about here As suggested by Lie (2000), we use ordinary least squares regression to further examine the market reactions to dividend announcement. Table 5 presents the results of estimating model 3. The results show that there is reliable evidence of negative relation between firm size (SIZE) and abnormal returns across dividend announcement date (p-value 0.024). This provides supporting evidence to the differential information hypothesis, where dividend announcements for small firm cause greater market reactions than for large firms, as shown by Atiase (1985) and Li and Zhao(2005). The coefficient of the variable GROWTH is negative and significant at 1% level. This result corroborates the one reported in Table 4. As discussed above, based on results similar to ours, previous studies have rejected the signaling explanation in favor of agency cost theory. Moreover, our regression results show that there is reliable evidence of a positive association between level ownership concentration (BlockHolders) and abnormal returns (pvalue 0.032). This result is inconsistent with the view that dividend is a device that reduces agency costs between managers and shareholders (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Easterbrook, 1984; Rozeff, 1982). As stated above the variable “BlockHolders” includes both inside blockholders (directors and managers) and outside blockholders (institutional and outside investors) ownership. As Morck, Shleifer, and Vishny (1988), and Byrd, Parrino, and Pritch (1998) report, the impact of internal and external ownership on a firm’s decision-making process and performance could differ markedly. In other words, the preference of blockholders are not homogenous and as results the sign of the coefficient will be the net results of these competing preferences. Hence, the sign of the bockholders coefficient may reflect the nature of the influence of ownership structure in Canada on setting dividend policies. In fact, a positive sign shows that the resulting effect on corporate payout policies is a preference for dividends. Finally, the results reported in Table 5 suggest that the variable free cash flow (FC) has no significant influence on abnormal returns, which in turn present further evidence against the agency cost explanation. It noteworthy that our results are consistent with the survey results of Baker et al.(2006) where authors find that Canadian managers to express support for a signaling explanation for paying dividends, but not for the agency cost. Insert Table 5 about here Conclusion Black (1976) once remarked, “The harder we look at the dividend picture, the more it seems like a puzzle, with pieces just don’t fit together.” Attempting to solve this puzzle, the overwhelming volume of studies on dividend policy offer several explanations, where two of them have gained most of the support on the empirical ground: the signaling theory and agency cost theory. Recently, however, a growing number of studies, mainly in the U.S. context, report mixed results on what of the two theories explains the dividend policies. In an attempt to help solve this luck of consensus, we investigate the reaction of the Canadian market to dividend announcements, where firms exhibit a high level of ownership concentration and operate in environment where minority shareholders are highly protected. Our results show that dividend announcements are followed by OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 7 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X significant abnormal stock returns: positive in case of dividend increases and negative in case of dividend decreases. A more detailed analysis shows that the abnormal returns are greater when the company is of small size and with the existence of blockholders. These results do not support the agency cost theory in explaining why do firms pay dividends and rather support the signaling theory. Based on the above results, it will be interesting to test, in subsequent years, whether a firm future profitability is consistent with its corresponding signals conveyed by dividend announcements. Another avenue for future research is to replicate the present study in countries with different legal protection and ownership concentration than in Canada, and see how these factors would affect our results. Moreoever, since the coefficient of the variable “BlockHolders” reflects the resulting preference of different type of blockholders, future research can also look at the effect of each type of blockholders: outside block holders and inside blockholders for both dividend announcement increases and decreases. A particular attention should also be paid to the presence of institutional blockholders. This would provide a better understanding of the stock market reaction to dividend announcements. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 8 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X References Adjaoud, F., and Zeghal, D., (1998) “Management views on dividend policy: A survey of Canadian firms’’, International Review of Accounting, Vol 3, pp. 57-71. Adjaoud, F., (1986) “The Reluctance to Cut Dividends : A Canadian Case”, Finance, Vol 7, pp. 169-181. Adjaoud, F., (1984) “The Information content of dividends: A Canadian test”, Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, Vol 1, pp. 338-351. Allen, F., Bernardo, A.E., and Welch, I., (2000) “A theory of dividends based on tax clienteles”, Journal of Finance, Vol 55, pp. 2499-2536. Amihud, Y., and Li, K., (2006) “The declining information content of dividend announcements and the effect of institutional holdings”, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis (forthcoming). Ang, J.S., Cole, R.A., and Wuh L.J., (2000) “Agency costs and ownership structure”, The Journal of Finance, Vol 55, pp. 81-106. Asquith, P., and Mullins, D., (1983) “The impact of initiating dividend payments on shareholders wealth”, Journal of Business, Vol 56, pp. 77-96. Atiase, R.K., (1980) “Predisclosure informational asymmetries, firm capitalization, earnings reports, and security price behavior around earnings announcement.” Unpublished Ph.D dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. Atiase, R.K. (1985) “Predisclosure information, firm capitalization and security price behavior around earnings announcements”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol 23, pp. 21-36. Baker, H.K., Saadi, S., Gandhi, D., and Dutta, S., (2006) “How Canadian managers view dividend policy: New survey evidence”, Proceeding of forthcoming 55th Annual Meeting of the Midwest Finance Association, March 23-25, Chicago, Illinois. Baker, H.K., Powell, G.E., and Veit, E.T., (2002) “Revisiting the dividend puzzle: Do all of the pieces now fit?”, Review of Financial Economics, Vol 11, pp.241-261. Bhagat, S., Black, B., and Blair, M., (2001) “Relational investing and firm performance”, Working paper, Stanford University, Stanford, California. Bhattacharya, S., (1979) “Imperfect information, dividend policy and the bird in the hand fallacy”, Bell Journal of Economics, Vol 10, pp. 259-270 Black, F., (1976) “The dividend puzzle”, Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol 2, pp.5-8. Brav, A., Graham, J.R., Harvey, C.R., and Michaely, R., (2005) “Payout policy in the 21 st century”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 77, pp. 483-527. Brealey, R. A., and Myers, S. C., (2003), Principles of Corporate Finance, McGraw Hill, New York. Brown, S., and Warner, J., (1985) “Using daily stock returns: The case of event studies”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 14, pp. 3.31. Byrd, J., Parrino, R., and Pritch, G., (1998) “Stockholder-manager conflicts and firm value”, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol 54, pp. 14-30. Chan, K.C., and Chen, N., (1991) “Structural and return characteristics of small and large firms”, The Journal of Finance, Vol 46, pp.529-554. Cheffins, B., (1999) “Current trends in corporate governance: Going from London to Milan via Toronto”, Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law, Vol 10, pp. 5-42. DeAngelo, H., and DeAngelo, L., (2006) “The irrelevance of the MM dividend irrelevance theorem”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 97, pp. 293-315. DeAngelo, H., DeAngelo, L., and Skinner, D.J., (2004) “Are dividends disappearing? Dividend concentration and the consolidation of earnings”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 22, pp. 425-456. Denis, D.J., Denis, D.K., and Sarin, A., (1997) “Ownership structure and top executive turnover”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 45, pp. 193-221. Dutta, S., Jog, V., and Saadi, S., (2005) “Re-examination of the ex-dividend day behavior of Canadian stock Prices” 2005 European Financial Management Association meetings, Milan, Italy. Easterbrook, F.H., (1984) “Two agency costs explanations of dividends”, American Economic Review, Vol 74, pp. 650-659. Faccio, M., Lang, L.H.P., and Young, L., (2001) “Dividends and expropriation”, American Economic Review, Vol 91, pp. 54–78. Fama, E.F., and French, K.R., (2001) “Disappearing dividends: Changing firm characteristics or lower propensity to pay?”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 60, pp. 3-43. Fama, E., French, K., (1996) “Multifactor explanations of asset pricing anomalies”, Journal of Finance, Vol 51, pp. 55-84. Freeman, R.N., (1983) “Alternative measures of profit margin: An empirical study of the potential information content of current cost accounting”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol 21, pp. 42-64. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 9 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X Gillan, S.L., Starks, L.T., (2000) “Corporate governance proposals and shareholder activism: The role of institutional investors”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 57, pp. 275–305. Grinstein, Y., and Michaely, R., (2003) “Institutional holdings and payout policy”, Journal of Finance, Vol 60, pp. 1389-1426. Grullon, G., Michaely, R., and Swaminathan, B., (2002) “Are dividend changes a sign of firm maturity?”, Journal of Business, Vol 75, pp.387-424. Grullon, G., Michaely, R., Benartizi, S., and Thaler, R., (2005) “Dividend changes do not signal changes in future profitability”, Journal of Business, Vol 78, pp. 1659-1682. Gugler, K., and Yurtoglu, B., (2003a) “Average Q, marginal Q and the relation between ownership and performance”, Economics Letters, Vol 78, pp. 379-84. Gugler, K., and Yurtoglu, B., (2003b) “Corporate governance and dividend pay-out policy in Germany”, European Economic Review, Vol 47, pp. 731-758. Hartzell, J., and Starks, L., (2003) “Institutional investors and executive compensation”, Journal of Finance, Vol 58, pp. 2351-2375. Healy, P., and Palepu, K.G., (1988) “Earnings information conveyed by dividend initiations and omissions”, Journal of financial Economics, Vol 21, pp. 149-176. Jensen, M.C., (1986) “Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers”, American Economic Review, Vol 76, pp. 323-329. Jensen, M.C., and Meckling, W.H., (1976) “Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 3, pp. 305-360. John, K., and Williams, J., (1985) “Dividends, dilution, and taxes: A signaling equilibrium”, Journal of Finance, Vol 40, pp. 1053-1070. Lang, L.H.P., and Litzenberger, R.H., (1989) “Dividend announcements: Cash flow signaling vs. free Cash flow hypothesis”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 24, pp. 181-191. La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Salinas, F., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R., (2000) “Agency problems and dividend policy around the world”, Journal of Finance, Vol 55, pp. 1-33. Li, K., and Zhao, X., (2005) “Dividend policy: The role of analyst coverage”, University of British Columbia, Working Paper. Lie, E., (2000) “Excess funds and agency problems: An empirical study of incremental cash disbursements”, Review of Financial Studies, Vol 13, pp. 219-247. Lintner, J., (1956) “Distribution of incomes of corporations among dividends, retained earnings and taxes”, American Economics Review, Vol 46, pp. 97-113. Miller, M. H., and Modigliani, F., (1961) “Dividend policy, growth, and the valuation of shares”, Journal of Business, Vol 34, pp. 411-433. Miller, M., and Rock, K., (1985) “Dividend policy under asymmetric information”, Journal of Finance, Vol 40, pp. 1031-1051. Moh'd, M.A., Perry, L.G., and Rimbey, J.N., (1995) “An investigation of dynamic relationship between agency theory and dividend policy”, Financial Review, Vol 30, pp. 367-385. Morck, R., Stangeland, D. A., and Yeung, B., (2000) “Inherited wealth, corporate control, and economic growth: The Canadian disease”, in Morck, R. (ED.), Concentrated Corporate Ownership, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, pp.319-369. Morck, R., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R., (1988) “Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 20, pp. 293-351. Nissim, D., and Ziv, A., (2001) “Dividend changes and future profitability”, Journal of Finance, Vol 56, pp. 21112133. Noronha, G.M., Shome, D.K., and Morgan, G.E., (1996) “Monitoring rationale for dividends and the interaction of capital structure and dividend decisions”, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol 20, pp. 439–454. Osobov, I., (2004) “Why are dividends disappearing: An international comparison”, 2004 FMA Annual Meeting, New Orleans, Los Angels. Richardson, G., (1984) “The information content of annual earnings for large and small firms: Further empirical evidence”, Working paper, University of British Columbia. Roe, M., (2004) “The institutions of corporate governance” Working Paper, Harvard Law School, Cambridge, MA. Rozeff, M.S., (1982) “Growth, beta and agency costs as determinants of dividend payout ratios”, Journal of Financial Research, Vol 5, pp. 249-259. Yoon, P.S., and Starks, L., (1995), “Signaling, investment opportunities, and dividend announcements,” Review of Financial Studies, Vol 8, pp. 995-1018. White, L. F., (1996) “Executive compensation and dividend policy”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol 2, pp. 335358. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 10 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X Table 1: Sample Partition by Year and by Type of Dividend Change for Firms listed on Toronto Stock Exchange over the Period 1994-2000. Table 1 presents a classification of the number of announcements in our sample by year and by type of dividend changes: Dividend increase: The percentage increase in dividends over the previous dividend should be at least 10%. Dividend decrease: The percentage decrease in dividends over the previous dividend should be at least 10%. Stable dividend: The percentage change in dividends over the previous dividend is less than 10%. The announcement date (day 0) is the dividend declaration date, provided in “Bloomberg”. 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Total Dividend Increase 56 54 64 72 137 149 104 636 Stable Dividend 124 162 164 188 46 99 290 1073 Dividend Decrease 19 25 28 33 121 159 36 421 Total 199 241 256 293 304 407 430 2130 Table 2: Abnormal Returns & Cumulative Abnormal Returns Table 2 reports the average abnormal returns (AAR) and average cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) for day -5 through day 4, for each of the three dividend change categories: Dividend increase: The percentage increase in dividends over the previous dividend should be at least 10%. Dividend decrease: The percentage decrease in dividends over the previous dividend should be at least 10%. Stable dividend: The percentage change in dividends over the previous dividend is less than 10%. The announcement date (day 0) is the dividend declaration date, provided in “Bloomberg”. Abnormal returns are computed using the Market Adjusted Model. Dividend Increase Stable Dividend Dividend Decrease (N = 636) Day (t) AAR CAR (%) (%) (N = 1073) t-test AAR CAR (%) (%) (N = 421) t-test AAR CAR (%) (%) t-test -5 0.11 0.11 0.46 0.005 0.005 0.01 0.03 0.03 0.49 -4 0.16 0.27 0.98 0.01 0.01 0.05 -0.24 -0.20 -1.05 -3 0.16 0.43 1.02 0.16 0.17 0.89 -0.19 -0.40 -1.58 -2 0.25 0.67 1.08 0.06 0.23 0.28 -0.02 -0.42 -1.61 -1 0.37 1.04 2.21** -0.02 0.21 -0.09 -0.32 -0.73 -1.92** 0 0.46 1.50 2.67*** -0.04 0.17 -0.21 -0.51 -1.24 -2.44*** 1 0.43 1.93 2.15** 0.05 0.22 0.29 -0.35 -1.59 -1.94** 2 0.36 2.29 1.59 -0.05 0.17 -0.27 -0.52 -2.11 -1.98** 3 0.30 2.59 1.20 -0.16 0.01 -0.91 -0.31 -2.42 -1.07 4 0.21 2.80 1.13 0.33 0.34 1.18 -0.08 -2.50 -0.86 *** Significant at 1%; ** Significant at 5%; * Significant at 10 %. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 11 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X Table 3: Test of Independence Table 3 presents cross-sectional descriptive summaries between dividend announcement and the sign of the cumulative abnormal returns for day -1 through day +1. Figures in parentheses are t-statistics. The announcement date (day 0) is the dividend declaration date, provided in “Bloomberg”. Dividend Announcement Type Positive Cumulative Abnormal Return Increase Stable Decrease Negative Cumulative Abnormal Return Total 502 (79%) 134 (21%) 636 606 (56.5%) 467 (43.5%) 1073 80 (19%) 341 (81%) 421 1 188 942 2 130 Total χ = 19.34, significant at 1%. 2 Table 4: Rank by Tobin’s Q Ratio Panel A. Dividend Increase The present table presents descriptive statistics for dividend increase. N is the number of observation, Q is market value of assets / book value of assets. AAR0 is the average abnormal returns on the dividend announcement day. Q<1 Q≥1 t-test z-test (N = 234) (N = 148) Tobin’s Q ratio 0.48 2.10 -11.54*** AAR -1 0.38 0.24 1.65** -1.72** AAR0 0.47 0.25 1.83** -1.78** AAR1 0.59 0.31 2.04** -1.83** 10,900 26,644 -3.77*** -6.22*** Total Asset (in M$) -16.36*** Panel B. Dividend Decrease The present table presents descriptive statistics for dividend increase. N is the number of observation, Q is market value of assets / book value of assets. AAR0 is the average abnormal returns on the dividend announcement day. Q<1 Q≥1 t-test z-test (N = 199) (N = 103) Tobin’s Q ratio 0.47 2.05 -9.11*** -14.24*** AAR -1 -0.33 -0.21 -1.42* -1.69** AAR0 -0.78 -0.49 -2.09** -3.31*** AAR1 -0.57 -0.47 -1.34* -1.62** 19,534 32,751 -3.13*** -4.17*** Total Asset (in M$) *** Significant at 1%; ** Significant at 5%; * Significant at 10 %. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 12 6th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 0-9742114-6-X Table 5: Multivariate Analysis Table 5 present the results of estimating the following model: CARi 0 1 SIZE i 2 GROWTH i 3 BlockHolders i 4 FCi i ; where CAR is the cumulative abnormal return over (-1, +1) around the dividend announcements estimated using the Market Adjusted Model, SIZE is the firm size measured by the natural logarithm of the market value of outstanding common stock., GROWTH is the growth opportunity measured as market value of asset / book value of asset, BlockHolders is an indicator of the level of ownership concentration and refers to the percentage of equity interest held as a group by the directors of the company and by other individuals or companies that own more than 10% of the equity shares of the company, FC are the free operating cash flows. Coefficient t-test p-value Intercept SIZE GROWTH BlockHolders FC 0.0634 -0.0033 -0.003 0.01 0.0001 3.0972*** -2.2572** -2.8703*** 2.1482** 0.4632 0.002 0.024 0.0042 0.032 0.30 *** Significant at 1%; ** Significant at 5%; * Significant at 10 %. OCTOBER 15-17, 2006 GUTMAN CONFERENCE CENTER, USA 13